Cult Conversations: Interview with Caetlin Benson-Allott (Part II)

/There are a lot of claims in press discourse about a new Golden Age of horror cinema. What are your thoughts about this? Do you think there is truth to these claims? Or is this journalistic hyperbole?

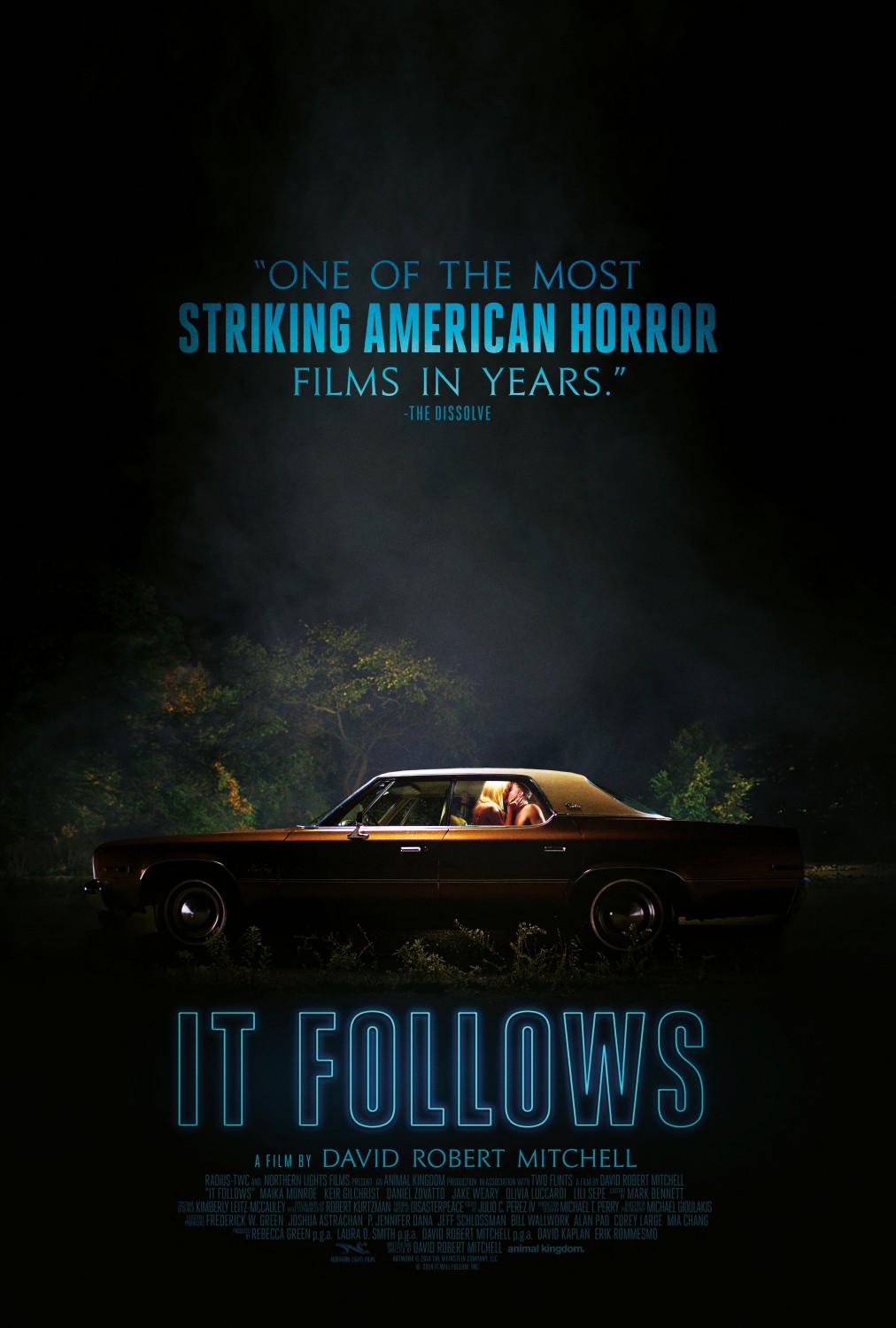

The past few years have seen an amazing spate of new releases that engage conventions of the horror genre while also challenging some of its conventional shock techniques choices and more obvious clichés. Two of my favorites have been Trey Edward Shults’s It Comes at Night (2017), David Robert Mitchell’s It Follows (2014), and Patrick Brice’s Creep (2014) and Creep 2 (2017). What makes these films exceptional to me is their investment in character, something I think we’re seeing a lot more of in horror at the moment. Not that there aren’t precedents for character-driven, psychologically credible horror movies in the past—Roman Polanski’s Apartment Trilogy comes to mind, not to mention Tomas Alfredson’s Let the Right One In (2008)—but horror does always not require well-rounded or realistic characters to work well. (I love Night of the Living Dead and Texas Chain Saw Massacre [Tobe Hooper, 1974] but their strengths are not in their characters.)

The one thing that troubles me about the journalism on this Golden Age, however, is how focused it has been on English-language horror film. Many of the films being celebrated now borrow extensively from international horror traditions, many of which have a closer relationship to melodrama than Anglophone horror movies. So when people tell me they loved It Follows, I point them to Julia Docournau’s Grave (Raw, 2016). We’re in a fantastic multinational Golden Age of horror.

There have also been claims made about the surfacing of new generic characteristics in horror, one of which is centred on this notion of the ‘post-horror film.’ Is this legitimately “a new breed of horror,” do you think?

No, I don’t think so. We’re seeing American horror filmmakers deviate from their national tradition, with its jump scares, high body counts, and spectacular special effects. But if one thinks internationally and historically, there are many precedents for “post-horror.” Schults cites some excellent ones in the Guardian article you link to. I also think it’s important to note the influence of Japanese and Korean horror on Western genre directors of late. While Japanese horror certainly has not shied away from onscreen violence and gore, it also boasts a much more nuanced understanding of horror as an affect than the US tradition.

Going back to Psycho and even the Universal horror classics, American horror has been more invested in frightening, shocking, and even disgusting its audience than in horrifying them. The philosopher Robert C. Solomon defines horror as a profound “recognition that things are not as they ought to be.” As I have written elsewhere, “Truly horrible things don’t frighten; they don’t make people yelp or clutch the arms of their chairs in surprise. They don’t elicit nervous giggling or merry catcalls. Rather they paralyze and dumbfound as people struggle to understand how something so unthinkable, so beyond any expectations, could come to pass.” Moves like It Comes at Night or The Witch (Robert Eggers, 2015) may not be trying to frighten their viewers at all but rather to horrify them, to destabilize their precious beliefs about how families operate. But what horrifies one person will not necessarily horrify another. It’s a lot easier to prey on viewers’ reflexes with a jump scare than prompt them to question deeply cherished beliefs.

The rise of Blumhouse and the so-called ‘micro-budget’ horror film is often viewed in entertainment news as a major economic shift. Beginning with Paranormal Activity in 2007—a film that holds the box office record for the largest return-on-investment in film history—a ‘cycle’ which includes multiple examples of what you have described as “faux footage horror films” (Unfriended, The Bay, etc.) seems to have emerged. Conceptually, do you see the ‘microbudget’ commercial model as different than exploitation or low-budget economic models historically? Is there a difference between ‘micro-budget’—which for Blumhouse means up to $5 million, and at times, even higher—and “low-budget,” or “b-movie”? Considering that horror cinema has often been at the lower end of the economic scale, what do you think has precipitated these shifts in budget (if indeed there are noticeable shifts)?

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre and The Blair Witch Project (Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez, 1999) provide interesting context for considering this question. Released in 1974 by Bryanston Pictures—the same company that released Deep Throat two years earlier—The Texas Chain Saw Massacre was absolutely received as an exploitation film. Its opening crawl also (falsely) identified it as the true story of “one of the most bizarre crimes in the annals of American history.” Limited funds pushed director Tobe Hooper towards many of the creative decisions that make the film so horrifying and so powerful. And now it’s part of the permanent collection at New York’s Museum of Modern Art.

The Blair Witch Project isn’t in MOMA (yet), but it too used budgetary constraints as a structuring device and advanced “faux footage” as a horror filmmaking technique. It too claims to be a “true story” in in its opening title card. But it was released twenty-five years after The Texas Chain Saw Massacre and was received as an example of “indie” genre filmmaking rather than exploitation filmmaking. It premiered at Sundance, after all, before Artisan gave it a slow roll-out to build the word-of-mouth enthusiasm that made it a sleeper hit.

So, no, I don’t think micro-budget filmmaking is new to the horror, although the way in which horror directors have approached low-budget independent production is certainly different than the means employed by Hollywood’s Poverty Row studios in the 1930s and 1940s and for the various sub-genres of exploitation cinema popular in the 1960s and 1970s. Whether we’re thinking about The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, The Blair Witch Project, Night of the Living Dead, The Last House on the Left (Wes Craven, 1972), or direct-to-video horror like Blood Cult (Christopher Lewis, 1985), we can see how the distributive possibilities of an era governed filmmakers’ approaches to limited budgets. Blumhouse and the faux footage horror movies are two responses to making scary movies with limited means that found traction in their era. But I do wonder whether we should consider Blumhouse movies “microbudget.” Night of the Living Dead was made for $114,000 in 1968—which would be less than $850,000 in 2018. The Blair Witch Project was made for $60,000 in 1997, which would only be $95,000 today. Granted, these figures don’t include marketing or print costs, but they still afford their filmmakers very different opportunities than those available to folks working for Blumhouse.

In Killer Tapes, you argue that Paranormal Activity—and by extension other ‘faux footage films’—“teach the spectator not to go searching for underground videos, because what she finds could be deadly” (168). Could you expound on this point? Is this a theoretical argument? Or do you believe that such films have value for studios as a way to caution viewers not to illegally download material—not because it is against the law, but because they may end up haunted or demonically possessed?

In the chapter you cite, “Paranormal Spectatorship,” I note that the “faux footage” horror film cycle emerged contemporaneously with the rise of peer-to-peer file sharing of feature motion pictures. In 2004, MPAA president Dan Glickman argued that to win the war on piracy, “we have to find new product.” I found this quote really mysterious and compelling. What “product” was Glickman referring to? The movies themselves? Could one read a cycle of horror films as expressing filmmakers’ and studios’ anxieties about piracy and a new, albeit illicit, distribution platform for motion pictures? In every faux footage horror movie up until 2013, when Killer Tapes and Shattered Screens was published, all of the characters die; their footage reaches the spectator posthumously. The position we watch from then is that of a ghoul, someone who consumes the dead. These movies are titillating precisely because they seem illicit, because they give us the feeling tha we should not be watching them. Historicizing that affect and its appeal, I found it related to contemporaneous anxieties about online piracy in the US film industry. That’s not to say that I think Oren Peli (the director of Paranormal Activity) or Matt Reeves (the director of Cloverfield) sat down and thought, “I’d like to make a film that will discourage viewers from pirating movies online.” I’m not interested in guessing at their intentions. But I do think that faux footage horror found purchase as a film cycle because of cultural and industry anxieties about illicit spectatorship at that point in time.

So, yes, mine is a theoretical argument, but it’s also a historically specific argument. I would not make the same argument about “screenlife” or “screencast” movies like Unfriended or Searching. Those films tell very different cautionary tales about online sociality, privacy, and mortality in the age of social media.

Expounding on that point, what kinds of cautionary tales do you think these ‘social media horror’ films are producing? These kinds of films seem to be gathering pace—alongside Unfriended and Searching, there has also been Friend Request, The Den (2013), Scare Campaign (2016), Like Me (2017), and, more recently, a sequel to Unfriended (subtitled Dark Web). What do you think of these kinds of films and what do they purport to caution against?

I think that screencast horror films tend to express an anxiety about the effects of online sociality and information cultures on human subjectivity. Shane Denson has done some amazing work on Unfriended and what he calls “the horror of discorrelation,” focusing on the phenomenological differences between computational processing time and our human experience of time. I would add that the question of what constitutes a friend and where one constitutes “real” identity, through interpersonal interactions or online, are also major preoccupations of these films.

One of the things I found very interesting about Unfriended was the way in which its plot mimicked a classic American slasher movie—a number of unlikeable characters are introduced early on and then killed off one at a time as the killer’s intentions become clearer. In that context, it becomes quite important that Laura, the monster, also possesses many characteristics of the classic Final Girl (as theorized by Carol Clover in Men, Women, and Chainsaws).

What are you currently working on and what plans do you have for future projects?

Right now, I am working on a book manuscript that argues that our materially and socially grounded interactions with film and television inform the political impact of those texts as much as the texts themselves. Like all my work, the new book focuses on uniting texts and paratexts towards deeper understandings of media culture. In this case, however, I am turning from spectatorship to reception, and particularly to the material realities of media reception, in order to argue that we read media with and through objects. These objects range from media platforms like VHS and DVD to inebriants like alcohol and marijuana as well as objects that are brought into into scenes of reception by viewers and distributors, such as guns and branded merchandise.

Focusing on the gun, for instance, I argue that the history of violent assaults at movie theaters—cinema violence—reveals much about the racist, neoliberal fantasy undergirding popular conception of cinema and cinemagoers in the US. This history has not been collected before, however, and so I chronicle the long list of shootings, stabbings, riots, and other violent incidents at movie theaters from the anti-racist protests at D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (1915) through the non-fatal shooting at 13 Hours: The Secret Soldiers of Benghazi in 2016. Since the 1970s, anti-Black racism and white privilege have shaped media representations of cinema violence. Cinema violence is always tragic, but not all cinema violence is treated as tragic, due to racialized fantasies undergirding past and present notions about who does and does not belong in movie theaters. (Early extracts from this chapter were published as a column in FLOW, beginning with “‘Warriors, Come Out to Play’: Considering The Role Of Films In Moral Panics About Cinema Violence.”

Horror is not an explicit part of this new book project, but I continue to write about horror in articles and in my column for Film Quarterly.

What five films would you recommend that you feel represents ‘the best’ that horror or cult cinema can offer and why?

I’m choosing five films to reflect the different strengths of the horror genre and of horror as a filmic affect. The distinction between horror as genre and affect directs my current interest in scary movies and their criticism. Many critics have written about horror as a genre uniquely tied to the affect it aims to generate, but I would contend that very few so-called horror movies actually want to horrify the viewers. If we defined horror as a profound destabilization of one’s perception of the world, then most horror movies do not try to do that. They try to scare, startle, shock disgust, and even mortify. They might make one feel fear, dread, or anxiety, but do they really want to undermine a viewer’s beliefs in universe or in human nature? I would submit not. I don’t see Friday the 13th (Sean S. Cunningham, 1980) or The Thing (John Carpenter, 1982) attempting to “rattle my cage” on such a deep level—which is not to say that some people may not be truly horrified by those movies. What horrifies one person may barely phase another.

Night of the Living Dead (George A. Romero, 1968)

This is just simply my favorite movie. If you enjoy it too, then I strongly recommend Ben Hervey’s excellent book on its production, reception, and distribution. The Image Ten collective was an incredibly canny group of filmmakers who exploited the strengths of their industrial conditions and their projects exhibition platform (namely drive-in theaters) to craft a film that reflected and developed social anxieties of the era. That the zombie would prove such a capacious metaphor for alienation and disenfranchisement could not have been predicted, but Romero and company modelled the horrifying capacities of monster-as-social-metaphor for a generation of filmmakers.

Ich seh, Ich she (Goodnight, Mommy, Veronica Franz and Severin Fiala, 2014)

Franz and Fiala’s film horrified me more than any other I’ve seen. I don’t want to say too much about it, as I knew next to nothing about it when I took a friend to a matinée screening one Saturday morning. But its riveting engagement with psychic and physical abjection was almost more than I could take.

(Proctor heads off immediately to purchase film).

Get Out (Jordan Peele, 2017)

As I’ve mentioned, not all horror movies aim to horrify or aim to scare viewers in the same way. This one does, but it does so by violating the rules of the horror genre. Get Out cites the conventions of US horror but does not always perform them, which has led some genre fans to complain that it is not really a horror movie. To say that is to a great disservice to the film and to the genre. Get Out is horrifying, especially if you encounter it, as Jordan Peele has suggested, as a documentary about contemporary US racism. There are precious few explicitly anti-racist horror movies yet the horrors of racism remain one of the dominant structures of feeling in the US today.

La Casa Muda (The Silent House, Gustavo Hernández, 2010)

Ignore the American remake. Hernández’s La Casa Muda was not shot in a single take, and yet, like Hitchcock’s Rope (1948), it is carefully edited to appear to be a single-take film. What’s interesting about this conceit in this movie, though, is that the plot focuses on a trauma survivor recovering memories of abuse. By presenting the process of recollection in real time, the film offers its viewer a unique experience of trauma, of the temporality of horror.

The Slumber Party Massacre (Amy Holden Jones, 1982)

Not all ‘80s slasher movies were created equal. Feminist novelist, activist, and screenwriter Rita Mae Brown developed The Slumber Party Massacre as a pro-woman parody of slasher movies. Director Amy Holden Jones stays true to this vision while also providing enough of titillating gore to satisfy her distributor, New World Pictures. The result is in some sense a compromise picture, but it’s also an historically important example of women’s work in the horror genre, all the more so because so many critics interpreted it at the time as a “straight” slasher movie. And it’s really funny (at least to me).

Caetlin Benson-Allott is Provost’s Distinguished Associate Professor of English and Film and Media Studies at Georgetown University and the Editor of JCMS (formerly Cinema Journal). She is the author of Killer Tapes and Shattered Screens: Video Spectatorship from VHS to File Sharing (2013) and Remote Control (2015). Her work on US film cultures, exhibition history and material culture, spectatorship theory, and gender and sexuality studies has appeared in Cinema Journal, The Atlantic, South Atlantic Quarterly, Journal of Visual Culture, Jump Cut, Film Quarterly, Film Criticism, Feminist Media Histories, In Media Res, FLOW, and multiple anthologies. She is a regular columnist and Contributing Editor at Film Quarterly.