Cult Conversations: Interview with Xavier Aldana Reyes (Part I)

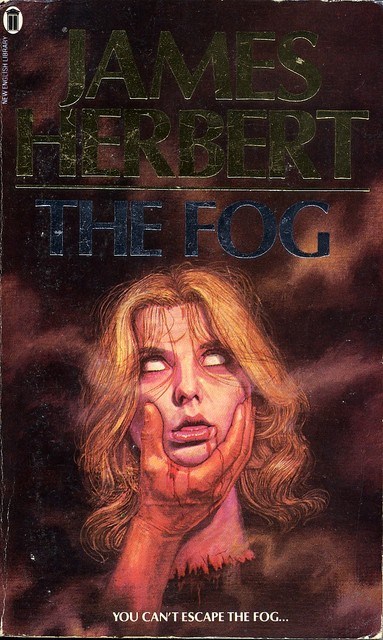

/I often joke that I was taught to read not by teacher or parent, but by the many novelists that were active during the horror fiction boom of the 1970s and 80s: Gary Brandner, Graham Masterton, Ramsey Campbell, Claire McNally, Guy N. Smith—and of course, James Herbert and Stephen King. I fell hard for Herbert first of all, mainly because my dad usually returned home from work with a battered paperback in hands, a gruesome image of some kind displayed on the cover, images that publishers certainly wouldn’t get away with these days. This was the era of the so-called ‘video nasties’ controversy led by Margaret Thatcher’s Tory government along with moral campaigner du jour Mary Whitehouse. But no one seemed to be concerned that many teens in the 1980s were delving deeply into the dark recesses of literary horror. Indeed, video was the main political target, eventually leading to the formation of the Video Recordings Act in 1984. But horror fiction was largely left alone by the government, despite those grotesque paperback covers that have all but disappeared from the shelves, or been ‘tastefully’ gentrified for the polite high street book store. Even books that are continually reprinted today—Herbert and King being dominant—no longer include these transgressive, marvellously lurid covers (see the different covers for Herbert’s The Fog below). That said, Grady Hendrix’s excellent compendium, Paperbacks from Hell, is a must-buy for fans of horror fiction, and at least offers a historical record for posterity’s sake. (I have tried to seek some of these out on the internet, but, alas, like many fan objects, they fetch a hefty price.)

I guess I wouldn’t be permitted to read these novels if I was a child today, not that that would have stopped us. I wasn’t allowed to listen to N.W.A’s ‘Fuck the Police’ or the 2Live Crew’s ‘As Nasty as They Wanna be’ either; but the more that cultural objects are deemed forbidden by our moral guardians, be it parent, teacher or government, the more we want to explore, discover and transgress authoritative boundaries. James Herbert gave us pornography when it wasn’t readily available (although we always found that too, snuggled deep in socks and underwear). I knew there was something forbidden about reading these books—I wasn’t able to get an adult library card until the age of 16, but my mam and dad didn’t seem to worry that I borrowed (read: stole) theirs. At least I was reading! And read I did, gulping voraciously on these tales of the macabre and the dead. (I would say it never did me any harm, but I expect anyone who knows me might have some long-lost memory to barter or bribe me with.) In any case, as far I’m aware, I have never murdered someone. No-one died in the reading of these tales, macabre and grotesque though they were (although we simply preferred to describe them as ‘cool’).

Sadly, many of these authors have gone the way of the dinosaur. However, since 1985, I have bought and read both Herbert and King’s novels religiously, a tradition that continues to this day (although Herbert passed away in 2013, a crushing blow). Ramsey Campbell is still active, and carries on experimenting, growing, adapting. But the halcyon days of the horror fiction boom has passed.

Or has it? There may not be legions of paperbacks in bookstores, but horror fiction is alive and well. Over the past few years, I have found myself playing catch up and have thoroughly been enjoying the ride. This year alone I have been moved, stunned and in awe of great storytelling by contemporary horror novelists. With his novel, Halycon, Rio Youers convinced me that he is the heir apparent to Stephen King. (That’s a high bar, admittedly, but I stand by it, especially after reading Westlake Souls and Forgotten Girl. You haven’t read Rio Youers? Well, what are you waiting for?).

Chad Ludzke’s tale of love and dying, Stirring the Sheets, left me emotionally and existentially shattered. Thomas Olde Heuvelt’s HEX forced me to stay up well past the witching hour (just one more page, just one more page). I was blown away by Victor Lavalle’s The Changeling, Paul Tremblay’s The Cabin at the End of the World, C.J Tudor’s The Chalk Man, Grady Hendrix’s We Sold Our Souls, John Boden’s Jedi Summer and the Magnetic Kid, James Newman’s The Wicked…

I could talk about this for ages, so I shall park this conversation for now (I can feel a research project brewing), and thus, by this circuitous route, we come to this week’s guest, Dr Xavier Aldana Reyes.

Xavier first entered my sphere with his edited anthology, Horror: A Literary History (2016), a remarkable collection of essays that covers a lot of ground. Xavier’s own chapter on ‘Post-Millennial Horror’ served as a guide to all the great horror fiction being written in the 21st Century and I hugely recommend it. In the following interview, Xavier and I get into the legacy of H.P Lovecraft, Ambrose Bierce and Algernon Blackwood as well as the Gothic imagination. I throughly enjoyed speaking with Xavier and learned a lot from our conversation (even though I ended up stocking up my online shopping basket with more ghastly tales and adventures in the macabre). I hope you enjoy the next instalment in the Cult Conversations series.

—William Proctor

How would you describe your research interests for readers unfamiliar with your work and subject area?

I mostly research Gothic and Horror film and literature, with the odd excursion into television. I am absolutely fascinated by the emotions we associate with fear, and with the idea that something fictional, in whatever medium, can move us viscerally in the ways horror does. I am also intrigued with what horror allows writers, filmmakers, scriptwriters, etc. to explore that realist genres do not. I am not merely talking about national trauma, but about the so-called ‘dark’ side of culture: taboos, ideas of ‘sin’, sexuality, social ‘others’ and so on.

I have always been fascinated by horror literature, both ‘classical’ (Poe, M. R. James, H. P. Lovecraft) and more modern (Stephen King, Poppy Z. Brite, Clive Barker). In fact, I think the first book I ever bought for myself was a Goosebumps novel – I still remember my dad cautioning me about that I would not be able to sleep that night! – and I quickly graduated to King. But I actually started out as a modern and contemporary literature student. It was only while doing my MA in this subject at Birkbeck that I came across the Gothic as an artistic mode. This capacious umbrella term seemed to conglomerate all of the artists and texts I admired. It was during an optional unit called something like ‘Gothic Bodies, Foreign Bodies’, given by Adriana Craciun (who was a visiting scholar at the time). You could say I never got over its brilliance!

Then I began a PhD under the tutelage of the wonderful Catherine Spooner, at Lancaster, and that took me, rather unexpectedly, in the direction of film. I started to explore the connections between fiction as an affective medium and cinema (and drama, as it happens!) and my PhD project changed quite substantially almost overnight. I have long been interested in horror film, but that came later in life. My tolerance for horror films was initially very low, and I even had nightmares where I tried to look away from a screen showing a horror film but my eyelids became see-through! It has rained a lot since then. I am lucky enough that I work at a place where I can develop my interests in Gothic and Horror Studies irrespective of media.

In short, I am interested in all things fictional considered dark and nasty, and am especially concerned with why they are considered dark and nasty and how they operate psychologically and socially.

Would you consider yourself a fan of the texts and objects that you study? Or put differently, what came first: fannish enthusiasm or academic interest?

It is a hard question to answer truthfully. I guess my deep interest in the topic makes me a ‘fan’, but unlike ‘fans’, I do not consume it in the same way (I have never, for example, attended a full horror festival). As I am sure any literature and film critic would corroborate, becoming an ‘expert’ in a subject ruins its initial naïve pleasures for you. You end up knowing too much about the conventions and become much more critical. Which is not to say that I no longer enjoy the topic (or that fans are uncritical) – quite the opposite! I would propose that I am now a lot more interested in the history and value of the Gothic and Horror, which, in turn, makes me more appreciative of its developments and of the contemporary writers who are doing something innovative. Being this immersed in a subject has also allowed me to discover writers and filmmakers who I would probably never have otherwise, so I guess it is swings and roundabouts. I would say my fan interest informed the critic I am today, but also that I am an atypical horror fan.

The lack of distance between fannish enthusiasm and academic interest is also what makes disconnecting from research harder: you begin reading a novel to unwind and a year later you find yourself working it into something you are writing. It is both a blessing and a curse. So I would say that there is a connection there – the fascination and committed devotion to a topic – but the fan can treasure the text as an artistic object, while the academic’s job is to contextualise, examine and explicate its value.

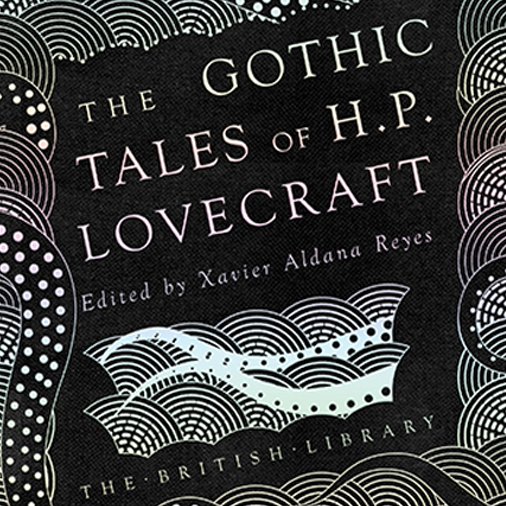

For the British Library, you recently edited The Gothic Tales of H.P Lovecraft (2018), an author that Ramsey Campbell describes as “the most influential horror of this century [the twentieth] to date,” and “one of the most important writers in the field.” Would you agree with Campbell’s assessment? It certainly appears to be the case that Lovecraft continues to be a vibrant source of intertextuality and homage in the twenty-first century both in literary quarter and across media. In comics, for example, Alan Moore’s Neonomicon and Providence both honour and expand the Lovecraftian mythos, while Matt Ruff’s novel Lovecraft Country is currently attracting much critical praise (and a HBO adaptation in the works), and Ellen Datlow’s story collection, Lovecraft’s Monsters, includes horror and fantasy alumni such as Neil Gaiman and Caitlín R Kiernan creating new material out of his legacy. What is it about Lovecraft’s writing that continues to entice and attract so many authors? Are there any adaptations, extensions or homages etc. that you think deserve attention?

Absolutely. I think that, regardless of one’s own personal opinion as concerns Lovecraft’s racism (this seems to be the topic du jour, sadly, and it is beginning to colour debates about his fiction), the legacy of his work seems to me undeniable. There is a tendency to focus on Lovecraft as the source of cosmic horror, sometimes to the detriment of other writers, like William Hope Hodgson, Algernon Blackwood, Ambrose Bierce and others, who were already treading similar territory in their writings, and to forget Lovecraft’s Gothic lineage (his ‘“Poe” pieces’, as he called them, which were the driving force for my anthology), but I do think his fiction is the epitome of weird writing and that his place as the most influential writer of the twentieth-century (perhaps together with King?) is more than warranted. I am in awe of the scope of his imagination and his idiosyncratic writing – personally, I love his cumulative purple prose, which is very baroque and similar to the overwritten style of many a Gothic novel.

You have named a few of the writers who have either homaged or expanded Lovecraft in recent years (and there are many more, even in non-English speaking countries like Spain – check out Emilio Bueso, although I do not think he has been translated into English yet), but his impact on horror is, I think, even larger. His secular, atheistic view of the world and of humanity’s place within it was ahead of its time, and it is one of the reasons why his fiction resonates so much with contemporary writers. So yes, I would never say we should forget the fact that he was an awful racist, but I certainly think that that side of his writing has not been what writers and readers have taken from his work. Lovecraft’s obsession with the limitations of language and human consciousness, with the frailty and vulnerability of the human mind and its need for rationalisation and order amidst a universe that thrives in chaos, was new, and has only been imaginatively matched in recent years by the equally brilliant Thomas Ligotti – certainly Lovecraft’s best philosophical descendant. The fact that his concepts and monsters have been able to travel across media, even to places where their lack of physical detail might have become a real burden, is a testament to the lasting power of Lovecraft’s fiction.

For readers who have yet to plunge into the abyss of Lovecraft’s fiction, is there any work in particular you would recommend as starting point?

Well, I would of course recommend The Gothic Tales of H. P. Lovecraft, as my intention with that anthology was to collect fiction that readers of more classical Gothic, say, M. R. James, who was also published in this series, might appreciate. Beginning with what he developed from Poe (in stories like ‘The Outsider’ or ‘The Hound’) and moving on to the bigger, weirder fictions, like ‘The Call of Cthulhu’, ‘The Whisperer in Darkness’, ‘The Shadow over Innsmouth’ and ‘At the Mountains of Madness’, would be how I would do it. Those are all faves of mine.

How would you describe the work of William Hope Hodgson, Algernon Blackwood, and Ambrose Bierce? As you say, Lovecraft seems to have placed those writers well under his shadow. But what is it in particular that you think reading those lesser known authors—or at least less known than Lovecraft—are worth investigating, especially for readers not familiar with those works?

As I say, there is a tendency to think of Lovecraft as someone who creates ‘cosmic horror’ in a vacuum. The reality is that, as with all genres and modes, he didn’t, at least, initially, see himself as much of an innovator. He felt ‘the anxiety of influence’, as Harold Bloom would put it, and at one point even wondered where his own tales were. It is obvious from his long essay Supernatural Horror in Literature that he was not just well read, but had a great sense of the various phases or periods of horror literature, and of where his work would eventually slot in. The chapter on ‘The Modern Masters’, where he covers Arthur Machen, Algernon Blackwood, Lord Dunsany and M. R. James, and the previous one, where he writes about John Buchan and William Hope Hodgson (Bierce is also covered in the book) are revealing, for it is precisely what he sees as innovative in these writers. For example, he praises Blackwood’s fiction for its capacity to ‘evoke as does nothing else in literature an awed and convinced sense of the immanence of strange spiritual sphere and entities’. The same comment could be levelled at Lovecraft’s weird oeuvre. So I see Lovecraft more as a pinnacle, as a melting pot of influences (the ‘Things’ of Hodgson’s fiction, the psychological and cumulative writing of Blackwood, the degeneration of Machen, the transformations of M. P. Shiel) that still managed to produce something new and powerful. It is interesting that he pins the weird tale against the bloody murder and mystery of the Gothic (his thoughts about the haunting of the past against the expansive nature of the weird are, of course, very interesting and valid), for in his fiction, he managed to often marry the two rather seamlessly.

The term “gothic” is one of those concepts that seem to resist easy categorisation. What does the term mean to you? Is there a difference between “gothic” and “horror”? Or do you think the former is utilized to validate “art” while the latter remains to be more a pejorative? In other words, is gothic literature and cinema discursively validated as “high art,” with horror continually characterised as its lowly cousin, as debased pulp or popular culture?

I have written about this quite a lot recently, both for an entry on ‘The Contemporary Gothic’ for the Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Literature, which should be about to come out, and the introduction to my current monograph on Gothic cinema. I also briefly covered it in Horror: A Literary History (with apologies for the shameless plugs!). The popular opinion is that the Gothic, previously called a genre, is rather an artistic mode that focused on the dark and the repressed, the fearful and the abject. According to this, horror would be one expression of the Gothic. It is not too dissimilar from theorisations of the ‘fantastic’ in continental Europe, although those are more dependent on the role the supernatural plays in a given text. Personally, I see horror as a genre marked by the emotional effects it attempts to elicit in readers and viewers. This means that, unlike other genres like the Western, which may be more delimited by setting and characters, horror can take place anywhere in the past, in the present and in the future. Horror is marked by its treatment of the material, in other words. Of course, as happens to all genres, notions of purity are hard to sustain, and horror comedies can merge fear with laughter unproblematically. I understand the Gothic to be an aesthetic mode delimited by its temporal retrojection to a barbaric or dark past (the medieval period initially, but increasingly the Victorian) that may manifest at the level of the building (the haunted house) and which tends to include certain characters: the villainous aristocratic, the damsel in distress, the monster. According to this line of thinking, the Gothic would be one more expression, a hybrid one that takes elements from the chivalric romance, of what has become the horror genre. Since the horror genre does not begin out of nowhere, aspects of the Gothic have been recycled and modernised. It is possible to see in the ‘final girl’ a modern version of Radcliffe’s heroines. Nowadays, I would say that a film like Crimson Peak (2015) is a Gothic horror film, but Aliens (1986) is an action film with horror elements and The Shape of Water (2017) is a monster romance with horror and fairy tale elements. For me the key indicators of a genre are its predominant emotional primers, which is why I see horror as a genre and the Gothic as an aesthetic (sometimes thematic) mode or subgenre (of horror, when the focus is fear).

To answer the second part of your question: yes, certainly. Horror is still seen as puerile, nasty and unworthy of critical study, perhaps because it is still connected in the popular unconscious with debates around misogyny in film and the ‘video nasties’. The field has truly blossomed and it is a vibrant subfield of Film Studies, but sadly, I do not know of many grants awarded in recent years to projects explicitly seeking to explore aspects of/in horror film and fiction that are explicitly called so. Although initiatives like the Horror Studies journal run by Intellect and my own book series with UWP are trying to change this cultural landscape, the tendency is still to reach out to the Gothic’s associations with history, nationality, grandiose architecture and classical literary tradition (now that the likes of Radcliffe, Walpole and Lewis have been reinstated). The Gothic has been through its own path of legitimisation since the 1980s and, actively, since the 1990s and the formation of the International Gothic Association, but for me the Gothic: The Dark Heart of Film season run by the BFI in 2013–14 and the British Library’s Terror and Wonder: The Gothic Imagination (2014–15) were real game changers that signalled the word is definitely out there in the public sphere and that it has begun meaning something to people outside academia.

The downside of the mainstreaming of the word is that it has become rather ambiguous and vague, too pliable, if you like. When the same term, ‘Gothic’ or ‘gothic’ (I still prefer the former when referring to the long literary tradition and its connection to architecture) is used indistinguishably to refer to horror fiction, dark science fiction, fantasy with some horror elements, neo-Victorian narratives and speculative fiction, getting to a core meaning of the term and thus to its operational structure becomes harder. For example, are all narratives that contain a ghost de facto Gothic? Since this indicates a reverse situation in which the Gothic is now a ‘thing’ that exists outside the ivory (castle) tower of academia, I guess I am also partly delighted. For me, the challenge is now to get to the heart of the Gothic. As it becomes, increasingly, its own set of theoretical and critical reading tools, matters are bound to get even more slippery.

It all sounds quite murky in a conceptual sense. In cinematic terms, it took Peter Hutchings and David Pirie to bring Hammer Horror out of the pop culture dungeon and into academic appreciation. But it also seems to me that early Universal monster films are imbued with gothic aesthetics, especially James Whales’ films, although not exclusively—the less talked about Son of Frankenstein borrows heavily from German Expressionism, for example. What are your thoughts about gothic cinema, if such a thing can be said to exist (although Jonathan Rigby’s series of books attest to a theoretical confluence of cinema and the gothic)? Do you see the gothic penetrating contemporary horror cinema; and, if so, what do you think are prime candidates for the descriptor? (You have already mentioned Del Toro’s Crimson Peak.)

I’m actually writing a book on the very topic (Gothic Cinema, in the Routledge Film Guidebooks series), as it happens, so I will wait until it’s out to reveal the punchline, if you don’t mind. Rigby’s books are exceptional: they are encyclopaedic in their coverage and incredibly well researched (as well as great fun to read), but no overarching thesis about what constitutes Gothic cinema really emerges from them. Or indeed of any other work in the area. Pirie’s ground-breaking book was not just the first to take Hammer seriously, but also to suggest that there might be a direct link between it and the Romantic tradition. I think there is a lot to unpack there. For me the Gothic is aesthetic and thematic, and it is pervaded by the return of the barbaric past. That often takes the shape of the chronotopic castle and the Victorian mansion. So yes, Universal’s monsters, but also early German cinema and the much-forgotten old dark house mystery. And that’s all I can say for now…

Dr Xavier Aldana Reyes is Senior Lecturer in English Literature and Film at Manchester Metropolitan University and a founder member of the Manchester Centre for Gothic Studies. He is the author of Spanish Gothic (2017), Horror Film and Affect (2016), Body Gothic (2014) and the forthcoming Gothic Cinema. He is also the editor of Horror: A Literary History (2016) and chief editor of the Horror Studies book series at the University of Wales Press (2018–).