Cult Conversations: Interview with Stacey Abbott (Part II)

/Given its historical vintage, what is it about the figure of the vampire that continues to fascinate audiences? How has the vampire been updated, revised and resurrected in different historical contexts?

Well, that is a huge question. I teach an entire module on this and only scratch the surface but here goes. I think that there are a lot of reasons why the vampire fascinates audiences. To begin with they embody taboo subjects about death, ageing, and mortality. Death remains the great unknown and a subject that we don’t talk about but, for the most part, we are all afraid of it. But the vampire confronts us with death and offers or represents an alternative. Vampires don’t age. This is both uncanny – something that doesn’t age is fundamentally weird – and attractive. Vampires are both dead and live forever. There is something terrifying and attractive about that, which in itself is part of the allure – they attract and repulse. So there is something contradictory and liminal about the vampire. They are like us but not, familiar and unfamiliar, attractive and repellent.

Vampires are also outsiders who embody transgressive identity and otherness. They usually come from somewhere else and embody the dangers and allures of strangers but they are also inherently liminal in terms of identity, gender, sexuality. Historically, they embodied an otherness to be feared – in Dracula the vampire is the foreign other infiltrating and infecting England – and this still occurs in films such as 30 Days of Night which is also about border crossing. But increasingly vampires tap into our own identification with the ‘other’ or our sense of being an outsider. This is why they have become increasingly sympathetic. Because many people are more likely to identify with their strangeness then with the Van Helsing’s of the world. So where female sexuality was punished in Dracula, it is celebrated in The Vampire Lovers and Daughters of Darkness. I think that the sense of otherness that they embody is why they have been, in recent years, so popular with teenagers. Adolescence is defined by feeling different, alien in your own body or in your social circles and the vampire is a very convenient metaphor for that sense of strangeness. In the case of Twilight the vampire offers an escape from Bella’s feelings of being awkward, clumsy, plain and also isolated. To become a vampire for her means becoming special, strong, beautiful but also to be accepted as part of a family and community – one of the cool kids. I am not saying that this is a good thing or not but I can see the attraction of this text for adolescent girls which I think is stronger than, or at least as strong as, the romance narrative. The Lost Boys offered a similar narrative with Michael on the cusp of adulthood and masculine responsibility and being presented with an alternative that embodied a more fluid conception of gender and sexuality (the film is more preoccupied by Michael’s relationship with David than with this female love interest Star). Becoming a vampire also, for Michael, means staying young and beautiful forever. The film offers a conservative conclusion where Michael rejects these temptations and accepts his place as the head of the house and as part of a heteronormative relationship, but the pleasure of the film is in the possibility of rejecting this conception of normality.

The vampire has evolved and been updated in many ways. As the world became more secular, the significance of religion to the genre waned. Films such as Near Dark and Blade throw out the old rules that seem somewhat out of date. They integrate with other genres such as the western and science fiction to refresh the conventions and make them more frightening again. The vampires in Near Dark are frightening because they are purely driven by the desire for chaos, they go anywhere and do anything. They are brutal and nothing can stop them except the rising sun. Other films from Martin to The Hamiltons to Transfiguration, present the vampire as a type of serial killer and presents vampirism as an illness or social influence, tapping into changing perceptions and conceptions of mental health. Is Martin a vampire or the victim of abuse having been told that he was cursed from an early age? One of the major trends has been the way in which the vampire has been increasingly presented as a form of disease or plague. Rather than being an individual creature invading the modern world, vampires in Ultraviolet, Stakeland, I Am Legend, and The Strain represent a plague that spreads across the world. The vampire has become more apocalyptic. This is in part a backlash, I think, against the rise in popularity of the romantic vampire in the form of Twilight but also the success of the zombie in literature, film and TV. We live in apocalyptic times and our vampires are becoming a bit more apocalyptic.

Finally, I think the vampire often challenges our sense of ‘normality’ by offering an alternative. Sometimes that alternative is positive and sometimes it isn’t but the genre constantly gets us to question what it means to be normal and what is more monstrous – the monster or normality itself.

Given that Buffy the Vampire Slayer is over twenty years old, why do you think the character remains culturally relevant? What do you think about the news that Buffy will continue in another form (and with a new slayer)?

As mentioned above, I teach a course on vampire film and television and every year I am delighted to see that a number of students have seen Buffy and define themselves as fans. Often, they have come to the show because it was recommended by a parent or older sibling but it still has currency. Yes, clothes and hair styles have changed and the computers are wonderfully dated. I mean an entire narrative strand revolves around a floppy disc falling down behind a teacher’s desk. Do modern audiences even know what a floppy is? And if Ms Calendar could have backed up Angel’s cure to the Cloud, then the story of season two who have ended very differently. So twenty years on, it is dated in places. But I believe that the horror of adolescence and growing up is timeless and by couching these horrors through the metaphor of the monster-of-the week allows the series to transcend the trappings of time period. Issues such as bullying, social anxiety, loneliness, internet predators, sexual violence and domestic abuse are timeless and the monster narratives explore these in detail.

As a feminist text, the focus on not just a kick-ass heroine but a woman trying to negotiate her path in the world and standing up to patriarchy – whether in the form of the Watcher’s Council, the high school principal, the Mayor, a dominating father or the Initiative (which is yes led by a woman but is a government run, patriarchal institution) – still holds sway. Buffy gives a speech about power in the episode ‘Checkpoint’ (5.12) as she confronts the leaders of the Watcher’s Council who have attempted to diminish her self-confidence in order to assert control over her. She tells them how everyone has been ‘lining up to tell me just how unimportant I am. And I’ve finally figured out why. Power. I have it. They don’t. This bothers them’. This speech stands as a testament to how patriarchy and any form of dominant social order often attempts to maintain its position by belittling and undermining those they are attempting to control. The best way to assert control is to convince others that they need authoritative rule. The way in which she pauses the narrative to stand up to this authority and diminish their power by revealing their machinations – as well as throwing a sword at one of them (well who hasn’t wanted to do that) – is as timely today as ever. Buffy is about power: female power, the power of family, friendship, the sharing of power and the dismantling of power.

Of course, the show isn’t perfect and it is a product of its time. When it was on the air between 1997-2003, there were very few LGBTQ characters on network television and having Willow come out was incredibly progressive for the time. But now it is far more commonplace on television and the hesitancy in showing Willow and Tara kiss or display their sexuality in an overt way, particularly in season four and five, seems old fashioned now. Similarly, the character Xander Harris has received a great deal of criticism in recent years, particularly in the #metoo era, because his treatment of Buffy is often seen as problematic. Most notably, the series has received a great deal of criticism for its depiction, or lack thereof, of people of colour. They are either absent, demons or stereotypical. The spin-off Angel tried to compensate for this by being set in a more multi-cultural Los Angeles and featuring the African American character Gunn as a regular. But there remain issues and there has been a great deal of discussion of this theme with respect to both shows.

This was why I was not surprised when I heard the news about a new Buffy series that would be more multi-cultural and socially inclusive. Originally couched in the media as a reboot, I was initially quite sceptical. Why reboot Buffy as it is a loved series that is skilfully written and directed and that still holds up as quality television? Yes, there are issues but they are part of its place within a period of television history. Also, rather than reboot an old show with a multicultural cast, it seems more useful to create something new with a multicultural cast. But as more came out about the project and the new showrunner, Monica Owusu-Breen, it became clear that this isn’t going to be a reboot but rather than an extension of the narrative world and potentially something quite new. A new Slayer with new stories and I am all in favour of that. I think that there is a lot of scope in the story line and potential to update the Slayer narrative to suit the current televisual landscape. This seems ideal to me as you will introduce Buffy to new audiences while appealing to established fans of the original series. I look forward to seeing what Owusu-Breen has in mind.

What are you working on at present and what have you planned for future research?

I have a few projects in various stages of development. I am currently co-editing, with Simon Brown, a special issue of Slayage, reflecting on the legacy of Angel which will be published to mark its 20th anniversary in 2019. The more I watch and rewatch Angel, the more Angel’s struggle to negotiate the moral grey areas of adulthood feels relevant. Also, the way in which the show challenged and undermined traditional notions of masculinity still feels fresh and pertinent within the contemporary televisual landscape. The decision to replace Sunnydale’s Hellmouth under the high school with the multi-dimensional corporate lawfirm Wolfram & Hart as the site of all evil seems to speak volumes to the horrors of the 21st century. This show isn’t about one named and clearly identifiable Big Bad but a patriarchal culture of evil that is fuelled by big business. Its mantra that you have to keep fighting even when the odds seemed stacked against you feel like an important lesson in the contemporary climate.

Lorna Jowett and I are co-editing a book for the University of Wales Press on Global TV Horror. We wanted to follow up our TV Horror: Investigating the Dark Side of the Small Screen (2013) with something that reflected on the growing popularity and availability of horror on television and its increasing global presence. So this is an exciting project, working with people writing about TV Horror from around the world, including the UK, US, France, Brazil, Spain, Japan, New Zealand and Canada.

As for my own writing, I am very excited to be writing the BFI Film Classic on Kathryn Bigelow’s Near Dark (1987). This was Bigelow’s first solo-directed film and I would argue it remains one of her most visually and narratively striking films. It did not do very well when it came out but it found a cult audience on video in the late 1980s. Narratively it follows a young man, Caleb, who is turned into a vampire and must decide if he is prepared to give up family, responsibility and his humanity in favour of the outlaw life of a vampire. The vampires – particularly as played by Lance Henrikson, Bill Paxton and Jenette Goldstein -- are far more engaging and attractive despite their undeniable blood lust and violence. Significantly they seem to both embody the dark side of the nuclear family while also representing an alternative to traditional family values. This film raises some really interesting questions about blood, duty, family and chosen families. It has been criticized as featuring a conservative ending, much like The Lost Boys, but I am inclined to read the film as more ambiguous in its politics and that is something I’ll be discussing in the book. Visually it merges the vampire and horror genre with the western and road movie and features stunning Noir-ish night time cinematography and Bigelow’s recognisable kinetic style. It is a delight to begin to unpack the film’s complexities, both narratively and visually, in this book.

In terms of future projects, I am in the process of developing two long term projects. The first is a co-authored book with Simon Brown, looking at the horror genre through adaptation. This isn’t going to be a book that simply compares ‘original text’ with adaptation. As I said above, I am very interested in media specificity and so this book will consider how the horror genre adapts to different forms and media. So we will be looking at adaptations of horror from novel to film, film to stage, comic book to television, and so on. It is a great time for horror and we have enjoyed doing some of the preliminary work on this by going to see the stage adaptations of Let the Right One In, Carrie, and The Exorcist and thinking through the different ways in which horror is adapted to suit different media and performance styles.

The other project is a monograph on horror and animation, bringing together two of my great loves. I have been teaching the History of Animation for years but this will be my first foray into animation in terms of my research. There are two strands to this project. I am interested in the presence of horror in media for children from Scooby Doo to Nightmare Before Christmas to ParaNorman. How and why are the tropes mobilized for this particular audience and to what end? Is horror rendered safe through animation? But I am also interested in the ultimately uncanny nature of animation – making the inanimate animate – which comes to the fore in stop-motion animation. So my work in this book will not be exclusively focused on children’s animation or even narrative film but it will look at works that galvanize the surrealism and uncanniness of stop motion – so lots of Svankmajer. As I said, both projects are in early stages and I am still developing my ideas.

And finally, what five films or television series would you recommend that you feel represents ‘the best’ that the horror genre can offer and why?

If I have to limit my choices to five then I will not include any of the texts I have already discussed in detail here, including Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Angel and Near Dark. It seems better to open up the discussion to significant texts that I haven’t had the opportunity to talk about in any detail.

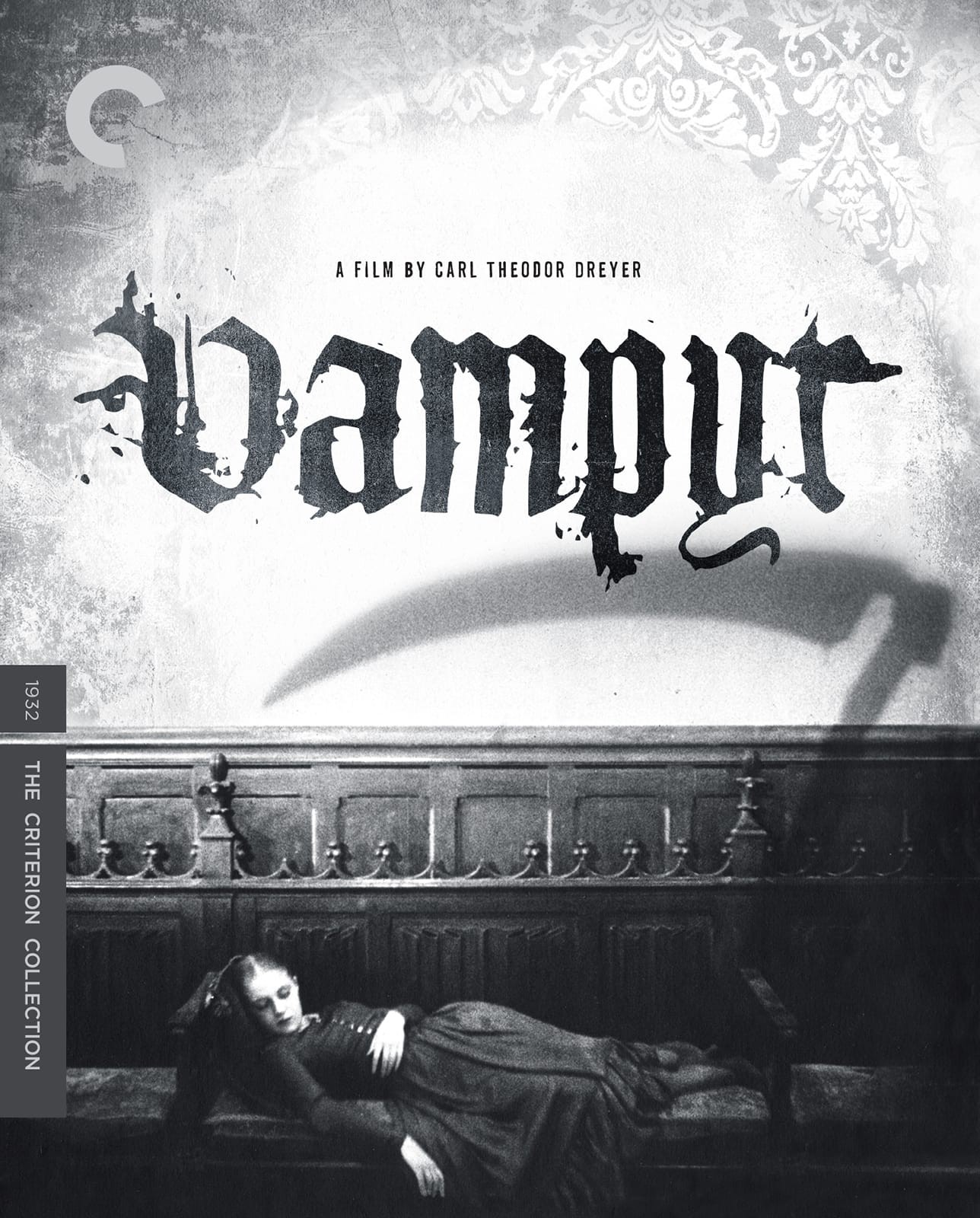

Vampyr (Carl Theodor Dreyer Ger 1932)

This film embodies the Gothic potential that is an inherent part of cinema. Taking place in a landscape that seems to exist on the border between reality and dreams, life and death, it tells a familiar vampire story – woman is fed on by vampire until vampire is destroyed and she is released -- but told in a distinctly cinematic fashion. It is filled with disembodied shadows, superimpositions and double-exposures, alongside a ghostlike roving camera, a disjunctive use of sound, and a mise-en-scène filled with momento mori, including skulls, skeletons, and Grim Reapers. Watching this film is like being invited to cross the veil into the land of dreams and nightmares where you are never certain what is real and what is not. It is a haunting landscape of the undead.

Les yeux sans visages [Eyes without a Face] (George Franju, Fr 1959)

This is a haunting film of a completely different kind that feels up-to-date with a vengeance. Set in contemporary Paris, it tells the story of an internationally leading plastic surgeon whose daughter has been severely disfigured in an accident and so he attempts to repair her through a face transplant. The only problem is whose face is he transplanting? The doctor’s nurse stalks the streets of Paris, looking for isolated young women to lure back to the surgeon while the daughter Christiane wanders her family home, wearing an exquisite and yet disturbing porcelain mask that makes her appear as a ghost haunting the family home. Like contemporaneous horror films, Psycho and Peeping Tom, this film reimagines horror as emerging from family and home – no longer a source of comfort and security but the birthplace of the monstrous. Additionally, the surgery scenes are filmed with medical precision and lend the film a gruesome form of body horror that continues to unsettle even the most committed horror fans.

Night of the Living Dead (George A Romero, USA, 1968)

A landmark independent horror film that contributed to the transition of horror away from the period Gothic tales to contemporary horror. A siege narrative about a group of strangers trapped in a house as the dead return from the grave with a hunger for human flesh, this film (along with its sequel Dawn of the Dead) established the template for the contemporary zombie film. Filled with decomposing zombies, graphic depictions of cannibalism, and explosive confrontations between the living, the film offers a nihilistic view of humanity that became typical of the period. Featuring an African-American lead, the film taps into the culture of racial tension that surrounded the Civil Rights movement and still fills relevant today. Significantly, Romero shot the film with gritty, realistic aesthetic that rendered the horror all the more unsettling and contemporary. Using the rise of the undead as a threat to the status quo, the film questions who are the more monstrous the zombies or the living.

American Mary (Jen and Sylvia Soska, Can, 2012)

Canadian filmmakers Jen and Sylvia Soska offer us a distinct and disturbing twist on the rape/revenge formula presented with Cronenberg-esque fascination with body horror. The film tells the story of a medical student who pays for her education by performing underground, illegal extreme body modification surgeries. After she is drugged and raped by a group of her medical professors and tutors, she drops out of school and decides to use her body modification skills in an unusual and cathartic form of revenge. This is a film that challenges notions of beauty and the monstrous, normality and the disturbed. It offers a distinctive female perspective on violence and rape while also confronting the audience with provocative images of the body that unsettle traditional conceptions of cinematic beauty and voyeurism. It is a fascinating film that does not disappoint.

Hannibal (Bryan Fuller, US, 2013-15)

The past ten years has been an incredible period for the horror genre on television with so many amazing series, pushing the boundaries of what is acceptable on television. Hannibal stands as an exciting example of the potential for network television to be as provocative and experimental as cinema. Based on characters from Thomas Harris’ Red Dragon, the series infuses the police forensic procedural with the aesthetic tastes of serial killer Hannibal Lecter. Each episode contains a crime scene that is laid out like a work of art, blurring the lines between the macabre, the gruesome and the beautiful. This is a series that challenges us to sympathise with Hannibal while also confronting us with the horrors of his actions. Focusing on the relationship between Hannibal and FBI profiler Will Graham, the series becomes increasingly experimental in its style, blurring the lines between nightmare and reality as Graham comes increasingly under Hannibal’s influence. This is an aesthetically rich series with lush visual style and an experimental musical score like nothing you’ve ever heard before. It is a must watch for the horror film.

Stacey Abbott is a Reader in Film and Television Studies at the University of Roehampton. She is the author of Celluloid Vampires: Life after Death in the Modern World (2007), Angel: TV Milestone (2009), Undead Apocalypse: Vampires and Zombies in the 21st Century(2016), and co-author, with Lorna Jowett, of TV Horror: Investigating the Dark Side of the Small Screen (2013). She has also written extensively about cult television and is the editor of The Cult TV Book (2010), Reading Angel: The TV Spin-Off with a Soul (2005) and TV Goes to Hell: An Unofficial Road Map to Supernatural (2011). She is currently co-editing, with Lorna Jowett, a book on Global TV Horror and is writing the BFI Classic on Near Dark.