Popular Religion and Participatory Culture Conversations (Final Round): Sarah Banet-Weiser and Hannah Scheidt (Part 2)

/Hannah: Thanks for sharing this introduction to your current project. You define and develop key concepts for understanding the current sociopolitical climate and its media stage. One concept or theme that intersects with my own work (and that religious studies can offer some insight into) is that of “narratives of injury.” You identify a narrative of injury at work in the contemporary white nationalist movement, and an accompanying narrative of restoration or redemption of sorts, though this side of the story seems perhaps less visible (let me know if you disagree).

This basic story line, which involves a threat, a victim, and the violation or disruption of the status quo, is familiar to me as a narrative of persecution. Scholars of religion have explored the operation of these types of narratives in countless religious communities, from ancient Judaism and early Christianity to New Religious Movements.

Specifically, though, because we are talking about the modern American context, I thought immediately of Christian Smith et al.’s sociological study (now two decades old) on American evangelicalism: American Evangelicalism: Embattled and Thriving. Smith argued basically that evangelicals are not only “embattled” and “thriving” but are thriving because embattled. His notion of “subcultural identity theory,” suggests that groups take advantage of “embattled” status in their projects of identity formation. Identity construction is a process of drawing symbolic boundaries; categories of differentiation and comparison vis-á-vis outgroups aid in the project of collective identity formation and promote solidarity.

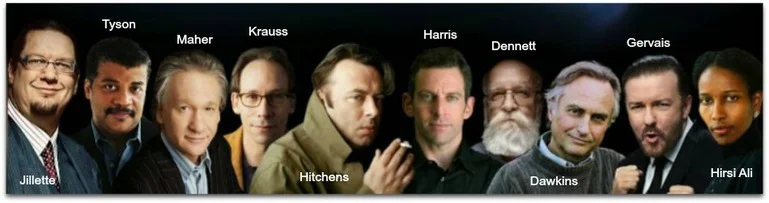

“Subcultural identity theory” is obviously portable, and some have applied it (rightly, I think) to New Atheism, within which a narrative of opposition and persecution exists (hence the need to “come out” as atheist) (Cimino & Smith 2011,LeDrew 2015). What I find interesting in contemporary atheism is that this narrative of an embattled minority exists in tension with other formative narratives: that there are actually more atheists than polls and statistics account for, for example, or the understanding that secularization is an immutable process and that “reason will reign.”

It is worth noting that in both of our work, opposing movements or cultures employ similar narratives of persecution and of injury (atheism and evangelicalism, feminism and white nationalism). I wonder if we could start to talk through a more robust accounting of how similar logics and strategies operate in competing or opposing groups. I think you could find examples of how each group imagines an alliance between the opposing ideological group and “the mainstream” (institutional powers that be, the mainstream media). This is essential, as the threat must be imagined as dominant, structural, hegemonic – not as another subcultural minority.

The media studies perspective contributes an analysis of how narratives of injury circulate, and the form they take in the “economy of visibility.” I am curious about the transmutation of politics into visibility, as you describe it, in the case of coverage of white nationalism. I do wonder if a media outlet’s focus on, for example, the fashion choices of a neo-Nazi could be read as intended not to normalize but to unnerve – a version of the handsome and charming serial killer narrative. So instead of reading “Nazis, they’re just like us,” the consumer comes away with “Nazis…they could be anywhere.”

Sarah: hmmm, I’m not sure. I don’t think the mainstream media generally try to unnerve, even if that may well be the effect of some representations. I think that the mainstream media, and journalists in particular, are in a difficult place in the contemporary moment, in the context of misinformation, disinformation, and post-truth. I see stories such as “The Nazis next door” as part of that context, which works for the mainstream media to normalize in the name of “we cover different perspectives;” in this sense, it is related to Trump’s statement about the racist Unite the Right rally at Charlottesville as having “very fine people, on both sides.”

I really like the idea of “thriving because embattled” because I see that affect increasingly gaining currency in the contemporary context. We hear about white men in the US being victims all the time—this sentiment was on glorious, devastating display in the Brett Kavanaugh hearings. He claimed victimhood through his white masculine rage, a rage that was then bolstered by Lindsey Graham’s similar explosion where he vowed to “not ruin a man’s life” over accusations of sexual assault. Tragically, it is no surprise that women’s lives, and how they are ruined over and over again because of sexual violence and not being believed, was not part of Graham’s rant. We can see, in the contemporary media and cultural climate, how claiming male (especially white male) victimhood actually strengthens and supports masculine hegemonic status.

I’ve been writing about what I’m calling “feminist flashpoints,” stories that get wide immediate visibility in the media, but then quickly are obscured by the circulation of yet another story, another abuse of power. In terms of white nationalism, I think that a focus on “fashy fashion” or the fact that Nazis buy milk just like the rest of us, is part of this obfuscation. The temporality and rapid circulation that mobilizes an economy of visibility often means constant production, not reflection. In the current media economy, the need to constantly gain new followers means that there needs to be constantly new and potentially flammable material. And rage is perhaps the most flammable material—but we need to remember that white men are not only encouraged to be full of rage, it gives them even more power. In contrast, the rage of women and people of color is routinely dismissed as hysteria, insanity, or ignorance.

Sarah Banet-Weiser is Professor of Media and Communications and Head of the Department of Media and Communications at LSE. Professor Banet-Weiser earned her PhD in Communication from the University of California, San Diego. Her research interests include gender in the media, identity, citizenship, and cultural politics, consumer culture and popular media, race and the media, and intersectional feminism.

Hannah Scheidt recently completed her PhD in religious studies from Northwestern University. Her dissertation, a cultural study of contemporary atheism, was informed by perspectives from religious studies and media studies. The dissertation shows how "atheism" is constructed through a complex relationship with "religion" - a relationship that involves critique and contrast but also imitation and resemblance. Her other research interests include religion and science, transhumanism, and (newly) American craft and maker movements.