Unspreadable Media (Part One): The Geographies of Public Writing

/At the 2016 Society for Cinema and Media Studies conference in Atlanta, I participated in a panel, “If It Doesn’t Spread, It’s Dead?: Finding Value and Meaning in Unspreadable Media”, which was chaired by Sam Ford and included perspectives by Lauren Berliner and Leah Shafer. The discussion which emerged there was highly generative, allowing Sam Ford and I to clarify and revisit some of the key assumptions behind our book, Spreadable Media: Creating Meaning and Value in a Networked Society, and introducing us to the work of a new generation of researchers exploring the politics of circulation as it relates to civic and activist media. We hatched a scheme to translate the panel into a series of entries for my blog, where we could share and discuss our work. It’s taken longer than expected to get to this point, but over the next four posts, I am going to share the original papers presented at the conference, and then, we will share some reflections from the panelists about how their thinking has or has not shifted over the intervening months, especially in light of the election results this fall, which shook up so many of our assumptions about the state of American politics. I would welcome hearing from other researchers who are exploring some of these same questions through their work, as would the other panelists, so let us know what you think.

The Geographies of Public Writing: Genres of Participation and Circulation in Contemporary Youth Activism

By Henry Jenkins

This essay is intended to map points of intersection between two of my books -- Spreadable Media: Creating Meaning and Value in a Networked Society (With Sam Ford and Joshua Green) and By Any Media Necessary: The New Youth Activism (with Sangita Shresthova, Liana Gamber-Thompson, Neta Kligler-Vilenchik, and Arely Zimmerman). My goal here is to show the relationship between the concept of circulation discussed in Spreadable Media and the concept of mobilization discussed in By Any Media Necessary.

This essay is also inspired by John Hartley’s now classic essay, “The Frequencies of Public Writing,” which first appeared in my edited collection, Democracy and New Media.

“Time in communicative life can be understood not merely as a sequence but also in terms of frequency…Time and news are obviously bound up in each other. The commercial value of news is its timeliness.”-- John Hartley

John Hartley’s “The Frequencies of Public Writing” maps the different time scales upon which communication operates, with public writing being deployed to describe a broad range of forms of cultural production which seeks to inform and mobilize public thought. In the essay, Hartley defines “frequency” in terms of:

- The Speed of Creation: How long a text takes to be produced

- Frequency of Circulation: Intervals between publication

- The Wavelength of Consumption: How long before the text is superseded.

Hartley charts a spectrum of communicative frequencies which runs from the instantaneous to the eternal, a scale inspired in part by the focus on temporality and spatiality in the writings of Harold Innis.

Frequencies of public writing

- Before the Event Previews, Leaks, Briefings, PR, "Spin"

- High Frequency

- Instant/Second Internet, Subscription News: e.g., Matt Drudge; Reuters Financial TV, Bloomberg.com

- Minute "Rolling Update" News: e.g., CNN, BBC-24/Choice, Radio 5-Live

- Hour Broadcast News: e.g., CBS/ABC/NBC, ITN/BBC, Radio 4

- Day Daily Press: e.g., The Times, New York Times, Sun, New York Post

- Week Weekly Periodicals: e.g., Time, New Statesman, Hello!,National Enquirer

- Mid-Frequency

- Month Monthly Magazines: e.g., Vogue, Cosmopolitan, The Face,Loaded

- Quarter Scientific and Academic Journals: e.g., International Journal of Cultural Studies

- Year Books, Movies, Television Series: e.g., Harry Potter, Star Wars, Ally McBeal

- Low Frequency

- Decade Scholarship, Contemporary Art: e:g, "definitive" works, textbooks, dictionaries, portraiture, fashionable artists

- Century Building, Statue, Canonical Literature: e.g., Sydney Opera House, war memorials, Shakespeare

- Millennium Temple, Tomb: e.g., Parthenon, Pyramids

- Eternity Ruins, Reruns: e.g., Stoneh

Innis, as we discussed in Spreadable Media, identifies the “biases” of different historical cultures in terms of the ability to spread information rapidly across large distances (those based around Papyrus) and the ability to preserve information unchanged across large spans of time (those based around marble). Hartley’s model, on the other hand, is based on genres, with contemporary cultures developing a broader array of different forms of communication which allow them to circulate information over different geographic scales and preserve information across different chronological scales.

Hartley’s use of the term circulation above reflects a classical understanding of the concept which stresses the intended or achieved audience for mass-produced content. In Spreadable Media, we adopt a somewhat different use of the term to refer to the hybrid systems --partially top down, partially bottom up -- through which content spreads within an era of social media, a term we use in contrast with distribution, which describes the now mostly corporate and planned mechanisms for spreading content.

Hartley is interested in the ways that different genres of public writing contribute to the development of core civic identities and basic social agencies, the ways that our ability to act as citizens is bound up with the circulation of information. Hartley writes, “Once virtualized, a sense of civic or national identity is also rendered portable. It can be taken to all comers by contemporary media, which is centrifugal, radiating outward to find spatially dispersed addresses—the ‘imagined community’—at any moment.”

Hartley’s use of the term, “imagined community,” here is helpful, evoking Benedict Anderson who also had developed a conceptual framework for thinking about acts of publication and forms of collective identification. His best known example is the ways that the London Times developed a collective sense of belonging across the British Empire. For now, we can think of the global reach of the British Empire, then, as representing perhaps our most expansive understanding of the scale on which public writing can occur.

To adapt a more recent example, we might think about Michelle Obama’s participation in the #BringBackOurGirls campaign directed against Boko Haram. Here, the first lady of the United States deployed social media, participating in a popular form of hashtag activism, in order to send a message to a terrorist group operating in Nigeria, relayed along the way informally via social media platforms and formally via more traditional news media.

As we suggest in By Any Media Necessary, such exchanges, which require the active mobilization of large communities of people and often creative acts to repurpose and reframe existing memes, might best be understood in the more active sense of imagining communities rather in Anderson’s more passive formulation, imagined communities.

Another spectacular example of global or at least transnational circulation of information was Kony 2012, a public awareness campaign conducted by the organization, Invisible Children, in order to call attention to the activities of an African warlord known for his ruthless efforts to kidnap children from villages in Uganda and turn them into soldiers in his resistance movement. As Sangita Shresthova discusses in By Any Media Necessary, Kony 2012 helps us to understand the consequences of a dramatic shift in the geographies of public writing. The campaign’s organizers had estimated that the video might reach as many as half a million viewers over roughly two months of circulation; instead, it spread to more than 100 million viewers during its first week.

The organization was in no way ready for this level of circulation, which had destructive effects in both the short run and the long run. In the short run, the expanded circulation crashed their servers, brought the messages to many unintended audiences, rushed ahead of their efforts to build web resources around the campaign, lead to the nervous breakdown of the organization’s leader. As the group’s leaders circled the wagons to deal with the crisis, many of the more outlying participants were ill-prepared to respond to the backlash the video would generate. The group had felt so strongly that their message was “common sense” that they did not train members to anticipate and respond to objections. In the longer term, the high visibility of this one message led many to imagine the group was more fully established than it was, and as a consequence, donations slowed as many assumed the group no longer needed their support.

The example of Kony 2012 illustrates two potential negative consequences of the unpredictable nature of today’s circulation practices: The Digital Afterlife,a term coined by Lissa Soep, refers to media content that remains in circulation longer than intended and thus re-emerges in unanticipated contexts. For example, in the case of Kony 2012, photographs of the IC leaders taken during an earlier trip to Africa and showing them holding machine guns were rediscovered and turned into a meme that was deployed to ridicule their self-aggrandizing tendencies. We might think of this problem as arising from shifting temporalities of communication. On the other hand, danah boyd and Alice Marwick, among others, have used the term, “context collapse,” to refer to what happens when a message travels beyond its intended audience, a problem having to do with the geographies of public writing. In this case, IC had intended the Kony 2012 message as helping to mobilize a community that they had already initiated into their movement through previous grassroots recruitment efforts at schools, college campuses, and churches. As the message reached many more who did not understand the group’s history and mission, there were questions raised the group was unprepared to answer. Or consider, for example, what happened when the sermons of Rev. Jeremiah Wright, posted on line to be shared with worshippers in his congregation, became more widely spread and surfaced as a divisive issue in Barack Obama’s campaign for the presidency.

There has been a tendency, as people have read Spreadable Media, to assume that the only communicative acts that matter are those which occur on this most expansive scale -- in part because, as Sam Ford suggests here, we still tend to measure success according to the standards of the broadcast or mass media paradigm. Yet, in fact, meaningful communication can occur on the hyperlocal scale -- so imagine a high school newspaper or a website focused on sharing the news of people living in a particular apartment building or neighborhood. Here, the scale of circulation is much more limited, but still reaches the local audience for which the information was intended, and this exchange can have the desired result of mobilizing people to act on their shared interests and producing a collective civic identity. So, rather than assume all public writing today is designed to reach the largest possible audience, we might assume organizations are making choices about how wide a geographic reach they hope to achieve, albeit choices that can not be enforced upon those circulating their content given the dual threats of digital afterlife and content collapse.

Such intentions about the scale and speed of circulation, about temporal and geographic dimensions of public writing, might be understood as one aspect of what social scientists have begun to describe as “genres of participation.” As Marie Dufrasne and Geoffrey Patriarche tell us, genres of participation refer to “a type of communicative action recognized by a community…as appropriate to attain a specific objective.” Genres of participation express “collective convictions” by describing particular sets of actions (in this case, communicative practices) which provide templates that can be performed by diverse sets of participants. These genres of participation address central questions regarding why, how, what, who/m, when, and where. These genres of participation provide those who join these actions with a sense of shared purpose and practice, increasing their sense of collective civic agency. Consider, for example, the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge, which offered a script to participants in terms of what actions should be taken, what messages should be delivered, how this media should be directed towards particular networks, how to motivate those who receive the message to re-perform and recirculate the message, etc. As a result, this communicative action reached very large scales of participation and raised massive amounts of money for its cause. While there was some degree of social embarrassment built into the Ice Bucket Challenge, it was ultimately designed to be understood and embraced across diverse communities and networks.

By comparison, in her research on the Nerdfighters, a youth movement that grew up around the online personalities, John and Hank Green, Neta Kligler-Vilenchik encountered examples of much more localized genres of participation. For example, young people often produced videos addressing political topics while spreading peanut butter on their faces, a gesture meaningful within their subculture but that limited the comprehensibility of the message to the outside world, especially in terms of institutionalized authorities who might have the capacity to act upon their social concerns. This is a genre of participation, then, which strengthens ties within a community but does not serve its cause as it spreads beyond its intended context.

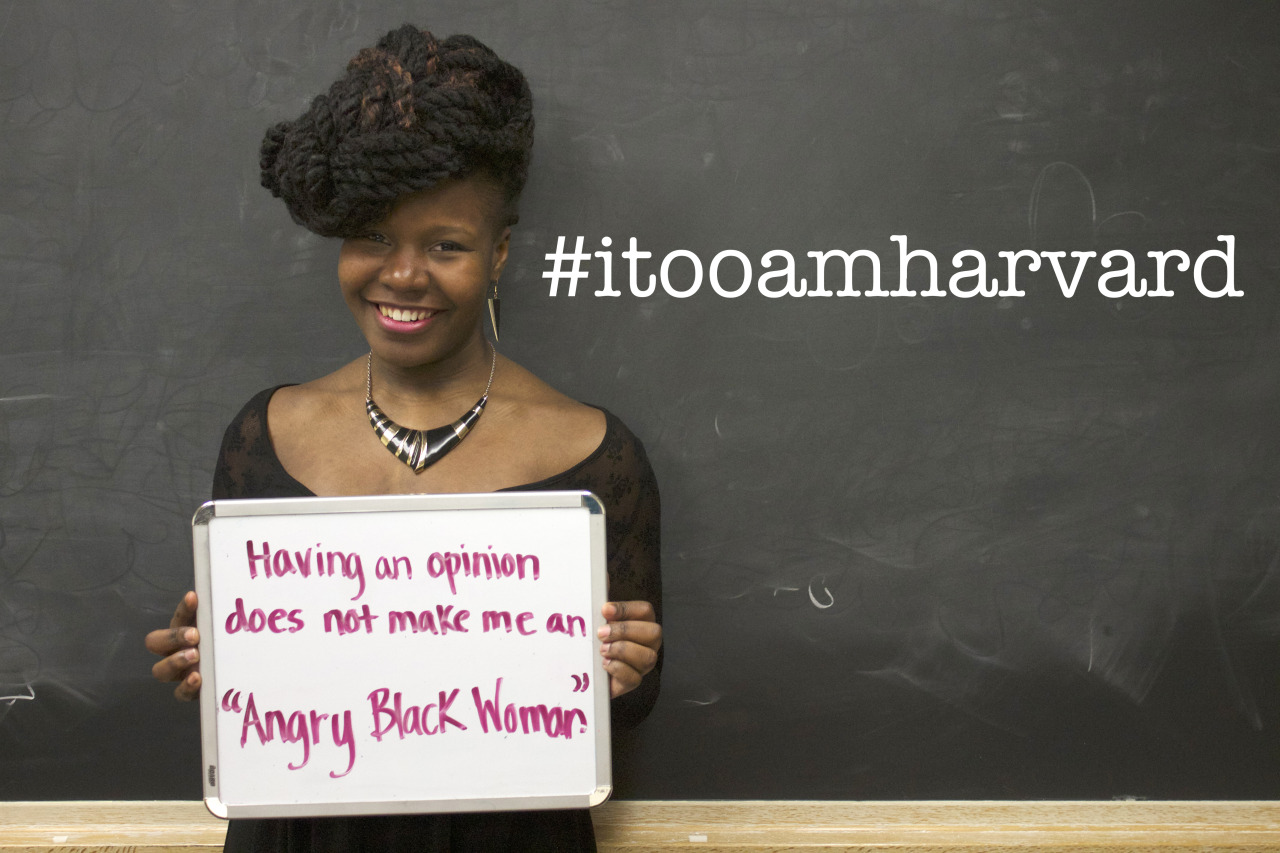

Of course, the expansion of genres of participation do not always bring about negative effects or insure incomprehension. #Itooamharvard was initially a hyperlocal genre, as Harvard students of color were photographed holding signs that shared negative, stereotypical, and hyper-aggressive comments directed against them on the basis of their race, gender, or sexuality during their time on campus. The goal was to stir debate about campus climate at a specific location, but the template for this activity has proven highly generative (resulting in similar efforts on many different college campus), especially at a time when campus climate issues are gaining greater visibility across the country.

This concept of genres of participation helps us to distinguish between campaigns which are directed inward towards would-be participants who already see themselves as part of a specific community and those which are directed outward towards a more generalized public. For example, Neta Kligler-Vilenchik’s account of fan activism in By Any Media Necessary makes a core distinction between fannish civics (where elements of fictional storyworlds are deployed in ways that depend on the deep expertise of the fan community) and cultural acupuncture (where campaigns tap more broadly recognized aspects of popular franchises in order to create more generalized interest.) She locates examples of both sets of practices within campaigns conducted by the Harry Potter Alliance, Imagine Better, and the Nerdfighters.

Some groups increase their leverage the more visible their public writing becomes, often seeking to expand beyond an initiated dedicated core to signal more widespread support (through retweets, for example) as they seek to move a more powerful institution. Consider, for example, #iftheyshouldgunmedown, a protest effort that emerged in the wake of the Ferguson shootings.

The group wanted to call out the news media for choices it made in how it chose to represent the victims of police violence, in particular the tendency to use “thugish” images to illustrate their stories, images selected from a broad range of representations of these young men and women found within their social media flows. This effort provided participant with a clear template for what they were meant to do: each participant selected two photographs, one that might be seen as grubby, the other as more respectable, which were tweeted together to illustrate that the same person might adopt a range of personas across their everyday interactions. The goal was to let the news media know that there was broad disappointment across their community about their selective bias.

Yet, for many activist groups, there is also a risk that comes from expanded circulation. Arley Zimmerman and Liana Gamber-Thompson have documented in By Any Media Necessary the efforts of the DREAMers, undocumented youth fighting for greater educational and citizenship rights, to use confessional videos to expand their reach. As their movement began, many potential participants did not know each other because they were hiding their immigration status, so the practice of “coming out” via a video and in the process, telling their stories, was seen as an effective tool for fostering solidarity. The videos also had a positive impact in that they could be circulated within a range of other communities and networks to which these youth claimed affiliation. Most Americans did not know they knew anyone who was undocumented so hearing stories of people who shared their interests or backgrounds, people who they might already know, helped to pull many new supporters to the cause.

But the more widely the videos circulated, the more likely they were to have negative effects, since coming out exposed undocumented people to greater scrutiny from immigration authorities or left them vulnerable to third parties who might report or harass them. Here, expanded circulation, then, is a mixed blessing, and the group hoped to direct the flow in such a way to maximize benefits and minimize risks.

Sangita Shresthova identifies similar tensions between the desire to bring their message to more diverse audiences and anxieties about forms of surveillance brought about by such exposure that shaped the communication practices she observed amongst American Muslim youth (another case study in By Any Media Necessary). Often, the result was a series of lurches as participants pushed for expanded reach during what they felt were relatively safe times and more constructed circulation during times of heightened risk and scrutiny (for example, following the Boston Bombing).

Just as the same culture may support communication with different degrees of frequency, each serving different functions, the same social movement may develop practices intended to reach different geographies of circulation, sometimes even using the same platforms to post and spread their content. So, a recent study of the Occupy Movement’s use of social media, found tens of thousands of videos posted on YouTube and publicized through Twitter and Facebook. In some cases, these videos reached only a small number of viewers, since the movement was using YouTube, in these instances, primarily as an archival media rather than as a mechanism for publicity. Videos might be posted to allow people at different Occupy sites to share practices or report on outcomes, thus the scale of exchange was modest, reaching only people already known by the video’s producers. In other cases, though, YouTube videos reached a much wider circulation, since the movement was using the platform as an alternative mechanism for reaching the public at a time when their protests were receiving only limited attention through the mainstream media. Many of the videos fall someplace in between: the potential of broader reach, of context collapse and digital afterlife, surrounded all of these videos, but in practice, only certain videos broke free of their intended spread.

Much more research and reflection needs to take place before we can develop a map of the potential geographies of media circulation that are as robust as Hartley’s chart of the frequencies of public writing. I hope that in tapping some of the cases we’ve identified around our book, By Any Media Necessary, I’ve modeled what such an analysis might look like. The first step is recognizing that people intend their public writings to reach communities on a variety of scales and that negative consequences can occur when they move beyond their intended audience.