The Czech Zine Scene (Part 4): Computer Games

/Cassette Covers

Baby Steps in Machine Code

By Jaroslav Švelch

—

“Our computer scene is like a theatre stage, where a play consisting mainly of isolated monologues is being played. Around a half-empty town square dominated by the big sign that says NOT AVAILABLE, followed by a long list in small print, there are many doors, behind which one can hear some lively commotion" (Bohuslav Blažek, academic, writer, and a proud owner of a Commodore 64, 1990).

Being a computer fan in Normalisation-era Czechoslovakia wasn't easy. Domestic machines were few and far between, and Western ones were seldom imported. Playing and programming on 8-bit machines had an air of a subculture conspiracy around it, as well as that of a local DIY culture. What was going on behind those doors on that “semi-empty town square” was lots of soldering, programming, playing, and also publishing of club newsletters, which were a substitute for then non-existent computer magazines.

Communist technocrats had an ambiguous attitude towards computers, one which bordered on hypocrisy. On one hand, they loudly proclaimed support for the automation and electrification of industry and, to an extent, also the educational system; on the other hand, they were indifferent to the cries of ordinary consumers for affordable domestic machines. The state apparatus saw computers primarily as a means for speedier and more efficient manufacturing processes. They weren't supposed to be used “for their own sake”, or for the joys and pleasures of individuals, but for the “fulfilling of decisive tasks of the national economy.” Unless one worked in a computing department, they were out of luck in coming into contact with the desired machines. As the local computer guru Eduard Smutný remarked in 1989: “In our country, no one is responsible for the production of personal microcomputers. No one was assigned that task, no one had to complete it, and therefore no microcomputers are available.”

People didn't give up. From the start of the eighties, they brought back (or had brought back) computers from the West, mostly the cheapest 8-bit ones. Sometimes an uncle who emigrated or a friend who travelled abroad on business trips would help out. Fourteen year old David Hertl from Lenešice in Northern Bohemia—future publisher of the ZX Magazín fanzine—had his brought to him by his father, who worked as an electrician in friendly countries in North Africa. When he was returning home via Amsterdam, he purchased the British Sinclair ZX Spectrum computer at the airport.

Soon, the Spectrum in particular became the most popular model among local fans, thanks to its low price and probably also its portability. As one contemporary recalls, an acquaintance smuggled his Spectrum disguised as “a sandwich, hidden in a basket among other sandwiches.” In the second half of the Eighties, tens of thousands of Czechoslovaks would thus own computers. Amongst these were engineers who got a taste for computers at work, enthusiasts eager to own any new piece of technology, or teenagers who persuaded their parents to procure the expensive and fascinating toy for them. All of them bonded over their ownership of almost unobtainable Western products and set out on a mission to overcome the lack of both hardware and information.

Outside and Inside

After users had victoriously gotten their machines home, they were faced with another problem. No software, components, or technical literature was sold in Czechoslovakia. In order to be able to fully utilise their machines, users began to meet and exchange programs and knowledge. During the era of Normalisation, it was necessary to do so with official cover of an umbrella “socialist organisation”, as was the case with almost everything at the time. Computer fans thus began to meet in the clubs of Svazarm (Union for co-operation with the army)—similarly to aviation or hi-fi fans. Svazarm's role was originally the training of youth and civilians for roles in the army; however, during Normalisation it became a de facto civilian organisation that allowed the state to monitor the leisure activities of its citizens.

Spektrum #3 1988

The task of Svazarm computer clubs was officially to “to increase the number of technical personnel, especially young people, who have good command of computers and will use it for the benefit of our national economy and for the defense of our homeland.” In reality, club-goers only did what they liked. “We didn't mind being under Svazarm and didn't care if it means something for the army and the defence of the homeland and so on. We just unscrupulously took advantage of the regime to get to the things that we were attracted to and that we liked, and that we would otherwise never get”, said one of the organisers of the local computer scene.

The vast majority of the computer clubs' activities were apolitical. Computer fans weren't in direct opposition to the regime, but neither did they support it. The American anthropologist (of Russian origin) Alexei Yurchak describes such activities with the term “vnye”, originally a Russian word that can mean both outside and inside. Such was the case of computer hobbies—they thrived thanks to a military organisation, but at the same time had relative freedom, because they were considered to be a useful contribution to scientific and technical progress.

Similarly to music or science fiction, microcomputers also became a tool for self-liberation and self-realisation. Programmer Viktor Lošťák recalls: “Back then, you were born and there was a path laid out for you. You had to be a Spark, a Pioneer, a Socialist youth, a Communist, then take part in the socialist economy, so that you have a secure life and eventually retire. There were just a few ways to deviate from this path and most of them were state organized. This was a shortcut, something that came out of the clear sky, something that nobody had anticipated. Here, you could realize your potential, you could find your talent.”

This freedom through technological accomplishments was primarily taken advantage of by men—one of the largest Czechoslovak Atari computer clubs had 1,458 members, of which only 37 were women. Even though the ratio between the numbers of men and women was more even among professional programmers, technical hobbies—and hobbies in general—were considered a domain of men.

Necessity, Rather than Choice

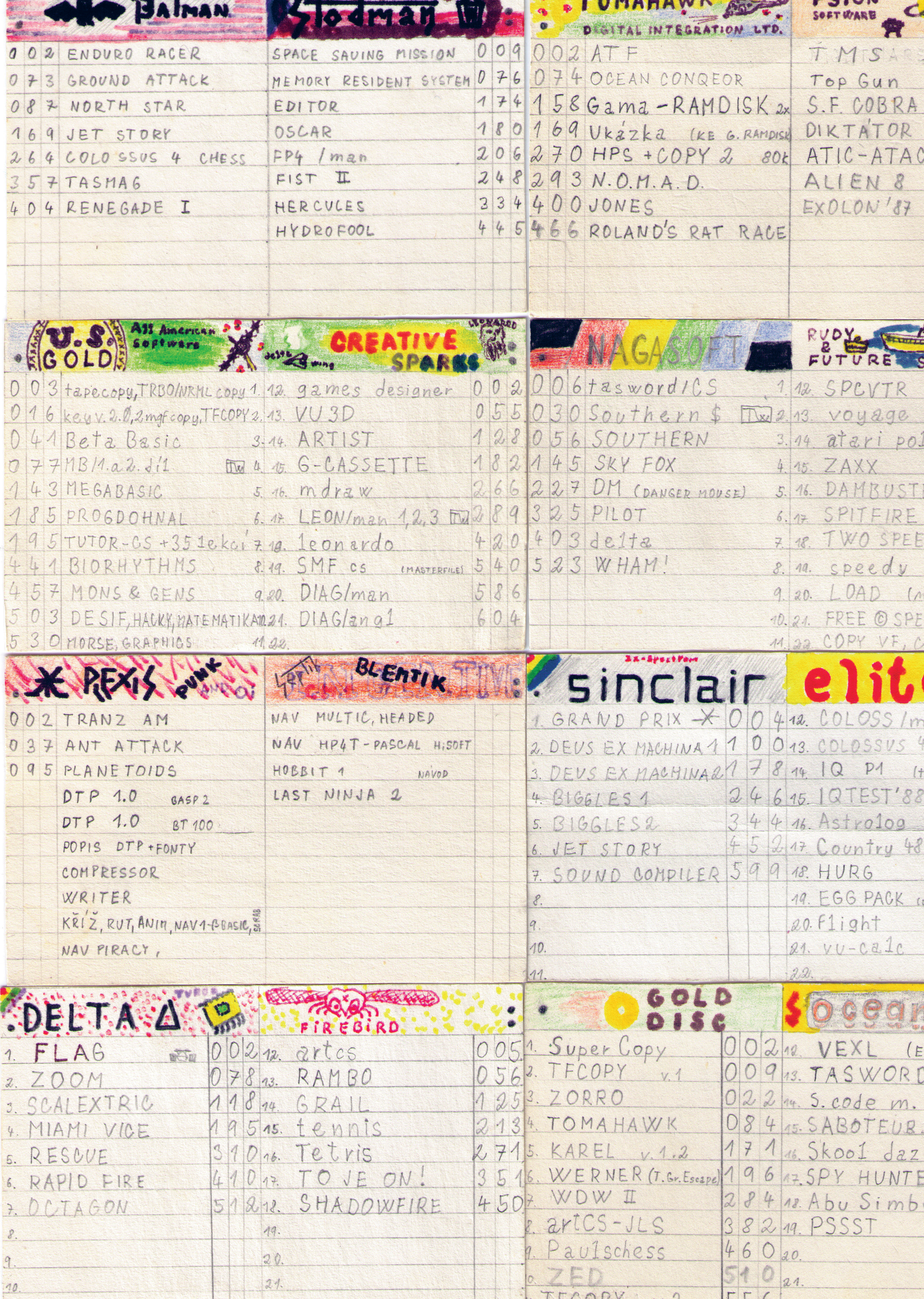

In the middle of the eighties, a number of clubs began to release printed newsletters as part of “member services.” These weren't sold publicly, but they were still printed in hundreds or thousands of copies. For most part they resembled “cookbooks” for computer gadgeteers. They published manuals, tricks, and technical descriptions, and were written mostly by other club members. Headlines such as “How to build an Atari joystick”, “The Mirek universal interface”, or “First steps in machine code” betray; they were an expression of cautious hope in “golden Czech hands”, which can keep up with technical progress despite their isolation behind the Iron Curtain.

Favourite topics were “We've read it for you” style columns, in which authors summarised findings from hard to obtain foreign magazines. Walkthroughs for games were also published. “Games are spreading throughout the exchange networks at the speed of light, but – alas – without manuals, it is not only difficult to find out the games' controls – sometimes even their very goal is obscured by impenetrable darkness”, wrote games programmer and collector František Fuka in one newsletter. Computer games of the 8-bit era were often lengthy and unnecessarily difficult.

The newsletter therefore often published so-called “pokes”; that is, modifications to a game in order to obtain a particular gaming advantage, such as infinite lives. These modifications were often made using the POKE command (hence the name), which changed the content of a particular byte in the machine's memory. Newsletter authors presented these as a triumph over malevolent authors by DIY cleverness. “Pokes” were meant to “enable all those who cannot devote all their free time to leisure to experience the sweet taste of victory”, as was stated in one of the newsletters in 1986.

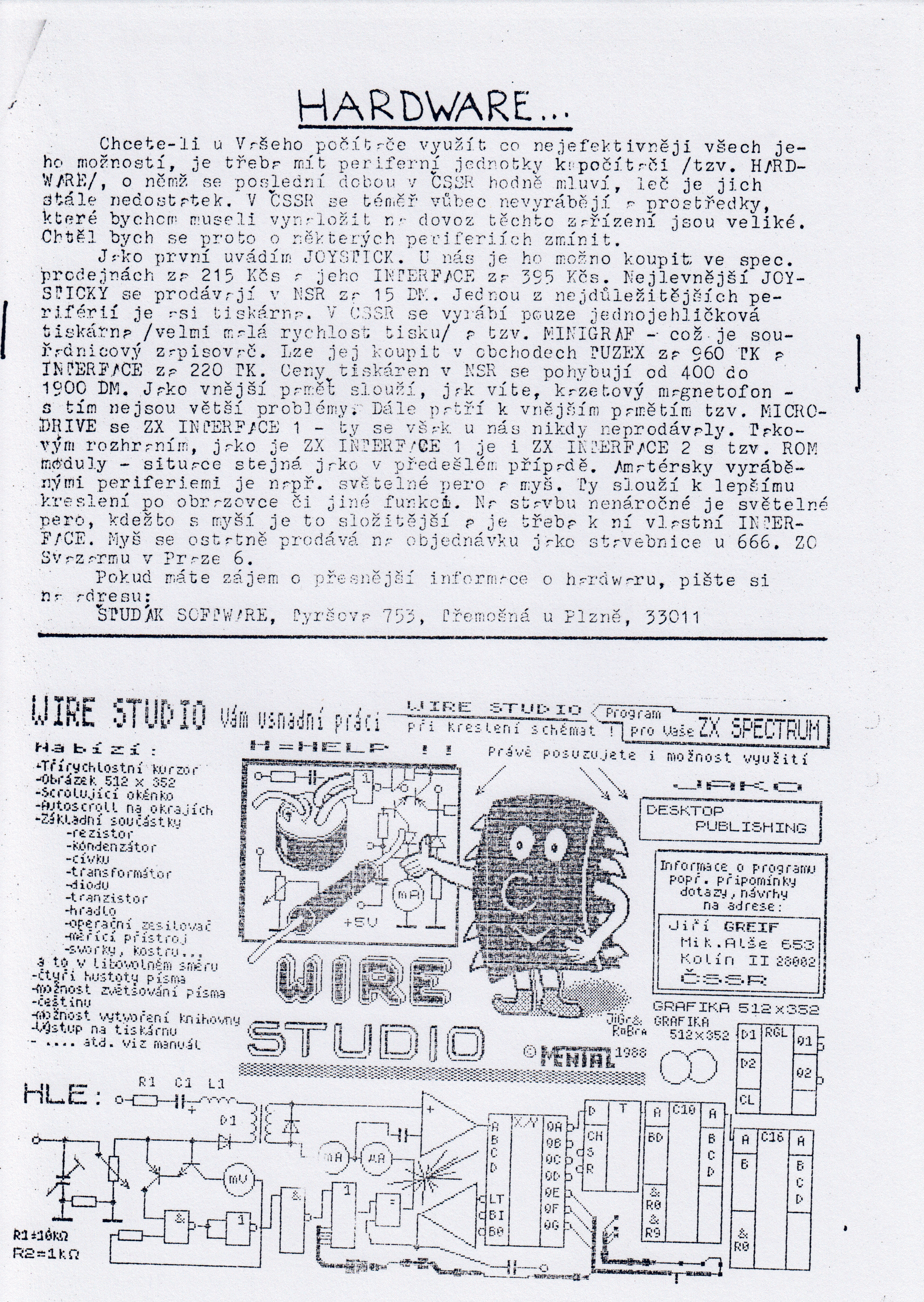

Graphic-wise, in contrast to science fiction or punk fanzines, computer club newsletters were visually and stylistically bare and pragmatic. After all, they were often written by engineers for engineers, so functionality came first. Newsletters were either typewritten of printed with dot matrix printers. Authors rarely contemplated their own mission and the political and social implications of the computer hobby. One exception was the Mikrobáze (Microbasis) newsletter, published by the 602nd division of Svazarm. Mikrobáze was led by Ladislav Zajíček, a former rock drummer and a tireless organiser of public activities, who organised concerts and video projections and published the (also internal) magazine called Kruh (Circle) in the first half of the Eighties as the head of the Young Music Section.

In Mikrobáze, Zajíček wasn't afraid to criticise the state's technological policies and “anachronic barricades laid by bureaucratic supermen.” At the same time, the world of obscure club newsletters was becoming too small for him, so he tried to run Mikrobáze in a professional manner. Starting in 1986, he had Miroslav Barták contribute his existentialist cartoons to Mikrobáze, whose geometrically precise drawings were a perfect match to the magazine's content. From 1988, Mikrobáze had a colour cover and resembled a “real” magazine. This suggests that the majority of club newsletters were published as fanzines rather than magazines out of necessity rather than conviction.

Staple and Send Out

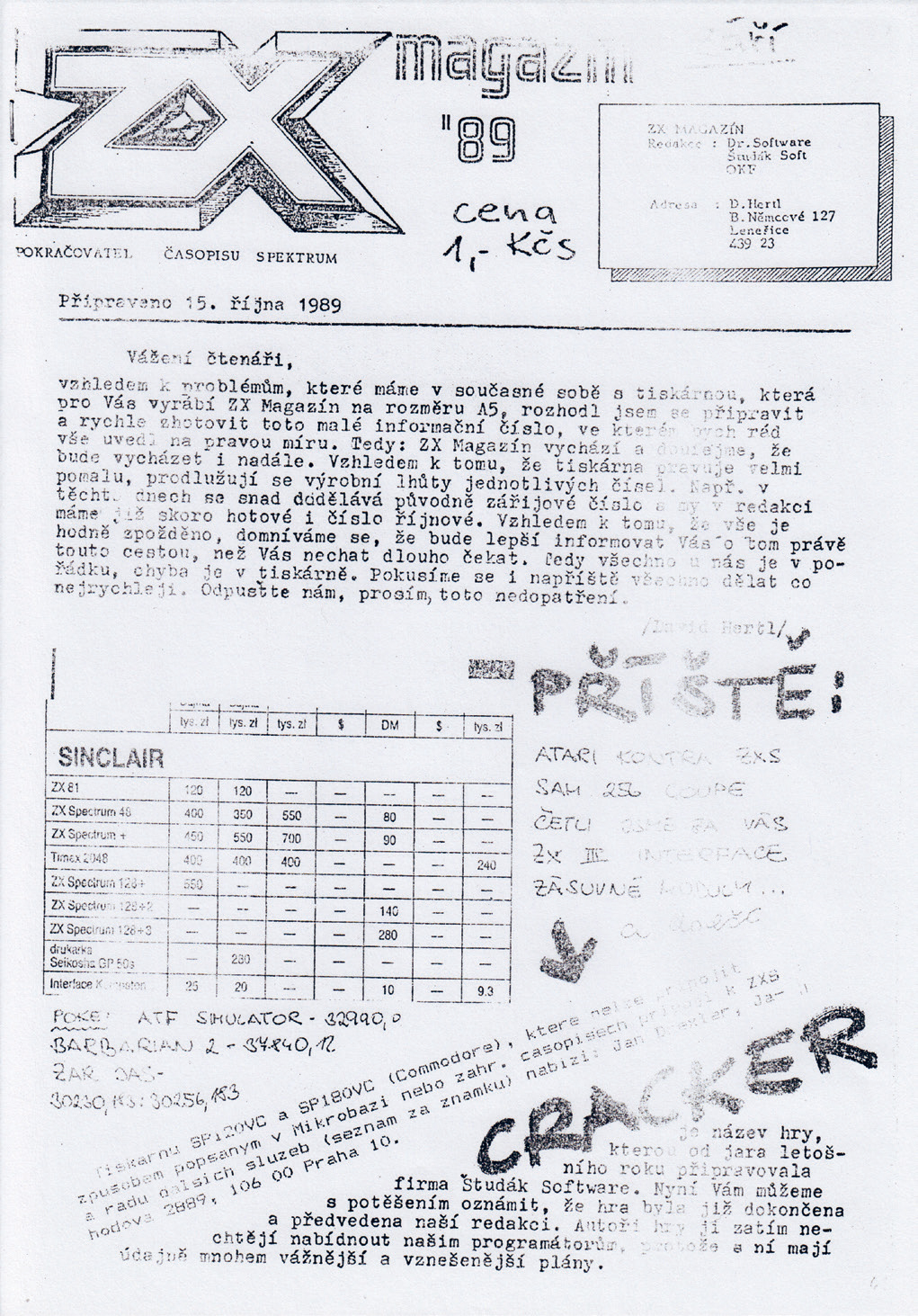

In 1988, a periodical appeared that took pride in its independence. Titled Spektrum, and later renamed to ZX Magazín, it was published in the North Bohemian town of Lenešice by the aforementioned seventeen year old David Hertl with help of his friend Ondřej Kafka. At first, he exchanged information and software with others by mail. Later, he learned of the materials and activities of Svazarm. Their club newsletters didn't impress him: “I saw an issue that had three or four blank pages, and the inscription: ‘This magazine is compiled from contributions by club members.’ That seemed embarrassing. Each editor has to be able to fill the issue himself.”

With this logic, he decided to start his own magazine. He was for the most part inspired by the Polish magazine Bajtek, which he used to get from Prague's Polish cultural centre: “We were fascinated that the Poles could have something at such a high level and we couldn't.” The first issue of the Xeroxed ZX Magazine was published June 1, 1988, and like club newsletters, the magazine was based around contributions from the fan community. People sent in their experiences with games or programs, short articles, or sent programs for review.

Hertl correspondingly thanked them on the magazine's pages: “And of course thanks to all who've sent us a program or manual—you've helped us the most. We hope to see many more of you in the next year. Because we are creating our own magazine; simply said, we're helping one another. And that's the purpose of this magazine.” Today we would call it a DIY (do-it-yourself) operation, but back then it was called “self help”. Community members even helped with the copying of the magazine. “Of absolutely amazing help was Mr. Musil from Český Krumlov, I think. He worked in a cinema where he had access to a photocopier. For about half a year, I sent him materials for the magazine. He would send me parcels with copies back; I stapled them together and sent them out”, Hertl recalls.

Originally, the magazine was sent to postal addresses obtained from other community members. The print runs rose very slowly, as Hertl was afraid of repercussions: “I was seventeen and afraid that some idiot would harass me and I wouldn't be allowed to graduate. So we kept a low profile.” Until November 1989, the print run rose from 10 to 40 copies—even though it's likely that readers reproduced further copies themselves. Publishing of the magazine was fairly risky, even in the thawing atmosphere of the late Eighties. It was effectively samizdat, or unofficial self-published literature, with no state approval or registration; it even boasted a proud sub-title of “Independent magazine of ZX Spectrum owners.”

At first glance, ZX Magazín was similar in many aspects to music or science fiction fanzines. The similarity was however mostly due to the fact that its publishers faced similar technical limitations. They only had at their disposal paper, pencils, a typewriter, glue, and (only in exceptional cases) a dot matrix printer and a Xerox machine. Unlike the editors of computer club newsletters, Hertl and Kafka tried to fit as much content on the smallest number of A4 pages, resulting in playful collages of typewritten and handwritten text and cartoons. The first true Czechoslovak computer fanzine therefore ironically had a very analogue look to it.

Complementing this graphic style, the content was similarly light-hearted, aimed not only at “engineers”, but at all types of users. It was more playful and more interactive than club magazines; the joy of using computers emanated from its pages, which is something that technical descriptions can't capture or translate. More important than the content was the feeling of reciprocity and mutuality on which ZX Magazín was based. “I had a feeling that it was fulfilling exactly the function that I wanted it to”, says Hertl, “people could begin to exchange ideas, explain something to one another, and it was important to me that they were finding one another and communicating.”

ZX Magazín was positioned on the boundary between samizdat publications and fanzines; it filled a gap on a non-existent market and its popularity rose. After the 1989 revolution, Hertl therefore immediately legalised it and started publishing it officially. His original aim of community-building grew larger than he could handle. There was such a huge amount of interest in the magazine that it wasn't possible for him to publish the magazine and study at university at the same time. He therefore handed over the publishing of the magazine in 1991 to the Proxima software company, which published it until 1994.

On the Free Market

The fate of ZX Magazín wasn't an anomaly. After 1989, many of the reasons that drew computer fans to the DIY path and to community-driven efforts had passed; programmers and journalists had professionalised. After leaving Mikrobáze, Ladislav Zajíček led the Czech version of the Amercian Byte magazine, called Bajt in Czech—a serious magazine for programmers and engineers.

On the other hand, new commercial gaming magazines such as Excalibur and later Score were launching. While not direct descendants of newsletters and fanzines, these magazines kept a subculture feel to them until the second half of the Nineties. Their approach was overtly fan-oriented: they wrote about gaming “orgies” and “ecstasies” and abounded in references to contemporary science fiction literature, cult films, and music, primarily in the electronic genres. A number of editors had an almost cult-like air around them: tens of thousands of young readers eagerly devoured each of their articles. Almost overnight, fannish writing about games became a lucrative undertaking.

Amateur computer magazines continued to be published even after November 1989, such as the Slovak Fifo magazine, or the Flop diskette magazine for fans of 8-bit Atari machines, which is still published to this day. More contemporary DIY magazines were a result of enchantment by old technology and a source of retro pleasures. Overall, they never had as large an impact after 1989 as during times of Normalisation, when they were de facto the only source of information for the fan community.

David Hertl's success with ZX Magazín led to him pursuing a journalism career. He finished his studies in history and currently works as a journalist in Czech Radio. He looks back on his DIY computer magazine as his first professional success. “There was a lot of naivete and passion in it, and it was a lot of fun”, he recalls. “I'm glad that we'd made it at eighteen—that even experienced engineers wrote to us, even though we were only young boys whose only tools were typewriters and a mailbox.”

Author´s Note

In the field of computer fanzines, I am not an innocent bystander. I co-created one, even though it was historically insignificant. In 1994, with friends from the Sušice high school, we published three issues of the printed “Occasional Computer” (Počítačový občasník), the title of which reflected our problems with meeting our deadlines. I can hardly remember why we started it back then. We were probably inspired by professional and semi-professional magazines like Excalibur that we were avid readers of; maybe we wanted to see our names in print. But most likely we were just eager to write, and computers were our number one theme. We proudly believed that people would be interested in our unfounded and adolescent opinions on which games or compression programs were best. Computers and games were an amazing and infinite world to us, in which there was always something to discover. I believe that this feeling is what also drove our more successful and more sophisticated predecessors.

—

Jaroslav Švelch (*1981) is a researcher at the University of Bergen, where he is devoted to video game monsters. His home institution is the Faculty of Social Sciences of the Charles University in Prague, where he attained a doctorate in the field of media studies. During 20072008, he functioned as guest researcher at the Comparative Media Studies department of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology; in 2012, he undertook a doctorate internship at Microsoft Research New England. Among his academic interests are digital media history, computer games, and language in an online environment. He published articles in magazines such as Game Studies and New Media & Society. His monograph, Gaming the Iron Curtain: A Social History of Computer Games in Communist Czechoslovakia, is set for publishing in 2018 by MIT Press in the USA.