A New History of Laughter in China: An Interview with Christopher Rea (Part Three)

/You draw some interesting connections between humor and other culture practices, such as amusement parks, fun house mirrors, photographic manipulations, and games, many of which speak to technological shifts in perception impacting China and the rest of the world during this period. To what degree were such devices a means of responding to the emergence of modern mass media and modernity more generally? To a great degree, I believe. During the late Qing dynasty, especially during the 1900s, you have a lot of futuristic novels that include looking devices, like the “character-examination lens,” which is a kind of moral X-ray. These writers found China’s present to be unwatchable and preferred to look ahead. In the book I include one 1909 cartoon showing a hand-held X-ray device revealing that the only thing in an elected representative’s heart is money. This 1909 “allegorical illustration” from Shanghai’s Illustration Daily uses binoculars to represent Chinese and foreigners’ tendency to view each other as either larger or smaller than life (figure below).

In the 1910s, you have the ha-ha mirror, as they called it, being installed in front of big-city amusement halls (figure below) to draw in passersby. And in 1920s films you have plenty of glasses, binoculars, windows, mirrors, lenses, and other optical devices. Not all of this play was comedic—some illustrations of flying machines from the 1880s are more fantastical than anything else—but I do see irreverence being connected to this modern mode of positive exploration, unconstrained by past ways of doing things.

Postcard of Shanghai’s Great World amusement hall (est. 1917)

To what degree did these comic genres survive the Second World War and especially the rise of Communism and the Cultural Revolution?

Big question, which I hope to answer in a future book called The Unfinished Comedy. In 1957, the prominent filmmaker Lü Ban made a film, Unfinished Comedies, in which a pair of slapstick film stars from the Republican era—Han Langen and Yin Xiucen, playing themselves (figure below)—reunite in New China. In the film, they make a trio of film comedies, only to be berated at the advance screenings by a censor called Comrade Bludgeon. Unfinished Comedies was never released and the political backlash ruined Lü Ban’s career, but fortunately the film survives, and with it the comedian’s cri de coeur.

To me, the film expresses the resilience of modern China’s comedians in trying circumstances…which are pretty much the only circumstances they’ve ever known. Each era had different constraints and opportunities, including the Anti-Japanese War (1937-45), the Civil War (1945-49), the early Mao era, (1949-65), and the Cultural Revolution (1966-76). The early Mao era, for example, ushered in a new period of didactic comedy, in which satire and eulogistic comedy were the only two modes explicitly endorsed by the Party-state. Nowadays, the government censorship apparatus is more active, and by some accounts more effective, than ever before. But all of the comic genres survive in some form, even as new genres and terminology continue to appear.

Near the end, you talk a bit about forms of internet humor in China, which you connect back to earlier examples of “crowdsourcing” jokes for Chinese publications. To what degree were the styles of humor you identify a popular or grassroots phenomenon as opposed to one reserved to the literary elites? To what degree do you see contemporary web culture as introducing a new “age of irreverence” into China? Well, people who could read and write were in the minority in China at the turn of the twentieth century. I did come across a few joke books compiled by scribes working with illiterate comic performers. But with the exception of amusement halls, photographs, and films, most of the types of humor I discuss are written, and thus were to some degree products of “elite” culture.

Of course, the Chinese literary sphere had its own pecking order. Most of what I would consider to be the best humor writers of the Republican era were scholars of the Chinese tradition as well as multilingual and cosmopolitan—writers like Lao She, Zhou Zuoren, and Qian Zhongshu. The “humor movement” of the 1930s was an elite one that ended up getting some traction in popular culture, and it’s the moment scholars know best. I make a point of also spending some time with the hacks, the amateur enthusiasts, and the entrepreneurs.

You once talked about “Web -10.0,” referring to earlier iterations of participatory culture—people using mini presses to publish ‘zines in the 1850s, amateurs staffing their own radio stations in the 1920s, and so on. An entrepreneurial ethos also developed in China ca. 1890s-1930s, which involved a lot of sharing. Tabloids, literary journals, cartooning magazines, and small film companies shared labor—moonlighting was the norm—and content, like jokes.

Xu Zhuodai, who became one of Shanghai’s most popular comic writers, founded a slapstick film company in 1925 with a second-hand camera and a bunch of buddies from his theater troupe (figure below). He called their opportunistic, shoestring approach to the business “cigarette butt-pickup-ism.” Wu Jianren, one of the most prolific joke-writers of the 1900s, claimed that people in Shanghai, Hong Kong, and Southeast Asia kept retelling his jokes. So he republished his favorites. Cartoonists were even more welcoming of new talent, and solicited contributions from readers.

A still from Cupid’s Fertilizer (1925), produced by Xu Zhuodai’s Happy Film Co.

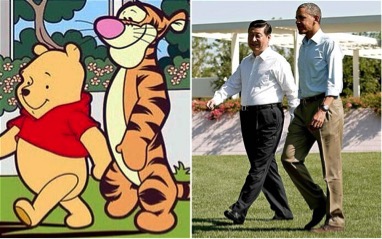

My impression is that, as a whole, Republican Chinese humor, while relentlessly exploratory, was still nowhere near as egalitarian as contemporary web culture, if only because of the breadth and speed of access today. I’ve written before about online video spoofs known as e’gao or kuso, which became popular in the mid-2000s, and generated the most famous comic Chinese meme, the Grass Mud Horse.

I do think that the web has facilitated a new virtual age of irreverence in China (figure below). But the authorities have a chokehold on print publishing and mass media, so, at the moment, we’re hearing much less laughter out of China than we should.

Christopher Rea is an associate professor of Asian studies and director of the Centre for Chinese Research at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver. He is author of The Age of Irreverence: A New History of Laughter in China (California, 2015); editor of China’s Literary Cosmopolitans: Qian Zhongshu, Yang Jiang, and the World of Letters (Brill, 2015) and Humans, Beasts, and Ghosts: Stories and Essays by Qian Zhongshu (Columbia, 2011); and coeditor, with Nicolai Volland, of The Business of Culture: Cultural Entrepreneurs in China and Southeast Asia. He is currently translating, with Bruce Rusk, a Ming dynasty story collection called The Book of Swindles.