In Search of Indian Comics (Part Two): The Politics of Indian Comics

/Today, I continue to narrate some of my adventures in search of a better understanding of comics and graphic novels in Contemporary India. Last time, we considered the ways that contemporary artists are building upon India's folk art and mythological traditions. I ended with some reference to the importance of Amar Chitra Katha, a publisher that for some decades produced comics teaching Indian boys and girls about their legends and history. These comics helped to establish the public's expectations about what a graphic novel from India might be like. I also discussed Bhimayana: Expereicnes of Untouchability, which depicts incidents in the life of Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar, a civil rights leader who spoke on behalf of the Dalit people: this book taps the folk art traditions of the Gond people, as well as seeking to tell aspects of Ambedkar's life that are traditionally left out of the history books about the founding of the Indian nation, where Ambedkar is mostly known as the author of the country's constitution. Aparajita Ninan, part of the group of graphic artists who joined me in Dehli's Crafts Museum, worked on Bhimayana. She's best known for her work on A Gardner in the Wasteland: Jotiba Phule's Fight for Liberty, written by Srividya Natarajan (one of Bhimayana's two co-authors) and also published by Navayana Press. Phule was another important critic of the caste system in India who wrote a key book -- Slavery (Gulamgiri) in 1873 -- who challenged Brahmanism and critiques the enslavement of the "lower" castes, a work inspired by and dedicated to the Abolitionist movement in the United States. Many of Phule's ideas remain controversial to the present day, including his sharp critiques of the ways that the Hindu tradition was structured to insure that the Brahmin caste continued to dominate over everyone else. Ninan's art is rendered in an inky black and white style that has the brute force of agit-prop. She draws imagery and symbols from around the world in part to link Phule's arguments back to their historical roots, including his intense engagement with American abolitionism and the French revolution. Here, for example, is a two page spread which links Phule to a range of other freedom fighters and Civil Rights leaders from around the world and across history, all of whom marched, the books argues, behind the cause of Liberty, Fraternity and Equality.

Another spread compares the brutal techniques deployed to keep the castes in place with the role that lynching in the deep American south.

And this page sums up the contrasting perspective that Phule brought to Hinduism.

Keep in mind that the current government actively promotes Hindu nationalism and conservative ideology and takes a dim view of those who critique or challenge those traditions.

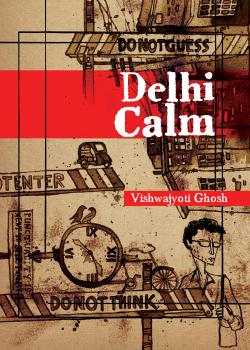

Vishwajyoti Ghosh, another member of our little gathering, is the author and illustrator for Delhi Calm, a graphic novel about a group of rock musicians touring the countryside, and what happens when Indira Gandhi declares a national State of Emergency and imposes martial law on India. Or perhaps not. The book works hard to establish a state of plausible deniability: "Nothing like this ever happened. If it did, it doesn't matter any more, for it was of no interest or relevance even while it was happening. Any resemblance to persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental. This is a work of fiction. Self-Censored." The female dictator is described throughout only as Little Moon; her supporters are often depicted wearing happy masks, implying that a forced smile is really the only safe way to respond to the political turmoil that surrounds them.

Signs of propaganda, police violence, and political imprisonment run across the book, often in the background of panels. Paranoia infuses every social interaction in a world where the rights of citizens have been suspended and no one knows what is going to happen next. As an American reader, trying to process it with the help of Wikipedia entries, I did not get all of the layers of allegory and allusion here, but the work was nevertheless compelling.

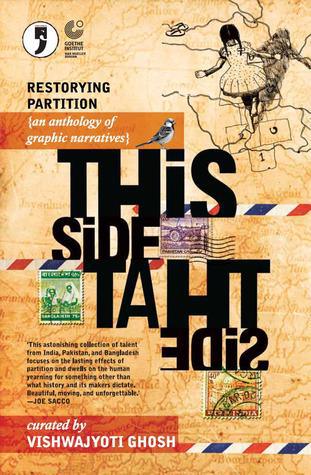

Ghosh also curated an important anthology of "graphic narratives", This Side That Side?: Restorying Partition, convening a diverse range of South Asian artists, writers, illustrators, filmmakers, and other storytellers, to reflect on the political forces that separated off India and Pakistan. Ghosh writes in the book's introduction:

"Restorying Partition can never be easy. If one wants to avoid the usual revival of Mass Memory, one has to look beyond those maps lodged in our nervous systems that make nervous headlines on our televisions. To listen to the subsequent generations and the grandchildren and how they have negotiated maps that never got drawn. This Side, That Side is a tiny drop in the river of stories that must be told before the markers run dry."

The range of perspectives and techniques included makes its own political statement. Nina Sabnani, an animator, tells the story ("Know Directions Home?") of her family's displacement using stitch work, a technique she also deploys with great effect in her animated film, Tanko Bole Chhe (The Stitches Speak).

Malini Gupta and Dyuti Mittal contributed "The Taboo," adopting a visual style that engulfs the page in intertwined art rather than break it down into panels.

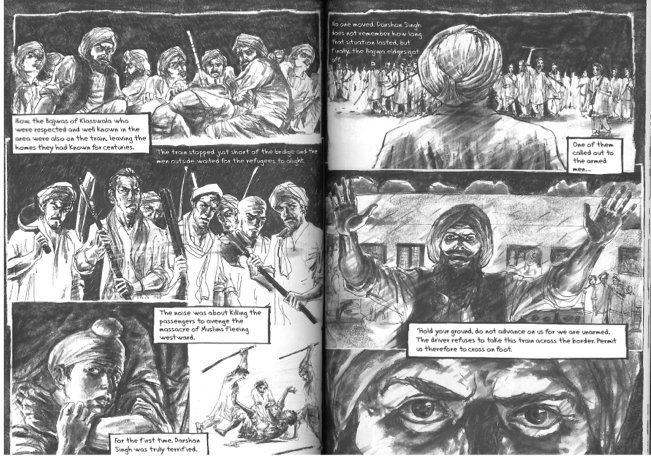

"I Too Have Seen Lahore!", a collaboration between Salman Rashid (in Lahore) and Mohit Suneja (in Delhi), conveys some of the horrors and brutality of this historical upheaval.

The following comes from my travel diary:

After our lunch with the comics artist at the Crafts Museum, my host Parmesh Shahani takes us to Hauz Khas Village (which locals tend to call HKV or simply the Village). It is hard to describe the vibe of this place. On the outskirts there are dozens of little food stalls and carts, each selling street food, and a constant zip of the motorcycles and autorickshaws, which we have seen everywhere on this trip. As we pass through the gates, and past a local deer park, we enter an environment which represents a series of temporal and cultural layers. The original layer are ruins, going back to the 11th century (or there-abouts) of what was once a great Islamic university and a cluster of palaces. Much remains left behind – buildings with huge domes, crumbling columns, decaying steps, which stretch out for as far as the eye can see. Amidst them, people are sitting and having the street food, playing games with balls and rackets, posing for selfies, and otherwise getting on with the business of life.

On top of this was built an urban village – traditional houses and shops which could have been built at any point in the 20th century. We later learn that this area was a kind of criminal underworld in the early 20th century – a tribe of bandits were located here and the city constructed walls to keep them away from the rest of the population, assuming anyone who ventured into this space knew what they were getting themselves into. This is what gives the area its thuggish charm. And now, the area is undergoing a process we might describe as gentrification: it got discovered by hipster youth and has been transformed into their playground. So, they have built, without building permits in most cases (Parmesh says), cute little clothing stores, poster shops, record stores, bakeries, coffee shops, and night clubs, on top of the structure of the older village, often in a very ramshackled or haphazard fashion.

It’s dusk and music is already blarring out of speakers all around us. We pass young people with eccentric hairstyles and cool clothes, doing some early evening shopping, and looking forward to an evening of clubbing. We see more white youth than we’ve seen elsewhere – and almost all of them are wearing traditional Indian clothing – while the Indian youth are almost all wearing western garb. (I wonder if either notices that their cultural fantasies are not exactly aligned here.)

The whole effect is something from a cyberpunk novel – Neo-Delhi rather than Neo-Tokyo, with a healthy amount of the kipple and chaos of something like Blade Runner. Parmesh shares with us a few of his favorite shops including a really cool poster shop which has all kinds of brightly colored vintage paper products: I want, but there’s not enough time to look and process. As we are leaving, though, the manager gives us a business card and says you can order online and he will ship to the U.S. Big smiles.

And here, as elsewhere across India, there is spectacular street art, itself suggesting the graphic storytelling potential of this amazing country.

Next Time: Where, oh where, can you find comics in India?