Engaging with Transmedia Branding: An Interview with USC's Burghardt Tenderich (Part Three)

/What do you see as some of the ethical concerns that transmedia branding practice pose for industry leaders? Are there times when transmedia’s blurring of the boundaries between fact and fiction, for example, can be misleading or may cross established policies regulating trade practices? Like any other forms of marketing or branding, transmedia storytelling raises ethical considerations, some of which are not all that different from those that apply to any marketing discipline. Edward Bernays, considered by many to be the ‘father of public relations,’ was led the charge in applying the principles of political propaganda to marketing communications.

During the boom years following World War II, supply for many products and services suddenly exceeded demand, so Bernays and his contemporaries on Madison Avenue, on behalf of their industrial clients, built PR campaigns with the sole purpose of creating demand for things people had previously no idea they wanted. This was the birth of consumerism – based on the assumption, held by Bernays and others, that the masses are stupid and easily manipulated. I’m afraid we see a lot of this approach still today in the worlds of marketing, advertising and public relations.

More specifically to the ethics of transmedia is whether fictional storylines can be mistaken for reality in campaigns where the lines are blurred. Due to the prevalence of sarcasm, parody and humor in storytelling, the ethical standard is not as much determined by the literal truth of campaign content, but whether or not it is—or has the potential to be—deceiving. The notion of deceit is central to the discussion of transmedia branding because of one of the discipline’s key characteristics: many transmedia branding campaigns purposefully mix fiction with reality and playfully expose participants to a constant back and forth between the two.

The question is whether ethical boundaries are surpassed when brands use fictional content mixed in with actual events. For example, the campaign Art of the Heist stages a fake break-in into the Audi car dealership where actors shatter the store front window to steal an Audi A3. This is the kick-off to an online and offline transmedia campaign to solicit attention to the A3’s launch. The day after the theft, at the New York auto show, instead of seeing America’s first A3, attendees saw signs reporting the missing car. What if this campaign scared people in the real world? While we assume that most people can distinguish between fiction and reality here, some may not be able to.

Another form of ethical transgression is appealing to emotions in order to divert attention from distorted facts. This was masterfully done in Chipotle’ Scarecrow video, one of the most impressive examples of world building. The animated video shows a scarecrow who witnesses the unappetizing side of industrial food production and decides to ‘go back to the start’ by farming and selling organic vegetarian produce, including the red chili pepper from the Chipotle logo. The problem is that Chipotle’s food is not vegetarian and, at the time of the video release, mostly not organic. This triggered internet video publishers Funny or Die to extend the storyline with a brand jam: they recorded a video using the original footage and soundtrack, but imposed subtitles and changed the lyrics to expose Chipotle’s ethical transgressions.

You point to growth hacking as representing one future direction for communication strategy. How are you defining this concept and what are some examples of the ways this has worked to increase the visibility of brand messages?

Growth hacking represents principles and techniques designed for rapid adoption of a brand. Communication strategy is part of this, but growth hacking is a broader concept that includes product design and refinement as well as programming. It’s frequently used to promote web sites and consumer technologies, but its potential use is much broader. The basic idea is that a product or service is defined jointly with its intended users, mainly by soliciting feedback, analysis of user data and constant A/B testing. The communication strategies focus on spreadable or even viral components.

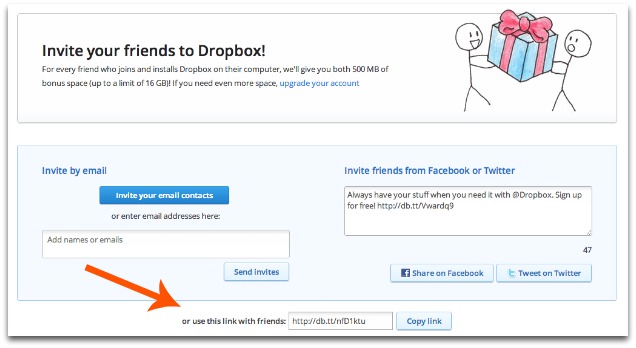

To illustrate, the original growth hack was Hotmail’s decision to print underneath each email the tagline “Get your free email at Hotmail.” At a time when free email accounts were unheard-of, this led to truly viral adoption of the new tool. Dropbox used a similar growth hack by setting up a member referral system for free cloud storage.

But the technical co-founders of Dropbox also demonstrated their impressive PR instincts by using communication growth hacks. For example, in order to recruit highly technical beta users, company founder Drew Houston posted a short video on Digg. The video was laced with hidden messages and jokes that only experienced software developers would understand. Called “Easter eggs” in developer lingo, these messages included references to Chocolate Rain, the movie Office Space and keys for decrypting Blu-ray disks. This nod to its technical audience helped the video rise to the top of Digg. This particular strategy – described in the Harvard Business School case on Dropbox – points to one of the key differences between mainstream PR and growth hacking: it’s about reaching the right people, not the maximum number of people.

Growth hacks can also be based on simple creative ideas, such as Apple’s decision to ship iPods and later iPhones with white headphones, so people in the street would know the person who just walked by wasn’t just listening to music on any mp3 player or smartphone, but indeed an Apple product. Apple also strategically featured the white headphones prominently in all its ads and commercials

And, of course, people created funny parodies, like the one below with the Spong Bob silhouette, when the iPhone 5 was launched.

Interestingly, while I was sitting at a window on the second floor of a café just outside an outdoor mall on Black Friday recently, I couldn’t help noticing that almost every other female shopper was recognizably carrying either a Lululemon or Victoria’s Secret bag. From my perspective, they were swarming constantly in every direction of the shopping area, serving the unintended function of brand ambassador.

Also, this summer we took a family trip to Berlin. The streets right around the Brandenburg Gate were packed with taxis that all prominently displayed the same ad, for Uber (!)

Berlin has banned Uber, which makes this form counter-cultural (commercial) activism even more noteworthy.

In summary, growth hacking comes in many flavors that pertain the central goal of creating engagement with a brand.

Burghardt Tenderich is a Professor at the University of Southern California Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism in Los Angeles, CA, where he teaches and researches about strategic communication, transmedia branding, emerging media technologies and media entrepreneurship. He is the author of Transmedia Branding (2015) USC Annenberg Press, together with Jerried Williams. Burghardt is Associate Director of the Annenberg School’s Strategic Communication and Public Relations Center, and co-author of the Generally Accepted Practices for Public Relations (GAP VII).

Burghardt has over 20 extensive experience in communication and marketing in the information technology and internet industries and he holds an M.A. and a Ph.D. in Economic Geography from the University of Bonn, Germany.