Wandering Through the Labyrinth: An Interview with USC's Marsha Kinder (Part Three)

/I was struck in 1999 by your effort to also create a space where artists working in the museum and gallery space were engaging with game designers working in more commercial contexts. This dimension seems to have dropped out of the Transmedia Frictions book altogether. What does this suggest about the continued roles of cultural hierarchies in the realms of digital art and theory? When we planned the Interactive Frictions conference, we wanted to be as broad and inclusive as possible, which meant including games. I had hoped someday to finish the Runaways game as a Labyrinth project, once we had sufficient grant support and more sophisticated programmers. It was not that we looked down on games as unworthy of critical and cultural attention, but rather that we simply didn’t have the resources to do a first rate job.

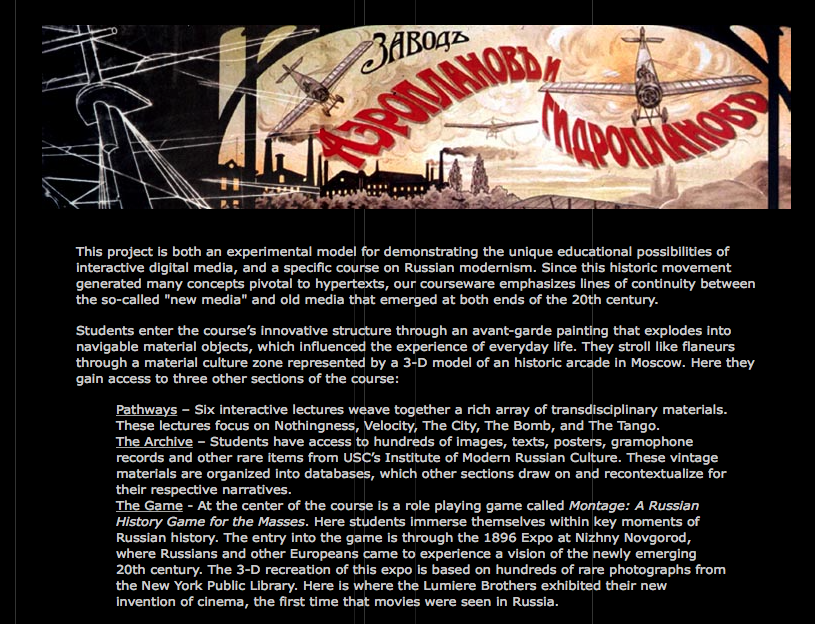

We made a stab at it in our on-line courseware project, Russian Modernism and Its International Dimensions, an archival cultural history which unfortunately we never finished—even though we had the assistance of Jenova Chen, the most successful student to emerge from USC’s Interactive Media Division; a grant from NEH; and first-rate Slavic Studies scholars (Yuri Tsivian on film, from University of Chicago; Olga Matich on literature, from UC Berkeley; and John Bowlt on visual culture, from USC). Set at the 1896 Russian Expo in Nizhni Novgorod (where cinema was first screened for the Russian public and where the Tsar and his court were in attendance), this project provided students with three ways of engaging with these historical materials.

They could explore a virtual 3-D model of the Expo and its pavilions, where they could play a game called Montage: A Russian History Game of the Masses.

The game enabled them to engage with experimental art, subversive politics, or new technology—the three forces that made modernism so distinctive in the Russian context.

Or, they could visit GUM, (Glavnyi Universalnji Magazin), the “main universal store” in Moscow’s red square from the 1920s, whose innovative glass-roof design was also featured at the 1898 Expo. Like consumerist flaneurs strolling through a modernist arcade, here students could stop at several shops, each presenting an illustrated interactive lecture on a range of topics (e.g., nothingness, velocity, the bomb, the expo, St. Petersburg: the novel and the city, etc.) by leading scholars both from the U.S. and Russia.

Or, they could visit the archive in GUM’s basement, an extensive database of artworks that students could use in their own projects. Since the courseware was not finished, students were invited to help build the rest of it, as if they were constructionists, learning by doing. The project was designed to show how aesthetic concepts from Russian modernism (such as, dialectic montage, constructionism, and synaesthesia) are still useful in developing our own era of digital multimedia. The basic conception is still sound and challenging, but we don’t have the resources to produce it.

By the time we published Transmedia Frictions, the academic world of game studies had already developed its own trajectories. Of course, there were exceptions like Bill Viola (who attended the original Interactive Frictions conference and had an installation in our IF exhibition). Later, in collaboration with specialists in our Interactive Media Division, he developed a game about a journey of Buddhist enlightenment. Although he originally proposed a collaboration with Labyrinth, we didn’t have the resources to develop it at the time. We were moving in the opposite direction toward museum installations, particularly because we had had such a difficult experience with the Montage game at the heart of Russian Modernism.

There's a recurring interest throughout the essays, in both parts of the book, in issues of cultural memory, the archival, and the documentary. What new models have emerged over the past decade for thinking about the relationship between the digital and our collective understandings of history?

One of the new models that has emerged over the past decade is the genealogical search for family and cultural roots. We can find it in the growing popularity of a website like ancestry.com and in the television shows hosted by Henry Louis Gates, Jr., African American Lives (2006) and Finding Your Roots (2012), where he helps celebrities discover the truth about their roots. We can also see it in the current fascination with Selfies and with the impulse to upload your own home movie fragments on YouTube. And one can also find it in new works on home movies—in a marvelloous book like Patricia Zimmerman’s Mining the Home Movie, and in the extraordinary films of Hungarian media artist Péter Forgács.

In 2000, Labyrinth embarked on a collaboration with Forgacs to turn his sixty-minute, single-channel film, The Danube Exodus, into a large scale, multiscreen, immersive installation, which opened at the Getty Center in 2002 and continued to travel worldwide until 2012. It was one of our three projects in the “Future Cinema” show, and is discussed by Stephen Mamber in the anthology. Largely as a result of this exhibition, Forgács received the prestigious Erasmus Award, for an artist in any medium who has made an exceptional contribution to culture in Europe and beyond.

Having been aired on European television in 1997, Forgács’s film provided intriguing narrative material: a network of compelling stories, a mysterious river captain whose movies remain unknown, a Central European setting full of rich historical associations, and a hypnotic musical score that created a mesmerizing tone. Now that we had 40 hours of footage to draw on, there was an intense struggle for narrative space: between the European Jews who were fleeing the Third Reich in 1939, attempting to get a ship in the Black Sea to take them to Palestine; and the German farmers who were returning home to Germany in 1940 after the Soviets had confiscated their lands in Bessarabia; and the Hungarian river captain who ferried both groups into history by documenting their journies on film.

As in Forgács’s other films, the home movies enriched or contradicted what we thought we already knew about history. Sometimes the home movie footage was juxtaposed with excerpts from official newsreels, but it always introduced an alternative vision. To see the fragile home movie footage displayed on television is one thing, but to see it projected in a museum on five large screens (each 6ft x 8 ft) is something else. This is the way superheroes or villains (like Napoleon or Hitler) are usually displayed, not domestic home movies with their humble characters and banal events.

This collaboration was the first time Labyrinth had actually designed an installation from the get-go—as opposed to making a DVD-ROM that was later included in a museum exhibition. Of course, there were several DVD-ROMs included in the show, plus a related website (produced by a group in Europe), and a related exhibition of maps and artifacts from the Getty Collection. We began to think of this work as a “transmedia network,” one that linked several spaces and many collaborators together.

Intrigued by the use of vintage home movies and the richness of what could be gleaned from their visuals and physical gestures, we were inspired to do another transmedia network for our next project. Titled “Jewish Homegrown History: Immigration, Identity and Intermarriage,” it consisted of a museum installation which premiered at USC in October 2011 as a Vision and Voices event

and then ran for several months in 2012 at the Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles. The exhibition featured three large screens, even larger than those we used in The Danube Exodus, on which we projected home movies of Jews living in Los Angeles.

There was also a bank of computers with the website, which enabled users to upload their own family stories and photos and to hear histories of others. The home movies displayed on the large screens and the website all addressed the subthemes of immigration, identity, and intermarriage, which were also emphasized in quotations that were posted on the walls. Mainly derived from 8mm and Super 8 footage, the home movies were collected in a series of “home movie collection days,” which enabled us to form productive collaborative relations with those contributing the footage.

After interviewing members of the family, we edited the footage and added sound. In the exhibition space we also screened a series of short documentaries about Jews in Los Angeles, a display that evoked a comparison between these two forms of non-fiction.

Both of these installations made me think of Patricia Zimmerman’s inspiring statement, which was prominently displayed on the walls of the exhibition: “Amateur films urge us all—scholars, filmmakers, archivists, curators—to re-imagine the archive and film historiography. They suggest the impossibility of separating the visual from the historical and the amateur from the professional.... We need to imagine the archive as an engine of difference and plurality, always expanding, always open.”

Marsha Kinder began her career in the 1960s as a scholar of eighteenth century English Literature before moving to the study of transmedial relations among narrative forms. In 1980 she joined USC’s School of Cinematic Arts where she continued to be an academic nomad, with narrative as her through-line. Having published over one hundred essays and ten books (both monographs and anthologies), she is best known for her work on Spanish film, specifically Blood Cinema (1993); children’s media, especially Playing with Power in Movies, Television and Video Games (1991); and digital culture (including her new anthology Transmedia Frictions: The Digital, The Arts and the Humanities (2014), co-edited with Tara McPherson. She was founding editor of innovative journals, such as Dreamworks (1980-87), winner of a Pushcart Award, USC’s Spectator (1982-present) and since 1977 served on the editorial board of Film Quarterly. In 1995 she received the USC Associates Award for Creativity in Scholarship, and in 2001 was named a University Professor for her innovative transdisciplinary research.

In 1997 she founded The Labyrinth Project, a USC research initiative on database narrative, producing award-winning database documentaries and new models of digital scholarship. In collaboration with media artists Rosemary Comella, Kristy Kang and Scott Mahoy, and with filmmakers, scientists and cultural institutions, Labyrinth produced 12 multimedia projects (DVD-ROMs, websites, installations and on-line courseware) that were featured at museums, film and new media festivals, and conferences worldwide. Kinder’s latest work, Interacting with Autism, is a video-based website produced in collaboration with Oscar-winning documentary filmmaker Mark Jonathan Harris and Scott Mahoy. Since retiring from teaching in Summer 2013, Kinder is now writing a new book titled Narrative in the Era of Neuroscience: The Discreet Charms of Serial Autobiography.