Wandering through the Labyrinth: An Interview with USC's Marsha Kinder (Part One)

/In 1999, the University of Southern California hosted the Interactive Frictions conference, organized by Steve Anderson, Marsha Kinder and Tara McPherson, with participants including some of the leading digital theorists, artists, and game designers of the period. Among those featured were: Edward Branigan, Justine Cassell, Anne-Marie Duguet,Katherine Hayles, Vilsoni Hereniko, Henry Jenkins (that's me!), Isaac Julien, Norman Klein, George Landow, Brenda Laurel, Erik Loyer, Peter Lunenfeld, Lev Manovich, Patricia Mellencamp, Pedro Meyer, Margaret Morse, Erika Muhammad, Janet Murray, Michael Nash, Marcos Novak, Randall Packer, Mark Pesce, Vivian Sobchack, Sandy Stone, Yuri Tsivian and many others. I speak at many conferences each year, but this remains in my memory a defining event in terms of my own thinking about digital media and a conference where I met a whole bunch of folks who I have ended up working with over the past decade and a half. For me, the conference brings back memories of the launch of the MIT Comparative Media Studies Program, which I was able to discuss in my remarks at the event, and also represents the first of a series of interactions with the USC faculty that led ultimately to my decision to move here almost six years ago. Last year, Kinder and McPherson revisited this conference with a new book, Transmedia Frictions: The Digital, The Arts, and the Humanities, which brought together many of the original participants, who shared essays that built upon, but also artfully revisited, their original contributions at the event. The result is a great opportunity to reflect on the evolution of the digital arts and humanities across the intervening years, allowing us to test our original impressions and to reformulate them in response to so much that has happened since.

A key signal about what has changed is reflected in the title of the book -- a movement from a focus on interactivity to an emphasis on transmedial relations. Here, Marsha Kinder is reclaiming a term she introduced in her 1993 book, Playing with Power in Movies, Television and Video Games: From Muppet Babies to Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. Asked to write a blurb for this collection, here's what I had to say: “As someone who attended and participated in the 1999 Interactive Fictions conference, which in many ways consolidated more than a decade of theorizing about and experimenting with digital media, I was uncertain what to expect from Transmedia Frictions. What I found was a rich collection that looks both backward to reconstruct the paths not taken in digital theory and forward to imagine alternative ways of framing issues of medium specificity, digital identities, embodiment, and space/place. This collection is sure to transform how we theorize—and teach—the next phases of our profound and prolonged moment of media transition.”

Few scholars are better situated to reflect on those shifts than Marsha Kinder, who was among the first in cinema studies to embrace digital tools for presenting her scholarship and who has overseen some remarkable collaborations with leading creative artists over the past decade through the Labyrinth project. She has been a friend and mentor across these years, someone who was always leading the charge and inspiring younger scholars to think about new ways of doing and presenting scholarship, and someone who has bridged between theory and practice in bold new ways. Our work has been complexly entangled through the years, given our shared interests in children's culture, transmedia, games, and digital humanities. What began as an interview about her new book has turned into an amazing retrospective on her body of work in the digital humanities, which, true to her vision, is presented here in a multimedia fashion.

I will be following up this interview with Marsha with a second interview with her co-editor Tara McPherson, who has also been a friend and collaborator of mine over the past two decades.

Tell us about the 1999 Interactive Fictions conference. What were its aims? What do you see now, looking backwards, as its historical importance in the development of digital art and theory? How did it inform your own subsequent works in this area?

In 1997, I was asked by USC’s Annenberg Center to direct a research initiative that would explore the potentially productive relationship (rather than rivalry) between cinema and the then-emerging digital multimedia. I saw this transmedia focus as an opportunity to combine the immersive and emotive power of cinema with the interactive potential and database structure of new digital forms.

Although I had already developed my concept of database narrative, I was just beginning to engage in production myself, making companion works for my two most recent books. For Blood Cinema, my book on Spanish cinema, I collaborated with my doctoral student Charles Tashiro on making the first scholarly interactive CD-ROM in English language film studies, which led to a bilingual series called Cine-Discs.

And, for Playing with Power in Movies, Television, and Video Games, I collaborated with another grad student (Walter Morton) on a video documentary showing kids interacting with Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles.

When I asked one of the kids in the arcade why they couldn’t play as April O’Neil, he said, “That’s the way the game is made!” Of course, he was right. And that made me want to make my own feminist game on gender.

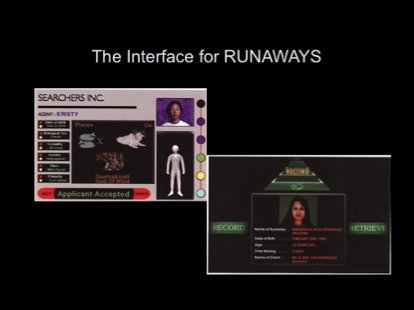

The next step was making a prototype for an experimental electronic game called Runaways...

which I co-wrote, co-produced and co-directed with documentary filmmaker Mark Jonathan Harris and which you, Henry, kindly featured at your conference on Gender and Computer Games at MIT and in your anthology, From Barbie to Mortal Kombat.

Those projects enabled me to become the founding director of The Labyrinth Project, and to decide it would function both as a research initiative generating new theory and as an art collective making works that would advance the creative potential of the new digital media.

But to do this, I needed to quickly assess what had already been done and what was still emerging both in theory and practice. I also needed to find the most productive collaborators, and to discover which issues were driving the cultural debate and generating the most “friction.”

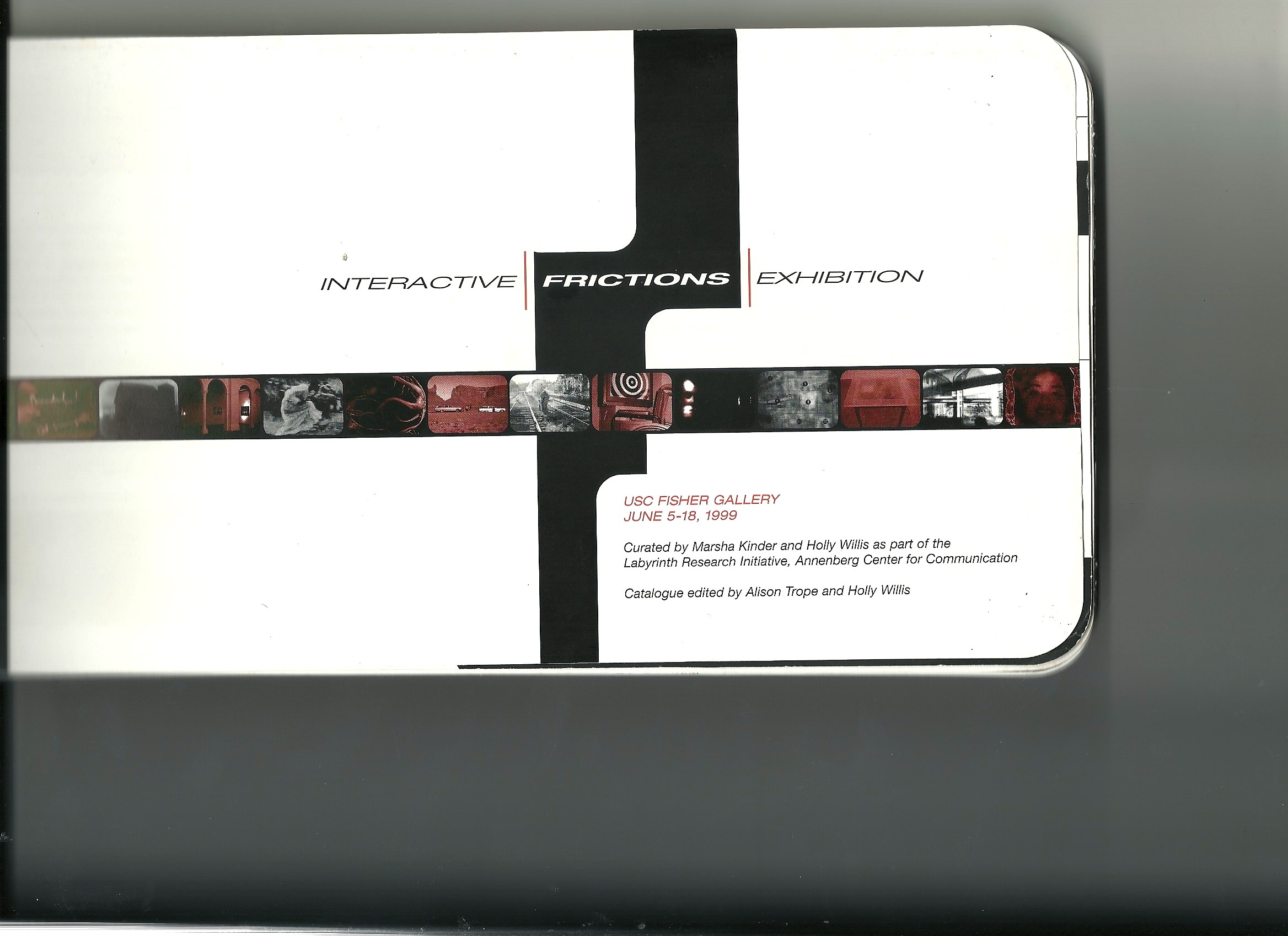

Being an academic, I decided the best way to perform that quick assessment was to host an international conference. Calling it “Interactive Frictions,” I knew it had to be very inclusive—with filmmakers, photographers, installation artists, animators, game designers, programmers, theorists, critics, cultural historians, curators, media scholars, and entrepreneurs. And because its scope was to be so expansive, I definitely needed innovative collaborators to help run the events. So I asked my colleague Tara McPherson and our graduate student Alison Trope to be my co-hosts at the conference, Holly Willis to co-curate the exhibition, and Steve Anderson to write the program. To emphasize the creative energy emerging from these new combinations as well as from their historical precursors, the conference was intentionally structured like a three-ring circus, featuring not only keynote speeches, live performances, and scads of panels but also a group exhibition in the Fisher Gallery including work from a wide range of artists—some well-known like Bill Viola, George Legrady, Vibeke Sorensen, and Norman Yonemoto, and others--including some of our students—just getting into the game. Amidst this array, we also showed three works-in-progress from The Labyrinth Project—collaborations with gay chicano novelist John Rechy (aka The Sexual Outlaw) and independent filmmakers Nina Menkes and Pat O’Neill. Here’s how I described the exhibition in the opening paragraph of our catalogue:

“Sparks. Heat. Conflict. This is what friction generates. Using friction as a catalyst, our exhibit features work produced at the pressure point between theory and practice. It brings together artists from different realms, at different stages of their careers, working both individually, and in collaboration in an array of different media: installations and assemblage art, independent film and video; traditional and computer animation; photography and graphic design; literature and music; computer science and interface design; websites, CD-ROMs, and other hybrid forms of multimedia. Coming from different domains, the pieces challenge and contradict each other. What unites them is the focus on interactive narrative.”

We received fabulous feedback on the conference, claiming it had energized all those who attended and broadened their conception of what digital multimedia could be. Despite this success, I decided not to make this conference a recurring event. Instead, I wanted to start producing experimental works in collaboration with others—works that could realize some of the possibilities that were discussed at the conference. So I put together a creative team of three media artists—Rosemary Comella, Kristy Kang, and Scott Mahoy-- and that’s what we’ve been doing for the past seventeen years.

But, now that so much time has passed, that conference represents a valuable snapshot of what the discourse was like in the 90s. For, some of the essays in our anthology are even more revealing now than they were then—especially those that were foundational for the field (like Katherine Hayles’s “Print is Flat, Code Is Deep: The Importance of Media-Specific Analysis”) and those that presented historical precursors (like the pieces by narrative theorist Edward Branigan and early cinema scholar Yuri Tsivian). And it’s important that, not just the artists and editors, but most of the contributors to our volume went on to produce multimedia projects. We hope our “Interactive Frictions” helped make them do it.

Marsha Kinder began her career in the 1960s as a scholar of eighteenth century English Literature before moving to the study of transmedial relations among narrative forms. In 1980 she joined USC’s School of Cinematic Arts where she continued to be an academic nomad, with narrative as her through-line. Having published over one hundred essays and ten books (both monographs and anthologies), she is best known for her work on Spanish film, specifically Blood Cinema (1993); children’s media, especially Playing with Power in Movies, Television and Video Games (1991); and digital culture (including her new anthology Transmedia Frictions: The Digital, The Arts and the Humanities (2014), co-edited with Tara McPherson. She was founding editor of innovative journals, such as Dreamworks (1980-87), winner of a Pushcart Award, USC’s Spectator (1982-present) and since 1977 served on the editorial board of Film Quarterly. In 1995 she received the USC Associates Award for Creativity in Scholarship, and in 2001 was named a University Professor for her innovative transdisciplinary research.

In 1997 she founded The Labyrinth Project, a USC research initiative on database narrative, producing award-winning database documentaries and new models of digital scholarship. In collaboration with media artists Rosemary Comella, Kristy Kang and Scott Mahoy, and with filmmakers, scientists and cultural institutions, Labyrinth produced 12 multimedia projects (DVD-ROMs, websites, installations and on-line courseware) that were featured at museums, film and new media festivals, and conferences worldwide. Kinder’s latest work, Interacting with Autism, is a video-based website produced in collaboration with Oscar-winning documentary filmmaker Mark Jonathan Harris and Scott Mahoy. Since retiring from teaching in Summer 2013, Kinder is now writing a new book titled Narrative in the Era of Neuroscience: The Discreet Charms of Serial Autobiography.