Showcasing the Civic Media Project (2): Binders Full of Election Memes

/This is the second in a series of three entires, cross-posted from the Civic Media Project website. Check out the site for many more examples of the ways groups around the world are using digital media to help foster civic change. The site was created by Eric Gordon and Paul Mihailidis, the leaders of Emerson College's Engagement Lab, in anticipation of their forthcoming book for MIT Press, Civic Media: Technology, Design, Practice.

BINDERS FULL OF ELECTION MEMES:

PARTICIPATORY CULTURE INVADES THE 2012 U.S. ELECTION

Erhardt Graeff

Participatory culture handed the 2012 U.S. presidential election season a bumper crop of political memes. These “election memes,” largely in the form of image macros, took sound bites from the candidates’ debates and speeches and turned them into “digital content units” of political satire “circulated, imitated, and/or transformed via the Internet by many users,” to paraphrase Limor Schifman’s definition of “internet meme” (2013, 177).

Image macros like the lolcat, feature bold text on top of an image, often a “stock character,” and like all Internet memes are “multi-participant creative expressions through which cultural and political identities are communicated and negotiated” (Ibid.). This case study focuses on three popular image macro-based election memes that came out of the 2012 US presidential election cycle: "Fired Big Bird," "Binders Full of Women," and "You Didn't Build That," and argues that sharing such memes is a valid form of political participation in the style of what Tommie Shelby calls “impure dissent” (forthcoming).

Case 1: Fired Big Bird

During the televised debate on October 3, 2012, Mitt Romney discussed ways he would reduce the deficit. One of which was the government subsidy to the non-profit public broadcaster PBS. He mentions the beloved character of Big Bird in course.

"I'm sorry Jim, I'm gonna stop the subsidy to PBS. [...] I like PBS, I love Big Bird, I actually like you too, but I am not gonna keep spending money on things to borrow money from China to pay for."

What emerges immediately is the proliferation of image macro memes, new Twitter parody accounts, and a significant amount of media attention.

This case sees political discourse play out as both Anti-Romney and Anti-Obama, with competing narratives when the meme hits some threshold of attention. And mainstream media plays a key role in amplifying the memes.

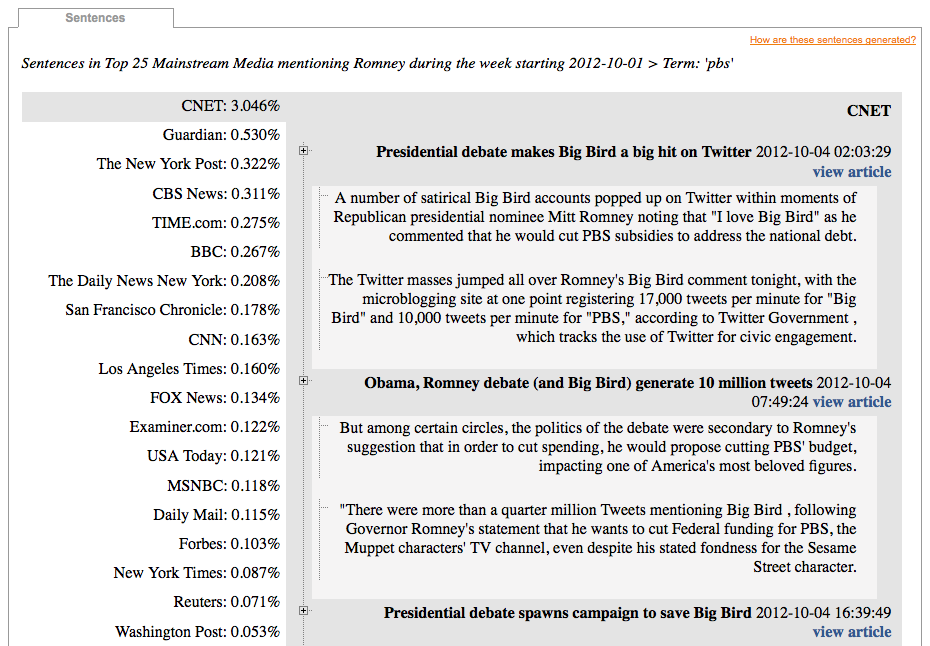

Using the media analysis tool Media Cloud, I found “pbs” among the most mentioned words in relation to "Romney" in stories from the top 25 most trafficked online mainstream media sources during the week of October 1, 2012.

Then, I used Media Cloud to browse the specific sentences mentioning PBS in those “Romney” articles.

A CNET article from the night of the debate discussed the social media discourse around the debate and Big Bird in particular. They even drop in one of the image macros shared on Twitter, with the caption "Credit: SadBirdBird/Twitter," actually giving credit to one of the parody Twitter accounts. The NYT's Lede blog, which covers the media, also included the memes and talked about how the Big Bird debate confused international election watchers.

The headlines and content of these articles addressed the meme directly, and journalists used the discussion of the shared image macros and parody Twitter accounts as part of their coverage of debate performance and public opinion. And while it is impossible to say that there wouldn't have been a significant media event around PBS and Big Bird without the intervention of hundreds of memes and thousands of tweets, these indicators help make the case for memes as legitimate political discourse.

Furthermore, the Democratic Party and Obama Campaign immediately capitalized on the attention paid by the Internet and mainstream media to the Fired Big Bird election meme. The day after the debate the Campaign’s Tumblr account passed on two screenshots, one of a Fired Big Bird meme from The Democratic Party’s Twitter account and another meme from the Harris County Democratic Party’s Facebook page. Obama was also at a rally in Denver the day after the debate where he joked, "We didn't know Big Bird was driving the federal deficit!" And six days after the debate, the Obama Campaign released a polished campaign ad about Big Bird.

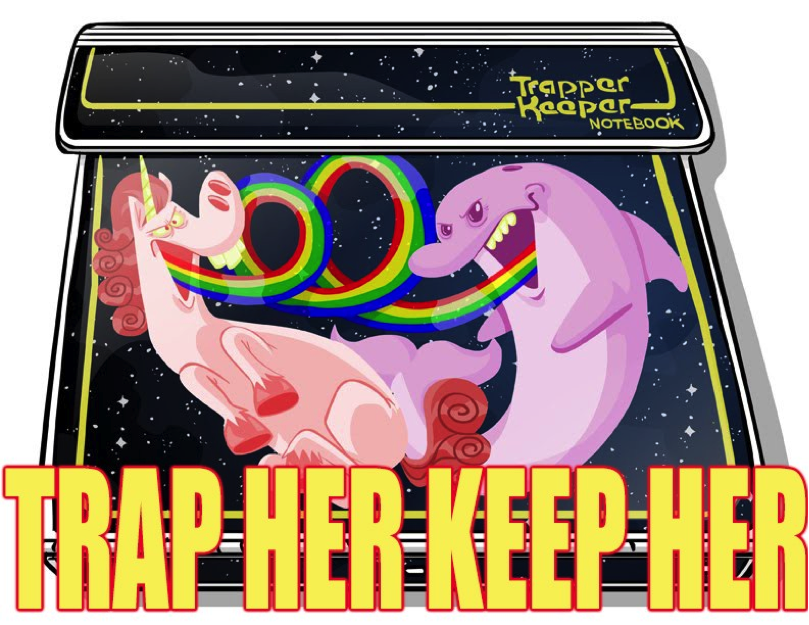

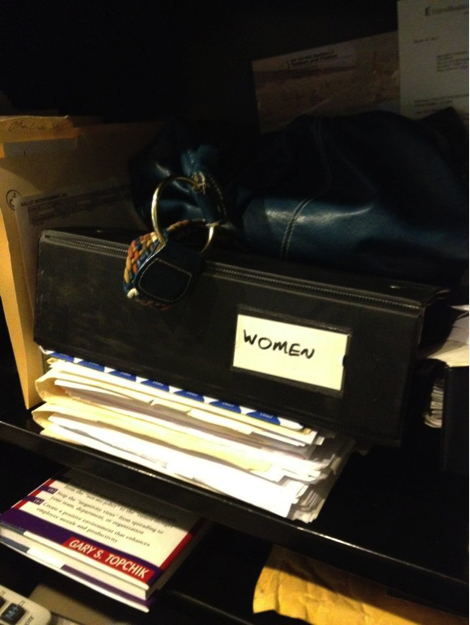

Case 2: Binders Full of Women

During the second presidential debate on October 16, Mitt Romney responds to a question about pay equity, mentioning that when he was Governor of Massachusetts he was given "binders full of women" as candidates for positions.

"And I said, 'Well, gosh, can't we—can't we find some—some women that are also qualified?' I went to a number of women's groups and said, 'Can you help us find folks?' and they brought us whole binders full of women."

23-year-old experienced social media manager Veronica de Souza was watching. And while parody accounts were springing up on Twitter, she went to Tumblr, registered bindersfullofwomen.tumblr.com, and started making memes and inviting others to contribute.

This case was strongly centered around the specific Tumblr blog created by de Souza the night of the debate. She made it open to contributions and curated them. Tumblr is designed for sharing content through its “submit” and “re-blog” features that in one click allow content to be shared on a Tumblr blog.

Mashable then interviewed de Souza after the fact. She talked about creating the Tumblr blog and a few starter memes: "It's so easy to create a new Tumblr that is attached to your own. Creating a new Twitter account means you have to create a new email address...it's more complicated. Also, with how fast Twitter was moving, it would be hard to break through" (Haberman 2012). She admits that she wanted to share and be noticed for her project.

De Souza also reflected on the political aspect of her meme curation: "People keep asking me politically charged questions. Will it swing voters? Maybe the original statement, but not the meme" (Ibid.). She continues, "I didn't mean it as a political statement—I just thought it was funny and I knew it would be a thing" (Ibid.).

Even if de Souza didn’t believe the election meme would swing voters, the attention it drew to related issues was a potent opportunity for the Obama Campaign. Starting the night of the debate and lasting for the next three days they posted images andquotes to Tumblr highlighting the Obama’s stances on women’s equality and right to choose.

Case 3: You Didn't Build That

President Obama gave a speech on July 13, 2012 at a fire station in Roanoke, Virginia. He was trying to make a point about the role of government and taking aim at the business credentials of the self-made Romney.

"If you were successful, somebody along the line gave you some help. [...] Somebody invested in roads and bridges. If you've got a business—you didn't build that. Somebody else made that happen. The Internet didn't get invented on its own...."

Republican and conservative Internet users started generating memes, eventually pulling in the Republican Party, Romney’s Campaign, and mainstream media.

And then the GOP itself created a set of slick branded image macros.

After a few days of individual Internet users and independent conservative activist organizations creating memes, on July 17, the Republican National Committee’s opposition research team caught on and generated five GOP.com branded memes, sharing them on their Tumblr blog. That same day, Romney’s Campaign Facebook page offered a shareable image retorting “The Government Doesn’t Build Businesses… Hard Working Americans Do.” The next day, the lead story in the RNC’s research memo was “You Didn’t Build That.” The media coverage of this election meme was strong enough that the Romney Campaign held on to the message over the next two months with slogans like, “I built my business, Mr. President,” “Built by Us,” “We Did Build It!” and then theming the GOP Convention on August 28, “We Built It.”

The Power of Sharing

From the start, the popularity of these image macro memes derives in part from the relative ease of generating and sharing them. Image macro meme generator websites, like quickmeme.com, memegenerator.net, and imgflip.com, make it even easier by managing the process of uploading your own image and overlaying the classic bold white font with your own words added through a text box. They also host galleries of all of the memes created using the same image, which may facilitate their sharing. I argue the real power of this form of political participation is the ease of sharing.

Sharing or circulating a simple image macro via personal social networks, what Jenkins, Ford, and Green call “spreadable media” (2013), represents a political speech act itself. In the networked public sphere (Benkler 2006), barriers to entry have been lowered but so to have the barriers to sharing, with ready audiences on Twitter coalescing into publics around hashtags, on Tumblr through tagging and curation, and on Facebook through shared identity construction.

Shifman, Coleman, and Ward (2007) identified the growing importance of user-generated political humor during the 2005 UK general election as a form of online political participation, but the overwhelmingly cynical quality of the humor left the authors unclear on its utility to promote further participation. But looking at new social movement models like the Arab Spring, Occupy, and the Spanish indignados, Bennett and Segerberg (2012) identified the power of meme sharing, calling it the “linchpin of connective action.” They argue that sharing political memes can power “connective action networks” through personal expression shared over social networks rather than top-down forms of collective action. In some cases these networks can be organizationally-enabled through technological support and moderation to produce loosely coordinated, yet effective movements.

In the case of the 2012 U.S. presidential election memes, the organizations involved in the connective action are the campaigns. In past elections, they developed the capacity to curate attention toward and shape the framing around popular user-generated political content—most notably 2008’s “Yes We Can” video (Wallsten 2010). They now leverage networks of digital activists coordinating with celebrities who have large followings like those involved in the “Yes We Can” video, and backchanneling with savvy political operatives with prior campaign experience like Matt Ortega, the progenitor of several other 2012 election memes (Seitz-Wald 2012).

Although this corroborates the value of connective action and the argument that election memes represent legitimate political speech acts, it also calls into question the quality of personalized expression and grassroots mobilization involved. But “authentic” and even cynical political participation through memes can coexist with their adoption and exploitation by professional political organizations.

Election Memes as Impure Dissent

In a forthcoming paper, Tommie Shelby discusses hip hop as political speech act, and stresses that this form of dissent should not be understood on the model of civil disobedience: it is not meant to garner the notice of the state or other citizens to make a moral point, nor is it meant to demonstrate any moral purity or be respectable. Hip hop flaunts morally or politically objectionable content, which can lead to its dismissal by others: not unlike election memes which debase things or place them out of context to create humor.

Shelby cites Albert Hirschman's classic text Exit, Voice, and Loyalty, in which dissent comes in two forms: exit and voice, which can be used in tandem as effective political action (1970). But in cases like resignation to the current political system, or an unwillingness to emigrate, voice is the only option. And voice is meant in most cases to influence power, to alter the status quo. But Shelby argues that we should expand voice to mean symbolic expression, which can still be highly political but not concerned with ultimate impact on those in power. This is how the creation and sharing of cynical election memes make for valid political participation.

The propagation of these politicized cultural artifacts may seem trivial and guilty of the slur of "slacktivism" online, but the sharing does real political work in terms of creating a moment and a networked public with power greater than the sum of its parts. Friends or followers are exposed to the sharer’s otherwise unspoken political opinions and given the opportunity to participate by forwarding the same meme they did.

Meme sharing indicates there is something worth paying attention to in that moment. Maybe it is just funny. Maybe it is a little too true, which underlies the humor and implores us to pass it on. A lot of memes act as shibboleths—they indicate that you are part of the in-crowd, you get the joke, you were there when it happened. This is the power of the meme speech act. It quickly creates a networked public from its in-group. That feeling of inclusion can inspire further and future discourse.

Shelby argues that the value of dissent may not be social or political but in how well it reaches its intended audience without having to incite them to activism. And dissent is a public act that creates a public among those it reaches. The messages of dissent call out to be agreed with, rebutted and sometimes acted upon, says Shelby, which is how memes are a form of impure dissent like hip hop, empowered by the act of sharing.

There is the fear that commercialization in hip hop or professionalization in internet memes undermines this power. Shelby argues that impure dissent is a personal act of expression and will always be judged by the audience, critiquing the attitude and justification of the source. Commercial rappers simply have less political credibility. While Stromer-Galley argues that cooption of participatory culture practices by contemporary campaigns have nothing to do with democratic practice and are just about winning (2014), there are real moments of political discourse that emerge through meme sharing—these are moments of personal identity construction and negotiation to return to Shifman’s definition of internet memes. There is room and a need for sharing election memes as impure dissent and as cynical political participation, which might be amplified by campaigns but cannot be replaced by them.

References

Benkler, Yochai. 2006. The Wealth of Networks: How Social Production Transforms Markets and Freedom. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Bennett, W. Lance, and Alexandra Segerberg. 2012. “The Logic of Connective Action.” Information, Communication & Society 15 (5): 739–68.

Haberman, Stephanie. 2012. “Talking Internet Gold With Creator of 'Binders Full of Women' Tumblr.” Mashable, October 17. Accessed June 7, 2014. http://mashable.com/2012/10/17/binders-full-of-women-tumblr/.

Hirschman, Albert. 1970. Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Jenkins, Henry, Sam Ford, and Joshua Green. 2013. Spreadable Media: Creating Value and Meaning in a Networked Culture. New York: NYU Press.

Seitz-Wald, Alex. 2012. “Matt Ortega: The Man behind Mitt Romney Memes.” Salon, March 23. Accessed June 7, 2014. http://www.salon.com/2012/03/23/matt_ortega_the_man_behind_mitt_romney_memes/.

Shelby, Tommie. forthcoming. “Impure Dissent: Hip Hop and the Political Ethics of Marginalized Black Urban Youth.” In From Voice to Influence: Understanding Citizenship in a Digital Age, edited by Danielle Allen and Jennifer Light.

Shifman, Limor. 2013. Memes in Digital Culture. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Shifman, Limor, Stephen Coleman, and Stephen Ward. 2007. “Only Joking? Online Humour in the 2005 UK General Election.” Information, Communication & Society 10 (4): 465–87.

Stromer-Galley, Jennifer. 2014. Presidential Campaigning in the Internet Age. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Zuckerman, Ethan. 2013. ‘Beyond “The Crisis in Civics.”’ Paper presented at the Digital Media and Learning Conference, Chicago, Illinois, March 14–16. Accessed June 7, 2014. http://www.ethanzuckerman.com/blog/2013/03/26/beyond-the-crisis-in-civics-notes-from-my-2013-dml-talk/.

Erhardt Graeff is a PhD researcher at the MIT Center for Civic Media and MIT Media Lab. His latest projects involve building civic technologies that empower people to be greater agents of change, performing quantified analysis of media ecosystems, and documenting new forms of civic participation enabled by digital media. Beyond academia, Erhardt is a founding trustee of The Awesome Foundation, which gives small grants to awesome projects. Erhardt holds master’s degrees from Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the University of Cambridge and two bachelor’s degrees from Rochester Institute of Technology.