WARNING! Graphic Content: An Interview with Political Cartoonist Mr. Fish (Part Three)

/I was struck by your phrase, “the democratizing power of scatology.” In what sense is scatology democratizing? Are there times when scatology gets used in more authoritarian or fascistic ways? By referencing the “democratizing power of scatology” I’m partly echoing the preeminent manifesto that has done more to unify the planet with its nonpartisan secular worldview than any other book perused by human eyes – of course I’m talking about Taro Gomi’s seminal work, Everybody Poops – and I’m partly acknowledging how an interest in obscene matters, which is universal, reflects our sameness in defiance of those whose airs and megalomania insist that the opposite is true.

I’m not 100% sure what you mean about scatology being used in an authoritarian or fascistic way, unless you’re referring to circumstances when those in power assume that the use of scatology by the proletariat and lower classes is proof that they are unsophisticated vulgarians worthy of ridicule and/or marginalization and/or abuse. If it is, then, yes, you’re right, but I’d argue that that is less a description of the effect of scatology and more an example of how thuggish and delusional imperiousness often is.

You cite Boss Tweed’s discussion of cartoons as gaining their power because they spoke to people who could not read the printed articles in the paper. This idea of comics as a medium for illiterates runs across its history and there remains a sense that comics speak to people who would not understand or be interested in more “legitimate” or “legitimized” forms of expression. And this moves beyond comics to other forms of satire -- for example, the contempt I hear among some intellectuals about young people who get much of their news from memes or from the Daily Show. How do you respond to this claim that cartoons may be “dummying down” political discourse?

There are certainly examples of cartoonists who dumb down political discourse, just as there are examples of writers who commit the same violation, just as there are examples of other kinds of artists and public intellectuals who dumb down the entirety of our cultural acumen with the ideas that they advocate. Rather than look to the whole profession of any of those examples, it would be more instructive to look to the individual artist or thinker and the circumstances that produced the commentary being offered to access whether participation in a dialogue is additive or subtractive.

That said, it should not be overlooked that a great deal – some might argue all – of political discourse is the very deliberate “dumbing down” of humanitarian discourse. (Recognizing the need to reverse our negative impact on the environment, for example, is made perverse by the political notion that nothing can be done to save the ecosystem until a solution can be devised that doesn’t impact the business sector.)

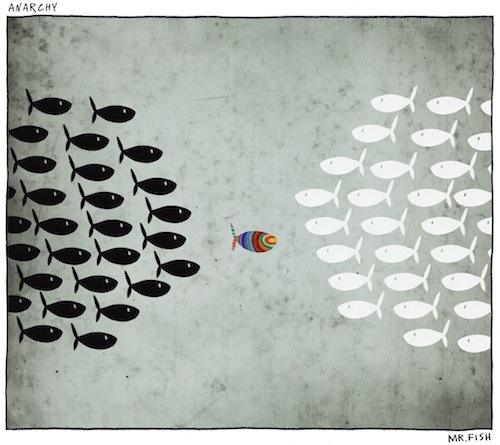

And while I might agree that the majority of cartoonists could legitimately be accused of simplifying political conversation, I’d argue that they are not doing it for the purpose of dumbing down discourse, but rather for the purpose of introducing clarity, common sense and sympathy into the national political dialogue.

A cartoonist, when he or she succeeds, makes politics accessible and understandable and, quite frankly, usable to a large portion of the public who, because of race, education level, income inequality, or any number of schlock justifications for marginalization from elite society, would have no easy way to decode and decipher how and why the world functions and dysfunctions as it does.

As we think about the political effects of cartoons, you show us many examples where cartoonists have ridiculed those in power, but also many where those without power, those on the margins, have been depicted in stereotypical and demeaning ways. Do these two functions get achieved through the same kinds of artistic mechanisms? Is there a way to meaningfully distinguish between these two different kinds of political use of comics as a medium?

Indeed, the use of stereotyping in cartooning will always seek to ignore the humanity of both those in power and those dismissed or abused by power for the sake of either making a joke or exaggerating a virtue or a prejudice in service of expressing an opinion of criticism or contempt.

Is the artistic mechanism of ridicule the same for slandering a king as it is for slandering a peasant? Sure it is, particularly when we recognize art as a language, and one that is made up of an alphabet that is just as indifferent to the ideas that it conveys as a pen would be to the words it is writing.

Thus, there can be no consistent or meaningful way to distinguish between good or bad stereotypes any more than there is a consistent or meaningful way to distinguish between good or bad willful misrepresentations of an intrinsic fact that is open to an infinite number of interpretations. Put simply, it is the intention of the cartoonist that must be judged, not the megaphone – the medium! – through which he or she broadcasts his or her message.

I generally share your celebration of the uncensored imagination, but this raises some questions at the same time. Are there images that are so problematic, so hurtful, that they should not be reproduced and circulated? Does a refusal of censorship necessarily imply a lack of criticism? What should be the society’s response be to images that can be very difficult to embrace?

One of my favorite quotes from Lenny Bruce is, “Knowledge of syphilis is not instruction to get it.” So, no, I don’t believe there are images that are so problematic and so hurtful that they should be censored, for the same reasons why I don’t believe in the censoring of the written word.

In fact, I have never found the parameters drawn by the dominant culture to indicate acceptable behavior or appropriate rules of artistic conduct reliable measures of anything but our most finicky and unimaginative natures.

Still, if the images that we’re talking about are truly toxic and corrupting of our better judgment, better to have them scrutinized in the light than allow them to metastasize in the dark. Knowledge of atrocious and pernicious ideas, whether expressed through text or image, tests the integrity of one’s moral center by providing something contrary with which to compare, resist and rail against.

Exposure to idiocy also serves to unmask the deranged logic of those who advertise the questionable ideas as sound so that the mathematics of the argument can be tested in an open forum and fact can be meted out from conjecture.

Additionally, when straight society misinterprets an unfamiliar wisdom and labels it as deranged logic, it is important to have mandates for free expression in place so that the positive effects of innovative thinking can flourish and not be suppressed by priggish bureaucrats blind to pioneering intellectual advancement.

Can you speak a bit about your own priorities as a political cartoonist? How do you decide which images are worth drawing? What causes require your skills?

Dwayne Booth has been a freelance writer and cartoonist for twenty-five years, publishing under both his real name and the pen name of Mr. Fish with many of the nation's most reputable and prestigious magazines, journals and newspapers. His work has appeared in Harper’s Magazine, the Los Angeles Times, the Village Voice, the LA Weekly, the Atlantic, The Nation, Vanity Fair, Mother Jones, the Advocate, Z Magazine, Slate.com, MSNBC.com and on Truthdig.com. In May 2008 he was presented with a first place award by the Los Angeles Press Club for editorial cartooning. In 2010 and 2011 he was awarded the Sigma Delta Chi Award for Editorial Cartooning from the Society of Professional Journalists. In 2012 he was awarded the Grambs Aronson Award for Cartooning with a Conscience. His most recent books are Go Fish: How to Win Contempt and Influence People, Akashic Books 2011, and WARNING! Graphic Content, Annenberg Press 2014. He is currently teaching at the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania.