Comics as Poetry: An Interview with David Mack (Part Five)

/Exchanging Letters HJ: I am very interested in the relationship which emerges between Akemi and Kabuki in Skin Deep and beyond. I find myself wanting to compare the core situation with the depiction of Evie's captivity in Alan Moore's V For Vendetta but also Nick Bantock's Griffin and Sabine books, which are told through a series of letters and postcards between the protagonists, one of whom may well be a figment of the other's imagination. I wondered if either of these offered an inspiration for this relationship and, if so, in what ways you rethought those situations for this story?

DM: Griffin and Sabine, I didn't see until later, when a friend of mine who was involved in the story told me about it. I appreciated what was happening there and how it related to what I had done in Kabuki. V For Vendetta and Watchmen were the other books that I read when I was 16. I could never escape what I learned from them in those really formative years.

There's also another story I read when I was very young called The Hiding Place. It was about people hiding out in Nazi Germany. A woman was imprisoned, and she only got two sheets of toilet paper per day. That was her ration. But people would use that toilet paper as barter systems. Some people would use them just to write on and to give other people. That directly corresponds with Akemi in Kabuki where Akemi is writing on sheets of toilet paper, folding it into origami, and dropping it through the vent, and Kabuki is responding the best she could.

I had a good friend Andy Lee at Washington University in St. Louis. I was very ordered about certain things, but he used a sort of Zen chaos that I started to incorporate. At two o' clock in the morning, he said, "I have class tomorrow. I have to turn in a story, so I've got to work on that." I said, "Oh, that's great! What's your story about?" And he said, "I have no idea. I haven't thought about it or started it at all." I said, "What?" He said, "I have to turn it in at 9 a.m." I said, "You haven't thought about it? You haven't written notes about it?" He said, "No, I have no idea. What do you think I should write, because I'm going to be writing all night until 9 a.m." I said, "Oh my goodness! This is ridiculous! That's not how I do things in my orderly fashion." He said, "Well, can you help me write it? If you write it, too, we can write twice as fast." And so I said, "The only way that two people can write a story twice as fast is if it's a story about you writing a letter to me and then me writing a letter to you. Here's what we'll do. We'll make two characters, and, that way, neither of us is dependent. We don't have to work anything out first. Here's the basic idea: I write a letter for your character, and then your character writes a letter back to me, and we'll go back and forth."

We wrote it all night along, and that became his fiction story. I wrote half of it from the character I created, and he wrote half from his, and it was so much fun. It was so spontaneous, and neither of us were tired because it was so ridiculous and fun. It made such perfect sense in the middle of the night that I thought I should do a comic book that way. That's how that issue came about, and it was a completely different way than I ever wrote a story before: an entire comic book just being these two people writing letters to each other.

HJ: Going back to origins of the novel, the epistolary form has a long history. Many of the early novels were exchanges of letters and diaries and so forth, out of which we come to know the characters and their relationships.

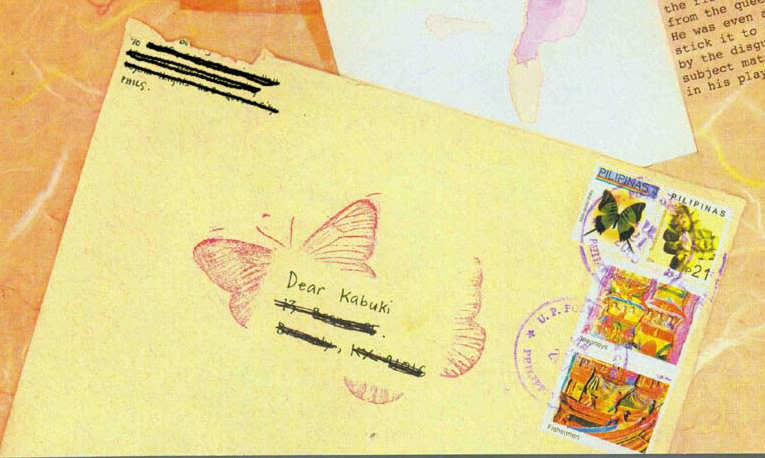

DM: I was probably ignorant of that at the time, but, since then, I really appreciate that idea. I named a chapter in Alchemy "Epistolary" because that issue was very much central to the story. The chapter became actual letters in envelopes. When I knew I was going to do this issue where Akemi is traveling the world and she's writing back to Kabuki, I told readers on message boards, "Send me your letters. Send me your stamps. I need stamps from all over the world." All these readers sent me hundreds of envelopes with stamps from a variety of countries, and some of them were so beautiful and such cleverly made envelopes, and the handwriting was on them in an interesting way, and the stamps, I think there were 10 different stamps on the same envelope from the Philippines. They were so beautiful. I used those actual envelopes and stamps that readers sent as a central piece of each page in the book and just covered their actual return address and put maybe Akemi or Kabuki. This kind of thing and made the fans an active creator of the pages of the story.

HJ: In the documentary The Alchemy of Art: David Mack, you talked about the Scrabble tiles you used in the Echo book in much the same way. They were submitted by readers, so it sounds like you have a kind of ongoing relationship with readers.

DM: I do, in a couple of different ways. Once they see you start using 3D objects, fabric and collage in your work, some of them just seem compelled to start sending you stuff" "I saw this. I thought it was interesting. Maybe you can use it for a page." I say thanks and, if I do, I'll put their name in the back of the book. There's been moments where it arrives just in time. There's a woman called Miss Fumiko in New York who sends me things a lot. I remember one time I was doing a Daredevil cover, and I wasn't quite happy with how it was going. Then, the mailman banged on the door. It was all these metal pieces from Miss Fumiko. I set them directly on the painting I was working on at that moment and said, "Oh, these are a great border for this page." In general, I get a lot of stuff in the mail that I put in a box and pull out when I'm doing a collage.

Also, these comics come out in serialized form first, and then it's different if you read The Alchemy as an entire collection versus if you read once and then wait two months for the next one to happen because that two months gives people time to speculate. If you read the whole collection, the entire story is right there, but the serialized form provides an interesting gestation period for readers to have. They read the first issue, and they say, "Oh, what does this mean? Who's that knocking on the door at the end of this issue? I think it's going to be this person, or could it be this person, or is this Akemi's intention, or is it really something else's?" They start speculating a lot. Sometimes, they'll speculate about things I hadn't thought about before, and I'll think that's an interesting idea to actually do or throw in as a red herring. I'll start getting ideas from reader speculation not as part of the main story points, but as a little something to deepen it a bit, to add more texture to the story.

Final Reflections

HJ: When I introduce your books to people, I often say they are to regular comics as poetry is to prose. I'm just wondering if you do see your work as sort of operating in a different register than some of the mainstream superhero comics?

DM: I think it's safe to say most of this stuff is different than the mainstream super hero stuff. I like that comparison. I don't remember who said it. Maybe it was Rimbaud who said that "poetry is the language of crisis," which I find a really interesting idea. I like the idea that poetry has spaces in it for the words to mean exactly what they're saying, but, at the same time, the words can mean something extra that you don't immediately see. It depends on what the reader sees, the life experience they have or what baggage they're bringing to it. I do try to encrypt that in the story. I do have a hierarchy of story structure where I want to get across what's actually happening in the story first and the clarity of that. But, second, there are other things in the story that probably won't be revealed on the first read but hopefully will be very rewarding on repeat readings.

You can get to those other levels in film and music, too, but I think it might be more nuanced in poetry because the images are so crystallized and concentrated. Each word is usually sparser but seems so much more packed with meaning next to another word also packed with meaning, next to another word packed with meaning that can unravel itself like DNA when you read it years later.

A lot of the things I like--whether it's music, film, or artwork--give me that sense that there's something I can totally relate to the first time I read it, no matter how old I am. When I'm a child, I read it and I love it. I hear the song. I love it. Ten years later, I experience that part again, and I like it for totally different reasons that I never saw before. I really like that kind of feeling, and I hear from readers that they sometimes get that feeling about reading my work, too.

One comparison I get is that readers say, "It takes me 10 minutes or 20 minutes to read a regular comic book. I read it, and I learn what happened in this chapter of their life, and then I move on to the next part. But, when I'm reading your comics, it takes me a really long time to read it because I like to savor every moment of it and read each word over and over and look at what's happening in the background." Then, they'll also say that, a year later, they read it again and get a completely different experience out of the second or third reading. I like that idea that, at a different part in your life, you can appreciate it for a different reason.

I've also had people come and tell me, "When I first read Kabuki, I hated it. When I first saw your artwork, I wasn't sure what to think of it. It made me feel weird." And then they'll come back and say, "I read it again, and now I love it. Now, it's my favorite thing." It reminds me of that experience I had as a kid with my first Frank Miller book. I was almost traumatized. Then, I read it three years later, and I thought, "This is fantastic." Now I get that kind of response.

THE END