Comics as Poetry: An Interview With David Mack (Part Three)

/"Contrast Is Everything" HJ: While we're on color, you clearly have thought deeply about color theory. What assumptions shape your choice of color schemes for your comics, and how do you think your approach differs from the way color gets used in mainstream superhero comics?

DM: I have a BFA in graphic design, which entailed taking all of the design classes and all of the fine arts classes, too. So I do have a lot of experience in the color wheel and what colors are complementary and color theory. That said, there's probably a lot of intuition involved in it as well. For me, contrast is everything. Contrast with color. Contrast with panel layout. Essentially, when you're composing panel layouts and using color in story, I think it's probably akin to composing music, where there's certain buildups to it and there's certain lows and certain highs and there's a certain crescendo to things. I think designing comic pages uses a similar kind of contrast. It's all about creating a hierarchy on the page and a hierarchy in the story and directing the reader's eye so that they finish a certain amount of things.

On a page, you want their eye to look at some panels longer than other panels and then to rest at certain place and have an access point at a certain place. So there is a hierarchy about the page that color plays an important part of. A bright color is going to grab the attention. You can have the majority of the page in muted tones, and then you can have a larger panel at the bottom. The size of that panel and the contrasting color is really going to be sort of your crescendo moment for that page. I think there's a relationship between how long it takes you to make the drawing in the panel and how long someone reads it.

I think the less detail that is in this panel, the quicker it is going to be read. It still says everything it needs to say, but, if you want someone to read that panel quickly to get to the next one, don't overdo it. If you want them to look at it longer, you put more time into that one. I love that contrast.

There's another kind of contrast. You might render something a little bit more realistic in one image or use some photo reference in a close up so it feels like a real human, but you don't want to do that in every panel because it'll just cancel itself out. So, for contrast, you want the other things that are read more quickly to be more abstracted. Those go a little quicker, and then you sort of build up to something else, and color's a part of that. When someone opens a book, you really see two pages at the same time. Sometimes, when you're drawing, a lot of people just think they're doing one page, but it's really like a big meta page; you're seeing those two pages at once. I'm very conscious of that when I work on pages. I work on the design as if someone's looking at them, and I know the colors on this page have to work with and complement the colors on the opposite page. You want those to contrast, then, with the page they're turning next, so that'll be a surprise.

HJ: You touched on something I was going to ask you about. One of the striking features of your work is the constant shifts in modes of representation. Fairly realistic images exist alongside very abstracted images, sometimes of the same character on the same page. What do you see as the value of such varied techniques in shaping the reader's experience of your work?

DM: I might do it to a greater degree from scene-to-scene. The Alchemy, for instance, probably has the most diverse approaches across the whole story, but each chapter has a visual metaphor. Each issue is a little different from the next issue. Within each issue, each scene changes quite a bit, and, you're right, often on the same page. I use a certain amount of contrast.

When you boil it down, the lowest common denominator of a comic is what the reader fills in between the two images. If you have a panel that has a cat on the table, it's just a cat on the table. Then, you have another picture that is a cat on the ground. On their own, that's what they are. Next to each other, the reader says that cat jumped off the table, and now it's on the ground. I think the same thing happens in terms of changing color or changing the way something is rendered. The reader processes that. You can do it incredibly overtly.

If you want to show a certain amount of emotional or psychological change in the character, you can do it pretty subtlety in certain degrees, and I think it's another tool that the writer has to tell a story through implication, through just how the reader's mind works. If it's a shocking situation, I would draw the panel before the catalyst of shock happened in a different way than the one that where the shock happens. I might do the first one in pen and ink and make it more streamlined and calmer. Then, I might do the other one with a wash of watercolor or acrylic down over it. Then, maybe I'll draw it jaggier in pencil or something like that when the moment of realization happens to the character. I don't have to use any words and take any extra space in the page to tell what's happening. I don't even have to draw that differently. I can do it just by using a different medium or drawing it a little bit stranger. I think the reader processes it emotionally for the character. I think it's just one of the assets that comic books as a medium have at their disposal.

Make Mine Marvel

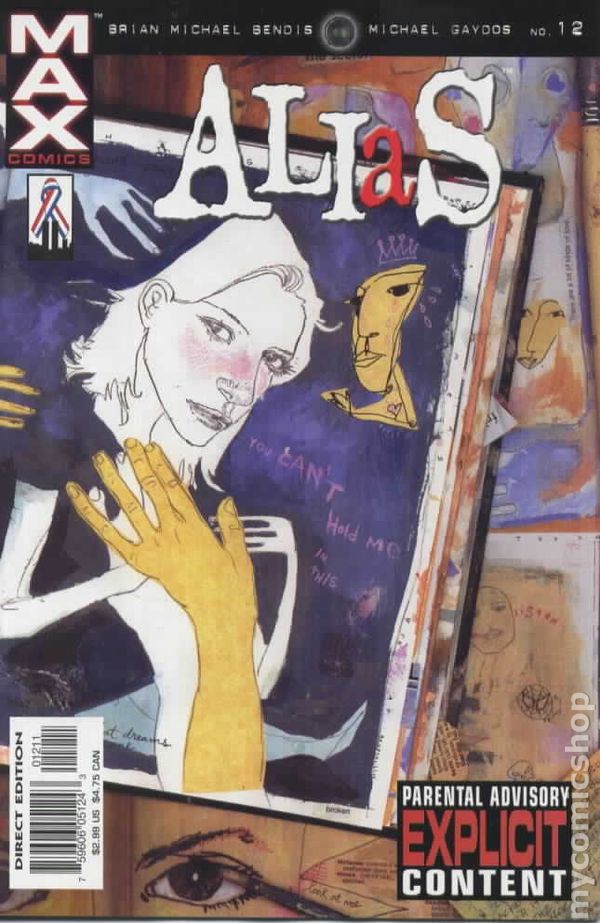

HJ: One of the first places I became aware of your work were the covers for Alias, which is designed to signal a different kind of relationship to this comic. This is not your typical Marvel comic, and you get it just from seeing it on the stand next to the other Marvel titles. I wonder what thought went into the design of those covers.

DM: You're absolutely right! That is an exact conversion that Brian Bendis and I had. I attribute that directly to him. Whether in person or on the phone, he told me almost exactly what you just said. He said, for the covers for Alias, it shouldn't look like a comic book at all. Make these look like a book that you see when you walk into a bookstore. As soon as you see it, you know that Alias isn't like any other book that Marvel has. And, often when I'm designing covers for comics, I very much am considering it's the cover of the book and it's what's selling the book. It's not just the book itself. You have to consider this in context of it being on the wall in a comic book shop next to 100 or more books, so you don't necessarily want to use the same kind of mediums or designs that are being used in those other books. The nature of the cover is to make it jump out from all the things it's next to, so I always think in those terms.

Brian was very specific about this one. He said, "Maybe for a different storyline, we could use a different set of media or different vibe." Often, Brian suggested to me in detail what he wanted. Other times, he would just give me the script ahead of time, and he would just say, "Read the script and do whatever you want for it." So, it was pretty half-and-half. There were issues where he'd be very specific. Rick Jones is like a folk singer, so for the cover of one issue, he said, "Make really crappy music flyers. Make them yourself. Make them at Kinko's, and go post them on a pole somewhere on top of other ones. Take photos of that, and make that the cover." So that's what I did. I made flyers for the character in the story and then made a bunch of extra fake flyers, too, and I put them on a pole on top of all other real flyers in the middle of the rain and then staple-gunned it to the pole. They were wrinkled and rained on, and I took photos of it.

So there were times he wanted things for precisely for what the story was. Another time, there was a story where a girl was missing. They find her diary, so he said, for this, all the covers are pages from this girl's diary. So I took a sketchbook, and I filled a complete sketchbook as if I were a teenage girl. These were his instructions: "Pretend you're a teenage girl, and you're really mad. Make a whole diary of this girl with all these drawings and clippings.' So I did that without knowing which pages would be the cover. After I made that, I took photos of some of the pages and used them as covers for that issue series.

HJ: I am especially interested in the changes in style which occur when Joe Quesada is working from your script for Parts of a Hole. He seems to pull some of your techniques more into the mainstream of superhero illustration. What similarities and differences do you see in the techniques involved?

DM: That was such a great experience. I worked with Brian Bendis on Alias. For my first Daredevil story, I worked with Quesada - that was my first work ever for Marvel. I should say also that's one of the wonderful things about comics in general and working at Marvel--the spirit of collaboration. I have the Kabuki books where I have 100% of everything entirely on my own, and there're no editorial suggestions or anything. It's great to have that. But it's also really nice to have a project where you work with other people who are really bringing their A-game and bringing a whole other set of tools to the table that I wouldn't have.

So, working with Joe was really wonderful. When I'm writing for another artist, I write differently than I would write for myself because I'm going to write what I think are maybe that person's strong points from my perception, or those things that they would do better than I would do. I would write to convey that, and I would also have a conversation with Joe and say, 'What would you like to draw from the story? What do you think you would really shine on? What do you think are aspects that you're hoping to get out of this?" It's just a great conversation to have. Working with Brian Bendis, I had that situation too.

Every time I would write for another artist, I would send them layouts. Not that I wanted to necessarily have them do what my layouts were, but some of the script was a little unconventional in terms of its description of pages. So I sent Joe layouts that just said, "The script is what it is, but this is to give you a sense of what I mean by that description. When I said the first panel was a puzzle piece over here and the second panel is a puzzle piece down here, this is what I'm thinking about." Joe would take my layouts and use the best parts of or the parts he connected to. He would marry that to his own unique graphic sensibilities and create a hybrid art style, using some of the graphic things I was putting into the layouts and his own natural vibrancy, how he drew.

HJ: As you know, I am very interested in the aesthetic tensions which surrounded your work on Daredevil - especially the Vision Quest book. Can you provide some context as to how you were able to experiment so broadly within the parameters of the superhero comic?

DM: It's interesting. That book originally was going to be an Echo limited series. I don't know if you were aware of this. When I did that first Daredevil story, I asked Joe Quesada [by now, editor-in-chief for Marvel Comics], "What do you want out of this?" He said, "I want you to create a brand new character for Daredevil in the process." It was right after Kevin Smith finished his Daredevil run, so I wanted to continue with what Kevin was doing and acknowledge that and incorporate it into the story. But Joe also wanted a brand new character. He said that a lot of Daredevil's antagonists or villains are secondary Spider-Man characters that crossed over to this book, and he would like to see a new person unique to the Daredevil story. So that's where Echo came from, in a way starting as a villain in the story but also a potential love interest.

After that story, he told me he was getting requests from other writers to use Echo in the Marvel Universe, but he said before he was going to give the okay to that, he hoped that I would do an Echo series to flesh her out a little bit more. He said, 'It's going to happen one way or another, but you should do an Echo series just to give her more of a back story before that starts happening more." So I said, "Great," and I put this Echo story together. Then I had a meeting with him in the office in New York, and he sat me down and said, "I know you wanted to do this Echo story, but we're going to put it inside the panels of Daredevil. That way, it'll give the regular team an extra five months to catch up and get ahead on things. He said, "Our Echo story was in there before, so I think it'll still work. We did this before, and it'll be like another fleshing out of Echo. If you could have a scene at the beginning and a scene at the end with Daredevil talking to Echo, that'll segue it.'

That was purely a publishing situation, so I can't fault anyone for that. But, as you've said, when someone's reading a Daredevil comic that's says "Daredevil" on it really big, they're expecting to see Daredevil, and he's really not in that story. I understand that could be a jarring situation for people because the main thing you want to get out of that comic is Daredevil. This story has a scene of Daredevil talking to Echo in the first issue and then one in the last issue, and he was there, here and there, through flashbacks. But I understand somebody feeling that, when they're buying a Daredevil comic, they're not trying to buy an Echo story. But that's just the way it worked in that situation.

It was an interesting experiment. People are probably more willing to accept a change from the mainstream if it's delineated in the title. And I think if people thought, "Oh, there's an Echo story written and drawn by David Mack." It probably wouldn't be as jarring to them. But, because now it's in the Daredevil series, there were a lot of people who loved it, and there were a lot of people who probably didn't know why those issues were featuring an Echo story in between the current Daredevil story. In comic books, there's brand new readers every issue. Those people were probably asking, "What's going on? There was a Daredevil cliffhanger, and now there's this story about another person. I understand that kind of criticism. I felt like it was able to find its readership, and I find there were a lot of people that connected to it and got something from it.

HJ: Some have compared Vision Quest with Bill Sienkiewicz's Elektra: Assassin, which also applied avant-garde techniques to this particular franchise. Was this a parallel that occurred to you as you were working on this book? If so, how would you compare your work with Sienkiewicz's?

DM: I have a very good relationship with that book. In fact, I'm pretty good friends with Bill Sienkiewicz now, and I was having a conversation with him about this just last night. He's been super nice to me, but I was probably pretty young when I read that. I was probably 11 or 12 when I saw that first Elektra: Assassin book, and I was fascinated by it. It was beyond my experience. It was beyond my comfort zone. So, at first, maybe I wasn't sure what to think of it, but then I really appreciated it.

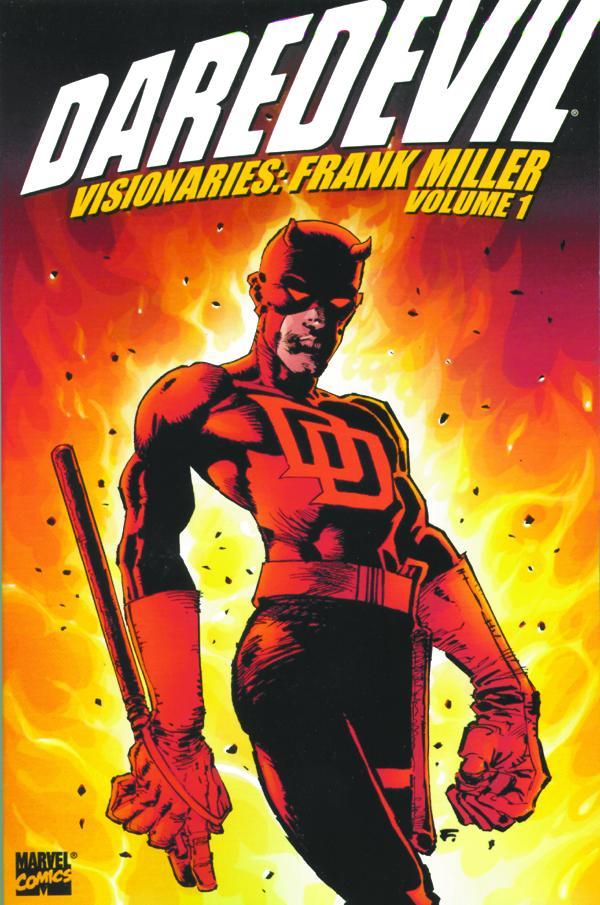

The first Daredevil story I ever read was a Frank Miller story. It was that one with The Punisher in it, from an "Angel Dust" story, in maybe 1982. I was at a friend's house, and they had this comic book. I had never read a comic book. I was nine years old. I open up this book, and I thought that comics would be like Super Friends. So, it was one of those things where it was expectations versus what something is. I had seen some cartoons here and there at friends' houses. So, I pick up his comic book and, instead of someone in a cape with a letter on their chest, there's a guy dressed as a devil with horns on his head as the hero, and there was another guy with a skull on his chest just shooting people. It was almost frightening to me as a child. It was a story about drugs and angel dust, and children were selling drugs to children and dying. It was really outside my comfort zone. I wasn't sure what to make of it.

Then, in some strange turn of chance maybe two or three years later, I was in a second-hand store--a St. Vincent De Paul--and I found the exact next issue of that book. By then, I was like 12 years old, and I picked it up. I could handle it then. It made sense to me. I saw the brilliance in it, and I loved it. Then, I started trying to find back issues of Frank Miller's Daredevil, and there was something about those issues that I can never escape that probably informs my work in ways that I'll never even be conscious of.

I remember being in the secondhand store, looking at this book and realizing that someone made these shadows and this lighting and that the shapes of the panels were all designed by the writer on purpose because they were communicating something. I thought it would be all bright colors as a kid, and I realized all these shadows and all this very iconic kind of architecture to this book was making me feel something. I think that's when I clicked for me, that the writer can use all of this--the weather, lighting, shadows--as storytelling.

I had similar experience in a different way when I saw the Elektra: Assassin books. All those people that I have been inspired by...there's a great many. Comic books have a great many giants. I think, when you're doing something in a medium that has all these wonderful people before you, it's up to you to stand on the shoulders of those giants and then try to bring something of your own to it as well.

MORE TO COME