Comics from the 19th to the 21st Century: An Interview with Jared Gardner (Part Two)

/Your book contributes in important ways to recent efforts by a number of comics scholars to reconsider Frederic Wertham not simply as a public crusader against comics, but as perhaps the first critic to take comics seriously as a medium with its own aesthetic and reading practices. What do you think more recent work about comics as a medium might learn through this reconsideration of Wertham?

Wertham's demonization by comics history makes a certain amount of sense, even as it often requires gross oversimplification of his important if flawed book. More troubling to me has been Wertham's virtual erasure from the history of media studies. In histories of the field, if he is mentioned at all, it is only as a McCarthyite bogeyman, which couldn't be further from the truth. This is, after all, the same man who would write the first study of fanzines, the first psychologist to set up a free clinic in Harlem, and a passionate defender of "juvenile delinquents" against a judicial system he saw as destructive and often unfair, especially for those coming from underprivileged backgrounds.

In the end, Wertham's mistake was an honest one--one originating with his fierce commitment to his patients and his willingness to take comics and his patients' interpretations of them as seriously as they did. Unlike almost any other "expert" witness from the period (the other exception, on the other side of the debate, would be Lauretta Bender), Wertham really took comics very seriously indeed--and recognized their unique hold over the imagination of readers. He understood the ways in which the form made demands upon readers to work to fill in the gaps and spaces--between panels, between word & image--in the process leading to imaginative investments that he found both fascinating and terrifying. Where he went wrong was in imagining that it was the publishers' intention to "seduce" young readers into this intense relationship with comics in order to produce a generation of weak-minded consumers primed for the exploding consumer marketplace of the 1950s (in this way, he is much closer to Adorno than to any of the other contemporary critics of the comic book). He did not yet understand that it was the form itself that uniquely generated this intense and collaborative relationship between reader and creator.

One thing that surprised me as I read the book (and frankly thrilled me) was your ongoing emphasis on the relationship between fanzine publishing and the history of comics. What functions have comic fanzines played through the years?

This was perhaps the biggest surprise for me as well, and one that ended up guiding a lot of my research and thinking over the past decade. I early on noticed that long before the emergence of anything we might call a "fanzine," the earliest comics creators began their careers imitating their favorite cartoonists and came to New York or San Francisco with a portfolio in hand of their best examples--and often made their first sales peddling some of this fan work work on the streets. Many of us read a remarkable novel or see a special film and think: "Hey, I want to do that!" But the concentrated labor involved in plotting and writing a novel and the technical and financial logistics involved in making a movie (at least until fairly recently when we all have movie cameras in our pockets) discourage all but the most determined and fanatically inspired.

Comics however have always invited audiences to pick up a pencil and try it themselves: from the earliest days of the form creators and publishers have encouraged readers to send in their stories, their sketches--even offering how-to guides for drawing favorite characters. The fanzine phenomenon in comics began with scrapbooks in the 1920s: readers clipping their favorite serial strips from newspapers and assembling their own collections of what would otherwise be an ephemeral medium. Scrapbook clubs developed around the most popular strips, and readers often sought out the mediation of the cartoonist himself to help them track down missing installments.

In a way, the history of comics is the history of fan art and the fanzine. Walt Kelly describes himself endlessly peddling versions of Percy Crosby's Skippy before he finally found his way to Pogo. Siegel & Shuster's Superman began as fan art, growing out of their shared love for the newspaper comic strip action hero and the new world making possibilities opened up by the early science fiction pulps. And of course the majority of the cartoonists we associate with the underground movement of the 60s began making fanzines.

And this is what ultimately brought Wertham to fanzines toward the end of his career. If Seduction of the Innocent was all about the dangers posed by the intense interactive experience of making meaning out of comics, Wertham's research on fanzines told the other side of the story he had not acknowledged in his earlier work: of the ways in which comics summoned readers to become creators themselves.

Of course, Wertham could fairly safely celebrate fanzines in the 1970s, when their role in the creation of underground comix was clear for all to see. In fact, in the early 1950s, Wertham and other opposed to comics were targets in some the earliest publications to explicitly define themselves as comics fanzines--especially those devoted to EC, such as Bhob Stewart's pioneering EC Fan Bulletin. Bill Gaines, the publisher of EC, liked the idea of Stewart's fanzine so much he essentially borrowed the title and the format for his own official fan club publication. But while Gaines intuitively understood the importance of nourishing a deep and interactive relationship with his readers in a way no one in comic books had or would again until Stan Lee in the early 1960s at Marvel, Gaines somehow completely missed the opportunity to summon those fans into action through their various local fan clubs and fanzines until it was far too late. Many historians of the form suggest it was simply denial on the part of Gaines and other publishers as to the seriousness of the forces being arrayed against them. But I suspect it had more to do with the lack of seriousness with which they took their own readers and their fan publications, at the end of the day--even as EC which prided itself on its loyal readers.

In the end, of course, the publishers lost (all except a small handful who were poised to profit on the newly mandated "safer" content), but the fanzines continued, with more fanzines devoted to EC emerging after the demise of the comic book company than existed during its lifetime. And the fanzines carried the energy, community, and possibilities of comics across the deadzone of the Code era and into the new frontiers of underground, alternative, and independent comics in the 60s, 70s, and 80s.

I was especially interested in the emphasis in your account of contemporary comics on themes of collecting. As you note, many key comics creators have been collectors not only of comics but also of other ephimeral media, especially of other print culture, from post-cards to pulp novels. What influence has their collecting practices had on the themes and style of their books?

Collecting and OCD! As someone who has more than a touch of both in my genes, I suspect it is one of the things that first attracted me to the form.

Art Spiegelman suggested once that he learned the disciplines of the form--arranging a complicated assortment of often mismatched symbols and signs in a contained space--from his father, a Holocaust surviver, who had taught him how to pack a bag quickly. Comics is the art of the suitcase: never enough space for all that needs packing. And that surely is part of the attraction of cartoonists to collecting (and interesting, again remarking on the negligible distance that separates creators from readers of comics, the same is famously true for comics readers as well). But it is also the art of leaving out and leaving behind. So collecting, the fantasy of completion, of not having to leave anything behind, is perhaps also a necessary salve to the daily sacrifices of cartooning.

Late in the book, you use the concept of the "database" taken from digital media to describe the structure of some recent comics. To what degree do you think the works of artists such as Chris Ware have been influenced by the model of digital media? Did you get to see the interactive comic Ware published recently through the McSweeney iPad app?

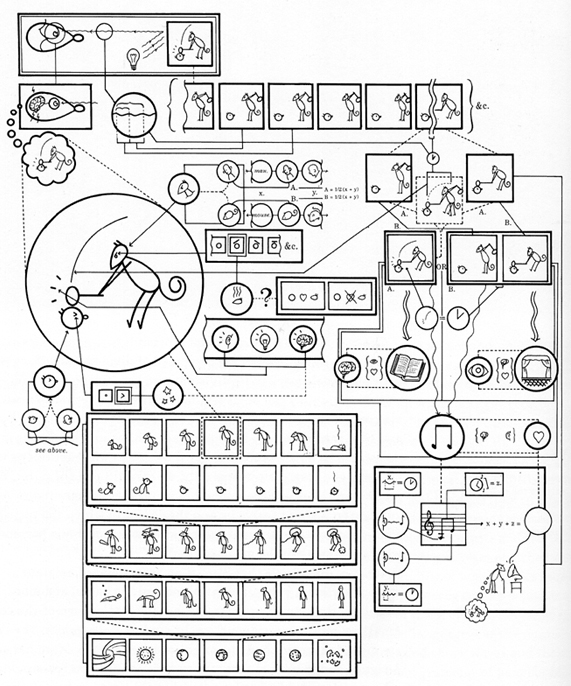

I am fairly certain that Ware would deny any influence from digital media, even as I see his iPad experiment as precisely the kind of work we need more of to make the transition of comics into digital platforms a productive one. Like so many of his contemporaries in alternative comics, he has been fairly outspoken in his skepticism about computers and digital utopias, despite using many digital tools himself in his own work. And yet, it is impossible to look at something like this page from Jimmy Corrigan and not see it as a powerful visual representative of what Manovich and others call the database aesthetic. Here, Ware is describing the work two simple panels from a comic require of a reader, fanning out on the page the range of choices and systems from which the reader will make determinations (in the blink of an eye and/or obsessively, repetitively over time) as to how to fill in the gaps between and bring the story "to life." I can't help here but see something like Peter Greenaway's Tulse Luper Suitcases, where Greenaway leaves on the screen the 'leftovers' from earlier takes, screen tests, and narrative pathways not taken.

Of course, the difference is important, and perhaps it gets to the heart of the difference between comics and film, even film at the hands of the man who is arguably the Godfather of the database aesthetic in cinema. Ware's focus here is on the work of the reader--the database of association, assumptions, memories, icons and signs with which the reader works to activate the comic. Greenaway's ambitious and highly interactive Tulse Luper experiment can offer on the screen the visible outlines of the database from which he drew in making the film. I am going that one step too far that will get me in trouble with my film studies colleagues, I know, but in the end, film, at least as its developed in the western narrative tradition, offers far fewer spaces for agency and interaction on the part of the spectator. Comics, for better and worse, always have to meet the reader (and her database) halfway.