Man Without Fear: David Mack, Daredevil, and the Bounds of Difference (Part One)

/Last fall, I delivered one of the keynote talks at the Understanding Superheroes conference hosted at the University of Oregon in Eugene. The conference was a fascinating snapshot of the current state of comics studies in North America. It was organized by Ben Sanders to accompany a remarkable exhibit of comic art hosted at the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art -- "Faster than a Speeding Bullet: The Art of a Superhero," . The exhibit consisted of original panels scanned the entire history of the superhero genre - from its roots in the adventure comics strips through the Golden and Silver age to much more contemporary work. The conference attracted a mix of old time fan boys whose interests were in capturing the history of the medium and younger scholars who applied a range of post-modern and post-structuralist theory to understanding comics as a medium. In between were several generations of superhero comic writers and artists who brought an industry perspective to the mix. Charles Hatfield delivered a remarkable keynote address talking about the technical sublime in the work of Jack Kirby and my keynote centered on the fusion of mainstream and experimental comics techniques in the work which David Mack did for Daredevil.

The presentation was really more of a talk than a paper so it's taken me some time to get around to writing this up, but I had promised some of my readers (not to mention Mack) that I would try to share some of the key ideas from the talk through my blog. A number of readers have asked about this piece so I appreciate their patience and encouragement. In honor of Comic-Con, where I am, as you read this, I am finally sharing with you my thoughts about David Mack's Daredevil comics.

Images from Mack's work here are reproduced by permission of the artist. Other images are reproduced under Fair Use and I am willing to remove them upon request from the artists involved.

This paper is part of an ongoing project which seeks to understand what a closer look at superhero comics might contribute to our understanding of genre theory. Several other installments of this project have appeared in this blog including my discussion of superheroes after 9/11 and my discussion of the concept of multiplicity within superhero comics.

At the heart of this research is a simple idea: What if we stopped protesting that comics as a medium go well beyond "men in capes" and include works of many different genres? No one believes us anyway. And on a certain level, it is more or less the case that the primary publishers of comics publish very little that does not fall into the Superhero genre and almost all of the top selling comics, at least as sold through specialty shops, now fall into the superhero genre. It was not always the case but it has been the case long enough now that we might well accept it as the state of the American comics industry. So, what if we used this to ask some interesting questions about the relationship between a medium and its dominant genre? What happens when a single genre more or less takes over a medium and defines the way that medium is perceived by its public - at least in the American context?

One thing that happens, I've argued, is that the superhero comic starts to absorb a broad range of other genres - from comedy to romance, from mystery to science fiction - which play out within the constraints of the superhero narrative. We can study how Jack Kirby's interests in science fiction inflects The Fantastic Four and other Marvel superhero comics in certain directions. We can ask why it matters that Batman emerged in Detective Comics, Superman in Action Comics, and Spider-Man in Astounding Stories.

But second, we can explore how the Superhero comic becomes a site of aesthetic experimentation, absorbing energies which in another medium might be associated with independent or even avant garde practices. And that's where my interest in David Mack comes from, since he is an artist who works both in independent comics (where he is associated with some pretty radical formal experiments in his Kabuki series) and in mainstream comics (where he has made a range of different kinds of contributions to the Daredevil franchise for Marvel.)

Certainly, most comic books fans understand a distinction between underground/independent comics and mainstream comics but there is surprisingly fluid boundaries between the two. In many ways, independent or underground comics were often defined as "not superhero" comics and therefore still defined by the genre even if in the negative. Throughout this essay, I am going to circle around a range of experiments which seek to merge aspects of independent comics with the superhero genre.

My primary goal here is to map what David Bordwell, Janet Staiger and Kristen Thompson describe in Classical Hollywood Cinema as "the bounds of difference." Bordwell, Staiger and Thompson draw on concepts from Russian formalism to talk about the norms which shape artistic practice and the ways they get encoded into modes of production. By norms, we mean general ways of structuring artistic works, not rigid rules or codes. Norms grow through experimentation and innovation. There is no great penalty for violating norms. Indeed, the best art seeks to defamiliarize conventions - to break the rules in creative and meaningful ways and in the process teach us new ways of seeing.

Genres are thus a complex balance between the encrusted conventions, understood by artists and consumers alike, built up through time, and the localized innovations which make any given work fresh and original. The norms thus are elastic - they can encompass a range of different practices - but they also have a breaking point beyond which they can not bend. This breaking point is what Bordwell and Thompson describe as "the bounds of difference." They have generally been interested in the conservative force of these norms, showing how even works which at first look like they fall outside the norms are often still under their influence. They have shown how the classical system has dominated Hollywood practice since the 1910s and continues to shape most commercial films made today.

In my work, I have been more interested in exploring the edge cases, especially looking at the transition that occurs when an alien aesthetic gets absorbed into the classical system. This was a primary focus of my first book, What Made Pistachio Nuts?: Early Sound Comedy and the Vaudeville Aesthetics and it's a topic to which I have returned at various points throughout my career. In this talk, I want to use David Mack's work for Marvel to help us to map "the bounds of difference" as they impact mainstream superhero comics.

We can get a better sense of why Mack's work represents such an interesting limit case by sampling some of the reviews for Daredevil: Echo - Vision Quest from Amazon contributors, each of whom has to do a complex job of situating this work in relation to our expectations about what a mainstream superhero book looks like:

If you'd like to see Daredevil swinging through New York City beating up bad guys, this is not the comic for you. Although this is technically Volume 8 of the recent Daredevil run, it isn't exactly part of the regular continuity. The five issues that make up this volume were going to be a separate miniseries, but when Bendis and Maleev needed a break from Daredevil (after the Issue 50 battle with the Kingpin), the Echo mini was published under the Daredevil title instead.

This has led to an unfairly bad reputation for this beautifully painted, dream-like exploration of identity and willingness to fight for a cause. Daredevil subscribers expected more of the plot and action that had filled the series to that point, and this meditative break was frustrating, particularly considering the point that Bendis had halted the main plot.

If you are a fan of Alias (the comic) or Kabuki, this is for you. If you would like to gaze in awe at the poetic writing, beautiful painting and stunning mixed-media art of one of the most creative men in comics, buy this comic. You won't regret it.

******************************************************************************************

I think if this had come out as a graphic novel, or as a seperate mini, I may have enjoyed it more. But imagine being engrossed in an intelligent, gritty fast-paced work and then being forcefed an elaborate, artsy character study on a relatively minor character. ... This should have been a seperate mini or graphic novel. Instead we get the equivalent of a documentary on Van Gogh between Kill Bill Volume 1 and 2.

************************************************************************************

This book is a sadistic deviation from thier storyline and is writen and draw by David Mack. This is a (...) crap fest about a very minor character and her hippie like journey to discover her past. ...He then further expresses his impotency in the field by using chicken scratch drawings and paintings to move the story along with hardly ANY dialog. THis book is an artsy load of crap that should not be affiliated with Daredevil or Marvel.

Each of these responses struggles with an aesthetic paradox: Mack's approach to the story does not align with their expectations about what a superhero comic looks like or how it is most likely structured - yet, and this is key, the book in question appears in the main continuity of a Marvel flagship character. There is much greater tolerance as several of the readers note for works which appears on the fringes of the continuity - works which is present as in some senses an alternative, "what if?" or "elseworlds" story, works which more strongly flag themselves as site of auteurist experimentation.

There is even space there for the moral inversion involved in telling the story from the point of view of the villain rather than the superhero: witness the popularity of Brian Azzarello's graphic novels about Lex Luther and The Joker. But Mack applies his more experimental approach at the very heart of the Marvel superhero franchise and as a consequence, the book was met with considerable backlash from hardcore fans who are often among the most conservative at policing "the bounds of difference." Vision Quest is not Mack's only venture into the Daredevil universe: David Mack wrote Parts of a Hole which was illustrated by veteran Marvel artist Joe Quesada; David Mack then contributed art to Wake Up, written by Brian Michael Bendis, perhaps the most popular superhero script-writer of recent memory. In both cases, then, Mack's experimental aesthetic was coupled with someone who fit much more in the mainstream of contemporary superhero comics. The result was a style which fit much more comfortably within audience expectations about the genre and franchise.

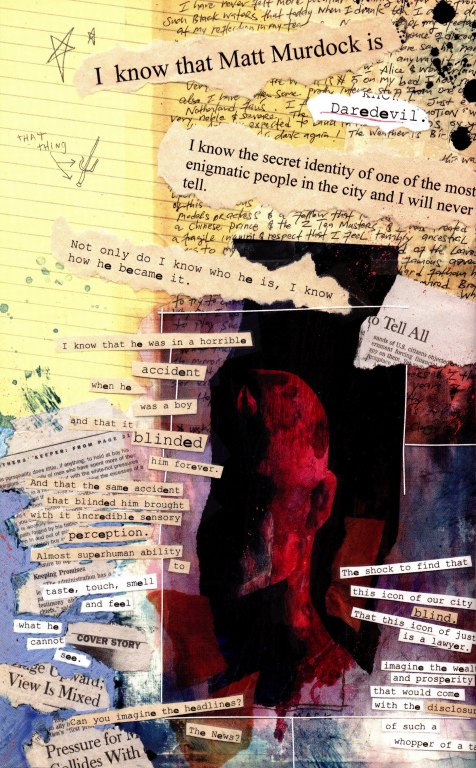

We can see the difference in these two images, the first drawn by Quesada for a Mack Script, the second as drawn by Mack based on his own conception. Both combine multiple levels of texts to convey the fragmented perspective of Echo, the protagonist, as she confronts her sometimes lover, sometimes foe Daredevil. The use of bold primary color and the style of drawing in Quesada's version pulls him that much closer to mainstream expectations, while the deployment of pastels and of a collage-like aesthetic falls outside our sense of what a superhero comic looks like. The subject matter is more or less the same; the mode of representation radically different and in comics, these stylistic differences help to establish our expectations as readers.