On the Pleasures of Not Belonging, or Notes on Interstitial Art (Part One)

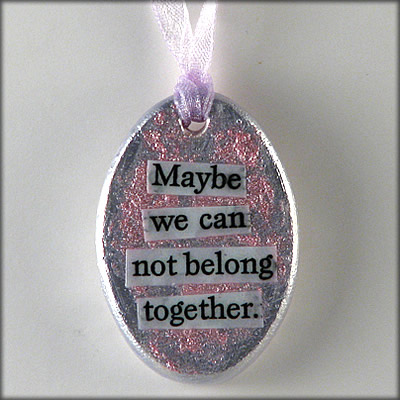

/Last January, I wrote the following essay to run as the foreword for a recently published collection of short fiction -- Interfictions 2: An Anthology of Interstitial Writing -- which was edited by an old friend, Delia Sherman. The essay offers my explanation of what we mean by "interstitial writing" and my exploration of the deforming and informing value of genre in contemporary storytelling. Over the next installments, I will also be featuring an interview with Delia about her goals for the book and an interview with some of the contributors about their relationship to the genre conventions of popular fiction. I am hoping that this series of posts will serve to introduce readers of this blog to the work of the Interstitial Arts Foundation, a really wonderful group of writers and thinkers, who are on the frontiers of contemporary popular fiction. This pendant, inspired by my introductory essay, was produced by artist Mia Nutick as part of an auction being organized around the book. For more, see http://iafauctions.com/

On the Pleasures of Not Belonging

Henry Jenkins, 2009

(Note: The following essay appeared as the introduction to Interfictions 2, the recently-released anthology of interstitial fiction from the Interstitial Arts Foundation.)

"Please accept my resignation. I don't care to belong to any club that will have me as a member."

– Groucho Marx

Let's start with some basic premises:

- I do not belong in this book.

- The contributors also do not belong.

- You, like Groucho Marx, wouldn't want to belong even if you could. Otherwise, you probably wouldn't have picked up this book in the first place.

Let me explain. The editors of most anthologies seek stories which "fit" within prescribed themes, genres, and topics; the editors of this book have gone the opposite direction – seeking stories that don't fit anywhere else, stories that are as different from each other as possible. And that's really cool if the interstitial is the kind of thing you are into.

At the heart of the interstitial arts movement (too formal), community (too exclusive), idea (too idealistic?), there is the simple search for stories that don't rest comfortably in the cubbyholes we traditionally use to organize our cultural experiences. As Ellen Kushner puts it, "We're living in an age of category, of ghettoization – the Balkanization of Art! We should do something." That "something" is, among the other projects of the Interstitial Arts Foundation, the book you now hold in your hands.

Asked to define interstitial arts, many writers fall back on spatial metaphors, talking about "the wilderness between genres" (Delia Sherman), "art that falls between the cracks" (Susan Simpson), or "a chink in a fence, a gap in the clouds, a DMZ between nations at war" (Heinz Insu Fenkel). Underlying these spatial metaphors is the fantasy of artists and writers crawling out from the boxes which so many (their publishers, agents, readers, marketers, the adolescent with the piercings who works at the local Borders) want to trap them inside. Such efforts to define art also deform the imagination, not simply of authors, but also of their readers.

All genre categories presume ideal readers, people who know the conventions and secret codes, people who read them in the "right way." Many of us – female fans of male action shows, adult fans of children's books, male fans of soap operas – read and enjoy things we aren't supposed to and we read them for our own reasons, not those proposed by marketers. We don't like people snatching books from our hands and telling us we aren't supposed to be reading them.

One of the reasons I don't belong in this book is that I'm an academic, not a creative artist, and let's face it, historically, academics have been the teachers and enforcers of genre rules. The minute I tell you that I have spent the last twenty years in a Literature department, you immediately flash on a chalkboard outline of Aristotle's Poetics or a red pen correcting your muddled essay on the four-act structure. Throughout the twentieth century, many of us academic types were engaged in a prolonged project of categorizing and classifying the creative process, transforming it to satisfy our needs to generate lecture notes, issue paper topics, and grade exam questions. After all, academics are trapped in our own imposed categories ("disciplines" rather than "genres") which often constrain what we can see, what we can say, and who we can say it to. Academics are "disciplined" through our education, our hiring process, our need to 'publish or perish', and our tenure and promotion reviews. Most academics read or think little outside their field of study. As Will Rogers explained, "there's nothing so foolish as an educated man once you take him out of the field he was educated in."

I may gain a little sympathy from you, dear reader, if I note that for those twenty years, I was a cuckoo's egg – a media and popular culture scholar in a literature department – and that I am finally flying the coop, taking up an interdisciplinary position at a different institution, because I could never figure out the rules shaping my literature colleagues' behavior.

Many literature professors may hold "genre fiction" in contempt as "rule driven" or "formula-based" yet they ruthlessly enforce their own genre conventions: look at how science fiction gets taught, keeping only those authors already in the canon (Mary Shelly, H.G. Wells, Margaret Atwood, Thomas Pynchon), adding a few more who look like what we call "literature" (William Gibson, Octavia Butler, Philip K. Dick), and then, running like hell as far as possible from any writer whose work still smells of "pulp fiction." Here, "literature" is simply another genre or cluster of genres (the academic mid-life crisis, the coming of age story, the identity politics narrative), one defined every bit as narrowly as the category of films which might get considered for a Best Picture nomination. I never had much patience with the criteria by which my colleagues decided which works belonged in the classroom and which didn't.

What I love about the folks who have embraced interstitial arts is that some of them do comics, some publish romances, some compose music, some write fantasy or science fiction, but all of them are perfectly comfortable thinking about things other than their areas of specialization. In that sense, I do very much belong in this collection as a kindred spirit, a fellow traveler, both phrases that signal someone who does and does not fit into some larger movement. Maybe we can go to each other's un-birthday parties and not belong together.

To be sure, academics are not, as Buffy would put it, "the big bad." We may have gotten inside your head but with a little mental discipline, you can shove us right back out again. Most interstitial artists ritually burned their old course notebooks years ago. They started to write the stories they wanted to be able to read, only to be told by their publisher that their book would sell much more quickly if it could be positioned into this publishing category for this intended audience and to achieve that you just need to cut back on this, expand on that, and add a little more of this other thing. I often picture James Stewart in Vertigo gradually redressing, restyling, and redesigning Kim Novak's entire identity, all the while creepily asserting that it really shouldn't make that much difference to her. That's the process those of us who sympathize with the concept of interstitial arts are trying to battle back into submission or at least push back long enough so that we can demonstrate that there are readers out there, a few of us, who want the stuff that doesn't really fit into fixed genres, though it may bear some faint family resemblance to several of them at once. Viva the mutts and the mongrels! Long live the horses of a different color!

So, you are now about to enter the Twilight Zone, where nothing your freshmen literature teacher taught you applies, where we eat with the wrong forks and wear white shoes after Labor Day. But it doesn't mean that academic genre theory has nothing to contribute to our efforts as readers and writers to step across the ice floes and navigate the shifting sands of the interstitial. For the next few pages, I will be proposing a more contemporary account of how genre works in an era where so many of us are mixing and matching our preferences and defying established categories. The work of genre is changing as we speak – in some ways becoming more constraining, in others more liberating – and genre theorists are rethinking old assumptions to reflect the flux in the way culture operates.

To start with Genre Theory 101, all creative expression involves an unstable balance between invention and convention. If a work is pure invention, it will be incomprehensible – like writing a novel without using any recognizable language. Don't worry: a work that is pure invention is only a theoretical possibility. None of us, in the end, is all that original; we borrow (often undigested) bits and pieces from the already written and the already read; we all construct new works through appropriation and transformation of existing materials. As Michel Bakhtin explains, we don't take our words out of the dictionary; we rip them from other people's mouths and they come to us covered with the saliva of where they've already been spoken before. Sharing stories is swapping spit.

However, If a work is pure convention, it will bore everyone. While most of us feel gratified when a work sometimes meets our expectations and most of us feel somewhat frustrated when a work fails to deliver those particular pleasures we associate with a favored formula, none of us wants to read a book that is predictable down to the last detail. All artists fall naturally somewhere on the continuum, in some ways following the dictates of their genres, in other ways breaking with them. And most readers pick up a new book or video expecting to be surprised (by invention) and gratified (by convention).

As they seek to satisfy our desires for surprise and gratification, genre conventions are both constraints (like strait jackets) and enabling mechanisms (like life vests). They are constraints in so far as they foreclose certain creative possibilities, and they are enabling mechanisms in so far as they allow us to focus the reader's attention on novel elements. In the Russian formalist tradition that shaped my own early graduate education, we didn't speak of "rules"; we spoke of "norms," with the understanding that a work only achieved its fullest potential when it, in some way, "defamiliarized" our normal ways of seeing the world and ordering our experience. Or in another familiar paradigm, the auteur critics embraced those filmmakers who were "at war with their materials," that is, who followed the expectations of genre just enough to continue to be employed by the Hollywood studio system but also sought to impose their own distinctive personality by breaking as many of those rules as possible.

Now, let's consider how some of the writers featured on the Interstitial Arts Foundation website are confronting these competing pulls towards convention and invention as they think about their work. Some are seeking to break with the conventions of genre more dramatically than others; they each lay claim to different positions on the continuum between convention and invention.

Here, for example, is Barth Anderson: "If the work comforts, satisfies, or generally meets the expectations that viewers might carry of a genre in question, then the work is genre. This might even apply to works attempting to redefine genre or works which introduce alien elements and disciplines into the genre mix... Interstitial art should be prickly, tricky, ornery. It should defy expectations, work against them, and in so doing, maintain a relationship to one or more genres, albeit contentiously.... Interstitial art is often upsetting. It rocks worldviews, political assumptions, sacred cows, as well as bookstore shelves." Anderson values surprise and sees genre primarily as a constraint.

Susan Stinson, by contrast, sees the artist as moving between the pleasures of operating within genres and the freedom of escaping their borders: "The gifts of being in a genre – reading the same essays and stories; seeking out the same mentors; publishing with the same magazines and presses; writing books that share shelf space; gathering at workshops, retreats, and conferences often enough to know each other – create a common language... I've felt both embraced and constricted by the conventions of those worlds.... The interstitial idea of thriving in cracks and crevices feels like [another] kind of home. Nurturing active, creative, receptive, demanding relationships and institutions that welcome genre-bending and respect a wide range of sources, traditions, and affinities sounds so good that it scares me. The expanded possibilities for joy are worth the risks." Stinson acknowledges the gratifications of consuming genre entertainment and understands genre formulas as both enabling mechanisms and constraints.

Anderson speaks about the interstitial as "prickly, tricky, ornery," while Stinson sees it as welcoming, "nurturing," joyous, and "receptive." One stresses radical breaks from the genre system, while the other is negotiating a space for singular passions within the system.

MORE TO COME