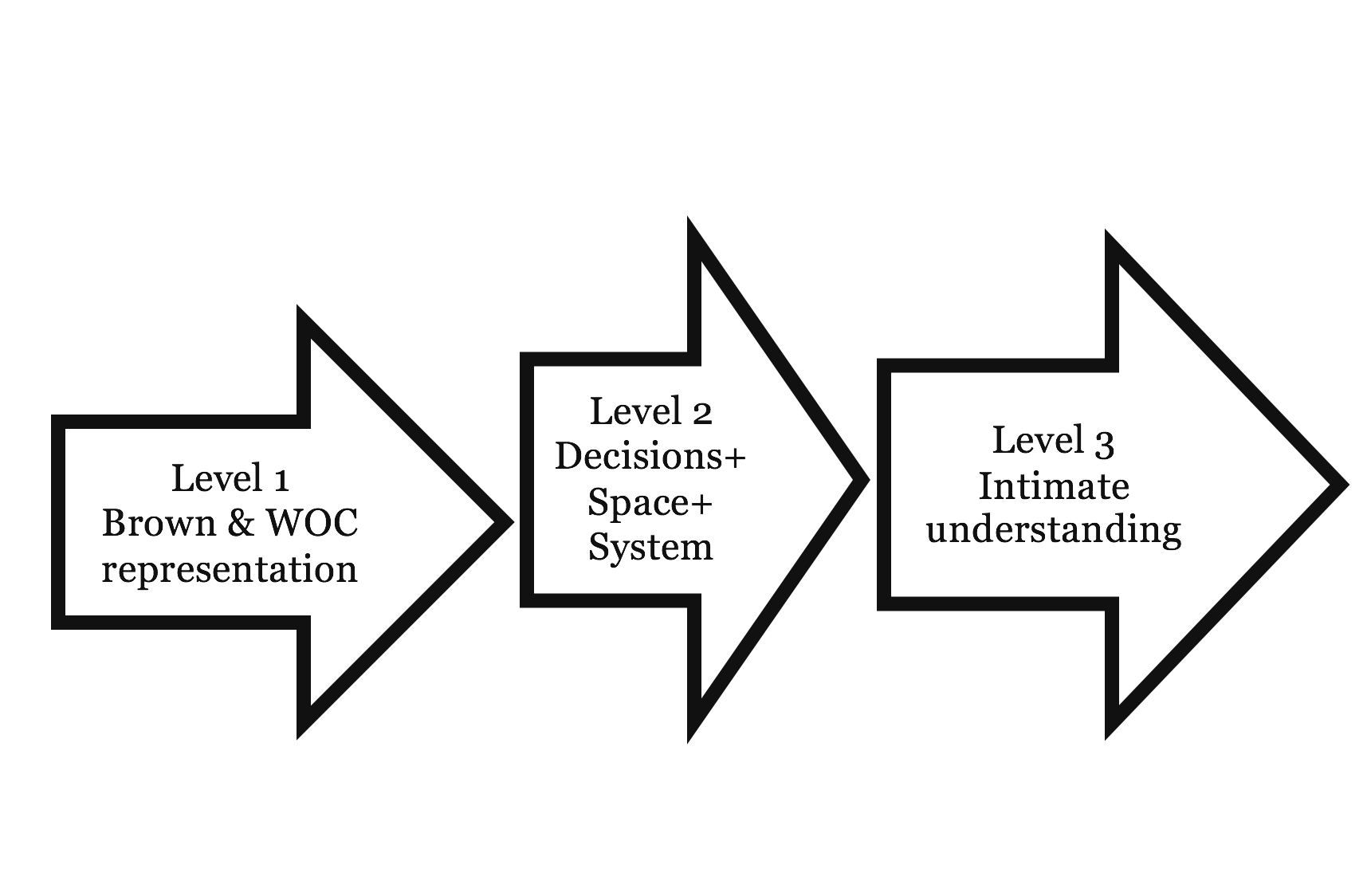

Framing Dreams and the Technological Uncanny (Part Two)

/This is the second part of an essay written by Mina Kaneko for my PhD seminar on Medium Specificity. Satoshi Kon's Paprika

Still from Paprika, by Satoshi Kon.

Satoshi Kon’s 2006 anime Paprika takes a different approach to media and technology, primarily in that dreams are the subjects to be mediated, and notions of the “frame” or “virtual window” are used as tropes within the narrative. The story, based on the science-fiction novel of the same name by Yasutaka Tsutsui, is centered on a thin, glowing headset called the DC Mini, which allows a person to enter and record another person’s dreams. Intended for psychotherapy use, the DC Mini is not yet a perfected technology—and a knowing thief perverts its functions to invade and control the minds of the greater human population. As havoc is wreaked—at first gradually, then suddenly—a collective dream overtakes the city of Tokyo, which is overwhelmed by gigantic puppets and dolls, creatures and statues. It is up to a talented psychotherapist named Chiba and her alter ego Paprika to save the world from destruction.

The DC Mini is, more than anything, an immersive technology, the kind of “fanciful extrapolation of contemporary virtual reality” described by Bolter and Grusin in their essay “Remediation” (313). Bolter and Grusin describe what they call “the logic of immediacy” in a media experience like VR, which is “immersive” because of the perceived invisibility of the technology—it strives to “foster in the viewer a sense of presence: the viewer should forget that she is in fact wearing a computer interface and accept the graphic image that it offers as her own visual world” (314). An example of such a device is the subject of the film Strange Days, by Kathryn Bigelow (1995). “The wire” has brain sensors that enable the recording and delivery of direct sense experiences from one person to another. It’s appeal, Bolter and Grusin write, lies in the fact that it “bypasses all forms of mediation and transmits directly from one consciousness to another,” making it “the ultimate mediating technology, despite or indeed because the wire is designed to efface itself ” (311-312).

The DC Mini. In the opening scene, Paprika says, "It's the scientific key that allows us to open the door to our dreams."

The DC Mini. In the opening scene, Paprika says, "It's the scientific key that allows us to open the door to our dreams."

Strikingly similar to the wire, the DC Mini is a wearable headpiece with sensors that pick up signals from a user’s brain while asleep—they are then transmitted to another user who is also wearing a headset. This allows the therapist using the device direct access to a patient’s dreams, in “real time,” as they are experiencing them. This is apparent in the opening scene, in which Paprika treats a new patient we later learn to be a detective named Konakawa. We are first shown a dream about a mysterious circus, in which Konakawa looks for someone who has betrayed him. Paprika, disguised as a clown, helps him try to identify who it is that he is looking for. As the dream becomes increasingly surreal—Konakawa is put into a birdcage, and a mob of people all resembling himself charge toward him—Paprika assumes different characters, adapting to each shifting moment (an acrobat to help him escape in one, a Jane figure to his Tarzan in the next). Once Paprika puts on the DC Mini, she is in the direct presence of the contents of Konakawa’s dream—there exists no technology, interface, or frame demarcating a boundary to his consciousness. Like the wire in Strange Days, its appeal is that it “bypasses all forms of mediation and transmits directly from one consciousness to another.” While the experience itself is of course mediated by the DC Mini, the DC Mini is the “ultimate technology” because it “effaces itself” once worn. Furthermore, Paprika is not merely a passive observer, but an active participant, able to interact freely with the subjects that emerge within the dream space.

The DC Mini has another essential function, and that is to record dreams to be viewed while outside of the dream space. For example, shortly after Konakawa wakes from his circus dream, Paprika replays it for him on a computer-like device called the “psychotherapy machine,” to which DC Minis are connected. Using a program whose interface resembles a video editing software such as Final Cut or iMovie, she pauses specific moments to ask him for clues to the dream’s meaning. In a different scene later in the film, we also see Chiba and her colleagues watching the machines’ live dream recordings to look for clues about the dream hijacker. Thus the dream is an immersive space that can be entered, but it is also a bound and flattened space to be viewed within the confines of the frame.

colleagues watching the machines’ live dream recordings to look for clues about the dream hijacker. Thus the dream is an immersive space that can be entered, but it is also a bound and flattened space to be viewed within the confines of the frame.

The DC Mini's recording function, as shown on a portable device.

The DC Mini's recording function, as shown on a portable device. In her essay “The Virtual Window,” Friedberg argues that the digital screen has come to serve the same functions once served by the window, which acted as “the membrane between inside and outside” (340). Cinematic and televisual screens in particular have “produced an ingrained virtuality of the senses, removing our experience of space, time and the real to the plane representation, but in form of delimited vision, in a frame” (Friedberg 344). The DC Mini’s cinematic function, with the ability to “embalm” dreamt time (as film theorist André Bazin said of photography and cinema), proves that dreams have a materiality or physicality that can be imprinted, flattened, and contained. The ability to record—to pause, rewind, play, and analyze—something as abstract, elusive, and deeply internal as dreams gives them an order and control, and the cinematic screen acts as a “membrane” with which to observe that psychical space.

These currents—of immediacy and the virtual window—continue to interact with one another in various ways, particularly as the hijacker finds a way to blur the boundaries between the dream life (or mediated object) and reality (the world of mediation). After the DC Minis are stolen, multiple people fall victim to a violent mind-control; a delusional dream takes over their consciousness, and they enter a hallucinatory state that leads each of them to jump out of a skyscraper window. When Chiba later nearly falls victim to the same fate, we see the kind of delusion those earlier victims had experienced. Moments before, Chiba had been investigating her colleague’s office; but a door leads her to a completely different environment of a surreal, abandoned fairgrounds, where the only live presence is a traditional Japanese doll. The doll lures her further into the environment, eventually inviting her to climb over a fence. As her colleague Osanai barely saves her from jumping over it, the environment of the fairground melts away, and we see she is actually hovering over a tall balcony railing (clip 1).

Clip 1. The hijacker's dream overtakes Chiba's reality without the presence of the DC Mini.

Here we are presented with a state in which there is no separation, or mediation, with the objects to be mediated—the dream world has entered the world of reality on its own, without warning. It is a state in which “the objects of representation themselves are felt to be self-present,” and in which the technology has “effaced itself” entirely (she is not even wearing a DC Mini)—but it is not the “blissful state” Bolter and Grusin say we desire in our mediated life (355). It is dystopic, rather than a utopic, in which the absence of mediation and the superimposition of fantasy onto reality have violent, harmful consequences.

As the pervasiveness of this troubling immersion intensifies, the frame is increasingly presented as a “permeable interface” (Friedberg 340). Friedberg says that as the size of the windows in the 19th century grew, “its transparency enforced a two-way model of visuality: by framing a private view outward…and by framing a public view inward” (340). Similarly, Smith describes the presence of dual spaces in thinking about the framed painting as a kind of window; he notes that while frame was originally created to demarcate a specific area of the wall for artwork, thus highlighting the painting’s flatness, that the painting could also “present the image of objects in a created ‘space’ on the other side of the canvas” (222).

In one scene, Paprika attempts to save one of her colleagues who has become trapped in the collective dream. Paprika, who had been monitoring the psychotherapy machines and entering the dream space at will to search for the culprit, soon realizes the culprit is none other than the chairman of her company. When Chairman Inui and his accomplice Osanai see her appear in their nightmarish dream, they try to attack her; Paprika runs down a Victorian hallway, shutting herself in a room adorned with 19th century paintings (clip 2). She searches for a means of escape, and jumps into Gustave Moreau’s 1864 painting Oedipus and the Sphinx. In doing so, her body assumes the painted figure of the Sphinx—moments later, Osanai joins her within the frame, assuming that of Oedipus. The previously two-dimensional scene depicted in Moreau’s painting suddenly becomes a three-dimensional, inhabitable space—Paprika, in the Sphinx’s body, hovers above Osanai with her wings; Osanai throws a spear at her, and she tumbles down into the water below.

In another sequence, moments later, Konakawa has entered his own dream space, and walks into an arena of movie theaters. He chooses a theater playing a film called

Clip 2. Paprika escapes into Gustave Moreau's Oedipus and the Sphinx.

“Paprika,” and upon entering, he sees on the screen Paprika tied to a table, Osanai violating her—a display of Paprika’s parallel, real-time experience in Chairman Inui’s dream, occurring at that moment. In a panic, Konakawa runs straight into the film screen to save her, eventually ripping through it and entering the chairman’s dream on the other side (clip 3). Just as the transparent window “enforced a two-way model of visuality,” Paprika frequently shows how spaces can be inhabited on both sides of the painting or cinematic screen. Beyond a frame that merely demarcates virtuality of “space, time and the real” to the “plane representation,” the screen is a “permeable interface” that allows the traversal of boundaries within as well as between dreams.

Clip 3. Detective Konakawa rips through the film screen at a movie theater in his own dream to cross over into the chairman's dream.

The chairman’s nightmare, which spills into others’ dreams as well as onto reality, eventually becomes an overwhelming spectacle of the kind Angela Ndalianis describes in her essay, “Architectures of the Senses: Neo-Baroque Entertainment Spectacles.” Enlarged objects and characters (including everything from umbrellas, refrigerators, “maneki-neko” cat figurines, Russian dolls, statues of Mary and Buddha) march and dance into the streets, turning the city into a massive parade. As the chaos ensues, Paprika jumps increasingly in and out of frames—once into a TV screen announcing the news, then later into a billboard ad, assuming an equestrian’s body and riding away on a horse only to jump out of an ad on a semi-trailer truck by a boat on a canal. The chairman’s dream, however, has a “neo-baroque logic” to it, in that it “refuse[s] to respect the limits of the frame. Instead it ‘tend[s] to invade space in every direction, to perforate it, to become as one with all its possibilities” (Focillon qtd. in Ndalianis 360). While dreams had previously been a subject of observation and immersion within a controlled space, here they threaten the city by “invading the space in every direction...perforating it, becoming one” with the diegetic reality. The frames through which Paprika jumps still serve as entryways in and out of separate spaces, just as before—however, each traversal of a frame brings her only to another location within the expansive, destructive, parading dream, pointing to a collapse (or at least, ineffectiveness) of the frame against a neo-baroque logic that has imposed itself onto the city. Eventually, the infectious delusion is contained by a supernatural specter of Chiba and Paprika that consumes the chairman’s body. We are returned, in the end, to the previous reality in which dreams are entered upon will, and peace is restored.

Like Strange Days, Paprika presents a “world fascinated by the power and ubiquity of media technologies” (Bolter and Grusin 312). In the final delusional parade scene, we see a group of schoolgirls whose faces are mediated by their cell phone screens (clip 4); similarly, a group of business men’s heads are replaced by flip phones—all recite an incoherent, hysterical chant. They are bizarre, creepy moments that seem to caution against a technologically mediated world in which we are no longer ourselves, but replaced entirely by our devices. This scene is also set against the backdrop of a highly mediated cityscape—the city is unidentified, but it undoubtedly mirrors present-day Tokyo. There is nothing fictional about its rendition of the city itself. And yet we see Tokyo, like the Los Angeles of Strange Days, is “saturated with cellular phones, voice- and text-based telephone answering machines, radios, and billboard-sized television screens that constitute public media spaces” (Bolter and Grusin 312). Paprika itself is not opposed to media and technology—indeed, media (here represented by the dream world) has the power to inform and reform our reality (here through the act of psychoanalysis)—and yet, it offers us a narrative that suggests the achievement of true immersion, and the inability to distinguish our fantasies and innermost desires from reality, has the potential to be dangerous. Immersive media is powerful, but there remains a need for distinction, separation, frames, and borders—for the act of mediation itself.

Clip 4. The chairman's dream becomes a spectacle that overtakes the city of Tokyo.

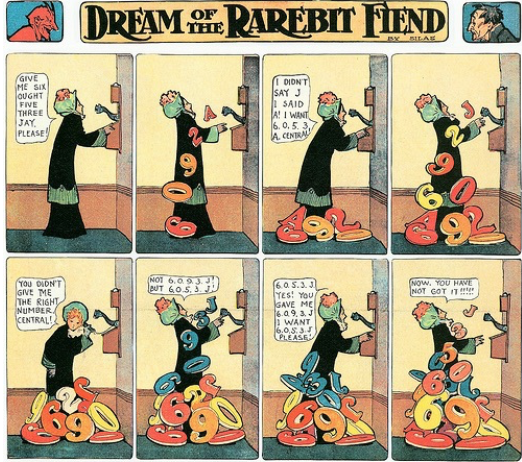

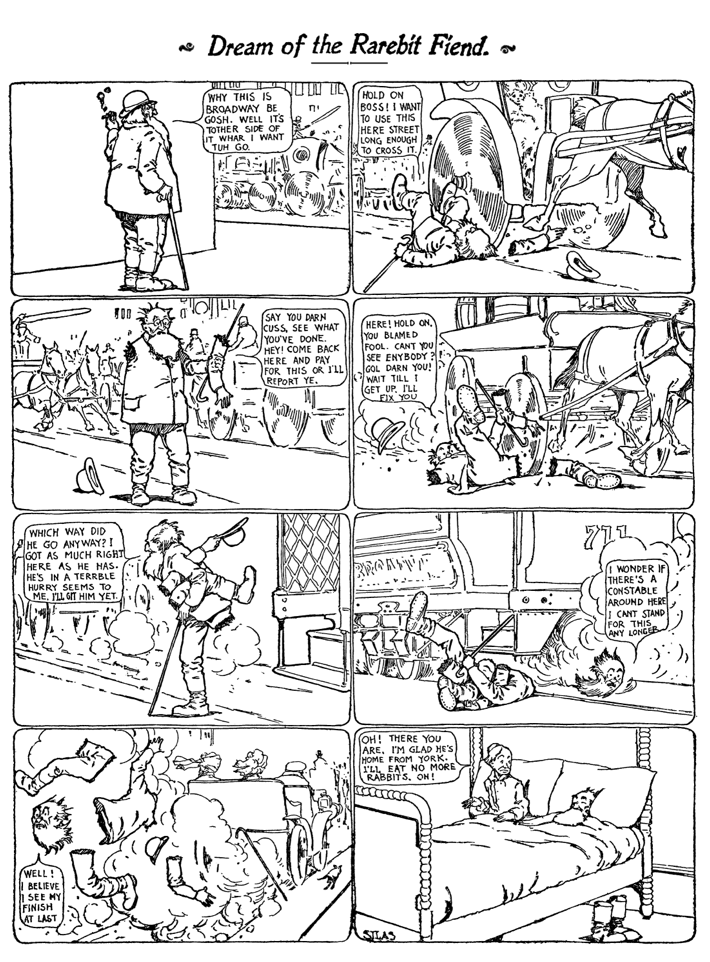

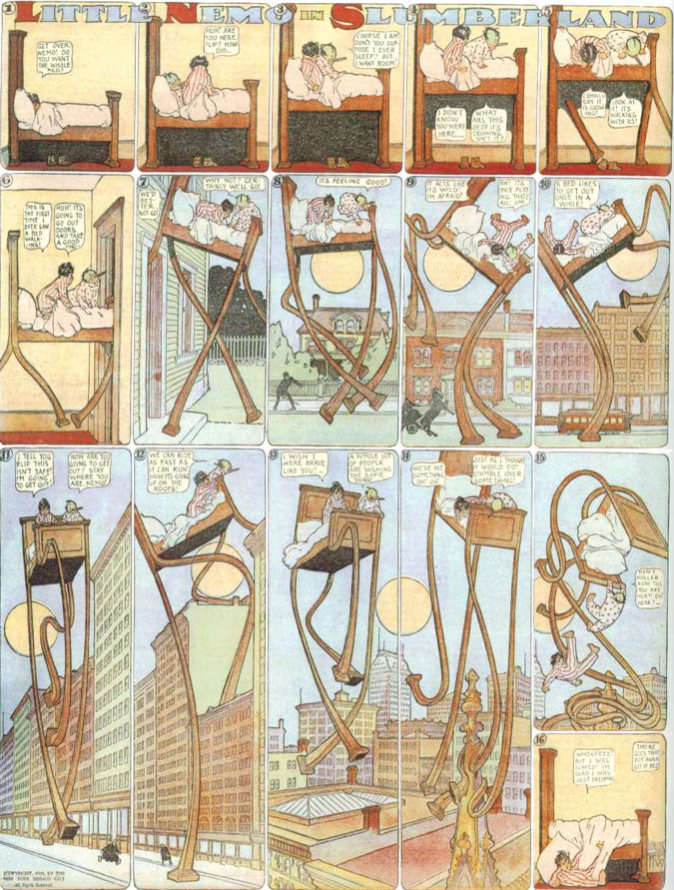

As in McCay's comics, Paprika portrays an urban society abounding with the technological innovations of its period. The ubiquity of televisual screens is a familiar sight for anyone acquainted with Tokyo, presented as a place in which such types of technology have become habituated, or second nature. Like in Rarebit Fiend and Little Nemo, Paprika superimposes fantastical and surreal elements, facilitated by the dream and the unconscious, onto this normalized technological reality, showing a grotesquely transmogrified urban life and defamiliarizing what is familiar. With this wariness comes heightened self-awareness, as Paprika's entrance and traversal of screens intensifies throughout the narrative. Calling attention to the thing we often take for granted, that is, the very boundary that marks the representation within it—we too are reminded that we are watching Paprika the anime, on a screen and within a frame.

In contrast to Rarebit Fiend and Little Nemo, however, Paprika appears to be more focused on the themes of novelty and reception of new technology rather than in the process of habituation. While the malfunctioning technology in McCay's comics are existing technologies, the alluring and perilous technology of the DC Mini is a speculative, fictional one. It is enticing, ground-breaking, addicting, edgy—so new that it hasn't yet been patented. Because it is also a novelty within the diegetic world and not just our own, the anxiety and amazement about it is ever-present in the narrative; neither we nor the characters in the film are accustomed to it. The narrative's suspense rests on this precarious balance between fantasy and fear—from the utopic vision of its ability to alter our psychoanalytic practices (and share dreams from consciousness to consciousness) to the dystopic vision of a city ruined by greed and villainy. Paprika's character embodies this utopia—light, charming, adored, feminine—while the chairman's embodies the dystopia—dark, oppressive, masculine—and the two forces confront each other at the film's climax.

What's compelling about Paprika is that it tells such a story with the medium of anime, with an aesthetic that, like comics, relies on a “strongly stylized, hand-drawn quality,” one which does not try to simulate or replace our three-dimensional world. Unlike “immersive” technologies on which the DC Mini is based and which try to “come as close as possible to the visual world outside,” it presents us with a deliberately two-dimensional, flat world of solid colors (Bolter and Grusin 316). One could say Paprika thus offers a kind of counter-inscription to the kinds of computer-generated aesthetics available to us today and to technologies like VR, instead providing us with a more abstracted, symbolic representation.

At the same time, however, the film immerses us, perhaps even more than it distances us. Unlike McCay, overall Kon does not rupture the aesthetic with different drawing styles; using a consistent visual representation throughout the film, he creates an alternate iconic reality in which the dream materials and the diegetic reality are seamlessly merged. We may not confuse its flatness for our own reality, but the film, with its colorful, luscious drawings, invites us to imagine another one. The anime thus engages us in a different way than some high tech experiences might (something like VR, by operating on the presupposition that it is to assume our reality, often exposes schisms between what's expected and what technology is capable of creating, whereas anime escapes this particular disappointment by speaking through a consciously symbolic representation).

Furthermore, Paprika draws us in by convincing us of the cinematic illusion that the drawn images move. In his book The Anime Machine: A Media Theory of Animation, Thomas LaMarre refers to anime's dialectical relationship with technology, saying it derives its novelty from its “ability to cross between ostensibly low-tech and high-tech situations, to the point that it becomes impossible to draw firm distinctions between low and high tech”—the low-tech being its hand-drawn aspect, and the high-tech being the technologically involved production of animation (xiv). He quotes Norman McClaren's definition:

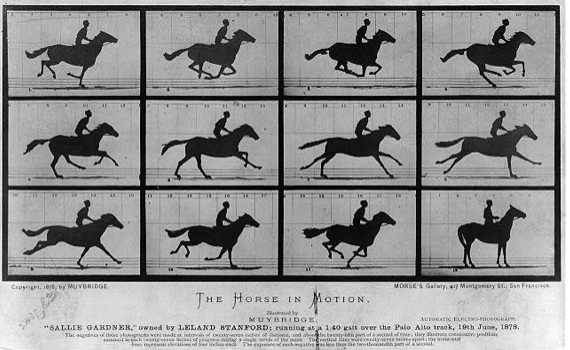

Animation is not the art of drawings that move but the art of movements that are drawn; what happens between each frame is much more important than what exists on each frame; animation is therefore the art of manipulating the invisible interstices that lie between frames. (qtd. in LaMarre xxiv)

While Paprika is reflexive in its metaphorical use of screens, it also seems to embrace its high-tech illusionism. With the exception of a few moments (as when Konakawa enters a movie titled “Paprika”) it rarely breaks the fourth wall, and the construction of anime as the layering of images is never made explicit; the “invisible interstices” that lie between frames remain invisible. Unlike McCay's comics, Paprika never reveals its own process of production, allowing itself to trick us into the illusion that the hand-drawn images with which we are presented do indeed animate. Like the dialectical presence of caution and fascination presented in its narrative, Paprika simultaneously incites critical awareness with its reflexivity while immersing us in technological fantasy.

Framing Dreams and the Technological Uncanny

McCay's Rarebit Fiend and Little Nemo and Kon's Paprika are very different in their visual approaches and evocations of the technological uncanny. In McCay's work, we see an overall wariness about technology and its impact on daily life, which he humorizes in comic form. McCay frequently implicates himself in his process of mediation and exposes the artist behind the fiction. Though he paints captivating dreamscapes in Little Nemo, he also often presents dreams about technology by contrasting the uniformity of the frame with chaotic contents, recalling the negotiation between fear and habituation described by Schivelbusch and Gunning. Paprika, on the other hand, reflects on the novelty of technology, and the utopic and dystopic visions they bring about, through a narrative of science-fiction. It both embraces and cautions against technological innovation, and it is simultaneously reflexive and immersive in its own storytelling.

From Little Nemo in Slumberland, by Winsor McCay.

From Little Nemo in Slumberland, by Winsor McCay.

One could say McCay satirizes anxieties of the "modern" era in which many urban practices were very new, while Paprika responds to a "post-modern" era in which, as Jean Baudrillard wrote, simulation threatens to replace the real—though, terms like "modern" and "postmodern" are most importantly discourses to help think about our present and exist alongside one another. I also agree with Tom Gunning that no matter the era, there is continuity in the emotional and psychical processes we undergo when we encounter new technologies and new media, processes which seem to recur time and time again, whether in response to the magical yet frightful experience of riding a train in the late 19th century, or entering the surreal, virtual portal of the digital screen in our present world.

In their introduction to Rethinking Media Change: The Aesthetics of Transition, David Thorburn and Henry Jenkins also point to the striking parallels between the Victorian age and the so-called Digital Revolution, saying that such moments of cultural transition seem to “generate visions of apocalyptic transformation” as well as those of “technological utopia” (1). There is euphoria and panic at the heart of immense change—but as they note, in reality, change is never so simple or so sudden; media practices shift gradually, in nuanced ways. Furthermore, they write:

The introduction of a new technology always seems to provoke thoughtfulness, reflection, and self-examination in the culture seeking to absorb it. Sometimes this self-awareness takes the form of a reassessment of established media forms, whose basic elements may now achieve a new visibility, may become a source of historical research and renewed theoretical speculation. (Thorburn and Jenkins 4)

Rarebit Fiend, Little Nemo and Paprika are examples of texts that provoke thoughtfulness, reflection, and self-examination about their contemporary moments—ones that "reassess established media forms" and give new visibility to the hand-drawn aesthetic. They present a visual mode of storytelling that departs from the emerging, more novel forms of mediation, be it photography and cinema at the turn of the century, or immersive digital media of the present day. Relying on a visual idiom that needs no referent or original to copy, they highlight a stylistic discursiveness, providing a kind of "counter-inscription" to the subject matter they depict. At the same time, the works show that they too are not without their own technological components, which is sometimes made explicit (eg., in McCay's allusions to the printing presses) and sometimes implicit (eg., in the way Paprika keeps the invisible interstices invisible, but evokes "screen" and "cinema").

Still from Paprika, by Satoshi Kon.

These counter-inscriptive aesthetics also seem to lend themselves well to the subject of dreams. There is a fluidity and versatility with drawing such sites of fantasy and imagination, not least because of its "low-tech" nature that can present an alternate reality as long as it can be drawn; it works without the constraints one might encounter when dependent on more high-tech mechanisms and escapes the expectation of a certain type of presupposed aesthetic. Dreams, in turn, are a rich space in which to explore the uncanny and technology—whether as a site where such anxieties and fears about technologies appear, or as something that seems to mirror new technology and media itself, a site of the unknown future. The frames that figure prominently in these texts—as a window into the fantasy of the unconscious or as an externalized grid or screen that can order and contain—seem themselves to play into the very notion of the psychic layering of the uncanny, in that they mark a metaphorical boundary that controls and habituates our fears, desires, and fantasies—boundaries that just as easily can be collapsed or crossed, letting our apocalyptic and euphoric fantasies slip through.

Mina Kaneko is an editor and scholar. She holds a BS in Media, Culture, and Communication from NYU and was formerly Covers Associate at The New Yorker and Editorial Associate at TOON Books. She is currently a PhD candidate in Comparative Media and Culture at USC, where she is a Provost's fellow. Her research interests include contemporary Japanese and Anglophone literature, comics, and cinema, as well as theories of visuality, psychoanalytic theory, and intersections of race, gender, and sexuality.