One of the many highlights of my first semester in LA was the chance to see and meet Shepard Fairey. who I regard as one of the most significant visual artists of our times and a focal point for debates about the politics/poetics of appropriation and fair use. Fairey spoke on stage with my new colleague, Sarah Banet-Weiser.

I have been following Fairey for some time since he was an art student at the Rhode Island School of Design and "Andre the Giant has a Posse" stickers started to appear on lamp posts and underpasses around Boston. At first, I envisioned the stickers as a new kind of fan art -- since I was deeply into the World Wrestling Federation at the time -- and only gradually came to understand them as a form of culture jamming. Now, having seen and talked with the guy, I suspect they were an odd blurring between the two -- a bold experiment in tapping the power of participatory culture to spread images across the planet and relying on local contexts to shape what those images meant to participants. Pretty cool.

One of the students in my New Media Literacies class last term, Evelyn McDonnell took advantage of Fairey's visit to USC to interview him for the Miami Herald. McDonnell is a cultural reporter of the highest order -- the kind of student you hope you will get at a place where journalism and communications students co-mingle. She's already written three books and edited two more, mostly dealing with rock music, and she's now working on a project dealing with the shifting relationship between artists (popular and high) and their publics. She really dug deep for the Herald story and found out much more than could make it into a newspaper piece, so she asked if she could expand this work as her final paper for the class.

I was certainly intrigued to learn more about her thoughts on Fairey and especially on the current legal struggles he is engulfed in. But what she gave me was so much more -- an exploration of artistic and musical appropriation since the Punk era, how they have shaped Fairey's aesthetic project and how they have impacted the current state of law around Fair Use. Her interest in rock is very visible in the opening which shows how the album design for the Sex Pistal's Never Mind the Bollocks helped to inspire Fairey.

I timidly asked her if she'd be willing to share it via my blogs, knowing that the topics would be relevant to some many different readers, and I was grateful she agreed. I am running the essay in two installments -- today's part takes the long view situating Fairey's work in the larger trajectory of artistic appropriation; the second part, which will run on Friday, deals specifically with the Obama Hope poster, how and why it was created, and the legal battle that now surrounds it. Enjoy!

Never Mind The Bollocks: Shepard Fairey's Fight for Appropriation, Fair Use and Free Culture

By Evelyn McDonnell

Every sk8ter boi with a Clash album and a can of spray paint wants to change the world. In late January 2008, Shepard Fairey may have done just that. Thatʼs when he decided to create something he had never, in some 20 years of producing stickers, T-shirts, prints, stencils, tags, and canvases, made before: a poster endorsing a popular political candidate.

Since Barack Obama was not exactly available to pose for some grassroots graphic artist, Fairey found a photo of the senator online. With a couple mouse clicks, he copied a shot taken by Mannie Garcia in 2006 for the Associated Press. Then he turned a news photo into a propagandist art statement.

Fairey replaced the natural tones of the photo with the strong lines and bold colors -- in this case, red, white, and blue -- of Russian Constructivist art. He added oversized cartoon hatch-mark shadings in the style of Roy Lichtenstein. Across the bottom, he wrote: "Progress." In later iterations, he changed "Progress" to "Hope."

Faireyʼs Obama "Hope" poster is the most iconic, widely seen art work in recent history. Its dignified profile telegraphed both patriotism and change better than any other single image in a mediagenic campaign. "Hope" both captured and helped enable a historic moment.

And it got its maker into a heap of trouble. In ʼ09 Fairey and the AP sued each other over the artistʼs use of Garciaʼs photo. "Hope" may not have merely helped the United States elect its first African-American president. It could set new legal precedents for one of the most important issues of the digital age: intellectual property.

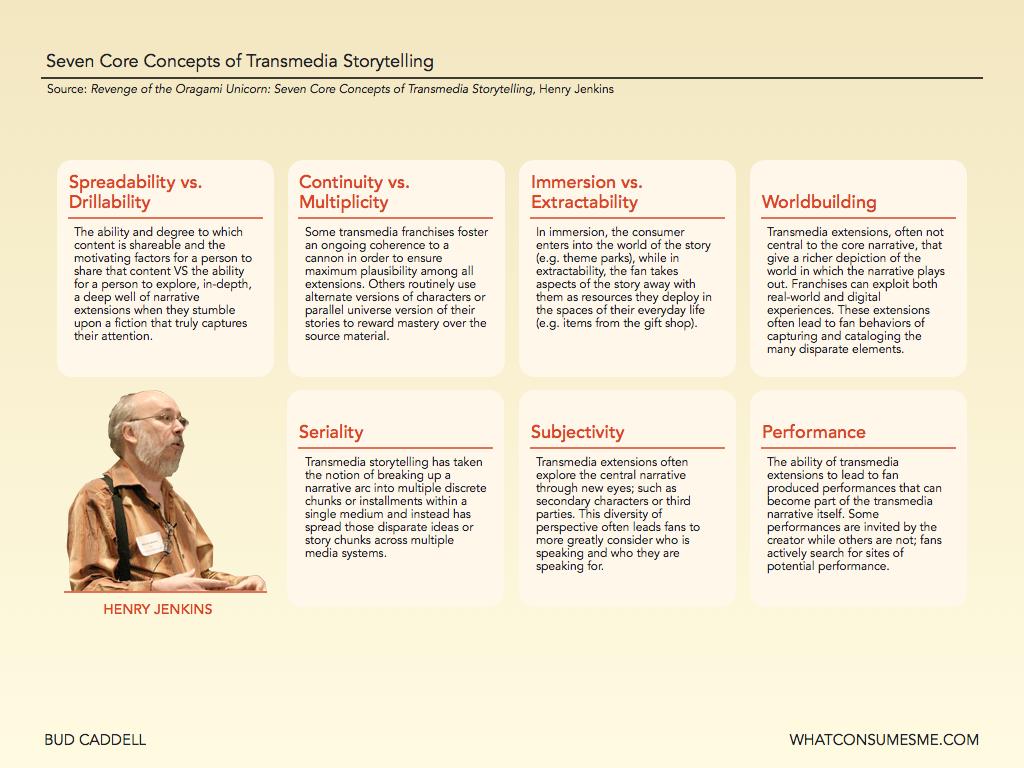

Faireyʼs lawsuits with the Associated Press are a test case for the changing rules of IP and a case study in what media studies scholar Henry Jenkins et al have described as the new media literacy of appropriation.1 The meeting of an underground artist with mainstream and commercial ideology is also an example of what Jenkins calls convergence culture: "a cultural shift as consumers are encouraged to seek out new information and make connections among dispersed media content."2 The story of the "Hope" poster is the story of divergence as well: of increasingly closed copyright law deviating from increasingly open-sourced public practice. In this case, the law and mainstream media are working at odds to both market capitalism and anarchist street culture.

A close analysis of the Fairey/AP battle -- or what could be called the case against "Hope" -- provides key insights into the status of appropriation, fair use, free culture, and engaged citizenry as we enter the final year of the first decade of the 21st century. The battle could be a strategic turning point in what Harvard professor Lawrence Lessig has called the war against free culture. "There is no good reason for the current struggle around Internet technologies to continue," he writes. "There will be great harm to our tradition and culture if it is allowed to continue unchecked. We must come to understand the source of this war. We must resolve it soon."3 By studying Faireyʼs employment of appropriation, we take another step toward understanding that war. Lessig may be optimistic in saying understanding can lead to resolution, but it can certainly inform further activism and creativity.

Anarchy in the Public Domain

Faireyʼs use of Garciaʼs image, and the entire NML conception of appropriation, have historical precedents in the cultural traditions in which the artist was steeped: punk, collage, street art, and Pop art. Frank Shepard Fairey grew up in Charleston, South Carolina. He discovered punk rock and its connected skateboard subculture as a teenager. "The Sex Pistols changed my life," he says. "That was the gateway band for me."4

The English band the Pistols, who sang about "Anarchy in the UK" in a music driven by over-amped guitars and Johnny Rottenʼs sarcastic snarl, were Faireyʼs gateway out of conservative Southern culture and into a global youth subculture characterized by rebellion against mainstream and corporate values. "Thereʼs not a lot of progressive culture there," he has said of his hometown. "I got into the skateboarding and punk life. That opened my eyes to political and social critique: How art could work with things that are political."5

The cover of Nevermind the Bollocks, Hereʼs the Sex Pistols, the bandʼs 1977 debut album, was designed by an English artist named Jamie Reid. Reid did for punk music what Fairey did for the Obama campaign, providing a distinctive iconography of cut-up, Xeroxed images and ransom-note-style lettering. In one famous piece, he put a safety pin through the lip of a reproduction of a photograph of Queen Elizabeth II, providing a visual complement to the Pistols song "God Save the Queen." As far as I can tell, Reid was not sued by royal photographer Peter Grugeon -- though there was certainly intense uproar over the song and artwork.6

There was a purpose to this playfulness. Do-It-Yourself -- the notion that culture should actively

be in the creative hands of the people, not just something produced by corporations and consumed by a passive audience -- is a guiding ethos of punk. In reaction to the showy musicianship of art-rock, such bands as the Clash advocated that music be simplified and demystified, so that anyone could play it. Cut-up art is similarly a way of claiming images that permeate public spaces (the queenʼs face was omnipresent in ʼ77 England, the year of the Silver Jubilee), asserting individual expression over them (the safety pin), and making them public domain (Reidʼs image was stickered around town). Through media bricolage, Reid and other punk ʻzine creators asserted individualsʼ right to exploit and manipulate commercial imagery, since commercial imagery exploits and manipulates the public. They were appropriating, creating visual remixes and mashups -- long before those were digital-culture buzzwords.

The graphic creation that first made Fairey famous in underground circles was also a punk sticker, one that looks strikingly like "God Save the Queen." Fairey went to the Rhode Island School of Design to study illustration. In 1989, he made a stencil of Andre the Giant and added the words "Andre the Giant Has a Posse," plus the wrestler/actorʼs height and weight. He plastered the stickers around Providence enough that a local weekly, The Nice Paper, took note. Soon, the Andre campaign spread to nearby Boston and New York. Fairey sent stickers to friends who put them up wherever they lived. He advertised in punk magazines and sold the stickers by mail order for five cents each.

Within seven years, he had printed and distributed a million of them. Fairey also made Andre posters and stencils. André René Roussimoff died in 1993, but he and his make- believe posse were ubiquitous on urban street lamps and walls for years afterwards.7

According to one news account, Fairey had to alter the image of Andre, as the owners of World Wrestling Entertainment threatened to sue over it.8 The face evolved into a Constructivist-inspired abstraction, and now the words just said "Obey" or "Giant." The forced change actually enabled Faireyʼs art to become more sophisticated and distinctive. The style that was to become famous with "Hope" was apparent in the "Obey" series of works of 1995.

In his street-art campaign, Fairey was inspired by another musical culture of the 1970s. Graffiti is considered one of the four main elements of hip-hop (the other three being DJing, breakdancing, and rapping). It, like punk cut-up art, is also an assertion of the individualʼs right to self-expression in the public domain, with the legal concept of public domain meant quite tangibly -- on subway cars and abandoned buildings. The art of spray-painting tags (aliases of graffiti artists) and street murals exploded during New Yorkʼs fiscal crisis, as colorful balloon letters and stylized characters proliferated. Such practitioners as Futura 2000, Rammellzee, Lady Pink, Revs, Cost, and Claw became famous for going "all-city."9 Street artists Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat were also accepted into the world of fine art, becoming celebrities of the Downtown scene of the 1980s.

Fairey saw this work all around him on a 1989 visit to New York, shortly before he launched the Andre sticker. "I saw graffiti in risky places that gave me new respect for the dedication of the writers," he writes in Obey: Supply and Demand: The Art of Shepard Fairey. "Stickers and tags coated every surface in New York City. I left the city inspired ..."10

Reclamation and transformation of commercial or public images is also an accepted method in the art world of museums and galleries. Marcel Duchamp virtually invented conceptual installation art with his famous urinal sculpture. Robert Rauschenbergʼs combines and collages of the ʻ50s mixed found objects and images. In the 1960s, Andy Warhol made brightly colored silkscreens of Campbellʼs soup cans, Marilyn Monroe, and Elvis Presley. In the ʻ70s Richard Prince rephotographed commercial shots of Marlboro Men and Brooke Shields.

Such appropriative art has been both highly successful -- a Prince work sold for $1.2 million in 2005 -- and controversial: He was sued over the Shields shot, and reportedly settled out of court for a small fee.11 Still, appropriation has become largely accepted as an artistic practice. "Good artists borrow, great artists steal," Pablo Picasso is reputed to have said. In 2009, Miamiʼs Rubell Family Collection named an exhibit of 74 of its artists engaged in various forms of mimickry, including Mike Kelley, Rashid Johnson, David Hammons, Paul McCarthy, and Sherrie Levine, "Beg Borrow and Steal." "Artists are acting as cultural curators; through their work theyʼre recurating history and recontextualizing it," says Jason Rubell, one of the exhibitʼs curators. "Theyʼre appropriating and reassessing imagery that came before."12

In the same way that Reid and the punks utilized it, appropriation by fine artists may be an effective tool against mass media bombardment. "Thereʼs an enormous difference between imitation and appropriation," says Rene Morales, a curator at the Miami Art Museum, which co-produced an installation by Fairey in December 2009. "Appropriation is a creative act; itʼs become one of the most effective ways to make art in a media-saturated word."13

The Pop Art of Rauschenberg, Warhol, Prince, and others influenced Fairey. "My favorite artists are people like Jamie Reid and Rauschenberg and Warhol, who incorporated existing art work in their work but did it in a way that made something that wasnʼt very special incredibly special," he says.

To those who decry lack of originality in Faireyʼs work, the artist agrees. "The idea of originality is pretty ridiculous. Itʼs virtually impossible to be original. Language is based on reference. To me as a visual artist, I use reference in my work all the time, both images that have a specific

connotation and styles that have a specific connotation."

For instance, in the Andre artworks, Fairey wrote "Obey" in red capital letters. This was his homage to ʻ90s art star Barbara Kruger, whom he calls "the most political, outspoken artist" of that time. "I liked her work and I thought that if I used that style, people were going to wonder what I was trying to say. I think she understood she should be flattered."

Russian Constructivism, Reid, Warhol, Kruger: The influences on Faireyʼs work are clear. The artist is as unapologetically derivative in his image choices as in his styles. He doesnʼt draw or paint the central figures of his pieces. He uses images created by others, either by photographers with whom he is collaborating, or images he finds online, or at agencies that sell stock photos, or that are already well known (such as his series on famous musicians). "Thereʼs no shortage of images," he says with a twinkle of ironic mischief. "Itʼs just that thereʼs an abundance of lawyers as well."

Prince simply rephotographed some of his most famous images, without modification. Fairey alters, sometimes radically, the works he appropriates, with exacto knives, computer tools, or by hand illustrating them. He defends his methods philosophically.

"Iʼm biased to my own idea that images are abundant but making them special is whatʼs important. Looking at how to distill what will make something iconic is what I think my skill is. Thereʼs some people who have great brush strokes and others who come up with cool color combinations. This is my skill, and whether the law says itʼs okay or not, itʼs what my skill is. ...

"Thereʼs a huge debate with new technology about what constitutes legitimate art. Does it have to be done with a paintbrush or with your hands? I enjoy illustrating with my hands. But really, your eyes make the art. You make the decisions by looking at things and transferring what you want to do in any number of ways, whether itʼs with your hands or digitally or with photography. The end result is whatʼs important. You may be Jeff Koons and have fabricators build it and never touch it. That to me is whatʼs art about: Whether that end result, however you got there, affects people and says what you wanted to say."

Sampling and Appropriation

Digital technology is radically changing the way the arts are made, transmitted, communicated, marketed, taught, learned, and controlled. Nowhere is this clearer than in the development of remixing and sampling. The ability to duplicate audio clips with commercially available technology became the basis for two important musical forms born in the 1970s: Jamaican dub and its descendent, hip-hop. In a Kingston recording studio, engineer King Tubby took preexisting musical tracks brought in by the artists and producers who had recorded them and cut and pasted, electronically tweaking along the way. "The salient point about Tubby is not that he invented the remix (although he did). Itʼs that the concept of the remix reinvented modern music," writes musical historian Greg Milner.14

A few years later in the Bronx, such DJs as Grandmaster Flash and Koolmaster Herc plugged their sound systems into lampposts and performed for block parties. MCs rapped over instrumental tracks; thus hip-hop was born. DJ/producers mixed hooks and beats from multiple records, obscure or famous, to create whole new songs -- the audio counterpart to Rauschenbergʼs combines, or Reidʼs and Faireyʼs collages. The commercial development of cheap samplers made what had been the high-art form of appropriation easy and ubiquitous. It also fueled the most important creative outpouring of music of the last 30 years, as rap artists emerged from ghettos, barrios, suburbs and small towns around the world. Hip-hop is an example of the environment of creativity that law professors James Boyle and Lawrence Lessig both argue is the core context of intellectual property law.15

The art of cutting, pasting, and remixing -- whether in word-processing software, Photoshop, iMovie, wherever -- is now intrinsic to computer culture. Lessig and many others see this as part of the radically transformative power of digital culture. "For the Internet has unleashed an extraordinary possibility for many to participate in the process of building and cultivating a culture that reaches far beyond local boundaries," Lessig writes. "That power has changed the marketplace for making and cultivating culture generally, and that change in turn threatens established content industries."16

Since 2006 the MacArthur Foundation has been funding a $50 million study of digital culture and learning. In a 2006 white paper written under funding from that study, Jenkins et al identify the skills that are enabled by new media and explore how they might be implemented in classrooms. The paper identifies appropriation as one of these main skills. "The digital remixing of media content makes visible the degree to which all cultural expression builds on what has come before," Jenkins et al write. "Appropriation is understood here as a process by which students learn by taking culture apart and putting it back together."17

Faireyʼs "Hope" poster is a definitive example of appropriation, as launched by his artistic and musical predecessors (Fairey also spins records under the name DJ Diabetic) and described by the white paper. "Appropriation enters education when learners are encouraged to dissect, transform, sample, or remix existing cultural materials," Jenkins et al wrote.18 Fairey was engaged in the essential appropriative processes of analysis and commentary when he remixed Garciaʼs photo.

The Clampdown

" Appropriation may be recognized and respected by artists, punks, rappers, scholars, and educational foundations. But it has become the center of a legal battleground. As an artist being sued for copyright infringement, Fairey follows in the footsteps of Richard Prince and rappers 2 Live Crew. But he is the first creative person to be engaged in litigation with a news giant during a time when internet communication technologies have fundamentally unsettled media organizations (or what I like to call the mediacracy).

IP law is complicated, to say the least. As Jessica Litman quips, "Copyright law questions can make delightful cocktail-party small talk, but copyright law answers tend to make eyes glaze over everywhere."19 Essentially, the law in America historically seeks a balance between the need to guarantee creators and inventors a financial incentive to create and invent, and the right of the public at large to participate in the free exchange of ideas. The overall goal, as stated in the Constitution, is "to promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts."

!ntrinsic to that progress and free expression, certain uses of copyrighted material are protected as fair use. "The Copyright Act allows the copying of copyrighted material if it is done for a salutary purpose -- news reporting, teaching, criticism are examples -- and if other statutory factors weigh in its favor," writes legal scholar Paul Goldstein.20

The Miami bass group 2 Live Crew took their fight for the right to appropriate all the way to the Supreme Court. In 1990 music publishers Acuff-Rose sued the salacious rappers for sampling the Roy Orbison song "Oh, Pretty Woman," to which they owed the rights. 2 Live Crewʼs lawyers defended the use as an act of parody and therefore an example of fair use. The Supreme Court agreed. "The goal of copyright, to promote science and the arts, is generally furthered by the creation of transformative works," Justice David Souter wrote, in a decision that has ramifications for Fairey.21

But other acts who have used samples have not been able to claim the parody fair use defense and lost their cases. Since the rapper Biz Markie was forced to remove a track from his 1991 album I Need a Haircut, musicians have repeatedly been sued over royalties. Now record companies are paranoid about any and all use of samples. What some artists and critics have called the genreʼs current demise could be in part related to the legal crackdown on sampling.22

Indeed, there is something about the digitization of pop music that has caused jurists and legislators to side with multimedia corporations in a clampdown on copying that is changing the rules of intellectual property. The courts shut down music distribution systems Napster and MP3.com and issued restrictive, expensive licensing rules that effectively silenced Internet radio for a time. Lessig, the founders of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, and others have documented and argued against this erosion of free culture. "In the middle of the chaos that the Internet has created, an extraordinary land grab is occurring," Lessig writes. "The law and technology are being shifted to give content holders a kind of control over our culture that they have never had before. And in this extremism, many an opportunity for new innovation and new creativity will be lost."23

Litman refers to this land grab by the vested interests of media conglomerates as the Copyright Wars. "If current trends continue unabated, however, we are likely to experience a violent collision between our expectations of freedom of expression and the enhanced copyright law," she writes.24

******************************(MORE TO COME)*******************************************************

Evelyn McDonnell is doing life backwards: After more than two decades of writing about popular culture and society, she's getting her Master's in arts journalism as an Annenberg Fellow at the University of Southern California. She is the author of three books: Mamarama: A Memoir of Sex, Kids and Rock 'n' Roll; Army of She: Icelandic, Iconoclastic, Irrepressible Bjork; and Rent by Jonathan Larson. She coedited the anthologies Rock She Wrote: Women Write About Rock, Pop and Rap and Stars Don't Stand Still in the Sky: Music and Myth. She has been the editorial director of www.MOLI.com, pop culture writer at The Miami Herald, senior editor at The Village Voice, and associate editor at SF Weekly. Her writing has appeared in numerous publications and anthologies, including Rolling Stone, The New York Times, Spin, Travel & Leisure, Interview, and the LA Times. She codirected the conference Stars Don't Stand Still in the Sky: Music and Myth at the Dia Center for the Arts in New York in 1998. She has won several fellowships and awards. "Nevermind the Bollocks" is part of a larger project Evelyn is researching on artists in the age of content. You can contact Evelyn at evelyn@evelynmcdonnell.com.

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=7b7b43e7-c1a2-4001-bada-efc82508d276)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=f40d85f8-ffe1-4796-a8e1-d4565f636ac1)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=3a2cd20d-c2e4-4294-aa7e-9f5b6edf96d9)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=5991de4b-9093-40d1-8312-7ba5dd59b045)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=0a7858cb-61f2-400a-9e74-32b6a8eea84e)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=ffbee125-80c5-4d0d-8a51-3bd6cd3b2514)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=7b7b43e7-c1a2-4001-bada-efc82508d276)