There's an emphasis throughout the book on user-generated content. One can argue that modding and other user-generated forms of content have made it easier for women to repurpose existing games to better meet their interests. Yet, one could also argue that this reliance on user-based solutions has marginalized female-interests into narrow niches rather than reshaping the design of commercial games. What do you see the gains and losses surrounding user-generated content?

CARRIE: I applaud tools to place modding and customization in the hands of more players. But these new tools will not stop advocates for girls to grow their technological comfort and expertise from wanting them to pursue the more difficult (and more powerful) advanced forms of customization through programming. Hopefully even when in-game toolsets for customization are available, it will still be possible to dig deeper and change the game even more.

JILL: The chapter I wrote with Shannon Campe describes the types of games made by 126 middle school girls, when they are given the tools and supports to design and program their own games. In fact, we found that girls' games were not highly gendered. Instead, many used humor to play with, explore, and challenge gender stereotypes. At the same time, they created games that addressed topics of great interest to them, such as fears about getting into trouble at home or school, and on moral decisions. These are topics that are relevant to many teens (male and female) but are completely absent from the most widely accessible games.

YASMIN: It's one of these unpredictable and interesting twists in the history of gaming that for once researchers interested in gender and games predated a paradigm shift in what you now call participatory culture. User-generated content carries with it the high and low: most of what is generated is not particularly compelling, if only for personal reasons, but then there are always a few examples that rise to the top. It's a gain because so many interesting developments are happening on the margins of gaming in discussion boards, machinima - this is what makes gaming an interesting experience. It's a loss if we see player-generated content as the answer to the gender issue. It's not. There is a place for professional design and production and consequently the people there need to become more cognizant about how inclusive or exclusive certain design decisions are.

All evidence suggests that adult women constitute the largest market for casual games. Has this market dominance led to any shifts in the decisions made by game designers serving this space? Does the book offer any insights into why more women play casual games than platform games?

CARRIE: Adult women tend to have less free time and the free time they have is available in shorter chunks of time. That makes games they can pick up and play in short blocks of time more possible and more appealing. Some casual games are available on platforms, but purchasing the console and getting it out and setting it up can be more than a casual commitment. Using the PC for games and the rest of life is in line with multitasking games and the rest of life.

Casual game companies are adopting approaches to acquire a sophisticated understanding of their market. Part of the beauty of online games is an ongoing connection with the player and continuous collection of play data. The game companies I am familiar with involve their most avid players and other volunteers as beta testers, and prior to beta, conduct frequent play tests before deciding the next game is ready to shift. Once a game company has a successful property, they start working with that audience to expand and improve. I don't see the market and the game company as being totally separate. Game design is becoming quite an intimate dialog.

YASMIN: This is really one of the areas deserving more attention research-wise; it just popped up when we started pulling together the book edition. To begin with the name alone 'casual' is of course a misnomer. It implies that these games are not as hardcore or serious as platform games because they don't require hundreds of hours of game play. Some however argue if you compile all the hours spend on casual games albeit distributed you end up with similar levels of involvement.

TL Taylor also made the observation that many of these word and puzzle formats found among casual games have a longstanding history of women playing them. So what we see is not the sudden emergence of the women gamer or a new genre but rather a continuation of traditional game play moving onto a new platform. It might be worthwhile to untangle all these different aspects ...

When we first edited our book, we were often asked why it mattered whether or not women played games. A decade later, what evidence has emerged which might offer a better response to this question?

CARRIE: I think games are still in the process of oozing into all walks of life. So the "one decade later" mark is not an end point but a stepping stone. There will be more change in the next ten years than there were in the last ten years. Games are sometimes and will increasingly be necessary for some jobs, and recommended for personal physical, emotional, and cognitive health. The Pew Foundation report on teens, gaming, and civic life reported that 99% of teens play games, and those who play more were more likely to be active in civic life.

I admit I am a blatant enthusiast, but games offer the curious mind a way to experience, learn, and play outside of the mundane constraints of the physical world. They are important for socialization and for maintaining and performing interpersonal relationships. They are part of participating in modern culture. Also, as games for health, games for learning, and games for social change continue to grow, playing games will be increasingly necessary.

JILL: The chapter by Elisabeth Hayes directly addresses this question. There has been a steady decline in student enrollment and graduation from computing majors in college, and a corresponding decline in the US IT workforce. Hayes argues that gaming can build IT expertise, which may potentially help to fill this gap.

YASMIN: There is one particular reason why it matters now more so than 10 years ago whether or not women and girls play games. This reason is tied to the current interest in games as promising learning and teaching tools. If we consider games effective tools and bring them into schools for that reason, then we better pay attention to their design so that everyone can learn with them. Then of course it matters what outside of school experiences you have because there is ample evidence that this impacts students' participation and success in the classroom.

The book offers some close consideration of the experiences of women working in the games industry. What factors might make this industry more challenging for women than for men to enter and maintain careers?

CARRIE: The huge barrier is programming. 95% of game programmers are male, and the proportion of females major in Computer science continues to decline. For the most part, those with a major voice in game design are the programmers and artists (also 85% male) who work on the game day after day. We either need to find ways to get more girls and young women interested in computer science, or else game development culture needs to open up roles for design consultants who don't come from the ranks of programmers and artists, but contribute in other ways.

JILL: The chapters by Mia Consalvo, and by Tracy Fullerton and her colleagues, describe how the culture of the gaming industry prevents women from entering and staying. Factors include crunch times that force employees to choose between home and work life for extended periods of time, and a devaluing of games that have social value.

The growing emphasis upon "serious games" and educational games raises new questions about gender, since it would be a tragedy if the use of games in the classroom made it that much harder for girls to learn and embrace Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math related subjects. What should educational game designers learn from the research presented in your book?

CARRIE: Part 4 of the book (changing girls, changing games) includes 3 chapters about science, math, engineering, and technology (SMET) games designed specifically for girls. The Click Urban Adventure is a mixed reality detective game in which teams of girls work together using science to solve a mystery. Kristin Hughes at Carnegie Mellon University used extensive formative research to understand some of the needs and desires of urban middle school girls in Pittsburgh. She was able to match narrative types, science tasks, tools and technologies, characters and personas to create a game very well suited to her audience. Her research showed the game was successful in generating a sense of agency and interest in SMET. Thus, games for learning do not, necessarily, exclude girls.

Caitlin Kelleher developed storytelling Alice, a tool for constructing animated stories, and for learning programming along the way. Her hunch that girls would be more interested in programming in order to build a story rather than programming to create a rudimentary game proved to be right on target. Middle school girls who used the Storytelling version of the ALICE programming software instead of the generic version learned more programming, were more delighted with the end product, and were more interested in going on to study programming.

Mary Flanagan created Rapunzel, a game in which players cooperate and compete to program dance moves. She and her team struggled to embed key activist social values within gameplay, such as sharing, cooperation, diversity, autonomy, self-esteem, and authorship.

Taken together these three projects shows that educational games certainly can be designed to appeal to girls. They reinforce the appeal of story and character and remind that games embody values whether designers intend them to or not.

The Heeter and Winn chapter reports on an experiment in which we found that rewarding speedy play interfered with girls' learning, whereas rewarding exploration slowed boys down and helped their learning but did not change girls play behavior positively or negatively. So the chapter does advise educational game designers to come up with ways to make a game "fun" other than including a time limit. As we teach in serious game design graduate classes, creating serious games is even harder than creating games. The audience is often forced to play and usually includes males and females. Learning outcomes, not just fun, must be considered. I am convinced we are all still learning how to make great games for learning. Making the experience good for all learners is part of the requirement.

A decade ago, the core question was whether we should design games specifically for girls or so-called "gender neutral" games to be played by boys and girls together. Is this still a burning question? If so, what new perspectives have emerged over the past decade?

CARRIE: That question makes me schizophrenic. In the collection of research citations on gender and gaming that I have been curating, the two most frequent tags are "gender stereotypes" and "what women want." The gender stereotype research tends to complain about girls and women are portrayed or conceptualized in stereotypical ways that ignore the wide diversity of female-ness. The what-do-women-want research reveals gendered desires and offers suggestions about how to create games to appeal to females.

From a design research perspective, Alan Cooper's proposition to "design for just one user" follows the tradition of designing products to "delight the few, please the many." That perspective implies that very best games for me would be designed for me. Some of what delights me also delights most humans. Some of what delights me would only appeal to a handful of other telecommuting, cat loving 52 year old new media professors. Even just satisfying one player would require many different Carrie-games, not just one. Each of us is more than our gender. The call for "games for girls" is a gross generalization. And yet, of course, some game designs are likely to be more appealing, overall, on average, to females and others to males. Schizophrenic. Sorry.

In her chapter, "Are Boy Games Even Necessary?", Nicole Lazzaro points out that designing for an extreme demographic reduces market size. An extreme male-typed game or an extreme female-typed game both leave out what players like most in most games. Games have changed enormously in the last decade, transitioning to become a mainstream medium and big business. With such an enlarged playing field, the answer from a business perspective is yes games for girls and games for boys and games for everyone. Gaming is large enough that it is beginning to resemble the magazine market. There can be very narrow market game franchises (paralleling the range of women's interest magazines from Vogue to Ms.) and more mainstream game franchises (paralleling Time or Newsweek).

Gender and gaming researchers tend to be more interested in empowering girls and women to engage with technology than they are with increasing game industry revenues. Betty Hayes' chapter points out that boys are more likely to engage in constructive, game-related activities such as modding, machinima, and creating fan web sites. These behaviors contribute to their IT expertise. Games for girls often do not include modding or recording, and therefore inhibit rather than facilitate tech expertise. Tracy Fullerton, Janine Fron, Celia Pearce, and Jackie Morie envision a "virtuous cycle" in which more women work in the game design industry, resulting in more games that appeal to girls, resulting in more girls becoming interested in becoming game designers. It doesn't matter whether the games are for girls, or gender neutral (ugh, that sounds so bland). We just want more appealing games.

My own research with colleagues Brian Magerko and Ben Medler at Georgia Tech and Brian and Jillian Winn at Michigan State University is moving in the direction of considering player type and motivation. We are working to develop and study adaptive games that express different game features depending upon what each individual player enjoys the most. Thus, instead of creating a game for girls, or a game for everyone, we create a game that can transform to become better for each individual player.

YASMIN: Can a game, or anything else for that matter, ever be 'gender-neutral'? And who decides? Game design can and should be more inclusive; one doesn't need to disrupt the narrative to offer more options for customization of characters or levels that are now common place for most games. That said, if we deal with younger players and school contexts, we need to be deliberate on what choices we offer in game designs to facilitate learning for various players.

In film studies, there has been extensive discussions of whether feminism has implications in terms of production processes and formal practices. Is there such a thing as a feminist approach to game design and if so, what would it look like?

YASMIN: A book chapter by Mary Flanagan and Helen Nissenbaum suggests an approach on how designers can identify the values that impact their design decisions from the initial conceptions to prototyping and play testing. You can call this a feminist design approach, if you want, or just plain good design strategy that can help everyone design better games.

We pointed to the rise of game companies as sites of female entrepreneurship as one factor that might shift the gender content of games. Why do we still see so few games companies run by women?

CARRIE

: It seems like that ought to have started to change by now. Soon, perhaps? A few years ago game industry professionals complained that innovation was stifled because the game industry giants controlled distribution channels. But the growth on online computer game and movement to open up access to consoles seem to have eased some of the roadblocks.

Also, the proportion of female programmers in the game industry was only 5% in 2005, and 13% artists. The industry retains an ethic of "you have to be there when decisions are made" and an expectation that only those who do the heavy lifting have earned a say at the game design table. I am hopeful that new roles will open up such as design consultant to permit much broader participation in game design.

Happily, the Serious Game Design MA program at my university has had close to 50-50 female/male ratio of students in the first two years we've offered it. From where I sit (in a San Francisco basement telecommuting to a Midwestern university), there is plenty of interest on the part of women, and some are intending to start companies. Hopefully this same experience is happening on a much wider scale.

Our book ended with a consideration of Female Gamers as offering an alternative perspective on the "girl's game movement." Your book includes an interview with Morgan Romine from Frag Dolls. Such groups continue to be highly controversial with both feminist supporters and detractors. How would you evaluate their contribution to the issues this book explores?

CARRIE: A writer at the Chicago Tribune called to interview me about the release of the last Lara Croft game, hoping, I think, that I would be outraged. My response was to say Angelina Jolie is really cool, and although Lara's dimensions are ridiculous I am enormously glad to have a strong albeit ridiculous female character be the basis of a game franchise. I've had fun discussion with some of my male undergrad students in a gender and games special topics course, talking about what it feels like to them to play her.

But you asked about Frag Dolls. My response is similar. I celebrate every game conference attendee they beat (male or female). What a nice counter-stereotypical impression they walk away with. I hate the violence of video games and it bothers me that anyone enjoys blowing people and things up, even in a game. I love their confidence and their energy. They are being exploited, but they are also getting paid to do something they really enjoy. It is the birthright of Frag Dolls and other young women to contradict interpret and express the next generation of feminism.

YASMIN: The Frag Dolls are also opening a whole new chapter on the professionalization of gaming that is happening in the US; it has been around in Asia for quite some time. TL Taylor, one of our book contributors, actually examines in her chapter the ramifications of this change in the gaming landscape. A group like the Frag Dolls is just the most visible signpost of this change. As gaming moves into mainstream entertainment and professions, it can and will not escape the gender issues present in other industries as well. Ten years ago, the observations in From Barbie to Mortal Kombat seemed to focus on a group on the margins of technology while in fact, they were telltale signs of things to come. The chapters in Beyond Barbie and Mortal Kombat discuss the complex and continuing story of women and technology now situated in the context of gaming.

A Professor of Learning Sciences at the University of Pennsylvania's Graduate School

at Education, Yasmin Kafai leads research teams investigating learning opportunities in

virtual worlds, designing media-rich programming tools and communities together with

colleagues from MIT, USC and industry. In the early 90's at the Media Lab she was one

of the first researchers to engage hundred of children as game designers in schools to

learn about programming, mathematics and science. While at UCLA, she launched virtual epidemics in Whyville.net, a massive online world with millions of players age 8-16, to help teens learn about infectious disease. She also studied how urban youth create media art, games, and graphics in Scratch, a visual programming language developed together with MIT colleagues. Her research has been published in several books, among them Minds in Play" (1995), Constructionism in Practice (1996 edited with Mitchel Resnick), and the upcoming The Computer Clubhouse: Constructionism and Creativity in Youth Communities (edited with Kylie Peppler and Robbin Chapman). She has studied in France, Germany and the United States and holds a doctorate from Harvard University.

Carrie Heeter is a professor of serious game design in the department of Telecommunication, Information Studies, and Media at Michigan State University. She is co-editor of Beyond Barbie and Mortal Kombat: New Perspectives in Gender, Gaming, and Computing and creator of Investigaming.com, an online gateway to research about gender and gaming. Heeter's innovative software designs have won more than 50 awards, including Discover Magazine's Software Innovation of the Year. She has directed software development for 32 projects. Her research looks at the experience and design of meaningful play. Current work includes design of learning and brain games which adapt to fit player mindset and motivation and persuasive games where the designer goal is to engender more informed decision-making on complex socio-scientific issues. Heeter also serves as creative director for MSU Virtual University Design and Technology. For the last 12 years she has lived in San Francisco and telecommuted to MSU.

Jill Denner is a Senior Research Associate at Education, Training, Research Associates, a non-profit organization in California. She earned her Ph.D. in Developmental Psychology in 1995 from Teachers College, Columbia University. She studies gender equity in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics, with a focus on Latinas, in partnership with youth, schools, and community-based organizations. She edited the book Latina Girls: Voices of Adolescent Strength in the US (2006, NYU Press) and is the founder of Girls Creating Games where she conducts research on learning and technology in the context of after school programs.

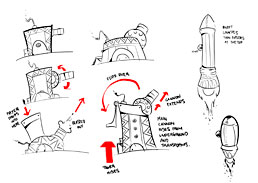

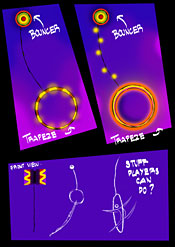

This summer, 45 Singaporean students, drawn from many of the island nation's universities, colleges, polytechs, and art schools, came to MIT to work with students from Comparative Media Studies and Computer Science through the MIT-Singapore GAMBIT games lab. The lab, funded by the National Research Foundation and the Media Development Authority, functions both as a training program fostering new talent and as a incubator for new approaches to game design, both of which will help recharge games as a creative industry in Singapore and, we hope, inform discussions of games as a medium around the world. It does so by putting Singapore and MIT students on teams which work together all summer to develop playable games which we hope will stretch our understanding of the medium. Having attended the roll out of this summer's games and having recently seen the Singapore students demoing what they created at a Pan-Asian games industry gathering in their home country, I have to say I am tremendously excited at what the GAMBIT teams have been able to achieve.

You can

This summer, 45 Singaporean students, drawn from many of the island nation's universities, colleges, polytechs, and art schools, came to MIT to work with students from Comparative Media Studies and Computer Science through the MIT-Singapore GAMBIT games lab. The lab, funded by the National Research Foundation and the Media Development Authority, functions both as a training program fostering new talent and as a incubator for new approaches to game design, both of which will help recharge games as a creative industry in Singapore and, we hope, inform discussions of games as a medium around the world. It does so by putting Singapore and MIT students on teams which work together all summer to develop playable games which we hope will stretch our understanding of the medium. Having attended the roll out of this summer's games and having recently seen the Singapore students demoing what they created at a Pan-Asian games industry gathering in their home country, I have to say I am tremendously excited at what the GAMBIT teams have been able to achieve.

You can