In Search of Indian Comics (Part Three): I Mean, Really, Where Are They?

/This is the third part of a series about my adventures in Delhi, which were largely structured around my efforts to learn more about comics publishing in India. Here's a bit more about my lunch with the comic artists at the Delhi Craft Museum, drawn from my travel diary:

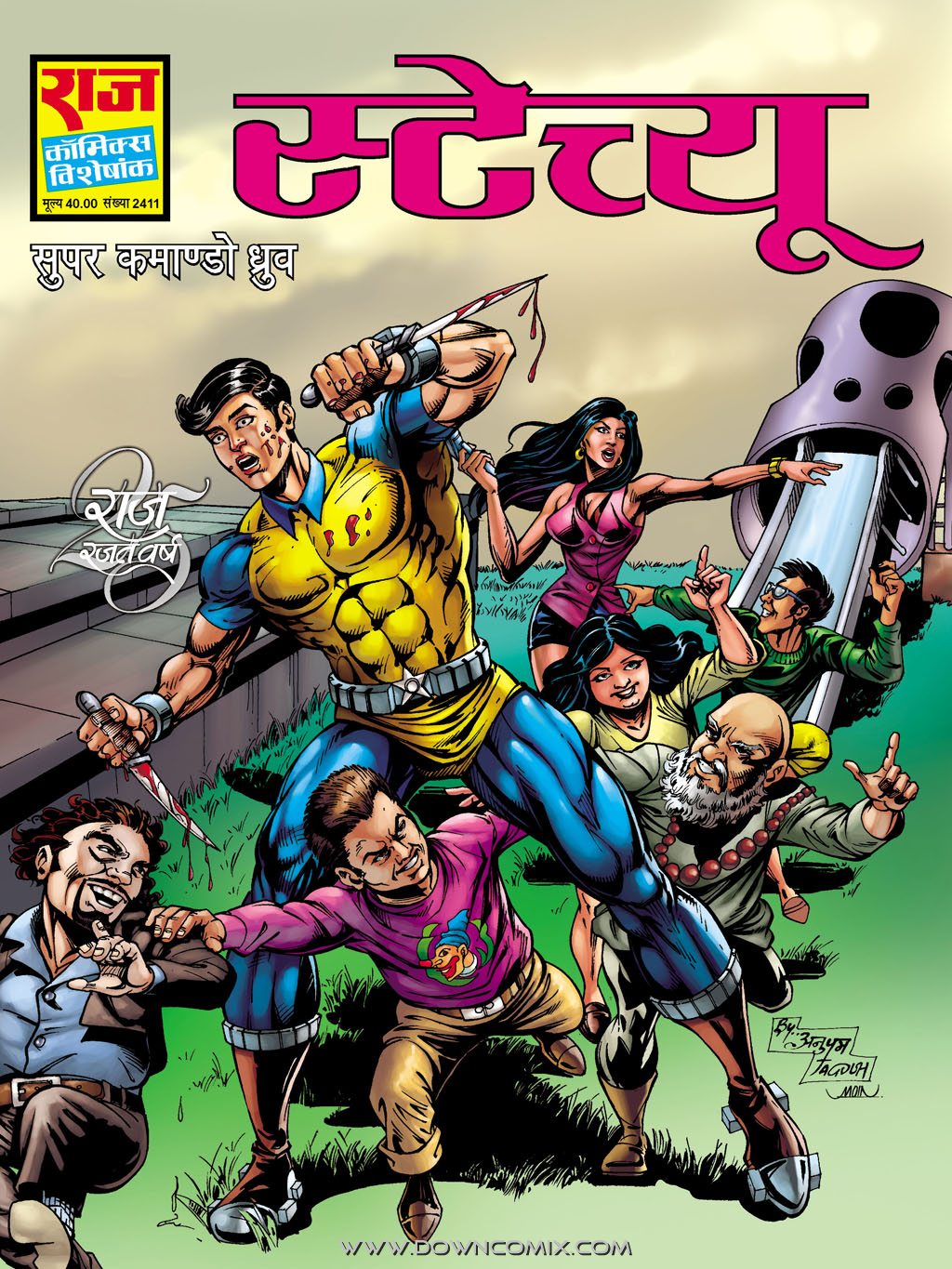

"There are NO comic stores here. Comics are available through multiple other channels depending on what kind of cultural production we are discussing. So, there are comics in many of the regional languages which even people in other parts of India do not know exist. Amongst English comics, there are pop or low brow titles (such as the locally produced Raj comics which have the most sustained history of adventure comics in the country) which are sold only through news-stands.

On the other end of the scale, there are the ACK comics – essentially the Indian version of Classics Illustrated, mythological tales or stories of national heroes; these are sold mostly through the children’s section of bookstores. Unfortunately, most of the graphic novels with more mature content (not sexual, never sexual, but, as we saw last time, often highly political content) are also most often sold through the children’s book section at bookshops, because there is still a perception that comics are aimed exclusively at children, even when they are not. There are certain bookstores whose managers get graphic novels and treat them appropriately – they gave me the names of several – but these are few and far between and the most reliable place to buy comics would be through online bookstores such as Amazon or its India-based rival Flipkart. The creation of graphic novels in India, accordingly, moves in fits and starts.

One of the folks at lunch – Orijit Sen – published River of Stories which is credited as the first graphic novel to come out of India (now out of print). There have been a smattering published since, mostly by traditional book publishers, especially those which deal with art books. None of the folks I met live off of their work on comics per se, each works in other corners of the graphic arts world, including doing advertising work or commissioned art pieces. They are seeing shifts in the cultural status of comics, though, as parents and educators have come to accept that “at least the kids are reading” and that these visual forms may be effective at reaching those who the system might otherwise leave behind. Sen talked about being commissioned by a textbook company to create graphic stories about the history of India that would be part of the textbooks; he jokes that it was the same publisher that produced the textbooks he used to hide his comics within when he read in class as a child.

And then there is a new wave of comics being produced for the web, and so they were especially interested in the web comics movement in the west and intrigued by the role Kickstarter now plays in crowd-funding the production of independent comics here. They seem to be familiar with many U.S. based artists – Aparajita told me that she learned to draw as a child by copying pictures from Mad magazine (and we both wax nostalgically about the glory days of Mad). I am invited to come to their studios for more conversation and so they can show me more of their work, an invitation I have accepted for Monday."

What follows are some segments from my travel notes for that following Monday, a day spent somewhat fruitlessly trying to track down contemporary graphic novels via local bookstores, following the suggestions we had received.

I had met Vartikka Kaul, a PhD student doing work on Indian superheroes, after a talk I gave at Jawaharial Nehru University a few days before. Vartikka grew up in Kashmir, an area which is on the border between Pakistan and India, and has been contested space, basically a war zone, for decades, and her ancestors come from Central Asia. Here's a picture of Kaul and myself exploring Hamayun’s Tomb.

Her project straddles film and print versions of these characters, though she says that nothing like a franchise system has emerged here. I am reminded of the curious history of the export of American comics in this region: how American superhero comics were slow to be imported but that some U.S. comic strips, such as The Phantom and Mandrake the Magician, which have long fallen from view in their home country, continue to be published and avidly consumed in India and across Asia. These stories offer some of the core building blocks of the superhero tradition, but most of the DC and Marvel characters only became visible here through film and television, belatedly creating a market for the comics themselves. I was amused that during my stage in Delhi the local paper showcased a cosplay party on the Society page, where various local celebrities came dressed as American superheroes.

With the exception of Raj, Indian publishers of pulp comics are short-lived, so few characters have developed much continuity or history, and the films have tended to be one-offs, at best with a sequel, often star vehicles for particular performers and thus the superhero becomes an extension of their larger star persona (in an industry which still has a star system much like Hollywood in the 1930-40s). She is interested though in shifts between mythological origin stories and more scientific/rational explainations of the sort more typical of western superheroes (i.e. scientific experiments gone awry). She’s interested in the superhero as a focus for transmedia storytelling and to some degree, on the gender dynamics of male and female versions of the superhero.

We discuss the phenomenon of regional filmmakers who actively remake western superhero stories for their local markets, a theme beautifully explored by Superman of Megalon, a 2012 documentary by Faiza Ahmad Khan. Here, a young Muslim man and his friends put all of their money and creativity into making their own Superman epic, localized to respond to the tastes and experiences of the residents of his economic depressed area.

I had been told by Orijit Sen that People Tree may be the best place in Delhi to buy graphic novels. (I learn later that this is because Sen is the owner of this particular shop). It is a small little boutique where the entire front half is taken over by clothing, nick-knacks, and local crafts, while there’s a very small back room area dedicated to books.

When I ask the staff about Indian comics, they refer me to the children’s book section, though there was not much to be found. I did find two newspapers full of what are called here “grassroots comics,” that is, educators go to work with children in the villages or the slums, and help them to translate their experiences into comics. So, these are amateur comics, produced through charity organizations.

And then we continued on to Oxford Books, where we have lunch in the café (highlight was a sweet beverage flavored by almonds and pistachios) and then some more searching for graphic novels. Here, the selection is almost entirely international – they have all of the volumes of Osamu Tezuka's Buddha, and they have a large selection of French comics (Tin Tin and Astrix), far fewer American comics, and almost no Indian comics – I get a graphic novel version of a popular children’s cartoon series and a book by an Indian cartoonist designed to help visitors from the Indian diaspora make sense of the local culture (Indian by Choice).

We go to several other book shops – most of which are very narrow stores, where books are piled into floor-to-ceiling mounds, and only the proprietor can help you find anything. What they have in stock at any given moment is almost entirely random. No wonder online book dealers have had such a huge impact here, even despite the desire for cash-based transactions. This is not a very good culture for book lovers.

Ironically, these Connaught Place book dealers are the focus of one of India's most acclaimed graphic novels, Sarnath Banerjee's Corridor. Here's how the stores are depicted there -- more or less accurately.

The graphic novel's protagonist Jehangir Rangoonwalla is described on the book's cover as "enlightened dispenser of tea, wisdom, and second-hand books," and there are memorable panels of him groping around amongst the mounds of books and putting his hands on just the right title for the right customer. The graphic novel sprawls outward from his shop, developing glimpses into the lives of various book collectors and wisdom-seekers, who are trying to make meaning of contemporary life in Delhi through sexual discipline, obscure collectibles, Marxism, religious sects, and vegetarianism, among a range of other world views. Banerjee's subsequent books, The Barn Owl's Wonderous Capers and The Harappa Files show a consistent fascination with contemporary and historical print culture, and seem designed to introduce the graphic novel (in various permutations) into this same book culture. But, ironically, the dealers depicted in Corridor did not, on this particular day, know how to put their hands on any of Banerjee's books.

Vartikha tells me about a chain called Leaping Windows, with branches in Banglore and Mumbai, which is set up like the comics cafes in Tokyo. You pay an entry fee and then can come inside and read any of the comics they have on the shelves, as you sip your coffee. This store also home delivers comics – but again, on loan rather than for purchase. We’ve since learned that the shop has closed in Banglore and perhaps in Mumbai, so even this is endangered. Vartikha asks me about the comics specialty shops we have in the U.S., like she’s seen on The Big Bang Theory, as if this possibility was beyond imagination, and shares her dreams of making it to San Diego Comic Con some day.

So, here's the bottom line: India has a new generation of gifted graphic storytellers, who are doing comics that speak in direct and powerful ways to the country's politics, comics that experiment with new visual languages for comics, often drawn from the country's rich and diverse folk traditions. These artists are slowly but surely producing work that people should be paying attention to. But, you can't really find them in Indian bookstores when you go looking and they are not making their way into comics specialty shops in the United States. If you want to find India comics, you have to look online.

Next: Inside Orjit Sen's Studio