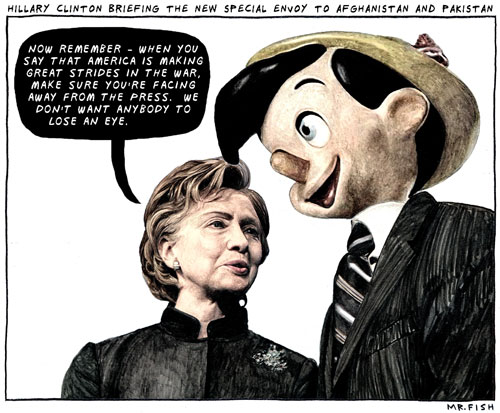

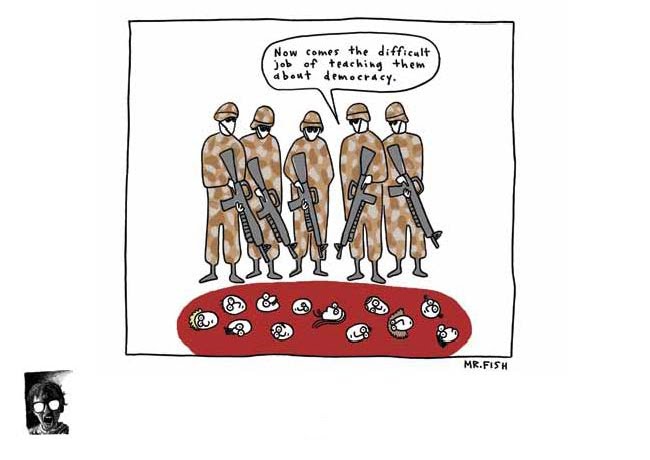

WARNING! Graphic Content: An Interview with Cartoonist Mr. Fish (Part Two)

/I was intrigued by your discussion of the classic definition of cartoons as “preparatory renderings.” This is often seen as an archaic or secondary meaning of the concept of the cartoon, but you seem to see it as more closely linked to the kinds of political and culture work cartoons perform. Explain. Yes, like I said in the book, the purpose of a cartoon, both as a preparatory drawing and as a finished piece of commentary published by a newspaper or a magazine, is never to embody perfection but rather to use imperfection to communicate possibility.

Specifically, a cartoon (both iterations of the word) is the beginning of a conversation on any given subject, not the final word, because it more reflects the deliberation over an emotion or an idea than it signifies a proselytizing conviction. To understand precisely what I’m describing, simply compare a propaganda poster that is designed to vilify an enemy or oversimplify a threat to humanity with a cartoon or a piece of fine art that is designed to challenge over-simplification and add complication to an issue so that it more accurately reflects the messiness and multiplicity of real life.

While your book’s title suggests an exploration of “political cartoons” and “comix”, there is much work here which would not fit a narrow definition of these terms, including photographs, sculptures, performance art, live action and animated video, and traditional paintings. What accounts for such a surprisingly expansive selection of materials?

True, the book was initially conceived as a scholarly examination of the past, present and future of editorial cartooning but very early in the process, when I was forced to define what an editorial cartoon was prior to making any assertions about its history or purpose, I realized that the definition of the word “editorial” was the exposition of a personal opinion and that “cartooning” was merely the rendering of that opinion in a pictorial form, or at least in a form that wasn’t entirely lingual or literary, a definition that encapsulated other forms of artistic expression such as photography, sculpture, performance art, etc.

Can you say a bit about your process in creating this book, especially what you think you gained by creating such a nonlinear and multimedia text, as compared to doing a printed book? What models did you draw upon in imagining what kind of work you wanted to create? There are places here where I found myself thinking about works as diverse as McLuhan's collaboration with Bucky Fuller, Peter Berger's Ways of Seeing, or Scott McCloud's Understanding Comics. But none of these have the affordances of digital media you drew upon.

It was always my intention to create a book that celebrated and examined art, not as a collection of precious historical artifacts or unique objects that require the context of chronology to have meaning or value, but as an actual living language that I would argue is the most precise and authentic form of communication yet devised by human beings.

Similarly, it was important for me to be able to present the material in such a way that reflected the diversity and expansiveness of art’s voluminous vocabulary, which meant that I needed it to move beyond the fixed confines of being just text and still images. (Reading sheet music is quite a different thing from listening to the sound of instruments being played.)

I also wanted the narrative of the book to reflect the unrestrained and scattered trajectory of every conversation I’ve ever had or overheard on the subject of both art and the meaning of life. To enter into a debate about Bauhaus design, for example, one should also be ready to talk about fascism, the Industrial Revolution, the Labor Movement, Expressionism, Haiku, the 1913 Armory Show, Phenomenology, Existentialism, Minimalism, IKEA, Marx, Upper Paleolithic stone carvings, 2001: A Space Odyssey and the very real difference between factualism and truth.

Both Marshall McLuhan and Berger’s Ways of Seeing were most definitely on my mind while writing this book, as was Wolfe’s The Painted Word, Mailer’s later collection, The Spooky Art and Donald Hall’s Life Work – so, too, was the work of Nietzsche, Fromm, Stephen Davies, Danto and others. In fact, I probably drew more on social philosophers and cultural critics than cartoonists and visual artists when trying to determine the function and significance of art.

Your book’s title, which warns about its graphic content, seems at first to be ironic but the deeper you get into this work, the clearer it is that you have set out to publish many of the most controversial images ever published -- in part as a celebration of the “uncensored artistic mind.” Were there images here which gave you pause or that presented challenges for your editors? How hard was it to produce a work that was as “uncensored” as this one seems to be?

None of the images contained in the book gave me pause, no. In fact, I just finished a unit on offensive art for a course that I’m teaching at the University of Pennsylvania where I assigned a paper that was designed to prove how the concept of obscenity is a socialized construct rather than an innate reaction to an external phenomenon. For the assignment I asked the students to search for a piece of art that was personally offensive to them and then they needed to defend its right to exist.

After the papers were turned in I asked them to tell me about the experience of searching for offensive art and they told me that the task was nearly impossible when they searched alone because nothing was truly offensive to them. Only when they looked for images with other people around did they feel shock or shame. The exercise was analogous to reading or writing or saying a dirty word while alone versus engaging with so-called obscene language while in a public space; the former inspiring no reaction whatsoever and the latter causing real and genuine discomfort, proving that obscenity, like patriotism, typically requires a herd mentality in order to be conjured.

I also explain to my students that it is in that private space, in that state of aloneness, wherein most artists conceive of their work, which is why some artwork can appear vulgar in its honesty or obscene beyond its intention when viewed in public. Bluntly put, you are more likely to pick your nose or scratch your ass without pause if you are alone than if you are in public and it is within that clarity of purpose and egoless satiation of a dilemma wherein an artist enunciates his or her undiluted utility most succinctly. (And that is why art as a language has greater potential to enlighten, because it operates with fewer restrictions and fearlessly accesses deeper troughs of knowledge with the blade of honesty than publically sanctioned methods.)

The only image from the book that presented any challenge to my editors was the photograph by Hans Bellmer of female genitalia titled I Am God. In fact, it was in danger of being removed unless I could somehow contextualize it within the narrative of my chapter about art that is difficult to look at. The solution, of course, was to add an author’s note that draw the parallel with Gustave Courbet’s famous 1866 painting of the same subject, which was titled The Origin of the World, thusly making the Bellmer piece legitimate by association.

Dwayne Booth has been a freelance writer and cartoonist for twenty-five years, publishing under both his real name and the pen name of Mr. Fish with many of the nation's most reputable and prestigious magazines, journals and newspapers. His work has appeared in Harper’s Magazine, the Los Angeles Times, the Village Voice, the LA Weekly, the Atlantic, The Nation, Vanity Fair, Mother Jones, the Advocate, Z Magazine, Slate.com, MSNBC.com and on Truthdig.com. In May 2008 he was presented with a first place award by the Los Angeles Press Club for editorial cartooning. In 2010 and 2011 he was awarded the Sigma Delta Chi Award for Editorial Cartooning from the Society of Professional Journalists. In 2012 he was awarded the Grambs Aronson Award for Cartooning with a Conscience. His most recent books are Go Fish: How to Win Contempt and Influence People, Akashic Books 2011, and WARNING! Graphic Content, Annenberg Press 2014. He is currently teaching at the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania.