Transmedia Education: the 7 Principles Revisited

/Last week, I participated in one of the ongoing series of webinars for teachers which is being conducted by our Project New Media Literacies team. The series emerges from an Early Adopters Network we are developing with educators in New Hampshire to drill down on the skills we identified in our white paper for the MacArthur Foundation and to think through how teachers in all school subjects and at all levels can draw on them to change how they support the learning of their students. Vanessa Vartabedian is the coordinator who has been running this series. Each month, they focus on a different skill. This month's focus was on Transmedia Navigation. The webinars are open to any and all participants and are drawing educators from all over the world. The webinars are also available after the fact via podcast. The Transmedia Navigation discussion involved not only some remarks by me but also a conversation with Clement Chau from Tufts University and Mark Warshaw from the Alchemists who has developed transmedia content for Smallville, Heroes, and Melrose Place, among other properties. "Our Ning site is where our community of educators are exchanging ideas and trying out resources. You simply need to sign-up and fill out a short profile to access the schedule of upcoming webinars, as well as links to the archived recordings for previous webinars."

The focus of transmedia navigation offered me a chance to think a bit more deeply about what it might mean for us to produce transmedia education and I thought I would share some of those insights with you.

Let's start with some first principles:

Transmedia needs to be understood as a shift in how culture gets produced and consumed, a different way of organizing the dispersal of media content across media platforms. We might understand this in terms of a distinction I make between multimedia and transmedia. Multimedia refers to the integration of multiple modes of expression within a single application. So, for example, an educational cd-rom a decade or so ago might combine text, photographs, sound files, and video files which are accessed through the same interface. Transmedia refers to the dispersal of those same elements across multiple media platforms. So, for example, the use of the web to extend or annotate television content is transmedia, while the iPad is fostering a return to interest in multimedia.

Multimedia and Transmedia assume very different roles for spectators/consumers/readers. In a multimedia application, all the readers needs to do is click a mouse and the content comes to them. In a transmedia presentation, students need to actively seek out content through a hunting and gathering process which leads them across multiple media platforms. Students have to decide whether what they find belongs to the same story and world as other elements. They have to weigh the reliability of information that emerges in different contexts. No two people will find the same content and so they end up needing to compare notes and pool knowledge with others. That's why our skill is transmedia navigation - the capacity to seek out, evaluate, and integrate information conveyed across multiple media.

The push for transmedia is bound up with the economic logic of media consolidation. Yet, there is a push to transform this economic imperative into an aesthetic opportunity. If entertainment experiences are going to play out across multiple platforms, why not use this principle to expand and enrich the experience which consumers have of stories? Why not see transmedia as an expanded platform through which storytellers can deploy their craft? As we think about transmedia in the classroom, there are several key justifications/motivations for integrating it into our learning and teaching practices.

First, as modes of human expression expand and diversify, then the language arts curriculum has to broaden to train students for these new forms of reading and writing. If many stories are going to become transmedia, then we need to talk with our students about what it means to read a transmedia story and as importantly what it means to conceive and write a transmedia story. This is closely related to what Gunther Kress talks about in terms of multimodality and multiliteracy. Kress argues that we need to teach students the affordances of different media through which we can communicate information and help them to foster the rhetorical skills they need to effectively convey what they want to say across those different platforms.

I've had good luck at getting students to think in these terms through assignments which ask them to propose ways of translating an established story into a new medium - for example, translating a novel or film into a computer game. This practice requires them to develop critical skills at identifying the distinctive features of specific stories and worlds and it requires them to think about the affordances and expectations surrounding other media. Check out my earlier blog post on this practice.

As educators, we need to model the effective use of different media platforms in the classroom, a practice which would support what Howard Gardner has told us about multi-intelligences. In this case, I am referring to the idea that different students learn better through different modes of communications and thus the lesson is most effective when conveyed through more than one mode of expression. We can reinforce through visuals or activities what we communicate through spoken words or written texts. Doing so effectively pushes us to think about how multiple platforms of communication might re-enforce what we do through our classrooms.

Some will object that this skill takes a mode of commercial production as a model for what takes place in the classroom. Didn't I note here just a few weeks ago the dangers of talking about "learning 2.0" because it confuses a business plan for a pedagogical approach. I think we need to be careful in this regard and if it were only Pokemon or Lost that operated according to transmedia principles, I might be much slower to advocate integrating these same principles into our teaching.

But here's the thing: Obi-Wan Kenobi is a transmedia character, so is Barrack Obama. In both cases, readers put together information about who this character is and what he stands for by assembling data that comes at us from a range of media platforms. In such a world, each student in our class will have had exposure to different bits of information because they will have consumed different media texts. As a result, one child's mental model of Obama may include the idea that he was not born in the United States, that he is a Moslem, that he is a socialist, or what have you, and we need some way of communicating across those mental models, we need a way of understanding where they came from, and we need to help students expand the range of media sources through which they search out and assess information about what's happening in the world around them. To some degree, teachers emphasis similar skills when they tell students to seek out multiple sources when they write a paper, yet often, they mean only multiple print sources and not sources from across an array of different media. All of this suggests to me that we need to make the process of transmedia navigation much more central to the ways we teach research methods through schools.

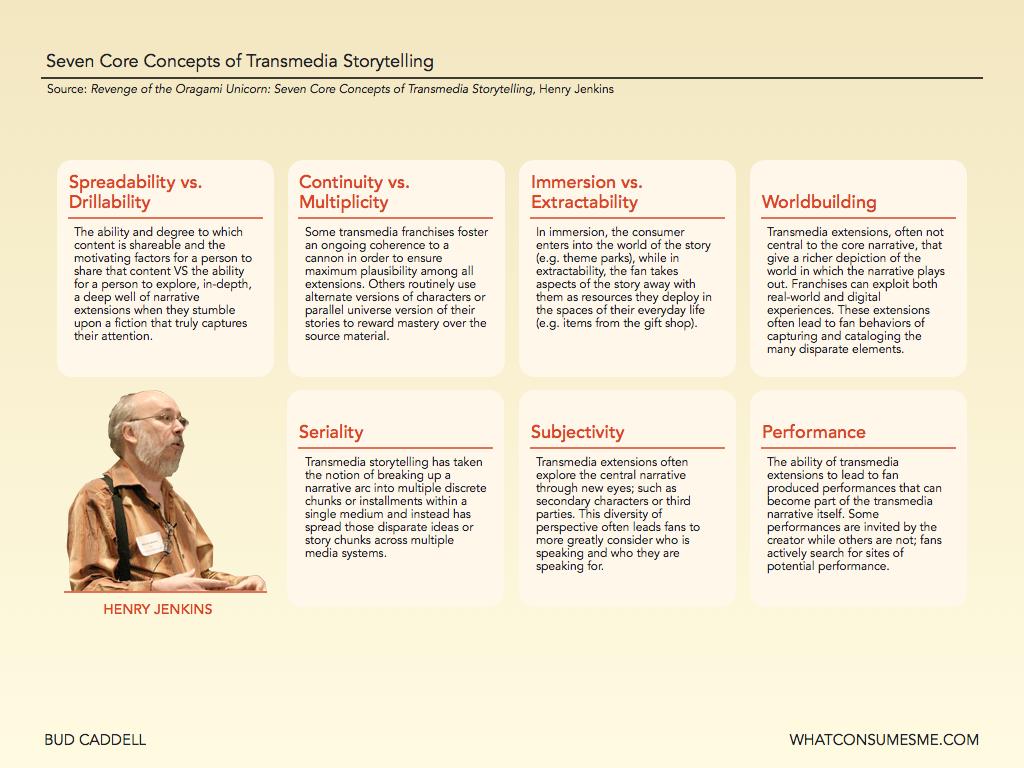

Vanessa asked me to share with the group the Seven Principles of Transmedia Entertianment which I presented through this blog last fall and suggest how they might relate to learning. I wanted to express some cautions about this exercise. Transmedia Storytelling is one of a range of transmedia logics, which might also include transmedia branding, transmedia performance, and transmedia learning. There is sure to be some overlap between these different transmedia logics, but also differences. I don't doubt that some principles carry over but we need to keep in mind that there may also be some core principles for transmedia teaching/learning which will not be explored if we simply try to adopt what we know about transmedia entertainment for this space. I hope that this blog can start a conversation which helps us to identify other principles which are specific to the learning domain.

Here goes.

Spreadability vs. Drillability Daniel Thomas Hickey wrote a series of posts (Part One, Part Two) which explore how the circulation of educational media might be described and improved by our model of spreadability. They are worth checking out.

But for the moment, let's think of this in a somewhat broader way. Spreadability refers to a process of dispersal - to scanning across the media landscape in search of meaningful bits of data. Drillability refers to the ability to dig deeper into something which interests us. A good educational practice, then, encompasses both, allowing students to search out information related to their interests across the broadest possible terrain, while also allowing students to drill deep into something which matters to them. This requires us as educators to think more about motivation - what motivates students to drill deeper - as well as class room management - how can we facilitate their capacity to dig into something that matters to them.

Continuity vs. Multiplicity The media industry often talks about continuity in terms of canons - that is, information which has been authorized, accepted as part of the definitive version of a particular story. Education has often dealt in the range of canon - not only the canon of western literature which deems some books as more worth reading than others but also the structures of disciplines and standards which determine what is worth knowing and how we should know it.

Multiplicity, by contrast, encourages us to think about multiple version - possible alternatives to the established canon. So, for example, Kurt Squire in his work on adapting Civilization III for the classroom talks about the value of asking students to think through "what if" scenarios about history - what if the Native Americans or Africans had resisted colonization, for example - that can be played out in the simulation game and which can help us to understand the contingencies of history. Asking what if questions both force us to think about the impact of historical events as well as the different factors which weighed in to make some possibilities more likely than others. As Squire notes, playing Civilization III encourages students to master the logic of history rather than simply what happened. The same thing happens when we explore how the same story has been told in different national contexts. It helps us to see the different values and norms of these cultures as we look at the way the story has been reworked for local audiences.

p>Immersion vs. Extraction In terms of immersion, we might think about the potential educational value of virtual worlds. I don't mean simply having classes in Second Life which look like virtual versions of the classes we would have in First Life except with far less human expressivity. I mean the idea of moving through a virtual environment which replicates key aspects of a historical or geographical environment. I am thinking about Sasha Barab's Quest Atlantis< or Chris Dede's River City as examples of fully elaborated virtual learning environment which rely on notions of immersion. I am also thinking about activities where students build their own virtual worlds - deciding what details need to be included, mapping their relationship to each other, guiding visitors through their worlds and explaining the significance of what they contain.

Extractability captures another principle which has long been part of education - the idea of meaningful props and artifacts in the classroom. In a sense, every time we have show and tell, everytime a student brings an element from their home culture into the classroom, every time a teacher brings back a mask or a tool from their visit to another country and displays it as part of their geography lesson.

World Building World Building comes out of thinking of the space of a story as a fictional geography. I've mentioned here before that L. Frank Baum described himself as the Royal Geographer of Oz. In this case, we do not simply mean physical geography though this is part of it. Books with a strong focus on worlds often include maps - whether it is the large scale map of Middle Earth in J.R.R. Tolkien or the much more local map of the rigigng of the ship found in many of Patrick O'Brian's books. Part of the pleasure of reading those books is mastering that fictional geography. But world building also depends on cultural geography - our sense of the peoples, their norms and rituals, their dress and speech, their everyday experiences, which is also often the pleasure of reading a fantasy or science fiction narrative. But it is also part of the pleasure of reading historical fiction and a teacher can use the activity of mapping and interpreting a fictional world as a way of opening up a historical period to their students. This moves us away from a history of generals and presidents towards social history as the key way through which schools help us to understand the past. And many traditional school activities encourage students to cook and eat meals, to make and wear costumes, to engage in various rituals, associated with other historical periods. If we develop ways of mapping these worlds as integrated systems, we can push beyond these local insights towards a fuller, richer understanding of past societies.

Seriality The media industry often discusses seriality in terms of the "mythology," which offers one way of understanding how we might connect this principle to traditional school content. At its heart, seriality has to do with the meaningful chunking and dispersal of story-related information. It is about breaking things down into chapters which are satisfying on their own terms but which motivate us to keep coming back for more. What constitutes the equivalent of the cliffhanger in the classroom? What represents the story arc which stitches a range of television episodes together? Or by contrast, what has to be present for a story or lesson to have a satisfying and meaningful shape even if it is part of a larger flow?

Subjectivity At heart, subjectivity refers to looking at the same events from multiple points of view. When we were going through my late mother's papers, we found a school assignment from the 1930s when she wrote the story of Little Red Riding Hood from the perspective of the wolf. When I mentioned this at the webinar, others mentioned Wicked which tells the Wizard of Oz from the vantage point of the Wicked Witch of the West. Matt Madden's book 99 Ways to Tell a Story: Excercises in Style is a great way to bring these issues into the art or language arts classroom: he tells the same simple story 99 times, each time tweaking different storytelling variables, including those around tense and perspective. In the history classroom, there's a value of flipping perspectives - how were the same events understood by the Greeks and the Persians, the RedCoats and the Yankees, the North and the South, and so forth, as a way of breaking out of historical biases and understanding what lay at the heart of these conflicts.

Performance In speaking about entertainment, I discuss performance in terms of a structure of cultural attractors and activators. The attractors draw the audience, the activators give them something to do. In the case of the classroom, there are a range of institutional factors which insure that you have a group of students sitting in front of you. But you still face the issue of motivation. When we were doing work on thinking about games to teach, we often had to ask the content experts to tell us what the information they saw as valuable allowed students to do. To turn the curriculum into a game, we had to move from information on the page to activities which put that information to use.

This is at the heart of any process-driven approach to learning. What are you asking your students to do with what you teach them? How are they able to adapt it in a timely and meaningful fashion from knowledge to skill? And tied to this is the idea of adaptation and improvisation, since in the entertainment world, different fans show their different understandings and interest in the entertainment content through very different kinds of performances. So, how do we create a space where every student can perform the content of the class in ways which are meaningful to them? In short, how might teachers learn to think about cultural activators in designing their lessons?