GLOBAL GENRES—Kaiju Connections: Disabled Ecologies, Visibility, the Posthuman, and Transnationality in Pacific Rim

/This contribution is part of a series of posts on genre and the ‘global shuffle’.

Kaiju as a genre has an established place in global cinema, tracing its origin from King Kong and Godzilla (1954), a popular Japanese franchise. Godzilla is inextricably tied to Japan’s national cinema, which reflects postwar trauma. It mirrors national and political anxieties with elements of myth and folklore. Over the years, kaiju movies have evolved beyond the realm of Japanese cinema, allowing countries to reinterpret the genre, which also mirrors their own national anxieties. Prominent Korean director Bong Joon Ho created The Host (2006), inspired by the McFarland incident and reminiscent of the 9/11 attacks, a resonance also seen in Matt Reeves’ Cloverfield (2008) (King, 2021). Jason Barr highlighted how Pacific Rim stands out from other kaiju films:

Pacific Rim, however, is somewhat out of the ordinary, and it may be because of del Toro’s affinity for old kaiju films. Otherwise, kaiju films of the 2000s and 2010s seem to eschew environmentalism and environmental emphasis in favor of a new brand of realism. Pacific Rim, therefore, in a variety of ways, can be considered an outlier to the trends of 21st-century kaiju films and more of a throwback to earlier eras. Few kaiju films in the Pacific Rim era of the 2010s mention pollution or environmentalism and instead focus more on international relationships and colonialism, which is a trend almost as old as the genre itself. (2016, p. 67)

Pacific Rim (2013) by Guillermo del Toro offers a unique take by veering away from traditional kaiju narratives. The discourse from national trauma shifts to global cooperation. The invasion of kaiju emerging from an alternate dimension represents an unprecedented global crisis. It demands collective action, requiring transnational cooperation and a solution that allegorizes a more universal problem, such as an ecological disaster like climate change. Pacific Rimpushes the nationalistic boundaries of monster films by highlighting the need for global solidarity in addressing shared threats that affect everyone. The kaiju genre maps a transnational evolution of “monsters” as a medium for expressing collective national traumas. Kaiju function as an effective metaphor that captures the devastations embodied within cultural conflicts, fears, and national traumas. In this essay, I draw on Sunaura Taylor’s (2024) concept of disabled ecologies to map out how it examines the invisible and visible “disabilities” embedded in human and non-human actors within the ecological system.

The kaiju genre is often used as a metaphor to signify destruction, but its presence also mirrors human nature. In this paper, I want to highlight how the monstrosity of kaiju can be understood as an ecological interdependence.

Disabled Ecologies: Invisibility and Visibility

When we encounter something out of the ordinary, our first instinct is to run, hide, and battle it to maintain familiarity. In almost every kaiju movie, the first encounter with the kaiju represents chaos and destruction. It displays humans’ first instinct: scream, run, and protect. Similar to how our body reacts to pathogens, it detects and builds a response to counterattack it. But sadly, fighting is not always successful, and when it fails to protect, it can result in a form of disability. Initially, humans instinctively avoid this by taking preventive measures and relentlessly searching for a cure. However, when all hope is abandoned, we ultimately accept it. Interestingly, Pacific Rim illustrates this cycle: destruction, protection, and ultimately redemption.

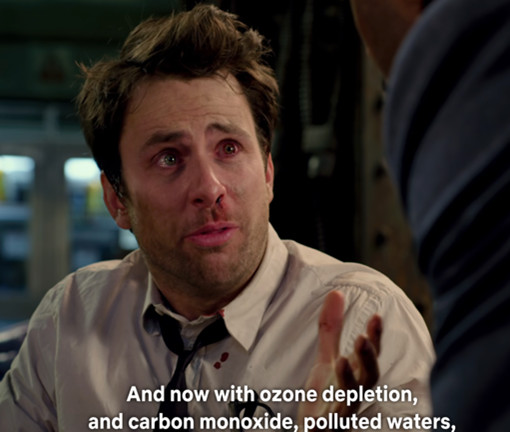

Kaiju act as a foreign organism and are often portrayed as an invasive actor that incites fear and intimidation, exacerbated by their monstrous size and appearance. This sense of disruption mirrors Taylor’s (2024) concept of “disabled ecologies,” which recognize the intertwined harms affecting both human communities and the environment. This framework emphasizes that everything is interconnected, making it impossible to separate human and natural systems. The kaiju are a new organism introduced in Pacific Rim that is not originally part of the ecosystem, creating destruction. The appearance of the kaiju presents an ironic twist: while most non-native organisms that enter an ecosystem cannot survive and ultimately die, the kaiju not only endures but thrives, feeding off the damaged system and seeking to become part of it. As one of the scientists said in the film, we made the earth fertile for the kaiju to live on, laying out all the toxic waste as a product of corporate greed (refer to Fig.1).

Pacific Rim (2013)

Pacific Rim (2013)

It highlights the irony that while ordinary organisms perish in polluted or damaged environments, kaiju are drawn to and even embrace ecological harm, positioning themselves as agents or products of environmental catastrophe. The kaiju amplifies Taylor’s framework by embodying the complex and paradoxical consequences of industrial harm within disabled ecologies. It helps to shed light on the monstrous entanglements, revealing the unpredictable adaptations that result from environmental destruction. The kaiju powerfully symbolizes the monstrous byproducts of unchecked industrial and human activity, transforming invisible environmental harms into something tangible and impossible to ignore. By personifying these hidden consequences, the kaiju makes the scale and impact of environmental destruction strikingly visible.

Posthuman: Adaptive Extensions and Survival

In the world of Pacific Rim, kaiju are depicted as a new contender for colonizing the earth with their own agenda. Humans assume the role of a conservative elite with the primary goal of defending the earth against the kaiju, which are perceived as “invasive species” aiming to colonize and build a new world. In ecology, invasive species are known to cause harm whenever they are introduced into a new environment, which can threaten the “native” species and lead to extinction (National Ocean Service, 2024). In this vein, the presence of kaiju as an invasive species wreaking havoc on Earth poses a threat to the humans’ habitat, enabling humans to adapt, transform, and extend their limitations. This ultimately led to the development of Jaegers, a two-pilot drift mechanic, and an extractive labor system built around the exploitation of kaiju remains as coping mechanisms.

The Jaeger program, known as the Pan Pacific Defense Corps (PPDC), is a transnational coalition established in the Pacific Rim in response to the invasion threat posed by the kaiju. It illustrates a semblance of the Kaiju Economy, showing how global networks function to turn a disaster into an opportunity, which can also serve as a metaphor for how industrial corporations profit from impairment. It parallels how the construction of military aircraft introduced contaminants in the aquifer of Tucson, Arizona, as part of the United States' World War II military efforts (Taylor, 2024). The Jaeger program can be linked to Haraway’s (1992) work on “the promise of monsters”:

refiguring the actors in the construction of the ethnospecific categories of nature and culture. The actors are not all “us.”...not all of them human, not all of them organic, not all of them technological. In its scientific embodiments as well as in other forms, nature is made, but not entirely by humans; it is a co-construction among humans and nonhumans. (1992, p.462)

In the film, Jaeger pilots become posthuman extensions, adapting through the neural Drift system, sharing one brain and embracing entanglement. The mecha-style costume also serves as a posthuman identity developed as an adaptive form of survival to combat the kaiju: a power-up transformation that mitigates the risks. In this context, disability is reanimated as a point of connection and not contention.

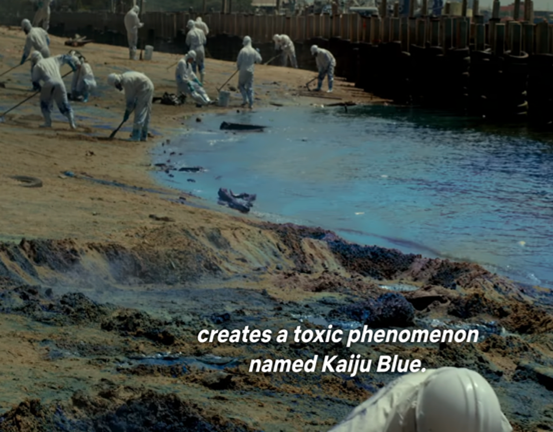

Pacific Rim expands the storyline of the kaiju genre by establishing a framework and narrative for after a kaiju is successfully eliminated. Usually, kaiju films end when the “monster” is successfully annihilated. Del Toro further broadens this by incorporating real-life issues, such as environmental consequences, through the concept of Kaiju Blue, a toxic waste left behind by the monsters (Fig.2). This concept also pays homage to previous kaiju films that addressed nuclear trauma, allowing Pacific Rim to fit into the larger global genre. Del Toro has a layered approach by featuring the exploitative practices of capitalism.

Pacific Rim (2013)

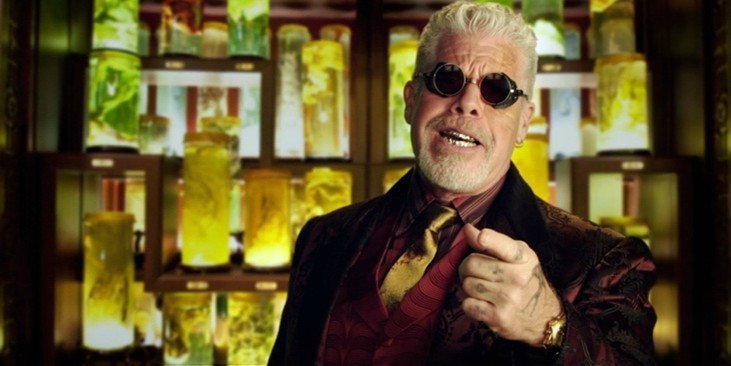

The death of a kaiju itself becomes a form of extraction. The introduction of Hannibal Chau (aka Hellboy) is a perfect fit because he can highlight the moral ambiguity of the characters he portrays, as a flamboyant black-market entrepreneur who successfully built a profitable business against these invasive species. Kaiju, in this view, are torn apart, broken into pieces that are harvested, experimented on, and become a commodity. This is reminiscent of the human experiments that blur the line between what is accepted and what is not.

Thinking on eugenics and mind melding also unpacks the dark history of non-human experimentation, linking to a Russian scientist, Vladimir Demikhov, who grafted two dogs into one body and was later recognized for transplant studies (Monasterio Astobiza, 2018). Stretching this further reminds me of a popular Japanese anime called Full Metal Alchemist: Brotherhood. In one episode, Nina Tucker fuses with her beloved dog, Alexander, to become a monstrous chimera, a transformation performed by her scientist father to maintain his State Alchemist license. These posthuman extensions can reflect two things: The Jaeger program exemplifies the good, with transnational cooperation aimed at common benefit. On the other hand, the underground business of kaiju extraction exemplifies the ambivalent nature of working with non-human actors and human’s adaptive response of survival.

Conclusion

“You have to believe in something to see it” is a saying that reflects human skepticism. Contaminants and monsters are often perceived as a product of our imaginations. The industrial age produced harmful chemicals that act as contaminants, polluting our water and air. These chemicals are often so microscopic that our naked eye cannot see them. And so we deny their very existence to hide a problem that we choose to ignore. These hidden dangers lead to invisibilities and inconveniences that create ripple effects and disabilities, which we instantly see as imperfections simply because they don’t adhere to the standard that we all know (Taylor, 2024, p.30). Kaiju are fictional representations that we make into film and cultural icons to make something intangible, tangible.

Recognizing environmental harm requires confronting inconvenient truths. Al Gore’s climate change documentary An Inconvenient Truth (2006) reminds us of facts and truths about how toxic mass waste alters the only planet we inhabit, yet a lot of corporations today still practice greenwashing and are motivated by corporate profits despite knowing the facts (Lyons, 2019). Disabled ecologies also pose inconvenient truths, such as the reality of polluted contaminants in Tucson's aquifers, which is an enduring consequence of postwar efforts in the 1940s. It illustrates a grim history of denial and corporations hiding behind myths such as “they didn’t know better back then” and “lack of experience” against the mounting evidence. This is just one case of many. Beyond the kaiju’s known metaphor, it also serves as a reminder of how humans choose to set aside facts and inconvenient truths for temporal benefits, which later evolve into a monstrous disaster we can no longer contain. The idea that humans, known as custodians and protectors of the earth, become prey is a reversed take on the return of the repressed, as they become victims of their own actions.

Do we need to fear the “monsters,” the kaiju? Or do we need to rethink how we perceive their presence because they make inconveniences and harsh realities visible? Do we wait for problems that require evangelical technological advancement? Or should we embrace the unknown by doing the hard work now rather than later? We must recognize things that are disabled and in the periphery, and we must be reminded that meritocracy and standards are socially constructed, despite how much value we put on them. It’s about expanding our understanding and resisting conforming to norms, by being comfortable with logic, and ultimately challenging and questioning how things are. Social norms offer only a compelling facade by presenting themselves as the right choice, seeking comfort in the approval of others as a form of self-preservation. Kaiju is a form of disabled ecologies that welcome and acknowledge differences, embrace discomfort, and have their own timeline. It is a connection that paves a path to recognize the uncanny and peculiar, going beyond the awareness that it exists to embrace it fully. It represents the subconscious urge to ignore visible threats, even as it loudly reminds us not to repeat past mistakes and become a cautionary tale. Understanding disability in all its forms (non-human and human) expands our tolerance and acceptance, allowing us to welcome differences and challenge our own conception of fear.

References

Arakawa, H. (Writer), & Satō, Y. (Director). (2009). The older brother (Season 1, Episode 4) [TV series episode]. In H. Suzuki (Producer), Fullmetal Alchemist: Brotherhood. Bones.

Barr, J. (2016). The kaiju film : a critical study of cinema’s biggest monsters. McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers.

Bong, J. H. (Director). (2006). The Host [Film]. Showbox Entertainment; Chungeorahm Film.

Del Toro, G. (Director). (2013). Pacific Rim [Film]. Warner Bros. Pictures; Legendary Pictures.

Haraway, D. (1992). The promise of monsters: A regenerative politics for inappropriate/d others. In L. Grossberg, C. Nelson, & P. Treichler (Eds.), Cultural studies (pp. 295–337). Routledge.

King, H. (2021). The Host versus Cloverfield. In S. J. Miller & A. Briefel (Eds.), Horror after 9/11 (pp. 124–141). University of Texas Press. https://doi.org/10.7560/726628-008.

Lyons, J. (2019). “Gore is the world”: embodying environmental risk in An Inconvenient Truth. Journal of Risk Research, 22(9), 1156–1170. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2019.1569103

Monasterio Astobiza, A. (2018). The Morality of Head Transplant: Frankenstein’s Allegory. Ramon LLull journal of applied ethics, 9(9), 117–136.

National Ocean Service. (2024, June 16). What is an invasive species? NOAA. https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/invasive.html.

Reeves, M. (Director). (2008). Cloverfield [Film]. Paramount Pictures; Bad Robot Productions.

Taylor, S., & EBSCOhost. (2024). Disabled ecologies : lessons from a wounded desert. University of California Press.

Biography

Joy Hannah Panaligan is a doctoral student at USC Annenberg. Her research interests broadly concern platform labor and labor in emerging digital technologies. Her scholarly interests also include casual video games, films, and science fiction.