On Parasocial Relationships with Professional Athletes

/The following post was created as part of the assigned work for Henry Jenkins's PhD seminar, Public Intellectuals. The goal of the class is to help communication and media studies students to develop the skills and conceptual framework necessary to do more public-facing work. They learn how to write op-eds, blog posts, interviews, podcasts, and dialogic writing and consider examples of contemporary and historic public intellectuals from around the world. The definition of public intellectuals goes beyond a celebrity-focus approach to think about all of the work which gets done to engage publics — at all scales — with scholarship and critiques concerning the media, politics, and everyday life. Our assumption is that most scholars and many nonscholars do work which informs the public sphere, whether it is speaking on national television or to a local PTA meeting.

I might owe my sister an apology.

My family have always been fans of the Philadelphia Eagles. To most Philadelphians, being an Eagles fan means more than just supporting our favorite football team: it’s a lifestyle. We bleed green, as they say. Generations of children have been raised on the grit and fire and defiance offered by Eagles teams. We’ve formed a collective identity and earned notoriety around being underdogs in the National Football League (NFL), the brash and bare-knuckled bullies who always have to scrap for what we deserve. It’s always been us vs. everybody.

So when my sister brought home an Odell Beckham, Jr. jersey several years ago, I was mortified. Not only did he play for the New York Giants, our football rivals since the beginning of football, but he was an extremely skilled, lightning-fast receiver who always seemed to have our number. I was furious when I saw her holding that horrible red and blue jersey. In my memory, I ranted and raved for days. I knew OBJ was an exciting athlete to watch, but was he worth compromising our values? How could she ever cheer for a Giants player? Who did she think she was, bringing that into our house?

Figure 1: Odell Beckham, Jr. (OBJ) catching a touchdown over an Eagles player. Image by USA Today (2016)

It wasn’t until years later that I realized she had recognized something crucial about the changing landscape of American sports fandom: people invest a lot more into individual players today than they have in the past.

American sports fandom: from team to player

In years past, sports fandom was strongly defined by location, and people generally cared more about their favorite teams than their favorite players. Many of the fiercest rivalries in NFL history, for example, have been predicated on proximity. There are only 184 miles between the home stadia of the Green Bay Packers and the Chicago Bears, the two titans of the NFL’s most notorious rivalry; only 85 miles separate my Eagles from the Giants’ home at MetLife Stadium. In the past, fans chose a team and stuck with it, and it was easier to stick with a team whose fanbase was local.

That trend seems to be shifting for sports fans lately. Brendan Dwyer (2011) explored some of these changes in their piece on evolving fan loyalty: they argued that digital sports technology, in particular fantasy sports, could shift our fannish sentiments from team-based to player-oriented. In the fantasy sports context, competitors win points based on the athletic performances of the players they’ve chosen. Players gain more points for the ‘managers’ of their fantasy team by putting up better stats, and they lose these ‘managers’ points by making in-game errors. More than ever before, we’re closely following and monitoring the input of individual players.

This evolution to player-based spectatorship has fascinating implications for the relationships between professional players and sports fans. Many of us watch teams we don’t even like simply to observe their star players in action. The Milwaukee Bucks aren’t a worthy spectacle without Giannis Antetokounmpo; the Memphis Grizzlies don’t make headlines, but Ja Morant does. We should expect this increased scrutiny of individual players over teams to impact fannish perceptions of those players, but it’s unclear right now exactly how these changes across sports leagues have shifted fans’ parasocial relationships with athletes.

Parasocial relationships with athletes

The term “para-social relationship” was first seen in a 1956 publication by Donald Horton and R. Richard Wohl wherein they analyzed mass media and how consumers relate to personas. Parasocial relationships are imagined connections between us and people who don’t know we exist; they are, in essence, our manifestations of the assumed intimacy between us and the people we see on our screens. These (generally one-sided) relationships exist, as Horton and Wohl would say, “between spectator and performer.” Horton and Wohl argued that parasocial relationships can be considered part and parcel of a normal life, tools that can help us understand ourselves socially in relation to others. They also, however, cautioned readers against developing intense parasocial relationships that obscure the realities around us.

Parasocial relationships can look different in different contexts. Some of us have posters of our favorite performers on our bedroom walls. Some of us consider ourselves part of a global fan network, a hive of sorts, united through the common goal of defending our ‘faves.’ Some of us just really, really like watching Bob Ross videos. Even if we haven’t called them by their name, parasocial relationships exist all around us and have for a long time.

Figure 2: Michael Jackson live in Bucharest for the Dangerous tour. Video from YouTube

We’ve clearly developed parasocial relationships with professional athletes and other celebrities in the past, well before social media and sports tech. As a student in Los Angeles, I can’t help but think of the public allure of athletic personas like Earvin ‘Magic’ Johnson, O.J. Simpson, and LeBron James. These figures can be thought of as having transcended the typical mold of the athlete; they don’t just “shut up and dribble”, they evolved to represent something personal, powerful, and intimate for the fans who follow them.

Figure 3: Messages of support outside O.J. Simpson’s home in Los Angeles. Image by Steve Granitz/WireImage

Figure 4: LeBron leaves the court after a game against the Phoenix Suns, Nov 12, 2019. Image by Christian Petersen/Getty Images

New sports media and technology

We’ve clearly been fostering parasocial interactions with professional athletes for a long, long time now. However, new media and technologies are drastically changing our relationships to professional athletes, and quickly. Our modern mediascape looks completely different than it did even just five or ten years ago, and our parasocial relationships have become much more complicated as a result. Sports tech like fantasy football has arguably driven the move from geographic team fandom to player-based fandom, but most academic studies on sports fandom couldn’t have anticipated, for example, the legalization of sports betting in the U.S. in 2018. Fans now have skin in the game like never before, which has changed the ways we interact with pro athletes and how we allocate blame for our financial decisions.

Figure 5: Highway billboard that reads: “WHY SHOULD VEGAS HAVE ALL THE FUN? DRAFTKINGS SPORTSBOOK IS COMING TO NJ.” Photo by @readDanwrite on Twitter.

Though the legality of sports betting is ultimately decided by each individual state, the digitization of the practice allows fans to place bets from virtually anywhere. And people don’t just make bets on teams: parlays and prop bets make it easy to bet your money on the performance of an individual player. If I as a fan bet my own hard-earned money on LeBron grabbing 8 rebounds and he only manages to pull down 7, I’m gonna have way more of an issue with him than I would have, had my money not been on the line. Social media sites represent the perfect platform for fans who’ve lost money betting on sports to speak directly to professional athletes.

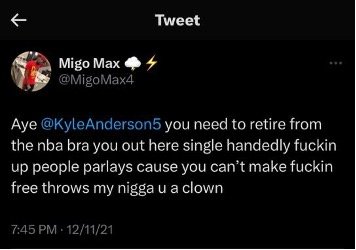

Figure 6: Fans use Twitter to express their frustration with player insufficiencies around betting.

To add to all the commotion, the modern mediascape has done more than enable us to speak with athletes: it’s granted athletes the space to speak back to us. I’ve been thinking a lot lately about Lillian Feder’s (2020) research on the COVID-19 pandemic and athletes. They found that “heightened online interaction between professional athletes and fans [during the pandemic] has served to strengthen their existing parasocial relationships.” Feder went a step further, though, to clarify that the relationships between the two groups haven’t just been fortified as a result of this heightened online interaction: extraordinarily, they’ve begun to trouble our core understanding of what constitutes a parasocial relationship in the first place.

If we’ve read up on our Horton and Wohl, we understand parasocial relationships as providing the illusion of intimacy, but the combination of social media and the COVID-19 pandemic have created an environment wherein these relationships are more than just one-sided or imagined. Now more than ever, we’re not just tweeting into the void when we slander athletes and other celebrities online. Whether consciously or not, we’re engineering and maintaining social spaces around sports fandom that defy what we’ve collectively understood to be parasocial. Professional athletes (and mutual relationships with them) are no longer out of our reach.

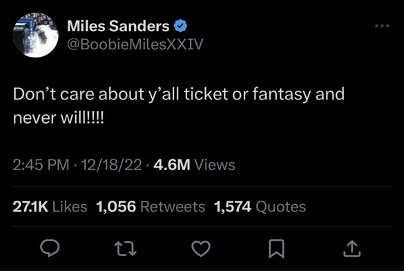

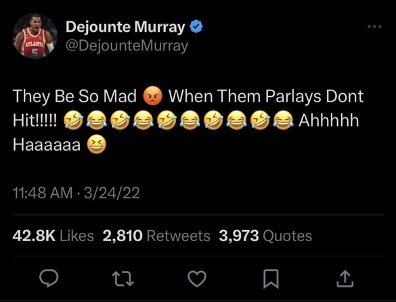

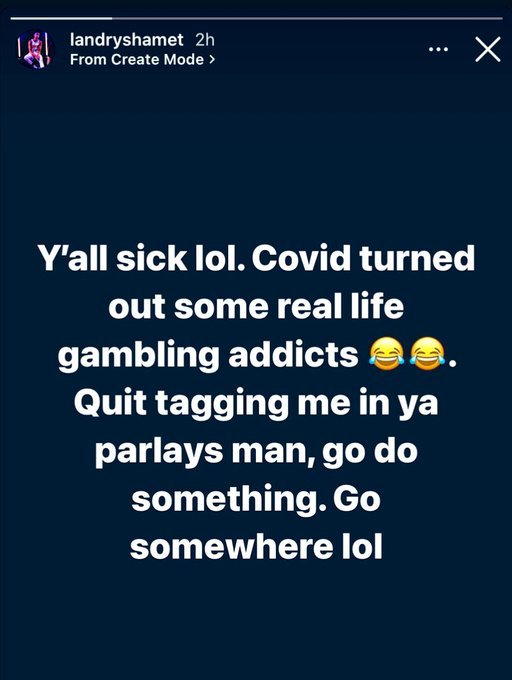

Often, these athletes have expressed frustration and disdain with new fan practices around betting. Apparently, they don’t take kindly to being treated as commodity so explicitly.

Figure 7: Athletes use Twitter and Instagram to voice their displeasure with the social habits around fan betting

In a country built on the enslavement of Black people, wherein the most profitable sports leagues are majority Black, sports betting stands to represent a slippery slope in regards to race and labor. Those tensions are not easy to untangle. It is critical to explore fannish responses to new sports technologies; however, we are in clear need of an intervention around the ways we think and talk about the bodies of athletes, and it is necessary to learn more about athletes’ responses to the changing shape of sports fandom.

Final thoughts

Simply put, sports fandom looks shockingly different than it did even just a few years ago. The changing dynamics of fan relationships to players and teams have been intensified by new social modalities and sports technologies. We have muddied the waters around what it means to have a parasocial relationship with somebody, and we have yet to discover the implications of this cloudiness. Do we need to expand our definition of parasocial interaction to encompass this sort of quasi-reciprocal relationship that exists between professional athletes and sports fans? Or should these phenomena be classified as something else entirely? We have yet to fully understand or describe the impacts of these evolving social dynamics of sports fandom on our relationships with professional athletes.

It’s difficult to admit, but when my sister bought that Odell Beckham jersey, she wasn’t undermining the team-based fandom that I had grown so accustomed to. She was pioneering (in our household, at least) a new way of thinking that reflected modern shifts in fan self-definition. And because she knew something about the changing state of sports fandom that I didn’t quite know yet at the time, I’m happy to offer her my apologies. But I ain’t buying no damn Giants jersey.

Biography

nikki thomas is a Philly sports fan, cat mom, and PhD student at the USC Annenberg School for Communication & Journalism. nikki’s scholarly work revolves around the changing shape(s) of NFL and NBA fandom, with a focus on parasocial relationships between athletes and fans. Recently, they have been dipping their toe into film photography and sports talk radio. Previously, nikki studied education and Africana studies at the University of Pennsylvania.