Contemplating Molly: Notes on Pop-Mart Toys (Part Two)

/While collectors in Japan have historically tended to be male, Pop Mart’s customers from the start have been overwhelmingly young women. These young women have often had to resist parental pressures to marry and settle down in their home towns across China, choosing instead to pursue educational and work opportunities, and thus independence, which has contributed to a wave of urbanization, especially for women, in contemporary China.

Ingyu Oh, Hyun-Chin Lim and Woonho Jang have discussed the feminine appeals of K-Pop music in terms which might describe Chinese fandom as well:

“Assumed to have diverse female identities, all of which are virtuous and ethical, often armed with an unchanging belief in social justice, female universalism in Hallyu is not just about achieving an equal political and hegemonic power in society with males, be that in government offices, business corporations, or the pop culture market, a tenet popularized by the French feminist movement of Parité. Instead, female universalism in Hallyu allows all women in Korean society to achieve their diverse types of personal and social dreams, ranging from personal success to grand social transformations. Therefore, the alternative messages both K-drama and K-pop are delivering to their female fans remain diverse, as long as they commonly espouse the concept of moral and ethical women who are armed with the spirit of social, therefore gender, justice.”

This pop feminism, as Sarah Banet-Weiser notes, often links personal empowerment with consumer culture and the performance of self in everyday life, but given the repressive context in which these Chinese women operate, even these small steps can have transformative effects. Molly’s pink space suit connects her with Barbie in the west, reflecting the fantasy that girls (or in this case, adult women) can do or be anything they want. I recall some of the many cringey comments I have heard through the years from westerners of my parent’s generation, who unconsciously view Chinese women as having the fragile beauty of a “China doll.” Molly offers an image of an, ahem, altogether more plastic feminine identity.

In order to speak to this hip young female consumer, Pop Mart absorbs a wide array of subcultural street fashion, from goth to steampunk, allowing for subtle if not altogether covert signals of affiliation and identity to enter their cubicles.

image 13

image 14

The figures from American, British, and Japanese franchises on Pop Mart’s shelves are only the tip of the iceberg. There are whole malls in Shanghai dedicated to otaku culture, where giant monitors showcase the latest anime, where massive figurines of popular characters allow photo ops, where store after store offer imported cultural goods for consumption, and where these shops co-exist with cat cafes, maid cafes, bubble tea shops, and other elements of Japanese everyday life. Shanghai has more than 400 shopping malls, many of them sprawling and five or six stories tall, so each is seeking ways to distinguish itself from the competition. Leaning into global media fandom has been one core strategy for doing so.

image 15

In the heart of Shanghai there is a full size and garishly colored statue of Evangelion Unit-01. Early on a summer Sunday morning, the statue attracted a mix of young women in Japanese school girl costumes, geeky guys, and a family centered around a young princess in heart shaped sunglasses and a fluffy pink dress. During my fieldwork, I visited cafes dedicated to the Japanese manga omnibus Shonen Jump, the Final Fantasy video game franchise, and the anime series Naruto, not to mention a dojo where Pokémon fans were slapping down cards like an earlier generation might have played with Mahjong tiles. Another mall adopted a more feminine focus, where stalls of K-pop fans sell collector cards and boys love paraphernalia, and shops offer elaborate examples of Lolita dresses and Decora.

IMAGE 16

Keep in mind the complex geopolitical history of China’s relations with Japan, South Korea, the United States, and Great Britain, and you get a sense of the growing generational tensions around these pop cosmopolitan borrowings. The Chinese government worries that they may be losing this generation to outside cultural influences.

State responses mix promoting their own cultural products and repressing fandom around imported cultural goods and practices. In the first instance, we could point to their endorsement of the hangfu movement, where contemporary Chinese people reject modern (and often westernized) garb in favor of traditional design elements from classical Han culture. The Chinese state now embraces this long neglected, sometimes actively discouraged style as a means of rebuilding “cultural confidence” and redirecting the fans’ search for an imaginary elsewhere, in effect, to moments of the nation’s past glory. Establishments have been set up to rent such costumes and apply related makeup and hair styles so that enthusiasts might glide through historic sites, such as restored water villages or cultural museums, though some hangfu elements can be spotted as everyday streetwear. Forward Industry Research Institute (a Chinese research institute) found that by 2020, the number of hangfu enthusiasts in China reached 5.163 million, creating a market size equivalent to US$980 million, a proportional increase of over 40% compared to the previous year.

IMAGE 17

IMAGE 18

Many of the participants have been lured into hangfu culture through their fannish engagement with historical fiction television serials, such as Empress in the Palace, though there are intense debates between fans who seek accuracy and authenticity in their fashion and those who are inspired by the less accurate but more dramatic costumes from their favorite series.

IMAGE 19

IMAGE 20

IMAGE 21

Koitake is a rival of Pop Mart which distinguishes itself with character goods based around Chinese television series and movies – works frequently produced by the state. For example, The Age of Awakening is a dramatization of the early days of the Chinese revolution with young and handsome versions of such venerated political figures as Chang Kai-Shek and Mao Zedong.

image 22

IMAGE 23

How might we compare the sexy young revolutionaries depicted in vinyl with the old-school plaster of paris busts of a grandfatherly Mao which had been an ubiquitous element in China’s official culture a few decades before? The old busts are today often bought for irony or camp, but the new figurines are embraced as part of a growing wave of nationalism and Han supremacy sweeping this same millennial and post-millennial generation while their classmates are bopping to BTS and Black Pink. Do such contradictions arise as a result of the “two economies, one county” policy?

We would scarcely describe her as an agent of propaganda, but my Molly does serve at least one important state priority – the promotion of the Chinese space program. From the moment I stepped off the plane, it was clear China was engaged in an aggressive space race, whether Americans knew it or not, a race with India and Japan, both of whom are putting considerable funds into deep space probes, lunar landers, and ultimately, we expect, manned Mars missions. I have not seen so much popular space related imagery since the NASA moon landing in the 1970s, with significant portions of their toy stores given over to detailed models of various space vehicles or to more playful evocations of the astronaut, such as Pop Mart’s various space-woman Mollys.

IMAGE 24

image 25

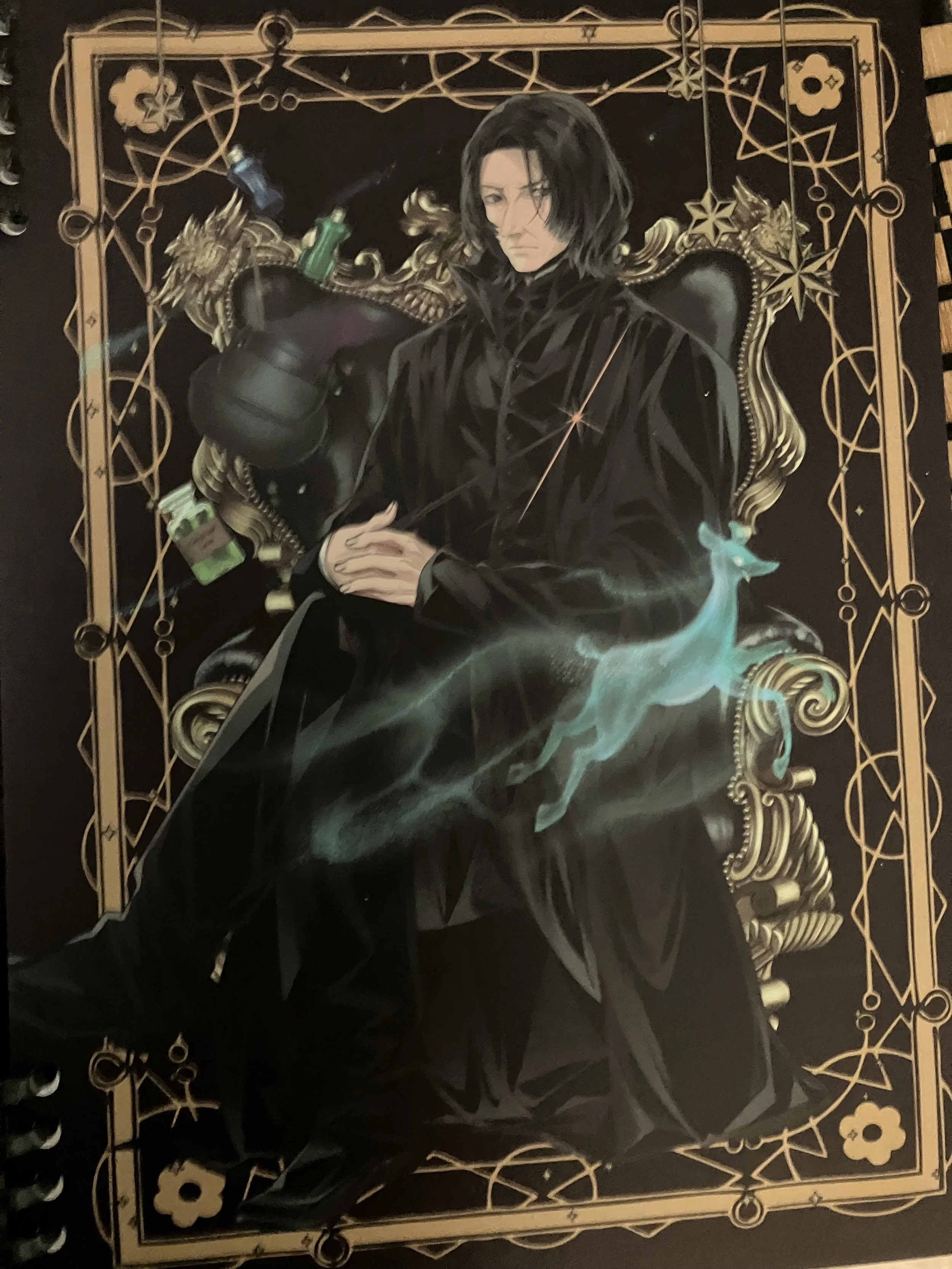

Moreover, Pop Mart’s products may help us to understand how processes of g/localization may shape this struggle between national cultures and anxieties about cultural imperialism. Each of the major East Asia competitors have developed their own styles of cuteness – Kawaii in Japan, Meng in China, and Aegyo in South Korea. While there is certainly overlap in terms of neonatal features and high pitched voices, these different kinds of cuteness rely on different underlying ideologies. Japan’s Kawaii is characterized by an appeal to maternal instincts, the desire to protect and nurture the young and innocent, while as Xaojuan Ma characterizes Meng: “Meng culture signifies young consumers’ emotional needs because, to millennials and Gen Zers in China, Meng culture evokes a restorative feeling through fantasy.” Generally, Kawaii involves simplification, whereas Meng involves ornamentation, as demonstrated by this Chinese produced image of the Harry Potter character, Snape. This helps us to understand the differences in forms of cuteness in Pop Mart’s Meng aesthetic and the Kawaii aesthetic of the Funko Pops that have been such a craze in America for the past decade or so.

IMAGE 26

Another pleasure of a Pop Mart toy rests on its intricate details, which invite us to scan it and make new discoveries each time we pick it up. This focus on elaboration reflects an encyclopedic tendency one finds in so many different forms of Chinese art going back to its classical paintings or even the earliest clay or brass pots, themselves sometimes decorated with figures of cats or horses that carry forward to some of the anthropomorphized figures found in the toy shop today. This feature, more than anything else, makes these Chinese toys, much as Barthes sought to demonstrate the cultural dimensions of French toys.

IMAGE 27

image 28