Chernobyl: From Nuclear Disaster to the TV Series, and Beyond – The Importance of Archives in Narrative Construction

/This is the fifth in a series of perspectives on HBO’s Chernobyl.

Chernobyl (HBO, Sky Atlantic 2019): From nuclear disaster to the Tv series, and beyond.

The importance of archives in narrative construction.

Antonella Mascio

University of Bologna

On May 2019, Sky Atlantic aired the TV mini-series Chernobyl, inspired by the events that had really taken place a few decades earlier, in April 1986. The TV series tells the story of the nuclear disaster, retracing its initial stages, up to the trial of people held responsible for the disaster. The attention paid to the historical reconstruction of the events, the use of testimony documents, the reference to names and people who actually made decisions and guided the various operations, together with an excellent script and direction, and an exceptional cast, as in the best Complex TV (Mittell, 2015), have decreed its success at a global level.

The storytelling is based on archive materials to document a social and cultural trauma, which has a significant importance still today. Archive and trauma are therefore two macro references driving the analysis both from a conceptual and theoretical perspective, and for their fundamental role in the narrative, which is necessary in order to achieve the effect of reality found in the TV series. And again, trauma and archive - or rather their viewing and revisiting - do move audience’s groups towards an investigation linked to the places, where the disaster occurred.

1. The event

The event narrated in the TV series is not so too far from our present. This is one of the most staggering disasters in history, still alive in the collective memory. Chernobyl has had such an impact that it has become a sort of universal warning. Ulrich Beck defined it as a moment of anthropological shock, which, like other disasters, produced a “collapse of the everyday” and a “crisis of presence” (Beck, 1987). Chernobyl would seem to coincide with the entry into the “nuclear age (...) and the beginning of a social construction of risk realities” (ib.).

In April 1986, the disaster had a very large coverage on the media of the period, so much so that it could be considered a real journalistic and media event: It produced breaks in television programming and had consequences in the daily routines of the audiences-citizens, creating new frames of meaning for the notion of “danger”. With Chernobyl, the population was invited to turn their attention to an invisible enemy - radioactive material - which in a short time reached most of Europe, as well as North America. Not only did the media images, the news, inform about the events, but also animate the public debate. The tragedy quickly took on the traits of a global threat, resulting in a strong attention being paid to the possible consequences of the use of nuclear power.

Chernobyl was therefore construed as a catastrophe on various levels: certainly in terms of health and the environment, but also at political and cultural level, by activating an active processing of the accident that modified and gave rise to the assignment of new meanings to the event. In the collective memory, Chernobyl corresponds in fact to a sort of a reference model, to an extreme and fearful event, a negative term of comparison (let us think about the more recent accident in Fukushima), and a form of danger that is extremely difficult to manage, capable of triggering large-scale devastating effects. Still, something that continues to be scary, and from which it is better to move away, both in a physical and symbolic sense. Beck even spoke of a double shock: “the loss of sovereignty is added to the threat in itself, over the assessment of the dangers to which one is so directly exposed” (1987, p. 72), therefore a risk awareness accompanied by a lack of abilities in information management, which is precisely what emerges from the testimonies of the people then living in Pripyat, and collected afterwards (I refer in particular to the book “Chernobyl Prayer: Voices from Chernobyl” by Svetlana Alexievich).

2. Archives and reality effect

A large repository of materials about the disaster was then created in a very short time. From amateur and media images, to audio-videos recorded in the period following April 1986, to written testimonies, or recorded on tapes, all have merged into a sort of archive – more widespread than established - regarding the event. What is the archive and how can it work?

The archive responds to multiple functions: it is configured as a complex tool, a device capable of containing materials that are available to be re-processed and re-designed each time, to give life to new possibilities of reading and interpretation. A device that is also used to generate future stories. How important were the archives in the making of the TV series Chernobyl? The TV series tells the story of Chernobyl through a treatment of the testimonies of several men and women, specifically highlighting the sacrifice they made to save the whole of Europe from a nuclear disaster. The description of the events comprises a scientific level, presented on the screen via the voice of characters representing that world; a political level, through the party representatives of the then-USSR who took action in their various capacities, and who found themselves having to make immediate and difficult decisions. Finally – last, but not least – an emotional level, devoted to feelings, fears, pains expressed through contextual images and characters involved in the disaster. This is then a storytelling that applies its model of reference to the notion of “complex” logic: the viewers are invited to follow the evolution of events, step by step, according to a timeframe that is anything but simple. Each step is connected with a wide series of variables touching the three levels described above, and producing effects on each of them. A drama that focuses its storytelling on the rush against time in order to curb damage and its related loss of lives by men and women, as well as on the search for accountability.

The story is being told as a docu-drama: its purpose consists in bringing a realistic story to the screen, in which the search for the real - or truth - is part of its poetics. The use of statements made by first-hand witnesses, who felt the brunt of the tragedy on their own skins, is in fact well mixed with the typical devices of the audio-visual storytelling. All of this determines a narrative construction based on a constant balance between historical sources on the one hand, and plausible - and partly fictionalized – descriptions, on the other hand. The presence of different narrative levels contributes to the setting up of an articulated view of what happened, following the stories of different characters. Chernobyl - therefore - is not just the story of the nuclear disaster: it is an in-depth plunge into a specific historical moment, where a series of changes were taking place, both at a geo-political and socio-cultural level. Drawing on sources that tell the experience of the people who participated in those events, the series can only be a choral story, composed of the reconstruction of many voices and different points of view on the events.

The development of the narrative, therefore, rests on two fundamental parallel lines: historical sources, enriched by the reconstruction of locations, buildings, streets, cars that bring back the typical looks of countries in the Soviet Union in those years. Thus, the settings reproduce a scenario similar to the real one, and tell a lot about that event, constantly soliciting collective memory through recollection. With the passing of time, some areas in Chernobyl and Pripyat have become a symbol of a shared tragedy and trauma (for example the Ferris wheel - in addition to the power plant).

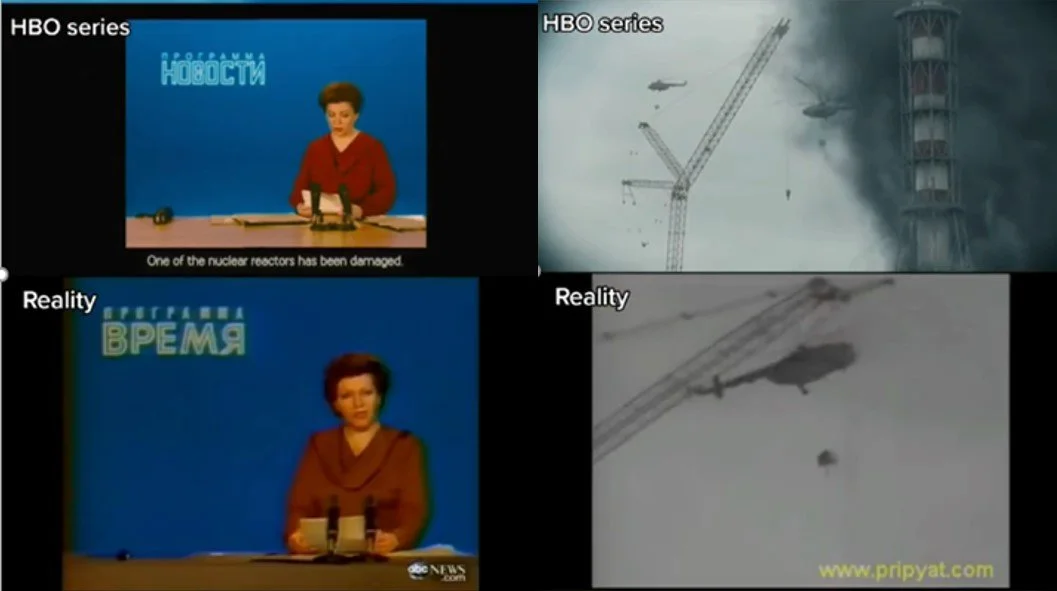

The reconstruction of the atmospheres is achieved through an accurate description of the spaces, furnishing and clothes of the characters. A description that in some passages may perhaps appear even excessive in the meticulous research of the details. All of this is certainly part of the poetics of the TV series, and it helps to produce that effect of reality (Barthes 1988) that brings about an additional level of signification. In effect, Chernobyl presents a narrative basing much of its effectiveness on descriptive expedients: This is not a “detective” TV series or science-fiction. Its reference is an event that we are aware of, and has become part of history books. And what is highlighted, precisely to make the storytelling more realistic, are the details taken from reality or based on archival materials.

References

Alexievich, S. (2016), Chernobyl Prayer: A Chronicle of the Future, Penguin, London.

Alves, E. (2015), “The Specter of Chernobyl: An Ontology of Risk”, in I. Capeloa Gil and C. Wulf, Hazardous Future, Berlin-Munich-Boston, De Gruiter, pp. 127 – 136.

Barthes, R. (1988), “L’effetto di reale”, in Il brusio della lingua, Einaudi, Torino.

Beck, U. (1987), “The Anthropological Shock: Chernobyl And The Contours Of The Risk Society”, Berkeley Journal of Sociology, Vol. 32, pp. 153-165.

Braithwaite, R. (2019), “Chernobyl: A‘Normal’ Accident?”, in Survival, vol. 61, n. 5, pp.149-158 (https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00396338.2019.1662152).

Click, M.A., Scott, S. (2018) (edited by), The Routledge Companion to Media Fandom, New York – London, Routledge – Taylor & Francis Group.

Demaria, C. (2012), Il trauma, l’archivio e il testimone. La semiotica, il documentario e la rappresentazione del “reale”, Bologna, Bononia University Press.

Eco, U. (1979), Lector in fabula, Bompiani, Milano.

Giannachi, G. (2016), Archive Everything: Mapping the Everyday, MIT Press, Cambridge (USA).

Mills, B. (2021), “Chernobyl, Chornobyl and Anthropocentric Narrative”, in Series, vol. VII, n.1, pp. 5 – 18 (https://series.unibo.it/article/view/12419).

Mittell, J. (2015), Complex Tv. The Poetics od Contemporary Television Storytelling, New York University Press, New York.

Rampazzo Gambarato, R., Heuman, J., Lindberg, Y. (2021), “Streaming media and the dynamics of remembering and forgetting: The Chernobyl case”, in Memory Studies, August, pp. 1-16 (https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/17506980211037287).

Robertson, C. (2011), “Introduction: Thinking about Archives, Writing about History”, in C. Robertson, Media History and the Archive, Routledge.

Schmid, S.D. (2020), “Chernobyl the TV Series: On Suspending the Truth or What's the Benefit of Lies?”, in Technology and Culture, vol. 61, n. 4, pp. 1154-1161.

Biography

Antonella Mascio is Associate Professor of Sociology of Cultural and Communication Processes at the University of Bologna (Italy), Department of Political and Social Sciences. She was a visiting scholar at Waseda University, Tokyo, and the University of California, San Diego. Her main research interest is the relationship between TV series and audiences, using a sociological and media perspective, which includes fandom research, fashion and celebrity culture, and nostalgia studies.

She is a member of several Research Centers, including Comedias (https://centri.unibo.it/comedias/it); International Media and Nostalgia Network (https://medianostalgia.org/); Centro di Studi Avanzato Sul Consumo e la Comunicazione (http://www.cescocom.eu/chi-siamo/).

She has published books and many articles in scientific journals and books focused on virtual communities, TV series and their audiences, media, and fashion. She is in numerous editorial boards, including Pop Junctions (Henry Jenkins Project).