Global Fandom Jamboree Conversation: Hyo Jin Kim (South Korea) and Kristen Pike (Qatar) (Part One)

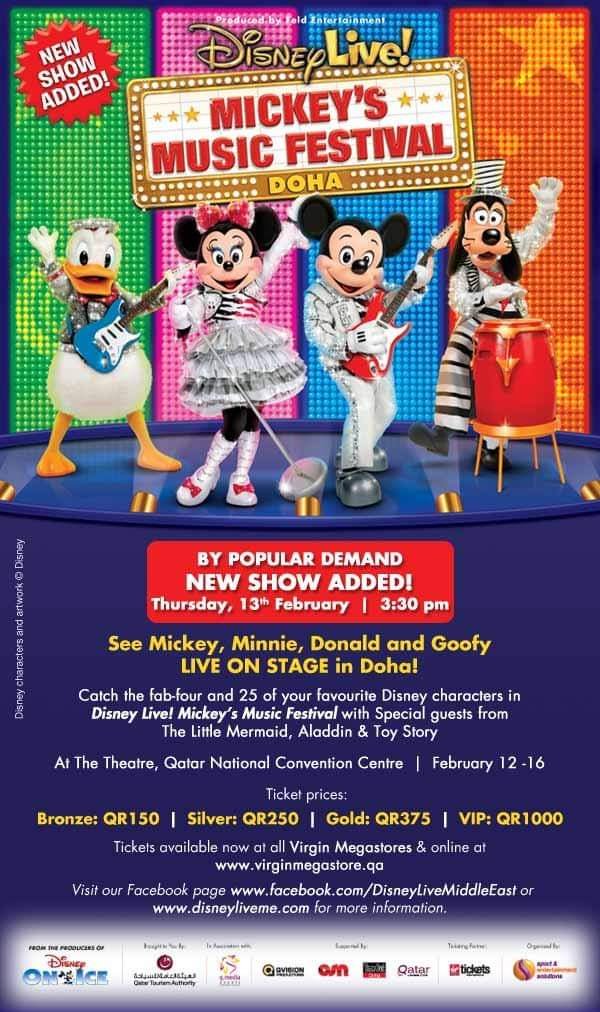

/"Disney Live! Mickey's Music Festival" in Doha, Qatar in 2014

Dear Kirsten and everyone,

I am very happy to be part of this Global fandom project, discussing Disney princesses and their fandom. I was delighted to read Kirsten's opening statement especially Arab females' reaction to these princesses was fascinating. The study results did not report previous media or feminist critics' adverse effects on gender roles, body image, and love interests. Instead, the unexpected and captivating results captured Arab girls' participatory Disney princess culture. Thus, I wonder about Arab female youths and their culture—what makes them create their own princess story, and what is in it? Per Kirsten's study, girls enjoy and consume Disney princess media and products and use the content to create another cultural product incorporating "their gendered interests and concerns." This makes me wonder about Arab girls' gendered interests and concerns. It would be interesting to compare Disney princess fandom in different countries/cultures if possible. Each culture may consume these princesses differently. I want to know these differences and their makeup.

What strikes me is that the girls' storytelling is riveting. This is the part where participatory fan culture steps in. A couple of questions pop up. First, how did these girls know or notice their gendered interests and concerns relative to Disney princesses? What are these gendered interests and concerns? Second, what made these participants very creative and active in telling their stories? These questions may reveal the possible factor for these young female participants' creativity and feministic activity. Did specific social changes or the school system encourage them? What of generational influence (for example, their parents' feministic awareness compared to the previous generation)? Third, why did Arab girls create stories? Were there any common themes? Or any specific topics related to their culture? How did they differ compared to Disney's original princess story? I was just excited Arab girls actively recreate their story through Disney princesses. They are not just consuming Disney but also creating their own culture. Understanding Arab girls' Disney fandom can lead to another perspective on Disney princesses. In addition, Qatar's population drives another research idea, comparing other female youth (different cultural-based) of similar age, consuming Disney film/television, such as Asian girls who live in Qatar vs. Arab girls in Qatar. I am interested in how ethnicity or different cultures may affect media consumption.

Another exciting result of the initial study was the top appealing Disney princesses are Cinderella and Belle, and most girls liked a white princess. Although Kirsten's study did not address any influences on body images, growing up with colored skin, and watching and liking white princesses might give different experiences. When I grew up, I remember there was a 'skin color' crayon—the color of white princesses' skin color in Disney films and television, a bright pink—that has disappeared and does not exist anymore in South Korea. I know it is shocking that there was a specific skin color crayon. Although the racist crayon is gone, whitening beauty products are prevalent in most Asian countries. It could be part of imperial Whiteness in Asia. In some way, Disney is still responsible for girls' body image/skin color. I know Kirsten's participants like Cinderella and Belle because of their characters, not their skin color; however, I'd like to know how Arab girls consume the skin colors of Disney princesses.

Disney princesses have changed in three different periods. The first era is Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), Cinderella (1950), and Sleeping Beauty (1959). Thirty years later, the second era included characters from The Little Mermaid (1989), Beauty and the Beast (1991), Aladdin (1992), Pocahontas (1995), and Mulan (1998). The last era's princesses appear in The Princess and the Frog (2009), Tangled (2010), Brave (2012), and Frozen (2013) (England et al., 2011)[1]. Kirsten's initial study falls in the second era. Since the global popularity of Frozen, I wonder if there are any Disney princess trend changes with girls. Alternatively, did previous participants see Frozen or Disney princesses from the same era differently? How do audiences/fans respond to Disney's changes with princesses?

As Kirsten mentioned, organizations such as the Doha Film Institute (DFI) and The Short Film Lab try to make local productions, but they do not do enough to produce local contents. Are there any government support or policies to encourage local media production? I am also curious about how media audiences respond to local productions and the popularity of local media content compared to foreign/imported productions. This curiosity leads me to think that the more foreign/imported media production gets popular, the less chance there will be for local/indigenous media products to be produced based on the media industry perspective. Therefore, I'd like to know the dynamics of the media industry in Qatar, how the government relates to supporting or encouraging local media productions, and how audiences react.

Another part of Kirsten's research topic on dubbing may apply to some countries importing Disney films and television programs, including South Korea. Arab girls' positive responses to "cultural surgeries" are interesting. In the description of participants, they are comfortable with English. As they do not have any language issues and prefer dubbed versions of Disney films and television, it makes me wonder again, what social circumstances support these young female participants? In South Korea, Disney films and television are an excellent way to learn English, relating to higher education fever, especially in English. Parents, kids, and young adults prefer a subtitled version of Disney rather than a dubbed version. However, the value of a dubbed version is crucial, in my opinion. Nowadays, media critics criticize the globalization phenomenon in media wiping out local and indigenous cultures. The translator of Lost in South Korea mentioned the value of dubbing, which is another way to create the show from a Korean perspective. He said dubbing is not just a direct translation of language but also links two different cultures to make sure audiences understand the contents based on their cultural experiences. I agree with him on the value of dubbing; however, the audiences seem to think differently in South Korea. Therefore, some networks air foreign films and television shows in a subtitled version instead of airing a dubbed version. I wonder how general audiences reflect on dubbing and classical Arabic editing.

Dear HJ (and everyone ),

Thanks so much for sharing your opening statement; I’m delighted to have the opportunity to discuss it with you as part of this Global Fandom Jamboree! You raise several interesting points about fans of science fiction (SF) in South Korea as well as government efforts to spark public interest in science culture more broadly. It’s disappointing to learn that the government’s science culture events so far have not included the texts or practices of SF fandom. But you make a great point about how government initiatives might benefit by doing so. To that end, I wondered if you could say more about how you see feminist SF, specifically, in relation to the government’s efforts. For example, to what extent does Korean feminist science fiction work for or against the government’s science discourses? How might Korean feminist SF be utilized to improve the government’s outreach to the public about science, especially women and girls? I’m not sure if any of the science culture events that you mentioned (e.g., the Korean Science Fair) are circulating gender-specific discourses that encourage women and girls to pursue STEM fields; but, either way, it’s exciting to ponder how Korean feminist SF might be harnessed to further promote (or jumpstart) those efforts.

Reading your comments about Dr. Who brought back a memory of when I lived and worked in South Korea for a year in the mid-1990s. At that time, The X-Files was all the rage, and the family I lived with watched a Korean-dubbed version of it. I’m not sure if any of the fans that you engaged with during your research discussed this show, but it’s interesting to think about how and why certain SF TV shows have resonated with Korean viewers at particular historical moments, and why certain SF shows inspire young viewers to go into STEM fields (i.e., the “Scully Effect”).[1] Was there a similar effect on female viewers of The X-Files in Korea? And do we see that effect with Dr. Who? Given your interesting insights about “Whovians,” I was curious how the casting of Jodie Whittaker (the first female to play “The Doctor” title role) on Dr. Who has been received by Korean fans. I would imagine that female fans might have seen this as an exciting update to the long-running series, especially against the backdrop of the gender-related social movements (e.g., #MeToo) that you mention as having contributed to the recent growth of feminist SF in Korea.

I enjoyed learning about your research projects on the two different feminist SF book clubs in Korea. In particular, I was intrigued by the fact that in both clubs, participants felt emotionally distanced from translations of Western SF texts but had a strong affinity for Korean feminist SF texts. To that end, you noted that the expression of specifically Korean sentiments and experiences seemed to resonate more strongly with book club members. I was wondering if you might be able to say a bit more about what those sentiments and/or experiences are, as well as how some Korean feminist SF authors are tapping into them. For instance, are there certain themes and/or characteristics of Korean feminist SF texts that appeal to Korean fans? How are feminist elements in Korean SF similar to and/or different from feminist sensibilities in some of the Western texts that the Korean book club participants engaged with? In addition to the diverse topics that were discussed in the “500 Days’ Journey of Reading Feminist SF” club, it was heartening to learn about how the club functioned more broadly as a safe space for female participants to share their everyday experiences. Out of curiosity, did either book club include male participants? My sense from what you wrote is that these were female-oriented spaces, but if males were participating, I would love to hear more about their interest in and/or views about feminist SF.

In thinking about how feminist SF fandom in South Korea relates to Disney fandom amongst girls in Qatar, what really jumps out at me is how language and cultural specificity seem to be working in each context. While feminist narratives produced by Korean authors appealed more strongly to the members of the two book clubs than translations of Western texts, the girls in my study tended to report the opposite of this pattern when they discussed the original English-language versions of Disney films and TV shows and the versions that were dubbed into classical Arabic (and edited to be more culturally appropriate for Arab youth) by staff at the youth-oriented channel, Jeem TV, in Qatar. While the girls that I interviewed understood that Jeem’s adaptations of Disney content were designed, in part, to help preserve and affirm the country’s Arabic language and cultural traditions, they also felt incredibly distanced from these media texts. This was largely related to the fact that, like most Arabic speakers, they use classical Arabic to write but not generally to speak (using, instead, the khaliji dialect of the Arab Gulf). Thus, Jeem TV’s attempt at “localizing” Disney’s content for the benefit of Arab youth in Qatar (and the broader MENA region) actually created a kind of cultural dissonance, with girls reporting that the dialogue sounded much too formal to be enjoyable. As such, the participants voiced a preference for either the original English-language versions of Disney films and TV shows (which some perceived as the most “authentic”) or the Egyptian-dubbed versions that they encountered on TV or in movie theaters in the early 2000s. Interestingly, a couple of the Qatari girls in my study told me that they preferred the Egyptian-dubbed versions of Disney films and TV shows because the jokes and comedic dialogue were funnier in that dialect than they were in English. Although I’m not exactly sure where this takes us, perhaps language and cultural specificity are topics to consider more fully as we continue discussing fandom across different media texts, cultural contexts, and feminist sensibilities in Korea and Qatar.

Notes

[1] For useful information and statistics about the “Scully Effect” in the U.S., see: “The Scully Effect: I Want to Believe in STEM.” Featuring research by 21st Century Fox, the Geena Davis Institute on Gender and Media, and J. Walter Thompson Intelligence (2018). Accessible at: https://seejane.org/research-informs-empowers/the-scully-effect-i-want-to-believe-in-stem/

[1] England, Dawn E., Descartes, Lara, & Collier-Meek, Melissa A. (2011). Gender role portrayal

and the Disney princesses. Sex Roles, 64(1), 555-567.