The Trans* Fantasy in Harry Langdon’s The Chaser

/In the fall, I taught a seminar on American film Comedy with a particular focus on comic performance and slapstick. I included a range of lesser known figures but I also wanted to represent the big Four silent comedians — Keaton Lloyd, Chaplin, and Langdon. Langdon is often an afterthought these day since modern audiences often find it difficult to appreciate his slow-reaction style alongside the fast rough and tumble of his contemporaries. I ended up selecting The Chaser, one of the films where Langdon directed himself, pushing past the slander that Frank Capra fostered in The Name Above the Title that Langdon lost his way once he rejected Capra’s shaping role. This turned out to be one of the more popular films from the class with students intrigued by its difference from other silent comedy and especially its bold play with gender identity, which has to be seen to be believed. One MA student, Sabrina Sonner wrote an essay on the film as a Trans fantasy which suggests why Langdon may be especially meaningful to the generation coming of age right now.

The Trans* Fantasy in Harry Langdon’s The Chaser

by Sabrina Sonner

Introduction

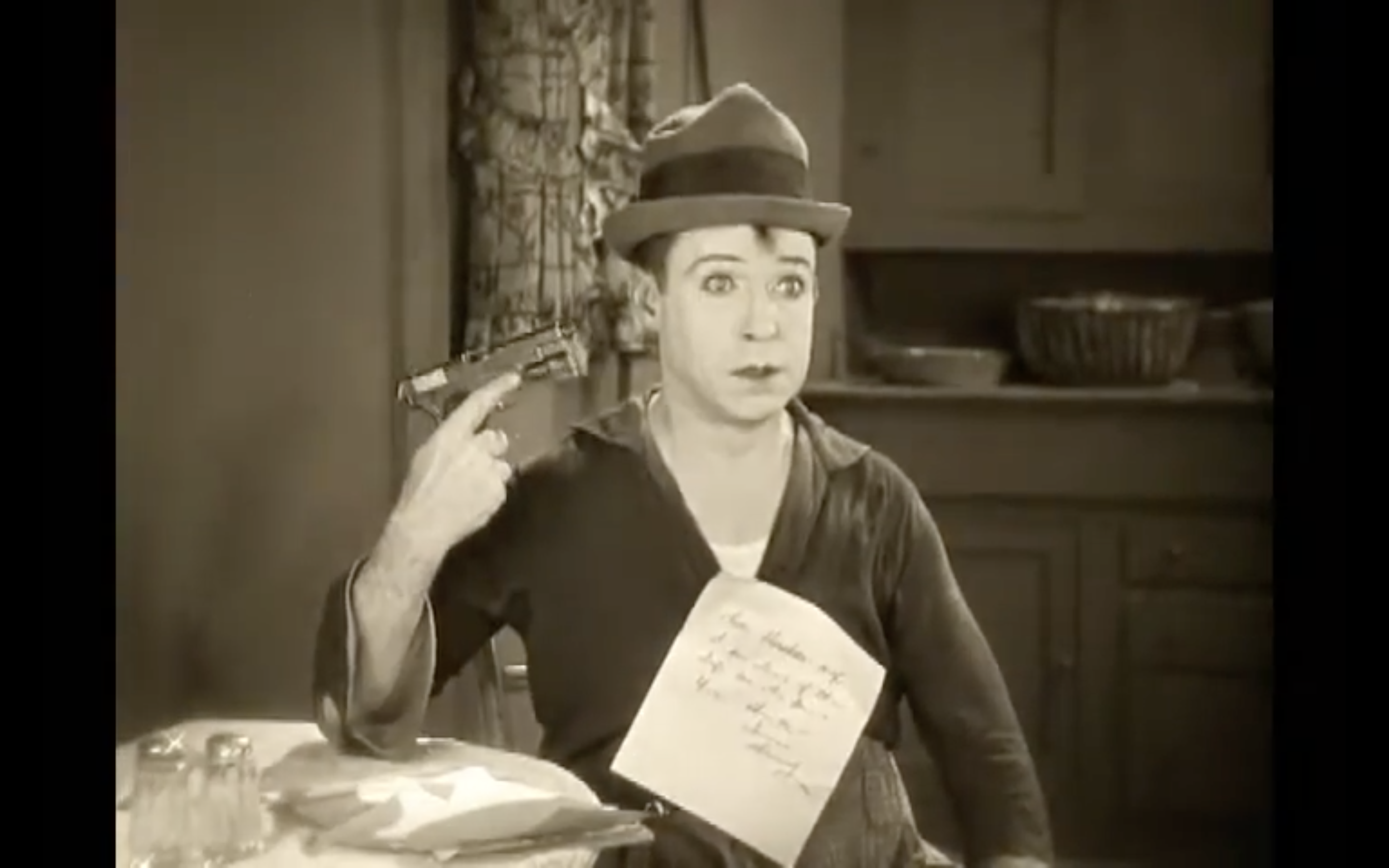

Watching Harry Langdon in The Chaser, I am transfixed by his hat. Throughout the film, he appears as a philanderer in a night club, a guilty husband in court, a wife in the kitchen, a illicit fugitive, a uniformed captain, and a ghost-like apparition. He falls off a cliff in a runaway vehicle, lays eggs, kisses the iceman, and is nearly driven to suicide. And, throughout it all, the hat remains.

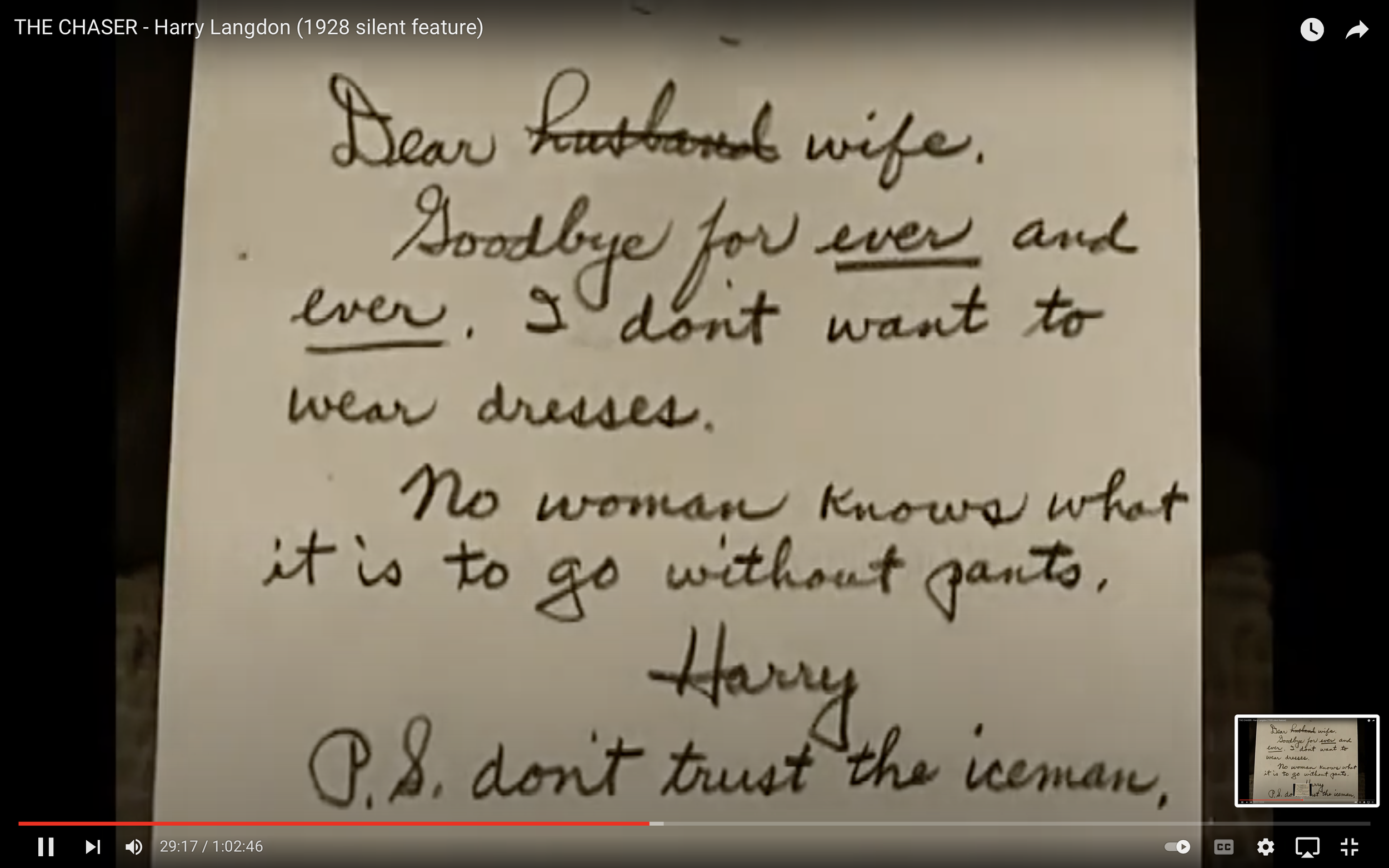

This consistent signifier of his identity stays with him throughout the film, which takes the basic premise of The Husband (played by Harry Langdon) accused of infidelity and court ordered to “take his wife’s place in the kitchen, or serve six months in jail.”[1] He dons a dress and performs his wife’s role, while The Wife (played by Gladys McConnell) takes on her husband’s role. Left at home, Langdon must deal with unwanted advances from the iceman and bill collector. As a result, he tries and fails to kill himself, writing a note that states he is leaving because “no woman knows what it is to go without pants.”[2] At the golf club with his hyper-masculine friend, he rediscovers a masculine uniform, and through a series of mishaps returns home covered in white flour. Though his mother-in-law flees, his wife returns to his arms, and the same intertitle that opened the film closes it, proclaiming “In the beginning, God created man in his own image and likeness. A little later on, he created woman.”[3]

While it may be one of Langdon’s less discussed films, I believe The Chaser opens up unique spaces surrounding gender and identity through interweaving Langdon’s innocent star persona with the potential of comedy to disrupt societal expectations. Within the history of clowns and silent comedians, there exists a power to break away from normative societal values.[4] We see this idea in Langdon’s disruption of gender in the film, as his comedic identity remains consistent while his gender presentation wildly fluctuates. Additionally, the slapstick nature of the film opens up ideas around the body and what it is allowed to do. Though made to dress a certain way, Langdon is still able to freely use his body in the world in a way enviable to a trans* body. In the way Langdon is clothed and in his undamageable slapstick body, a trans* fantasy emerges. What if I could wear a dress and be seen as a woman? Or wear a suit and be seen as a man? The film highlights the absurdity of the world responding to a single gendered indicator so strongly, but also opens up a freeing daydream that asks, “What would happen if we could be seen this way?” Langdon’s body never bruises, breaks, or tears – it behaves how he wants it to. With mine, I consider thousands of dollars of surgery to get it to behave as I wish. In this conflux of gender non-conformity, traditionally gendered clothing, Langdon’s consistent star persona, and a freely controlled slapstick body, The Chaser creates a fantastical trans* space.

In my journey through discovering my identity, I have understood it as the way one sees oneself internally, the way this is reflected to the world externally, and most importantly the way one searches to find a happy combination of the two. To that extent, this essay is structured in those three parts, pulling on theorists such as Jack Halberstam, Teresa de Lauretis, Louise Peacock, James Agee, and Muriel Andrin to connect ideas between comedy and queerness.

Langdon’s Consistent Star Persona and the Queerness of Childhood

Throughout The Chaser, Langdon is depicted with an unwavering consistency through his identifiable comedic persona, including his blank face, childlike innocence, and, of course, that hat. Regardless of his attire in the film, the way in which he comedically responds to situations and the recognizability of his star persona shines through. This sense of his baby-faced naivete is detailed by James Agee is his essay on silent film comedy:

“Like Chaplin, Langdon wore a coat which buttoned on his wishbone and swung out wide below, but the effect was very different: he seemed like an outsized baby who had begun to outgrow his clothes. The crown of his hat was rounded and the brim was turned up all around, like a little boy’s hat, and he looked as if he wore diapers under his pants. His walk was that of a child which has just gotten sure on its feet, and his body and hands fitted that age. His face was kept pale to show off, with the simplicity of a nursery-school drawing, the bright, ignorant, gentle eyes and the little twirling mouth…. He was a virtuoso of hesitations and of delicately indecisive motions, and he was particularly fine in a high wind, rounding a corner with a kind of skittering toddle, both hands nursing his hatbrim.”[5]

In The Chaser, we see this childlikeness in the consistency of his reactions, where he responds with a great deal of perplexity to the absurdity of the situations that he finds himself in, especially gendered rituals. Throughout the film, he seems unable to fully grasp any gendered roles assigned to him, both feminine and masculine. For instance, the charge he faces during the film is that of being an unfaithful or unruly husband. However, looking at the film’s depiction of this behavior, Langdon hardly seems the type. He goes to this club to eat peanuts and watch. Though slightly voyeuristic, this depiction is relatively tame in comparison to the way a philandering womanizer could appear. When he finishes in the club, he then dons a masculine uniform, which fails him in his goals of appearing the idealized husband. He fairs no better when he performs the wife’s role. In his dress, he seems uncomprehending of feminine ideas, such as the cooking behaviors he is asked to take on as well as understanding of reproduction, albeit that of chickens and eggs. When he returns to his masculine attire, he counters the hyper-masculinity of his friend while golfing. Within these scenarios, which are rife with gendered expectations, Langdon always fails to measure up, or even understand exactly what he’s being measured up to.

Langdon’s child-like lack of understanding of gendered norms creates a parallel with Jack Halberstam’s writings on the queerness of childhood. When writing of childhood and its depictions in cinema, Halberstam writes:

“There is nothing natural in the end about gender as it emerges from childhood; the hetero scripts that are forced on children have nothing to do with nature and everything to do with violent enforcements of hetero-reproductive domesticity. These enforcements, even when they can accommodate some degree of bodily difference, direct children toward regular understandings of the body in time and space. But the weird set of experiences that we call childhood stands outside adult logics of time and space. The time of the child, then, like the time of the queer, is always already over and still to come.[“6]

Though Langdon is not a literal child, his childlike nature evokes this queerness. He acts as a receptacle that the world places meaning on. As he attempts to sort through it, he appears as if he’s a child completely unaware of what is expected of him and encountering gendered expectations for the first time. In both his masculinized uniform and feminized wife’s attire, he seems out of place, like a child playing dress-up. Langdon’s character operates in a different logic from the rest of the world and, due to his specific star persona, encapsulates this childlike logic and queer aspect of the time of childhood.

To illustrate the innocence and consistency of Langdon’s comedic persona in a specific example, throughout The Chaser, Langdon has this consistent deadpan reaction, where he faces the camera and blinks a couple times, uncomprehending the absurdity of the comedic bit that just happened. We see this throughout the film as a constant presence, whether he is reacting to a woman falling into his arms when he wears his masculine uniform, the iceman kissing him when he dons a dress, or when he lays an egg. Alongside his ever-constant hat is a solidified comedic identity that refuses to adapt to ever-changing gendered expectations. In Langdon’s confusion regarding the gendered expectations, and the consistency of his identity beneath it all, there is space within the film to question alongside Langdon exactly how valuable these societal expectations are.

Additionally, I would argue that there’s a queerness to Langdon’s body as a slapstick body. His star persona adheres to ideas that Muriel Andrin considers writing of an unbreakable slapstick form:

“These are “bodies without organs,” immune to fragmentation or, when they do suffer fragmentation, insensitive to trauma. They remain whole no matter what the threat, displaying not a permanent moral integrity like melodramatic characters, but a lasting physical integrity… The slapstick world is a perfect place for instant healing.”[7]

There are many ways in this world that the trans* body can find itself under threat or in need of healing, whether it is due to growing rates of violence against transgender and gender-nonconforming people,[8] or trans* bodies themselves being voluntarily surgically modified to better fit one’s gender expression. The idea of the resilient slapstick body appears in The Chaser in a sequence near the end of the film, where Langdon hides in the trunk of a car that topples off a cliff and crashes through multiple billboards into his kitchen without troubling Langdon one bit. In a more serious and subtle way, the scene in which he fails to kill himself in several ways can be read as the trans*, slapstick body resisting its own demise and providing a protection that the individual needs despite their momentary wants.

Altogether, the confused, youthful quality of Langdon’s star persona connects his performance to a queer period of childhood, and the slapstick nature of this comedic body opens spaces for a specifically trans* imagination of the carefree, freedom of physical expression. The internal reflection of identity within Langdon’s star role in this film establishes a consistency and queerness to his self that clashes with the way society views him throughout the film.

Society, Gender, and The Clown Outside It All

While Langdon’s identity remains constant in the visibility of his comedic star persona to the audience, society takes gendered cues from his clothing and behavior and focuses on them to an absurd degree. Additionally, his role as a clown in the film places Langdon as a figure outside of societal boundaries to whom failure is central. Louise Peacock writes of the clown as “an outsider and a truthteller” who can comment on the societies in which they live.[9] Peacock additionally writes of the way failure is a part of clowning:

“Failure or ‘incompetence’ is a staple ingredient of clown performance… Clowns demonstrate their inability to complete whatever exploit they have begun. In doing so they speak to the inner vulnerability of the audience whose members are often bound by societal conventions which value success over failure.”[10]

The failures of Langdon within the film largely relate to his inability to adhere to gendered roles, such as his initial failings at masculinity that bring about the film’s inciting incident and his subsequent failures to perform his wife’s duties in the kitchen. In doing so, he highlights the constructed nature of the assignment of these duties based on gender. He places himself outside of the gendered expectations of society in a literal way in the opening scene, where he appears a dance club just to watch the activities. And in the comedic bits of the film, his inability to perform either masculinity or femininity allows the audience to consider the facades of those structures. In watching him actively try to learn and fail at these activities he’s been given based on his gender assignment, there is a trans* understanding of the failure to perform at the roles of the gender one is assigned at birth, as well as the complexity of learning the rituals of one’s own gender.

The failings of the clown echo Jack Halberstam’s considerations of failure and queerness, solidifying Langdon’s placement in the film as a queer, comedic outsider. In Halberstam’s writings on queerness and failure, Halberstam writes:

“The Queer Art of Failure dismantles the logics of successes and failure with which we currently live. Under certain circumstances failing, losing, forgetting, unmaking, undoing, unbecoming, not knowing may in fact offer more creative, more cooperative, more surprising ways of being in the world. Failing is something queers do and have always done exceptionally well; for queers failure can be a style, to cite Quentin Crisp, or a way of life, to cite Foucault, and it can stand in contrast to the grim scenarios of success that depend on “trying and trying again.”[11]

In applying Halberstam’s ideas around failure to the film, we can find joyous resistance in the way that Langdon fails at the tasks placed before him in the film. His placid reactions to his failures allow us to safely fantasize about the possibilities that open up before us if we too embrace this logic of failure.

Further considering the way the world interacts with Langdon by way of his encounters with the bill collector and iceman, we can apply ideas surrounding the technologies of gender from Teresa de Lauretis to the film. Within her essay “The Technology of Gender,” de Lauretis establishes gender as a construction that is inseparably connects gender, work, class, and race, writing, “social representation of gender affects its subjective construction and that, vice versa, the subjective representation of gender – or self-representation – affects its social construction.”[12] Given the complexity with which de Lauretis breaks down the social construction of gender, there is an absurdity to the simplicity to the way gender operates within the film when it comes to passing as a gender within the film. As soon as Langdon changes his clothes, the outside world chooses to see him as a woman. By changing one factor of his appearance, Langdon completely alters the way the world views his gender. In contrast, however, we still see Langdon as himself due to his aforementioned star persona, challenging the notion that gender operates this discretely. While the behavior of the men towards Langdon is largely disrespectful, leering at and nonconsensually kissing him, there is also a small space within these interactions to read an absurd form of respect. They see someone placing a feminine indicator on themself, and despite the obviously visible Harry Langdon beneath it, they choose to treat the individual as the presentation he puts forth into the world. Returning to de Lauretis’ theories, the film itself also operates as a technology that can expand and challenge notions of gender and, through this representation, hope to affect its societal construction.

The simplicity of the direct correlation between Langdon’s changing outfits and the way the world genders him opens up a fantasy that, while absurd, evokes a trans* desire to live within a world that could operate in the way that the world of The Chaser does. In Scott Balzerack’s writing on queered masculinity in Hollywood comedians, he brings up the way that “as a gendered subject, the male comedian rearranges (or, at times, rejects) heteronormative protocols.”[13]Viewing Langdon as a gendered subject within the film, he distorts and evades masculinity and femininity as much as he can, playing within a space that allows him to transform in an almost enviable way.

Unifying Gendered Identity Through a Familiar Spectator

Between the tensions of Langdon’s constant identity to the audience and his shifting gender presentation to the world, one might wonder if the film offers a point of resolution of these external and internal identities. By its closing shot, the film leaves us with an image of Langdon remaining in his dress and hat and reuniting with his wife, who has returned to her more traditionally feminine clothes. Looking back at the role played by Gladys McConnell as The Wife in the film provides the answers and resolution we seek.

At the start of the film, McConnell is seen talking nonstop over the phone at her silent husband, and it is her desire to divorce him that brings about the gender-swapping court order. While nothing in this order explicitly mentions her, in the following scenes we see her partially switch roles with her husband – she wears a blazer and tie with a skirt as an incomplete transference into his role. In this outfit, there are suggestions at her failures at femininity when she finds her husband’s suicide note and, believing him dead, sobs until her make-up runs to a heightened extent. While Langdon’s arc throughout the film depicts him failing at femininity in a skirt, McConnell fails at the same ideas of gender while dressed oppositely. In addition, despite the change in roles, she still sees him as her husband, referring to him as such with her friends later in the film. This contrasts with the starkly shifted view of Langdon’s gender by the iceman and bill collector. The film gives her the power to see his identity through the façade of his clothing. When Langdon returns to the house covered in flour, his mother-in-law runs out in fear of a ghost while McConnell, after a temporary fright, recognizes and embraces her husband.

Within this ending moment, some of the more nuanced ideas of gender within the film come together. After having both the husband and wife change their gendered attires, reuniting them when the wife has changed back but the husband remains the same gives a sense of ambiguity around the return to gendered roles within the film. While there is a normative reading of this ending that reunites the heterosexual couple with each person in their place, the actual execution of it has two femininely clothed individuals reuniting. With McConnell recognizing her husband beneath it all, there is an acknowledgement of his identity separate from his presentation. In the space with his wife, Langdon can be seen for who he is, regardless of how he presents. The film closes on a final shot of Langdon with his usual puzzled reaction to his wife returning to him, albeit with a couple of smiles tossed in. Coupled with the closing title reminding us of God creating man in his image and creating woman later on, there is a hint at the queer, homosocial world predating woman, as well as a challenge to the audience in if these binary viewpoints still hold up after watching a film that so comedically unpacks the artificiality of their construction.

Conclusion

By applying a trans* perspective to The Chaser, we can see the way that the film negotiates ideas gender, considering where it is performative, intrinsic, and a part of one’s identity. While there are complex structures around gender in society, there is something delightfully freeing about the space created by the film. In the comedic failures and childlike incomprehension of Langdon, there emerges a queerness in the film that is only heightened by its preoccupation with gender. There isn’t one specific trans* identity explored within the film, but a variety of resonances that makes an umbrella term more appropriate than a specific notion. For instance, in viewing a fantasy of wearing a dress and being seen as a woman, there’s a trans-feminine fantasy. In the idea that he remains a man beneath his clothing regardless of how everyone views him, we see the opposite in the way of a trans-masculine fantasy. And in his positioning throughout the film that remains as neither successfully the uniformed studly husband nor the submissive wife, but finding peace in his final image of a ghost-like version of himself, there’s a non-binary desire of finding a space separate from any of these rituals. Altogether, the film provides evokes a sense of trans* desire through the absurdity with which its gendered rituals exist, the connection between queerness and comedic failure, and the queerness that Langdon’s childlike persona.

Sabrina Sonner is a recent graduate of the University of Southern California’s Cinema and Media Studies Masters program. Their work focuses on queer studies, interactive media, and media that supports live communal forms of play. They have previously been featured at USC’s First Forum conference in 2021, where they examined late stage capitalism through a playfully destructive reimagining of the board game Monopoly. Outside of academia, Sabrina works professionally in new play development for theatre.

Works Cited

Agee, James. “Comedy’s Greatest Era.” Life, 1949. https://scrapsfromtheloft.com/2019/11/17/comedys-greatest-era-james-agee/

Andrin, Muriel. “Back to the ‘Slap’: Slapstick’s Hyperbolic Gesture and The Rhetoric of Violence,” Slapstick Comedy (AFI Film Readers). Routledge, 2009.

Balzerack, Scott. “Someone Like Me for a Member.” Buffoon Men: Classic Hollywood Comedians and Queered Masculinity. Detroit: Wayne State University, 2013.

The Chaser. Harry Langdon. Harry Langdon Corporation. First National Pictures. 1928.

De Lauretis, Teresa. 1987. “The Technology of Gender.” Technologies of Gender: Essays on Theory, Film, and Fiction. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1-30.

“Fatal Violence Against the Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming Community in 2021.” Human Rights Campaign. 2021. https://www.hrc.org/resources/fatal-violence-against-the-transgender-and-gender-non-conforming-community-in-2021

Halberstam, Jack. “Becoming Trans*.” Trans*: A Quick and Quirky Account of Gender Variability. Oakland: University of California Press, 45-62. 2017.

Halberstam, Jack. The Queer Art of Failure. Duke University Press Books. 2011.

Peacock, Louise, “Clowns and Clown Play,” in Peta Tait and Katie Lavers (eds.), The Routledge Circus Studies Reader. London: Routledge, 2016.

[1] The Chaser. Harry Langdon. Harry Langdon Corporation. First National Pictures. 1928.

[2] The Chaser

[3] The Chaser

[4] Peacock, Louise, “Clowns and Clown Play,” in Peta Tait and Katie Lavers (eds.), The Routledge Circus Studies Reader. London: Routledge, 2016. 90.

[5] Agee, James. “Comedy’s Greatest Era.” Life, 1949.

[6] Halberstam, Jack. “Becoming Trans*.” Trans*: A Quick and Quirky Account of Gender Variability. Oakland: University of California Press, 61. 2017.

[7] Andrin, Muriel. “Back to the ‘Slap’: Slapstick’s Hyperbolic Gesture and The Rhetoric of Violence,” Slapstick Comedy (AFI Film Readers). Routledge, 2009. 232

[8] “Fatal Violence Against the Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming Community in 2021.” Human Rights Campaign. 2021. https://www.hrc.org/resources/fatal-violence-against-the-transgender-and-gender-non-conforming-community-in-2021

[9] Peacock, 88.

[10] Peacock, 86.

[11] Halberstam, Jack. The Queer Art of Failure. Duke University Press Books. 2011. 2-3.

[12] De Lauretis, Teresa. 1987. “The Technology of Gender.” Technologies of Gender: Essays on Theory, Film, and Fiction. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. 8-9.

[13] Balzerack, Scott. “Someone Like Me for a Member.” Buffoon Men: Classic Hollywood Comedians and Queered Masculinity. Detroit: Wayne State University, 2013. 4