Global Fandom Jamboree Conversation: Camilo Diaz Pino, Dima Issa and Wikanda Promkhuntong: (part one)

/Wikanda Promkhuntong:

I am thrilled to read Camilo Diaz Pino’s reflection on the Japanese media flows in Latin America. The situation very much resonates with the case in Thailand where Japanese popular culture has also become ‘the quotidian reality’. When I grew up in the 1980s-90s, the J-Wave hit the teen markets with shops of manga cartoons for rent in every city, along with dedicated TV programmes of Japanese cartoons and all kinds of merchandise. I remember that a group of high school friends traveled to an island to follow their favorite Japanese singers during their stay in Thailand with many stories to share at school. The phenomenon resonates with the growth of K-pop stars in recent years.

What is interesting in the case of Japanese media flow is that this early fandom has evolved into everyday culture. Today, one can find modified/localized versions of Japanese food (sushi, Takoyaki, Japanese green tea) in local markets similar to the local version of French fries, steak and spaghetti. This localized dimension and the way American and Japanese popular cultural products exist alongside one another resonates with Camilo’s remark on the process of localization to the extent that audiences view the imported products on the same level as local media/pop culture.

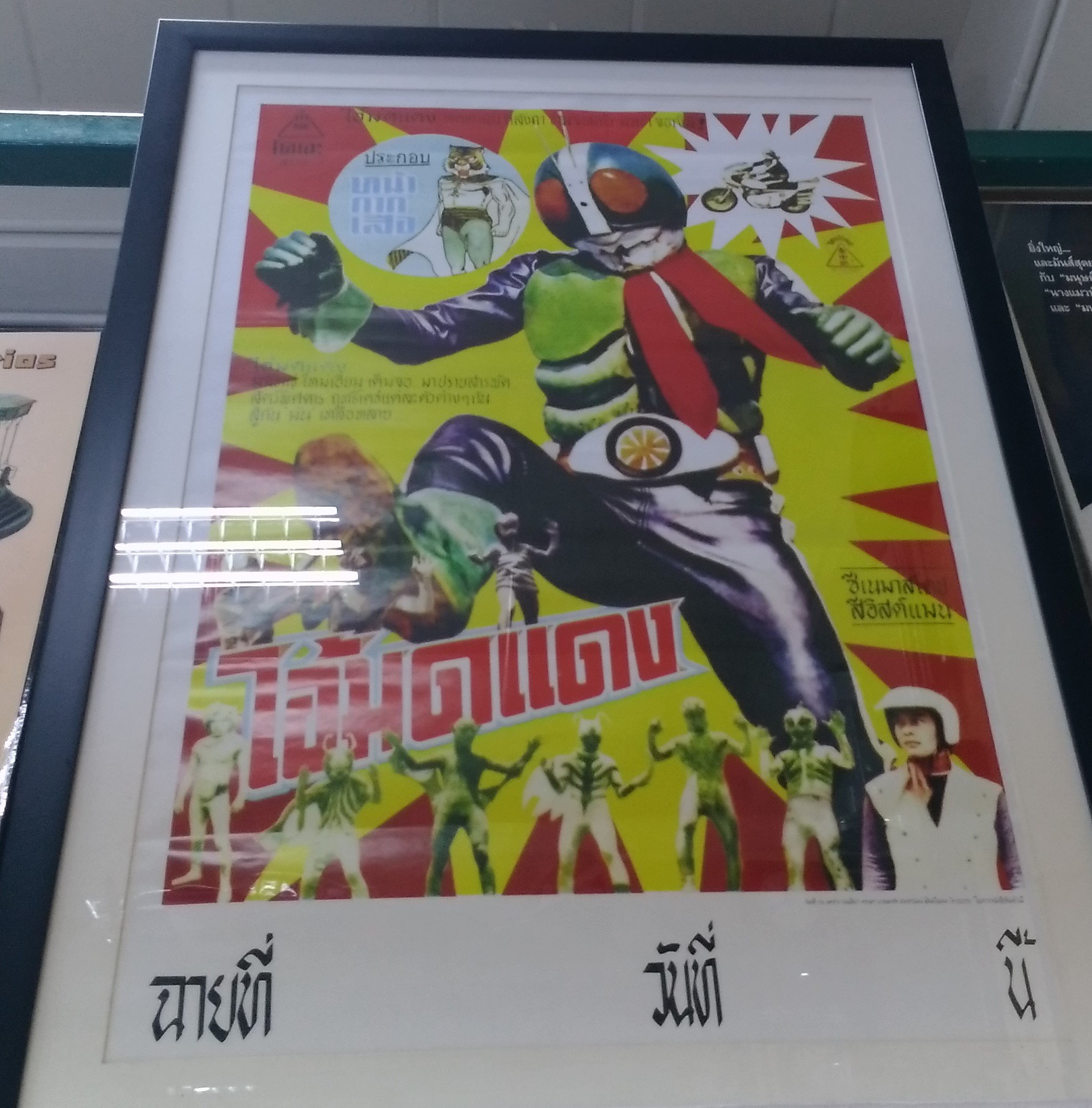

Old LPs and film posters of imported products that were popular in Thailand in the past, taken at Suksasom Museum, one of several collector-owned pop culture showrooms that opened to the public in the last two decades around the edge of Bangkok.

Captain America toy/decorative shield is amongst other everyday items that can be found at local night markets. Image taken at a Khon Kaen Night Market in Northeast of Thailand.

The integration of imported media content and popular culture into dimensions of everyday life including political protests can also be found in the case of Thailand. This includes the use of the Thai version of Hamtaro manga series soundtrack by high school students in 2020 to protest the military-led government. The Thai lyrics of the manga was modified to address the exploitation of tax money while the gesture of a hamster running is adopted into a performative protest run. Another manga called One Piece and the South Korean film Parasite were also drawn on by protesters to criticize the position of elite groups who sided with the military-led government. One of the key figures that pushes for public dialogue on reforming the constitution and monarchy is a human rights lawyer currently under arrest. His performance and speech at a Harry Potter-themed protest is one of the widely-discussed moments of the Thai democratic movement in recent years. The street protests that took place in 2020 in Thailand were multicultural in nature similar to that in Chile with transgender groups, indigenous rights and feminist protesters alongside one another. While the mood and momentum of the protest has shifted with the on-going COVID-19 pandemic, local popular culture and imported ones remain the source for creative civic engagements amongst young people.

Dima Issa’s opening statement on the fandom of Fairouz is also fascinating in many ways. The importance of Fairouz as a public figure reminds me of certain cases associated with fandom in the context of Thailand and Asia. With the growth of East Asian cinema in the global context, the figure of Wong Kar-wai has been the subject of my interest for several years. A number of fan works from different countries have revealed the impact of his films for a range of communities from pan-Asian artists, diasporic Chinese communities and those associated with the sense of alienation and loneliness in global cities. Around the 2010s when I was writing about Wong Kar-wai fans on YouTube, one of the most recurring types of videos found were mashups of sequences from his films with indie music tracks from bands based in the U.S., the UK and Europe revealing the kind of transnational taste homology. In other cases, the association with Wong Kar-wai evolved based on specific geographical contexts of fans. In Thailand, the period of time after the coup when the military was drafting a new constitution and postponed the general election, the term kra-tum-kwam-wong or doing Wong was adopted to describe the mood and feeling of being in a Wong Kar-wai universe with cyclical time and uncertain future. A Facebook page with the same name was created with the mood shifting from expressing individual loneliness through photographs in sepia tone or saturated colors and dim lighting to expressing political discontent.

A pre-screening talk discussing kra-tum-kwam-wong at House cinema in Bangkok before the sold-out screening of the 4K re-release of Wong Kar-wai’s In the Mood for Love.

The sense of occupying different spaces and in-betweenness that Dima mentioned also resonates with a recent revisit of Wong’s film texts by a group of artists in Australia through an online stage performance ‘In the Mood: A love letter to Wong Kar-Wai & Hong Kong’ which weaves together the themes of cultural heritage and ‘ancestral homeland’ and the sense of longing and intimacy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Affective fandom can stretch across times and spaces, as Dima mentioned in terms of the visit to Fairouz’s home by French President Macron after the port explosion in Beirut. In recent years, I have also delved into the subject of auteur, cinephile and fan pilgrimage which centers on the idea of affective engagements and socio-cultural implications of specific star-auteurs over time. The cross-over subjects of fans, stars and public memory is fascinating, particularly in the era where the past can be collectively retold and reshaped much easier than before.

Camilo Diaz Pino

Thank you Wikanda and Dima for this glimpse into your work and the overall areas of investigation you have been delving into! I’m struck by the many continuities and parallels our perspectives share across the sites we’ve been looking at. Most of all, I’m interested in talking about the ways in which the particular “objects” of fandom mentioned have been contested and/or mobilized within the wider movements, conflicts, and cultural contexts we’ve been looking into. Dima, as the investigation you cover focusses in particular on the work and public presence of a singular artist/persona, I was wondering if you could speak a little more into how Fairouz’s fandom has been negotiated by the political/cultural actors you’ve been looking at? That is to say, given her quotidian pervasiveness, how exactly are different agendas and groups ‘claiming’ Fairuz and her work as their own? Similarly, What rhetorical angles and justifications are given for their claims over her? Do you see some groups as having more of a legitimate claim than others? I ask these questions because I find your description of Fairouz’s impact in the Lebanese and wider Arab diaspora’s cultural/political landscape fascinating for the ways in which it appears to be significant cultural object of political/discursive identification and consolidation, and yet similarly “up for grabs” as it were by virtue of her widespread adoration and quotidianity. I am compelled to think in your description about the ways in which, during the 1970s, 80s and Early 90s, Latin American dissidents were suddenly turned into a transnational diaspora by the wave of CIA-backed dictatorships that overtook the region. During this time, the work of exiled, assassinated, and otherwise censored popular and folk music artists such as Mercedes Sosa (Fig. 1), Inti-Illimani, Victor Jara (Fig. 2) and Silvio Rodriguez were shared as common currency by dissident diasporic communities from Argentina, Chile, Peru, and Uruguay, among others. Even with the return of formal democracy to much of the region in the 1980s and 90s, love of these artists’ carries with it a distinct political fingerprint that cannot so easily be claimed by those not visibly affiliated with Latin American leftist circles. This is true to such an extent that even covering or collaborating with these artists demarcates affiliations that are just as much political as cultural (see for instance Shakira’s duet with Mercedes Sosa, covering a song by Silvio Rodriguez in 2008: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TxzPPQvHIZo). Given this situation in Latin America, I’m fascinated by the very different, but related scenario you describe, and the relative polysemy you identify with respect to Fairouz.

Fig. 1: “Google Doodle” paying homage to Mercedes Sosa, 31 January 2019

Fig. 2: Homage to Victor Jara in leftist Chilean Street art

Wikanda, thank you for speaking to such distinct and concrete points of affinity with regard to our research agendas and the objects, behaviors and movements we are looking at! I’m particularly interested in the ways in which you describe how these cultural objects/commodities from Japan and Korea have become aspects of everyday popular culture in Thailand, as well as how they have been so pointedly mobilized as aspects of locally-oriented activism. I wonder to what extent the negotiations and friction (to borrow the term as conceptualized by Anna Tsing) involved in such flows and processes of transculturation are affected by notions of cultural proximity and history. With regard to the Latin American context for instance, part of what I’ve been trying to highlight in my own work is the growth of an increasingly multi-polar transnational media landscape in the region. While certainly still existing within the parameters of a global neoliberal system predominated by Anglo-American actors, the interaction of media vendors and distributors who operate at a “secondary” level in the global media market has made it so that Latin America has in the lat 30 or so years experienced an explosive level of cultural exchange, interaction and hybridity with regard to the flow of cultural commodities and their integration into local popular imaginaries. By this point I would indeed argue that Latin America’s quotidian media landscape is far more cosmopolitan than that of the still relatively insular and largely “self-sustained” Anglo-American cultural landscape. To reiterate and recontextualize Hamid Dabashi’s eloquent observations with regard to the effects of colonialism on the wider world, subjects in the colonized world

[...] grew up compelled to learn the language and culture of our colonial interlocutors. These interlocutors have never had any reason to reciprocate. They had become provincial in their assumptions of universality. We had become universal under the colonial duress that had sought to provincialise us. (Dabashi, “Fuck You Žižek!”, https://artafricamagazine.org/fuck-you-zizek/).

It is with these asymmetric relationships in mind – those that allow and oblige the margins to be well aware of the center while the center can choose to ignore the margins – that quotidian meaning-making becomes so important to take into account when attempting to grapple with how neoliberal globalization has both cemented and exploded these dynamics. The question that I keep coming back to however is what supposed margins (and aspiring “centers”) make of each other when compelled (for whatever reason) to interact amongst themselves?

I’m curious to what extent comparable levels of cultural interaction, hybridity and syncretism are at play in Thai experiences with the media imports you mention. Because while I imagine Thailand must surely share many continuities with other South-East Asian states with regard to the influence of Japanese, Korean and Chinese actors, it has also undergone an entirely unique history with the European colonial project and its continuities in the contemporary global landscape. As such, there is probably much to be said about how processes and effects of media globalization have manifested there.

References

Sosa M, and Shakira, “La Maza” Concierto ALAS, 16 September 2008 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TxzPPQvHIZo

Dabashi H. “Fuck You Žižek!” Art Africa

https://artafricamagazine.org/fuck-you-zizek/

Dima Issa

Round 2

Camilo and Wikanda, I really enjoyed reading both of your statements, they open a number of trajectories that tackle fandom identity and positioning amidst ‘glocalised’ dynamics.

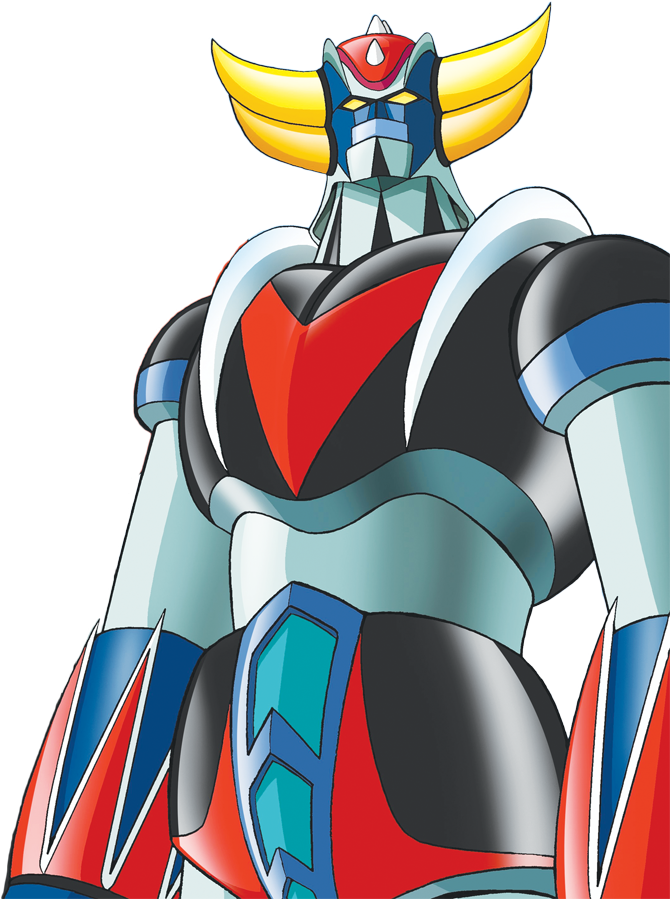

Camilo, your research on Japanese cartoon media flows is so relevant especially with the increasing diversity of media content that is shifting from ‘Western’ dominance, or media imperialism. Your discussion on Dragonball 2 in context with a collective political agenda reminded me of the use of the animated show Grendizer[1] (an anime character popular in the 1980s and 1990s) to narrate the struggles of the Syrian war[2], further research on this has been done by Omar Ghazzi, who looks at the shows as a form of ‘nostalgic defiance’[3].

Grendizer

This appropriation of anime to tackle and understand events that deviate from the banality of the quotidian, such as times of war and violence, but at the same time, the way these texts have ‘integrated into Chile’s popular imagery’ and the way they ‘comingle and coexist’ provides an almost paradoxical dichotomy that showcases the ways in which fandom allows for a sense of comforting normalcy. These ‘intimate’ understandings of texts are essentially affective, drawing on individual and collective interpretations that are intergenerational.

Your discussion on K-pop really struck a chord with me (no pun intended). I have been lecturing in Lebanon for almost ten years now and the number of students who are obsessed with K-pop is increasing exponentially. It was mostly evident in my race, gender and sexuality class, where students looked at K-pop as a lens through which to explore and understand sexuality. The presence of these transnational groups provides for a different understanding of sexuality that moves beyond Western perspectives and allows for a less invasive and polarizing definition of sexuality that students from younger generations can identify with.

Just to quickly answer your questions Camilo, with regards to Fairouz and her music, this negotiation of meaning is very dependent on the political groups that listen to her. Through her music and her sheltered persona, Fairouz is able to straddle multiple political and cultural identities, because she has not affiliated herself to just one ideology. Her stance on Palestine is a key constituent and places her at the helm of understanding ‘Arabness’, but even then she never explicitly mentions the Palestinians by name, so her listeners are able to interpret her songs freely. As a ‘figure’, Fairouz takes on multiple meanings. There is a fluidity to her songs, which allows for a relationship with various vantage points. It is also interesting that you mention Shakira, because I discussed her in my PhD thesis. There is an article by Maria Elena Cepeda, who talks about Shakira as a ‘transnational citizen’ who exudes ‘Latinadad’, allowing for South American diasporic audiences to connect with her. It is significant to note that while Shakira is half Lebanese, she is not seen as an ‘Arab’ singer. Obviously, this may be for many reasons, from generational to ideological, but it brings to the forefront this notion of identification and representation in forms of fandom that are founded in culture and beliefs.

Screengrab of Shakira from her halftime show (via https://www.arabamerica.com/shakira-personifies-a-multicultural-identity-in-a-globalized-world)

Wikanda you have given such wonderful insight into different types of research going on in Thailand. I especially loved your explanation on the terminology used among fans, creating this sense of ‘solidarity’ among them. I also found the definition of ‘mae-yok’ extremely interesting in terms of gender politics and the way music fandom translates according to culture. Initially, I thought you were talking about what the Western world would call ‘groupies’, but the maternal and nurturing attributes assigned to the term highlights this shift in understanding forms of fandom that move away from the sexual implications associated with ‘groupies’. The ways in which ‘mae-yok’ are depicted as supportive and cognizant of talents is almost selfless. It is also interesting to see how fandom is linked to ‘youth democratization and regional solidarity’ and the utilization of the ‘#milkteaalliance’ hashtag to draw supporters. I found that not only fascinating, but incredibly witty of the youth who organized and put that together. It also brings to surface notions of inclusivity versus exclusivity in fandom, especially with the involvement of politics. In Lebanon, music played a huge role during the October 17 uprisings and the soundscapes heard across the country. This was significant on a number of levels. Firstly, older music by more classical artists were sampled, mashed up and juxtaposed by activists on social media platforms and by DJs on the streets during the protests. These were younger perspectives on notions of identity that at times deviated from those of older generations. The biggest example is when the local Lebanese death metal band Kimarea covered a famous Lebanese song by Majida Al Roumi, ‘Beirut Set El Donya’[4], (written by Nizar Qabbani), causing controversy among Al Roumi’s management and fans who were appalled by what they labeled a ‘blasphemous’ take on the song with its ‘death metal fundamentals’. These sonic disputes highlight themes revolving around nationhood and its representations among different generations of fans. Secondly, the soundscapes during the uprisings were also contested, further showcasing the lack of ‘unity’ among the protesters. As a country divided on so many religious, political and ideological fronts, Lebanon is unable to unite under a common narrative and the way that this is evident, is by exploring the ways in which various forms of fandom intersect, collide and oppose each other.

Death metal band Kimeara featuring Cheryl Khairallah performing “Ya Beirut”

[1] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ibaeQieYFdo

[2] https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-36884058

[3] Al-Ghazzi, O. (2018). Grendizer leaves for Sweden: Japanese anime nostalgia on Syrian social media. Middle East Journal of Culture and Communication, 11(1), 52-71.

[4] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bc2OmHp5V9U

Gk