My Favorite Discoveries in 2021 Among Older Films

/Altogether, I viewed 228 feature films and shorts in 2021 from 2019 or earlier. Almost all of these were watched online. Most of these choices were part of programatic deep dives or film festival experiences, so rather than offering a ranking, I thought I would describe some of my excursions into film history this past year.

50s Science Fiction — I began the year with a yen to watch as many creature features as I could find, a yen fed by several box sets I had gotten for Christmas, which led me to ordering more boxed sets, and finally starting with a year by year listing of 50s science fiction films, seeing how many of them I could find and watch online — mostly through YouTube. I did not get past 1952, so this is a project I hope to continue into the coming year. My fascination was with stories of catastrophe and the different mechanisms by which the filmmakers imagined the society responded to large-scale threat, issues which spoke powerfully to the present moment. And since the world rarely actually ends in these films, these films ultimately provide reassurance and resolution. Some of what I saw were classics that I had seen through the years, but I saw new things watching them in conversation with lesser known titles. But here are some of the discoveries I made — mostly deep cuts from the era that time has forgotten, perhaps unfairly. Most of these are more interesting films than great films, but then I wasn’t looking for cinematic masterpieces. The 27th Day (1957) is one of several films I watched which emphasis global responses — an alien extracts five ordinary people, each from a different global power, and provides them each with weapons that can destroy the planet, leaving them with the choice of whether humanity deserves to survive. It’s a metaphor for mutually assured destruction, released at the height of the Cold War. 12 to the Moon (1960) gives us a multinational space mission, representing astronauts from the super powers and from a range of developing nations. It anticipates the diversity on the bridge of the U.S.S. Enterprise on Star Trek and the multinationalism of the recent Away television series. Of course, the characters are all stereotypes but it’s fascinating to see how national and gender stereotypes are played against each other here. The Invisible Boy (1957) uses Robbie the Robot, first introduced in Fantastic Planet, to tell a story of a scientist father and his precocious young son confronting a cosmic crisis, as robots threaten to rule over humanity and Robbie, who has befriended the boy, has to decide which side he’s on.

Film Comedy — I returned to teaching American film comedy for the first time in more than twenty years, which led to me watching as many films in preparation before the fall seamster started. So many titles have come out on DVD, especially comedy shorts from the silent period, and many films you would have had to track down in archives are now flowing freely on YouTube. I went back through the classic four silent performers, Chaplin, Keaton, Lloyd, and Langdon, seeing. many of the later two comics films for the first time. I finally really grappled with the alienness of Langdon’s approach to slapstick and found myself drawn to the films he made after he parted ways with Capra. I realized that my reading Name Above the Title, Capra’s memoir, when I was a teen, had biased my perceptions, but I was especially drawn to The Chaser (1928) where the alienness of Langdon’s persona is coupled with play with gender identity: a judge sentences Harry to wear a dress and do the housework. My students found this a fascinating study in gender fluidity, far more ambiguous than most of the anti-suffrage films I have seen, about women ruling over men. The inter titles in particular seem to play with the concepts of masculinity and femininity in fascinating ways. My consumption of silent comedy led me back to Sidewalk Stories (1989), a film I had taught several decades before, and so it constitutes a rediscovery. Charles Lane, a Black filmmaker, revisits Chaplin’s world — especially The Kid — for a more contemporary representation of homelessness and the way society perceives and treats its “tramps.” It is funny and touching in equal measures and remarkably well done for a first feature made as a student film at NYU. I have long wanted to check out the Crazy Gang — a music hall troop who was the British counterparts of the Marx Brothers. I was delighted to find several of their films online, and was particularly taken by A Ok For Sound, (1937) which has been the most meta of their works I have seen so far. I would describe it as falling somewhere between Night at the Opera and Hellzapoppin, perhaps not as good as the later but in the same ball park. I also worked my way through the surviving feature films of Raymond Griffith, the comedies of Douglas Fairbanks, and as the year draws on a close, the films of Frank Tashlin. Throughout, I was left really admiring what I saw of Hal Roach’s productions and really eager to see more.

Film Festivals — I was able to attend four online film festivals this year, each dedicated to historical films, but with different biases: Bologna, Pordonone, Turner Classic Movies, and Los Angeles Cinecon. I have attended all four in person and missed the range of titles normally offered, not to mention the conversations around the films, and we missed altogether the San Francisco Silent Film festival which has been one of my annual highlights. The highlights of Bologna were Belphegor (,1927) a four part French serial (each part lasting more than an hour) involving a shadowy figure lurking in the Louvre and a crack detective trying to identify the culprit. It is full of the stuff of the pulp imagination of the era. I was also taken by two noir films they featured (the original Nightmare Alley (1947) and I Wake Up Screaming (1941), which has left me hoping to watch more noir in 2022. Pordone brought me Phil-For-Short (1919) a silent film about an independent spirt who today we might call nonbinary, which introduced me to the charming silent screen actress Evelyn Greely. My favorites from TCM were two titles that dealt with threats to democracy — Black Legion (1937), in which Humphrey Bogart joins a white supremicist organization, and The Mortal Storm (1940), which depicts the rise of Nazism from the perspective of a free-thinking academic family centered around James Stewart. I had seen both before, but they spoke to the current moment with particular poignancy. And the joy of Cinecon is its profoundly anti-canonical impulses. I have been enjoyed being introduced to the films of Judy Canova, a broad physical comedian who crossed over to the screen from radio and recoding, with a hillbilly twang to her singing and a wonderful personality. This year, they showed Sleepy-Time Gal (1942) which is my favorite of the films I have seen with her so far. There was so much more that interested me at each of these events and I hope these festivals continue to provide online offerings for those of us who can not be there in person.

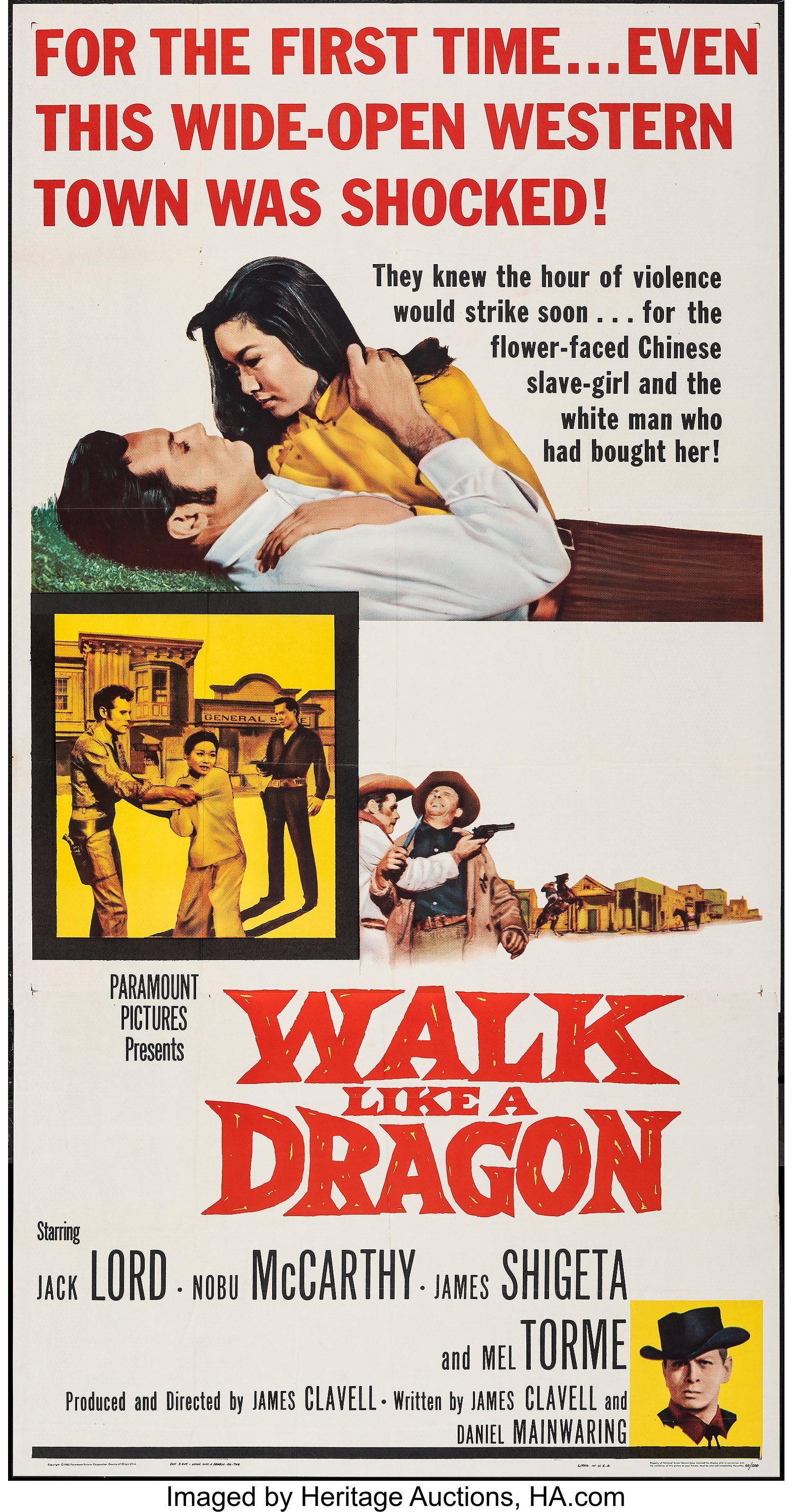

Some other highlights: My current research interest in post-war children’s media gave me a chance to watch A Boy Ten Feet Tall/Sammy Goes South, Alexander MacKendrick’s 1963 saga of a white boy who wanders across Africa alone in the midst of the Suez Crisis. It is full of haunting images and a great supporting performance by Edgar G. Robinson and led me to watch Spielberg’s Empire of the Sun, (1987) again, upon which its influence can be strongly felt. I participated in an online conference about 50s and 60s American westerns and a fascinating presentation led me to check out Walk Like A Dragon (1960), one of the few American westerns of the period to deal sympathetically and in depth with the experiences of Chinese-Americans. Its treatment of a cross-racial romance may be problematic in our time, but was progressive in its own, and sufficiently complex to keep one scratching one’s head throughout.