Global Fandom Jamboree Conversation Series: Hadas Gur-Ze’ev (Israel) and Miranda Ruth Larsen (Japan) (Part Two)

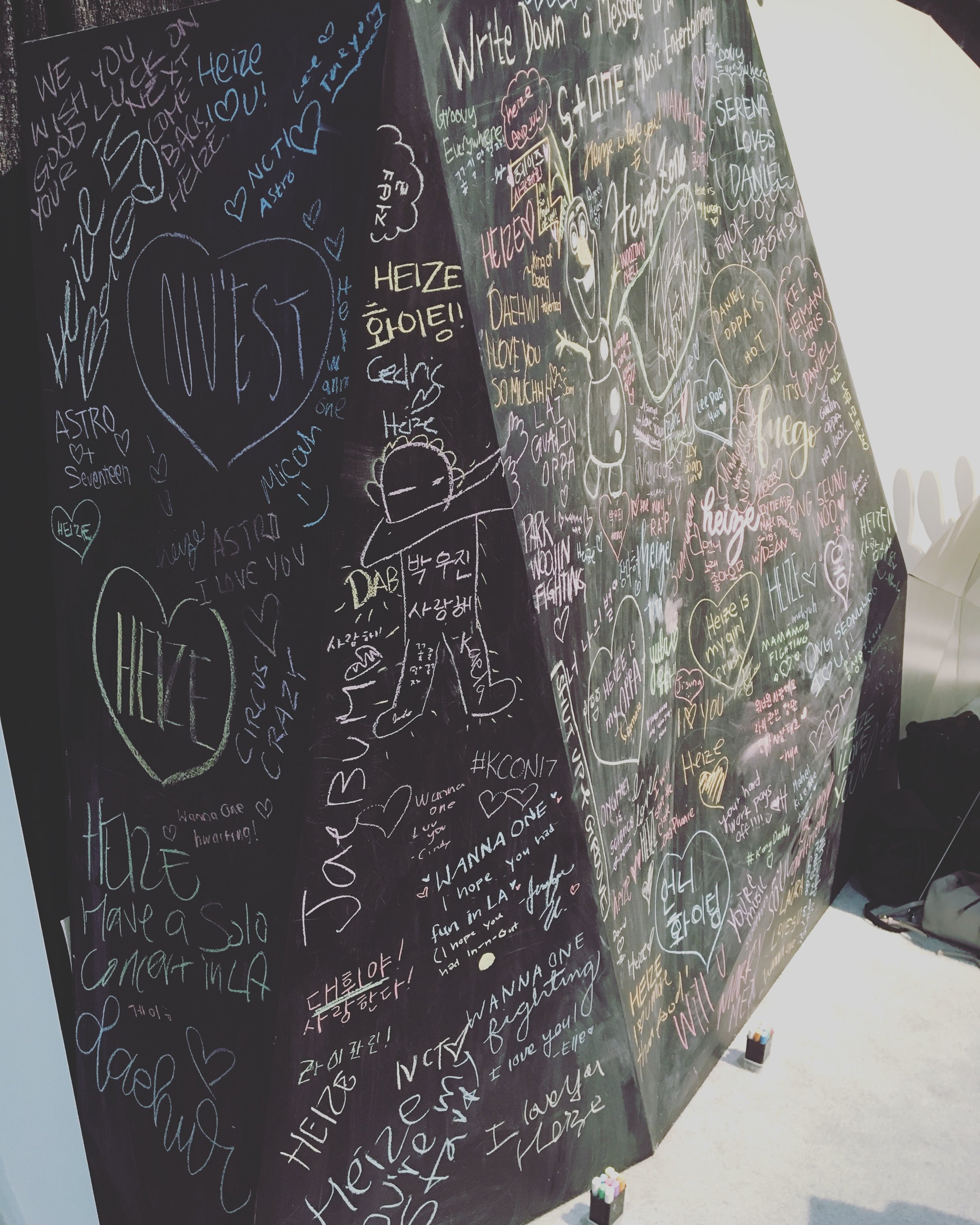

/Fans write messages to K-pop artists performing at KCON LA 2017. (Author's photo, 2017)

Miranda Ruth Larsen: Many thanks for your participation as well, Hadas. I absolutely agree with your point that physical distance is as vital as symbolic distance, and that the realities of fandom are better illustrated with a rich understanding of particular contexts.

As to your question about K-pop fans in Tokyo versus Los Angeles – my response would be that while someone in each locale may be a fan of the same idol group, it is imperative to recognize differences in access, proximity, and so forth. Everything should, in an ideal mode of both academic and fannish engagement, be viewed as interconnected but localized. In other words, only certain statements should fit the bill of “global K-pop fandom,” and even the monikers “Japanese K-pop fans” or “Anglophone K-pop fans” must be broken down further for an accurate representation of how these fans are fans. In doing so, we can do as you suggested – have open conversations about the plasticity of boundaries and the fact those boundaries are often more like a disorganized Russian nesting doll.

I think your study of The Geekery offers an excellent point of analysis, beginning with its platform structure via Facebook. I’m interested in the types of posts shared there, particularly if you’ve noticed patterns as to certain fans taking on defined roles. In many bounded communities, established BNFs might rise to prominence because they always share the latest news, post the most photos, have the most incendiary discussions, and so on. Do you see this on The Geekery? Are Israeli comic fans claiming niche brands for themselves within this community, and do those niches point to the struggles of marginalized members?

I believe that your experiences with The Geekery can also speak well to COVID-19, given that online connection has become a central point of engagement for many fans during the pandemic. In my research, co-presence is not necessarily physical presence; in fact, co-presence is difficult to accurately measure because it forays into the realm of affect. What’s important is the opportunity for that affect. For most fans – but not all – this points to the physical, but there are other means to connect, depending on the context.

Your final question is a tricky one, as it widens out our discussion to transcultural fandom as a whole! Of course the factors of physical location, country of origin, and culture impact ability to take part in global fandom. So do practical factors like internet speed, disposable income, and proximity to a well-stocked library. Wholly acknowledging these factors is a vital framework that must be integrated with every fan studies engagement. Without them, we run the risk of making romanticized generalizations and commit a disservice towards other academics, fans, and students.

ICon 2017

Hadas Gur-Ze’ev: I think we both agree and recognize the plasticity of boundaries that constitute and define fan identity (or opportunities to participate in fandom). With this in mind, we can also ask about the particular power-struggles that shape the boundaries and the biases they hold—ones that stem from practical factors like distance or socio-economic status, but also symbolic struggles over resources and authority between different fans. This will require to look not only at broader interconnections within global fandom, but also how these struggles respond to changing contexts and trends in global popular culture (e.g. representations of gender, race, minority groups and inequality in general).

Responding to your questions, the platform of Facebook is indeed an interesting space for negotiations around fan identity construction—where participants’ posts often serve, consciously or unconsciously, to define self /in-group identity as a “true” fans. While some users are more active than others (as you would expect on digital platforms), I wouldn’t say it is certain (individual) fans taking on defined roles—but rather a certain type of fans that showcase their prominence by the use and control of the “correct” insider-knowledge. These, as I see it, are again questions of boundaries—and a conflict including specifically gendered aspects (that are both local and global in nature). While some attempt to protect rather limited boundaries and reinforce (masculine) canon, other voices in the group attempt to incorporate new perspectives and audiences, presenting female/feminist voices as equally “authentic”.

In my study of The Geekery I focused on the struggles of marginalized members based on gender, which is especially crucial in the case of the identity-label “geek” (for its previously perceived masculine hegemony). In this group, claiming ownership/knowledge of “correct” (canonic) niche brands translates into “fan-credit” and helps ensure the exclusivity of those already in power position. Yet, in the current cultural moment we may be witnessing a battle for these positions of power, and a sort of “opening-up” of fandom for more diverse audiences.

Asking ourselves about the factors (and biases) that impact the ability to take part in a global fandom, should we be able to recognize common dominant struggles for representation or participation? And if we do see some former-marginalized members reclaiming a position of power, who are the others at the (new) margins whose voices we might be missing, both at the local and global levels?

Fans watch requested videos in a K-pop cafe in Shin-Ōkubo, Tokyo. (Author's photo, 2016)

Miranda Ruth Larsen: I believe this has been a fruitful exchange; as I’ve expressed to Hadas, I’m quite sure we could continue indefinitely given the fascinating touchpoints between our two perspectives and areas of fan research.

My initial entry for this project was, admittedly, more of a manifesto concerning fandom and fan studies as a field. Throughout our exchanges, Hadas and I have drawn on our research in geographically and linguistically demarcated fan spaces. In doing so, we have both pointed to the vital importance of context and recognized that even those contexts carry limitations; whether it be the platform boundaries of Facebook or the winding streets of Shin-Ōkubo, these settings both inspire networks and bring access into question.

Moving forward, I hope that more fan studies work recognizes the affectively messy, experiential, nuanced, and unequal operations of fans and fandoms. We cannot ignore that fandoms take place under capitalism, that affect drives both collaboration and division, that ‘fans’ as a label often glosses over crucial markers such as race, gender, sexuality, socioeconomic status, age, and so on. Additionally, the digital platforms and physical spaces where fandoms happen are subject to numerous influences.

The observations Hadas and I have raised in our discussion are proof that fandom contexts provide challenges even to a well-informed researcher. The next step – getting our work ‘out there’ – also offers distinct challenges. I would like to conclude by stating that recognizing ourselves in our research remains a divisive topic in fan studies. Academic climates, like fandoms, are also nuanced (nuanced, here, is an attempt at diplomacy). In some circles, identifying oneself or one’s work as fan studies is actively discouraged. I hope that the aca-fan position becomes more accessible and acceptable given the current nature of the world falling apart. As COVID-19 continues to deepen concepts like access, borders, and cultural flows, diverse and outspoken aca-fans are needed to make sense of how and why people connect with media and each other.

Hadas Gur-Ze’ev: This has been a great conversation! We could definitely continue our discussion infinitely, seeing that context and limitations are always relevant and constantly changing. In a way, I think both our perspectives posed questions about the centers and peripheries in fandom; perhaps our exchange can shed light on the common/specific biases for different fan spaces, each with its own center and periphery.

I find these questions particularly interesting at this cultural moment, where struggles of access in fandom can be seen through the lenses of globalization, capitalism, a global pandemic, or worldwide influential movements for more equal opportunities (#MeToo/BLM?). In this broader context, we might even consider our conversations as part of a whole set of new perspectives that are claiming more dominance at the center/mainstream of fandom (and possibly fan studies?)—ethnicities, genders, sexualities, disabilities, minority groups, and diverse identities.

I thank you again for the opportunity to think more about our shared areas of research, and can’t wait to see where else this is going in the future (for fans, aca-fans, and global culture as a whole)!