Jack Benny and American Radio Comedy: An Interview with Kathy Fuller-Seeley (Part One)

/When I was in middle school, there was for a brief time an amazing radio station in Atlanta that was totally programmed with classic radio comedy and drama, which sent me down a rabbit hole trying to learn everything I could about old time radio. Ever since, I have been a fan. Witness my earlier post celebrating the wonders of the Columbia Radio Workshop and my discovery of the OTRCAT website where you could find full runs of vintage series at 5 bucks a disc, This past year, I have fallen down that rabbit hole again because of the number of shows that can be found on podcasts. Somehow vintage Dragnet, Lux Theater, Damon Runyon Theater, and Jack Benny show, among others, have put me to sleep during the pandemic, My interest in Jack Benny goes back to middle school but has taken on renewed interest since I moved to the Eastern Columbia Building in Downtown LA, just a few doors down from the May Company where Jack met his future wife, Mary Livingstone, and the home of a department store which many fans believe is where Jack went Christmas Shopping in a famous episode of the series.

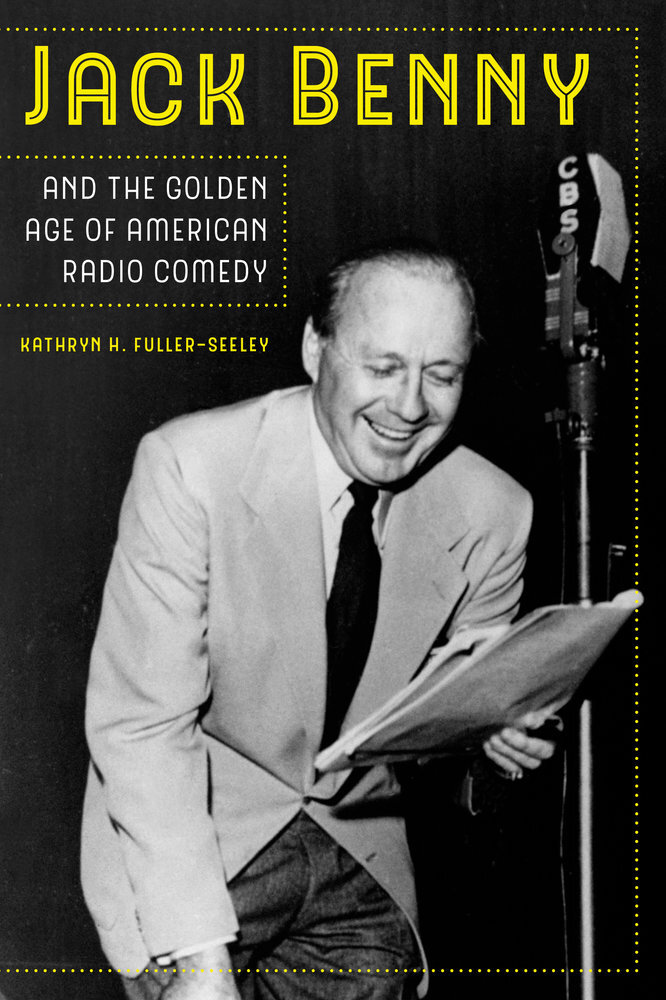

For Christmas this year, among other things, my wife gave me a copy of Kathryn H. Fuller-Seeley’s Jack Benny and the Golden Age of American Radio Comedy, a wonderful book which provides the historical context I needed to listen to the great Jack Benny and Fred Allen episodes with a new level of appreciation. She offers so many different frames for understanding the historical importance of the program in terms of its place in the evolution of radio comedy, in historical representations of race and gender, in terms of cross-overs between radio shows and in terms of the comedian’s relationship with his sponsors, all important insights into American cultural history and in terms of what they teach us about the evolution of American radio. Because of my great love of this book, I reached out to its author, who is an old friend, and asked if she would agree to be interviewed. She has shared some rich tidbits from the book here, but if the is of interest, you will want to read the whole book.

Classic radio comedy and drama has been a neglected topic in media studies for a long time but we are starting to see more scholarship in this space, including your book. What factors are contributing to greater scholarly interest in these vintage radio programs?

That’s a great question, Henry, and I have a shorter answer, or a longer one that could become a 30-page lit review, haha. My views might be quite idiosyncratic, as I was trained in a history PhD program in the late 1980s, versus a media studies program, and of course I have opinions that might differ from others!

My work stands, of course, on the shoulders of giants. Within media studies, the formative books in the US radio history field have come from Michele Hilmes and Susan Douglas, (the former first investigating the ways Hollywood interacted with radio, the latter coming from a technological history background to chart the formation of early radio broadcasting). Erik Barnouw published his epic trilogy on broadcasting history in 1966-70.

The only claim I might make is that my book is the first academic book to take a sustained look at Jack Benny’s radio career. I learned so much about him from Hilmes, Douglas and Barnouw. Because of their examples and their mentorship, there is now a vibrant field of radio history and radio/audio-media studies. Increasing interest in historical and contemporary comedy and humor studies, in media studies and American Studies, is also encouraging scholars to study outstanding performers of the past.

Why nobody had tackled the topic of Jack Benny before was a mystery to me, but perhaps it was due to commercial network radio being even more of a “bad object” to US media scholars than television. (The British could at least be proud of the BBC). Jack Benny was US radio’s most iconic performer, so perhaps he shouldered that burden of not being worthy of discussion. Radio’s ephemeral nature, existing only as audio, and broadcast live by the networks back in its “golden age,” meant that many media scholars, drawn to the visuality of film, overlooked radio.

US radio seemed (to most critics) completely compromised by corporate control. The dominance of two networks, the “sameness” of top-rated radio programs (dominated by a small handful of comedians and singers from 1932-1955), the overwhelming prevalence of commercial concerns through advertising and the control of programming by advertising agencies and sponsors, all kept scholars away. The paucity of substantial critical radio criticism until after 1946 (when John Crosby, Jack Gould and others) did not help. And the lack of extensive official collections of recordings and contextual documents (apart from the amazing NBC collection at the Wisconsin Historical Society) make studying US radio history a huge challenge.

However, there has long been a parallel stream of US radio history research that comes from US history, American Studies and history of technology, areas that have studied radio broadcasting as a major mid-20thcentury cultural and political force. (topics include FDR’s fireside chats, the propaganda of Father Coughlin and Huey Long, ethnic radio in Chicago, Amos ‘n Andy, Fred Allen, radio’s role in World War II,etc.) Historians are often immersed in paper archives, so a lack of actual broadcast recordings did not totally deter them, as they delved into scripts, corporate, government or personal archives and technical documents.

Fans and collectors of what became known as “Old Time Radio” also played a significant role in enabling the study of radio history. As Nora Patterson’s research shows, it was the work of fans from the 1930s to the 1970s (continuing today with the wonderful International Jack Benny Club and other organizations and individuals) diving into dumpsters to retrieve transcription discs, creating and sharing taped versions of old shows, that created program archives. Old radio shows, broadcast live, were almost never “re-run,” and recordings of programs were not officially kept by the networks or sponsors, or often even the performers. Fans over the years assembled checklists of programs, located rare recordings of rehearsals and repeat performances for the West Coast, and through their passion for the old shows, made a substantial chunk of old radio accessible to listeners today (and now programs are increasingly available in digital format). I was fortunate when studying Jack Benny’s radio program (encompassing over 900 episodes across 23 years) that about 700 recordings have been assembled by fans. My other contribution to Jack Benny research has been to labor to make the other approximately 240 episodes for which there are no recordings (Benny’s early formative years 1932-1935) available published in script form, dug up from the Benny papers at UCLA. The scripts are fascinating to read. See Jack Benny's Lost Radio Broadcasts, Volume One: May 2 - July 27, 1932 (by Jack Benny and Harry Conn, edited and with introduction by Kathy Fuller-Seeley) Bear Manor, 2020.

If you want a brief bibliography of some of my favorite classic US radio history books, it would include, these, plus others I have mentioned in subsequent responses….

Hilmes, Michele. Radio voices: American broadcasting, 1922-1952.

Hilmes, Michele. Hollywood and Broadcasting

Douglas, Susan. Listening In: Radio and the American Imagination

Douglas, Susan, Inventing American Broadcasting

Barnouw, Erik. A History of Broadcasting in the United States: 1. A Tower of Babel: to 1933. Vol. 1.

Barnouw, Erik. A history of broadcasting in the United States: Volume 2: The golden web: 1933 to 1953.

Barnouw, Erik. The Image Empire: A History of Broadcasting in the United States, Volume III--from 1953.

Havig, Alan. Fred Allen's radio comedy.

Ely, Melvin. The Adventures of Amos n Andy

Cohen, Lizabeth,. Making a New Deal: Industrial Workers in Chicago

Wertheim, Arthur Frank. Radio comedy.

Horten, Gerd. Radio goes to war: The cultural politics of propaganda during World War II.

Brinkley, Alan. Voices of Protest: Huey Long, Father Coughlin, & the Great Depression.

Lenthall, Bruce. Radio's America: The Great Depression and the Rise of Modern Mass Culture.

I am of course very interested in the transition which Jack Benny makes from vaudeville to radio. What are some aspects of vaudeville that stay with him and what needs to be shed as he makes those adjustments?

In the book I talk about Jack’s earliest episodes of his radio program in May 1932, and it seemed to me that, at that moment, he had not really thought through how radio was going to be different from vaudeville. Jack had been on the vaudeville stage since age 16, as he moved around the small time Midwestern circuits being a violinist who interjected a bit of musical humorous byplay into his performances (first with a partner, but after World War I as a single). He learned how to perform comedy lines during his time in the Navy, participating in a variety show for charity. By 1920, he played the violin less and began talking more. In the mid-1920s he rose from regional circuits to top national vaudeville houses. Benny began to model his routines on those of the newer “suave” comics like Frank Fay, who wore fine evening dress and spoke directly and informally to the audience, telling tales and stand-up jokes (and in Fay’s case, slaying any hecklers in the audience).

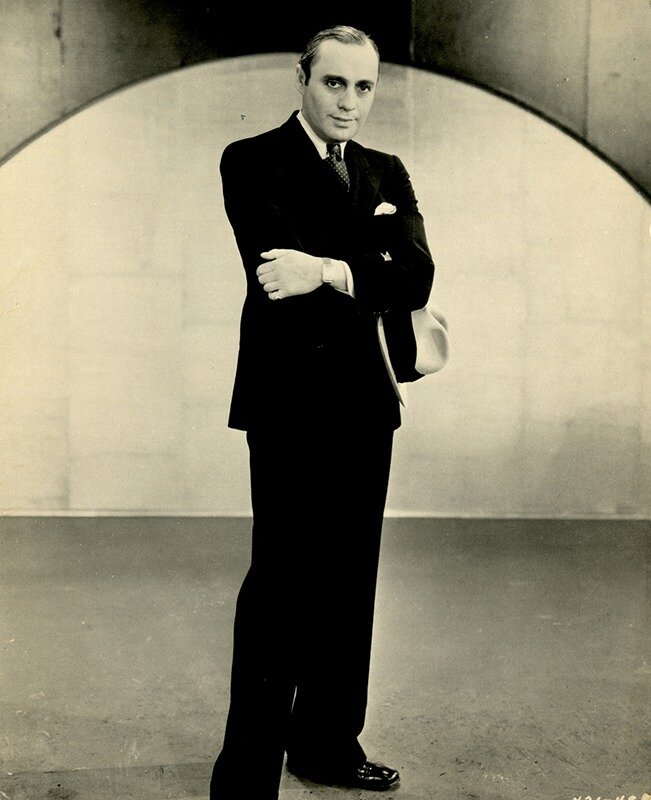

Frank Faye

Jack Benny followed Fay’s career path to become a prominent (albeit much better-liked) “master of ceremonies” at the legendary Palace in New York and in top vaudeville theaters across the US. Benny now was a genial “Broadway Romeo,” a middle-class white Midwesterner with almost no references to ethnicity in his jokes or tone of voice, well-dressed, mild-mannered, but still the fellow for whom things always go wrong. As “MC” Benny interacted with the other acts he introduced, and he told his stories standing at the front of the stage.

That was the character Jack Benny brought to radio. What he had NOT counted upon was how much new material radio demanded at each performance. No longer would one well-crafted 17-minute monologue last an entire year as Benny traversed the country from week to week across the vaudeville circuit. His material was eaten up in a single performance, broadcast to a national audience. For the Canada Dry radio show, Benny needed to provide about 15 minutes of comic patter between the songs played by George Olsen’s band and sung by former Ziegfeld Follies chanteuse Ethel Shutta (Olsen’s wife). I write in my book that Benny, panicking after his fourth bi-weekly radio appearances, had run through all his best material. Benny had always been dependent in vaudeville on comedy writers to help provide him material that he would then personalize and hone. Now he hired a full-time writer, former vaudevillian Harry Conn, and the two of them started crafting a kind of comedy that moved away from Benny simply performing monologues, and brought in the best of his Palace Theater-like exchanges with the other program members. As the band and singer remained the same each week, Benny and Conn crafted radio personas for them too, and Jack interacted with them in increasing amounts of dialogue. Then Benny and Conn began to interweave skits and film parodies and visiting guests, and began to turn the show into what was something like a workplace situation comedy. Only the upheaval of changing to new sponsors and casts four different times kept that format from becoming more ingrained into the program until 1934.

Henry’s question had been about Jack Benny’s vaudeville routine. If we were only to look at Benny’s radio career, we would think that he left his vaudeville format behind in 1932. However, all throughout this period Jack continued to appear as MC and performer at vaudeville-like stage shows at the biggest picture palaces across the land, and at state fairs or other major events.

During World War II he took his stage shows to military camps in the US and overseas with the USO. When Benny finally capitulated in October 1950 to travel to New York to perform a live television program, he reverted back to appearing before a small studio audience, standing on stage before a curtain. In a way, Benny returned to his vaudeville MC roots for television, mixing talk in front of a seated audience with staged skits involving guest stars and his radio regulars. As Benny’s television program in the 1950s and 1960s became more structured like a situation comedy, he took his vaudeville format to Las Vegas and successfully performed there into the 1970s. Vaudeville monologues never really ended for Jack Benny, they just moved to other places.

Jack Benny’s program lasted for several decades on radio and then on television. What are some of the ways that they were able to keep this program fresh for audiences over a duration that would be unheard of in contemporary television (with perhaps the exceptions of Saturday Night Live or The Simpsons).

The reasons for Jack Benny’s longevity in show business are many. One is character – Benny’s own comedy persona, a likeable everyman, and a person listeners and viewers could both relate to and feel superior to – he’s the eternal loser, a classic schlemiel in Yiddish comedy. The other comic characters he surrounded himself with were memorable, a group of quirky friends, each with flaws, but an ability to get along with the rest.

Another is the large collection of staple comedy bits -- Benny’s writers created a large number of comic routines, scenes and interactions that could be endlessly recycled (comfortable familiarity) but also slightly twisted or tweaked each time to make it seem new or refreshed. Benny and his writers were wise to never lean too hard on any one character or routine, so that the audience might tire of them from repetition. A character could not have a major role for weeks, and then when the character returned, it was like they had never left. Superb writing and terrific comic performances played a role.

The pseudo-situation comedy format that Benny and his writers devised on radio also was especially flexible, and so perhaps listeners did not tire of it as quickly as a more limited program structure. Benny always said he wanted to do many different kinds of shows to provide variety, and a radio episode could be the running of the radio program, another might take place right after the show ended or beforehand during rehearsal. The gang could go off on an adventure together (like a multi-episode trip to Yosemite). The whole episode could take place at Jack’s house involving Rochester and domestic issues. Or a guest star would interact with Jack. Or the cast would perform a parody of a current film. Radio’s ability to take the performers to any location made this much easier (there were not costs to build sets or create costumes). Benny’s television programs by the mid-1950s would often be more limited to his home place, or the TV studio stage from which he gave his opening monologues.

It’s worth mentioning that one reason for Benny’s longevity was that radio sponsors and networks in the 1930s, 40s and 50s were far more willing to continue an existing show that earned adequate ratings/listenership. There was less competition for audiences between rival shows broadcast at the same time, and conservative sponsors were convinced to deepen connections between their star performer and the products they wished to promote. Starting in the 1960s on network television, production became so expensive, and the race to get high ratings was so heated, that programs did not have the luxury of developing over several seasons, and shows were cancelled if they did not immediately become hits.

Kathy Fuller-Seeley is the William P. Hobby Centennial Professor of Media Studies in the Radio-TV-Film Department at the University of Texas at Austin; her research specializations are in US radio, film and TV history. Recent publications include: Jack Benny and the Golden Age of American Radio Comedy (California 2017);“Archaeologies of Fandom: Using Historical Methods to Explore Fan Cultures of the Past,” in The Routledge Companion to Media Fandom (Routledge 2018); and (edited) Jack Benny's Lost Radio Broadcasts, Volume One: May 2 - July 27, 1932 (BearManor 2020).