Global Fandom Jamboree Conversations: Enrique Uribe-Jongbloed (Colombia) and Tchouaffe Olivier (Cameroon) (Part One)

/Conversations on Comics: On Cultural Effraction and the Feedback Loop

by Tchouaffe Olivier (Cameroon)

The things I find remarkable about the comics is how they entered our consciousness by effraction. Indeed, we were not the intended original audience but happened to be an audience by effraction. Many of these comics, such as Blek Le Roc and Lucky Luke, were themselves examples of idiosyncratic cultural borrowing responding to the American’s invasion of films and comics in Europe and are, consequently, themselves derivative of the Hollywood Western and the myth of manifest destiny and the last frontier embedded in the mythology of the west and all the cultural bagages we have now come to recognize. Comics like Tintin, likewise, emanates from a cultural Belgian milieu that was very catholic, reactionary and colonialist.

Indeed, can we completely free Tintin from its anchoring in the past century? The first album "Tintin in the land of the Soviets" was indeed responsible for portraying the worst mistakes of the Soviet Union. The controversies over its racism and colonialism arise when it is a question of republishing "Tintin in the Congo". Finally, how can we fail to notice the absence of a female character with the exception of the Castafiore?

First, the demonstration that what is considered culturally appropriate or politically correct change overtime. Second, without parents, without a past other than his tribulations, without a girlfriend or boyfriend, globally without attachment and without accountability to anyone, without sex and almost without a face: Tintin is an autonomous individual, scientifically skilled with an agency of his own. Thus, it is Tintin’s abstraction that makes up his modernity and legitimacy as an icon of freedom, self-reliance and technological ingenuity that appeal with an audience dealing with a world that is becoming more complex by the days.

Thus, Tintin still seems so alive in the 21st century. Like a character of the present, with a contemporary reading that forgets its anachronism.

What is spectacular, however, it is how these comics have managed to spread all over the world, as a form of subaltern culture, and came back to Hollywood’s mainstream moviemaking.

It is clear that Steven Spielberg who made a movie about Hergé’s Tintin (2011) and realistically followed Herge’s visual genius and erudition with his own visual imagination and performance capture prowess with the ambition to rival with movies such as James Cameron’s Avatar. However, rather than Hollywoodized it, Spielberg keeps the spirit of Tintin to become the first to globalized Tintin in films, rather, that a European filmmaker. Spielberg took a big chance on a comic that was pretty much unknown in the United States.

In addition, Spielberg was also inspired, with Georges Lucas, by Hugo Pratt’s Colto Maltese for Indiana Jones.[1]

Furthermore, as with the Hong Kong Martial Art films, the Samurai movies of Akira Kurosawa and the Western Spaghetti of Sergio Leone also make their ways back into Hollywood and are openly claimed by movie directors, such as, Quentin Tarantino.

What becomes important here, however, is that the nature of the narrative itself changes. There is no longer such as thing as a progression to the west with a beginning, middle and the end to the last frontier but a narrative of revelation bounded with seriality which means that we do not even need to know how the story started, we are embarked into a moving train and its spirit of adventure.

Thus, narratives unfold less according to a classical logic of development of sequences than of rampant compilation and short-circuits of technological challenges. The speed of the linking of the actions, their extreme compression, thus prevents the emergence of the feeling of a time that disappears to be replace by the magic on the page and the magic of technologies on the screens. Taken together, the anticipation of an idealized forms of futuristic technologies.

In all, how personal taste and opinions preempts official critics by mobilizing some forms of universal mythologies.Hence, for example, when Elon Musk unveiled the design of his new “Starship” lunar rocket, it took exactly the shape of the Tintin one in “Objectif Lune”, minus the red and white checkerboard! A tribute to the Hergé reporter claimed by the boss of Space X. But why did the American Elon Musk take inspiration from the Belgian designer rather than from Star Wars ships?

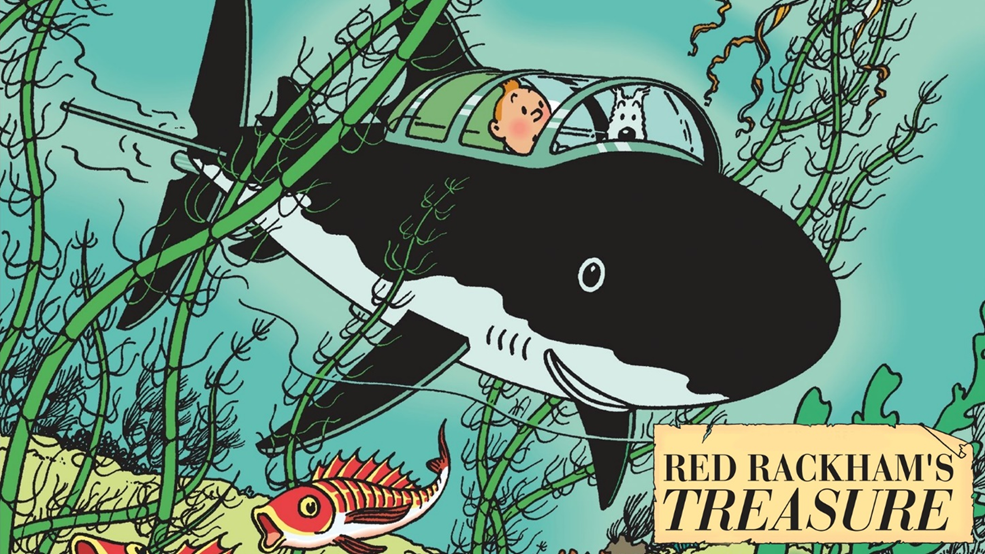

As with all his toys, such as, helicopter, plane, rocket, submarine, outboard boat, and many vehicles, Tintin has always seized, as if by magic and without a license, all the toys of technical progress. In fact, he walked on the moon as early as 1953, sixteen years before Neil Armstrong! He is a character of speed and action, of perpetual motion. He is only defined by his actions, and his interventions are always those that move the adventure forward, where the secondary characters delay the pace. Between a Captain Haddock who swears by a trillion thousand ports and a frankly tough professor Tournesol.

This is all because Tintin is both a vehicle of universal and timeless identification, but also a figure of pure freedom and self-reliance, as if spared by reality. An over-child myth that speaks to all generations of readers including space entrepreneur Elon Musk! After the "Secret of the Unicorn", the duo Steven Spielberg and Peter Jackson are reforming for an adaptation of the Temple of the Sun, announced for 2021.

Taken together, in a world that is getting hyperconnected but precarious, in many parts, these figures become the vector of a moral economy driven by technological creativity.

Response by Enrique Uribe-Jongbloed (Colombia)

It is funny that you bring up Tintin. When I was a kid in a private catholic school in Bogotá, Colombia, we were invited once a month to a “slideshow”. One of the priests at the school, an old Frenchman of the Assumptionist order, would present to us a series of Tintin slides in French, which he would then translate and act out in his accented Spanish. It was fun to hear him shout out mild curses when taking on the role of Captain Haddock. Although there were other slides in the slideshow, mostly catholic stories, we were always thrilled to get Tintin. There was adventure and excitement, and particularly for an all-boys catholic school, a role model which was, as you described, uninterested in women, ready for adventure, and with no other commitments beyond his dog, Milú.

Tintin was also part of the Sunday Funnies, a whole page on the back, and those whose families could afford it, would try to get the comic books at Libreria Francesa (French Bookstore). They were very expensive, maybe only to be expected as a lavish Christmas or birthday gift. We used to meet at the homes of those friends who possessed the Tintin books and proceed to binge-read them. They were so precious at the time, that getting a friend of you to lend on of them to you, was a proof of friendship and trust.

Of course, looking through an adult critical lens, it strikes me how those comic books always showed us Western and Eurocentric views as ideal. In that sense, it was exactly like our school curriculum and basically most media output: Westernized to the core. If they were in anyway counterhegemonic in relation to US comic book production, they remained very hegemonic from our perspective.

Obviously, despite the criticism that I might levy upon Tintin, it still holds a very important place in my heart. The only Latin American comic strip that might get close to evoking such fond memories of my childhood would be Condorito, the Chilean character, which my grandfather used to buy for me at the local Kiosk, and which is, by and large, the most famous comic book figure in the country, at least for those in my generation.

Thus, when the Tintin film came out it was almost a requirement to go watch it, more because of nostalgia than anything else. And although it was sufficiently entertaining, it was certainly not the same as remembering the old priest making up watered-down vocabulary for every “@*-!!!” uttered.

[1] Steven Spielberg and Peter Jackson played the Dupond and Dupont, in a short film, to greet visitors to the Angoulême festival and present the filming of the adaptation of "Secret of the Unicorn", on January 29, 2009