"Screen Time" in the Age of Covid-19: Reports from the Home Front (Part Two)

/Liana Gamber-Thompson: I loved reading your description of Lucca’s summer and how her love of gaming helped her navigate quarantine emotions and connect with friends. Your reflections were especially timely because over the weekend, we jumped off the precipice of a new gaming/literacy journey for my son; Wesley just celebrated his seventh birthday, and we got him a Nintendo Switch, a grand, quarantine-y gesture of unusual scale. He’s been exploring the forests of Pokémon: Let’s Go, Pikachu! all weekend, snapping up new Pokémon and battling trainers to his heart’s delight. On the parent front, I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t a little wary. It feels like we’ve entered a new dimension (of owning a gaming console) that we’ll never be able to come back from. I always said I’d wait until he was older.

Yet, in keeping with the spirit of open mindedness I promised at the very end of my intro and building on your touching observations on how gaming can lead to confidence and collaboration, I’m suppressing the urge to panic. I’m already seeing some hopeful glimmers for how the Switch might be a good supplement to his other regular activities like reading physical books, daily swimming, and watching seemingly endless episodes of Wild Kratts on the iPad.

First, best I can tell it seems like text-based adventure games (like the Pokémon game Wesley is playing) a la Legend of Zelda have won out in popularity over the arcade style games of my youth. While I have had to answer, “What does this say?” a bit more than my liking, I see Wesley making a concerted effort to sound out words and sentences on his own within the game. He’s at a point in his literacy development that he will spend hours flipping through encyclopedic reference books on animals and dinosaurs but isn’t quite confident enough to explore chapter books on his own, despite our having read every single Magic Treehouse book ever written together. I see that connecting his reading to the game play might just be the confidence boost he needs and might plant the seed for a love of narrative fiction that is largely overshadowed by his perfectly acceptable but singular love of nature anthologies.

Secondly, like Lucca, he’s already delved into the collaborative side of gaming. The morning after he received the Switch, he had a playdate with his classmate, Sean, who is by comparison a seasoned gamer. On a FaceTime call, Sean patiently explained the ins and outs of the Pokémon game and played alongside him after helping him through the seemingly epic setup. It felt nice to see them engaging in a form of cooperation that is almost entirely absent from his remote learning experience. Because his teacher is prevented from facilitating breakout rooms for privacy reasons, he rarely gets 1:1 or small group interaction with his peers while learning from home. As such, the social aspect of gaming was a draw for us as we weighed the decision to purchase the Switch at what felt like a potentially premature age.

You said something really powerful in your intro, Jessica, when you described Lucca’s gaming kicking into warp speed during quarantine. You said that, despite your decades of professional and scholarly training and your knowledge of “video gaming as [a] valuable, productive, and rich literacy space,” you still felt the weight of parental guilt. That feeling is so real. And it is so strong.

The parental guilt comes from many directions. Part of eschewing screen time is about anticipating judgment from other parents; no one wants to seem like the negligent one among their parental peers. What’s more (and perhaps I’m just easily swayed), my social media echo chamber reinforces a particular path to parental piety via depictions of perfectly curated play spaces with nothing but neutral, wooden, educational toys. The toys are always wooden! Of course, that vision of what an idealistic childhood looks like is shaped largely by privilege and whiteness, and I think it’s important to keep coming back to that point across this conversation (especially one in which I’m describing the Sturm und Drang of buying my kid a 300 dollar Nintendo).

The guilt is further codified by recommendations from medical experts. Until now, the American Academy of Pediatrics has recommended no screen time for children under two (except for video chats) and just one hour a day of “quality” programming for preschoolers. To say the least, those recommendations are purely aspirational if not downright impossible these days. Still, making a conscious break from conventional wisdom and medical advice about what’s good for kids can be agonizing, even if, like with Lucca and Wesley, we can see the good in it. I read a nice blog post by Laura Wheatman Hill over on JSTOR recently in which she reminds us that, in the 18th century, reading too many novels was considered dangerous, raising the potential for one to dissociate from reality. So, who knows. Maybe we’ll look back on this time period one day and wonder just why we were so worried about the dangers of Pokémon.

Jessie Early: Reading your words about Wesley and his newly opened Pokeman and your internal, sometimes external, dialogue questioning this parenting choice, made me smile. I feel less alone in trying to navigate this time as a working parent. Your experience helps me realize how, on top of all the juggling and stress of what we are managing right now, so many parents are feeling extra pressure to somehow get this time “right”, even though none of us know what we are doing or have ever lived through a global pandemic.

I, too, feel inundated with social media messages from parents who are backpacking with kids on weekends and making painted rocks to gift to trees and nooks and crannies throughout the neighborhood. I’ve read about “doom scrolling” , the act of endlessly scrolling social media looking for bad news. Instead, I scroll for articles and experts to reassure me that what I’m doing as a parent is ok. I jumped for joy after reading the New York Times piece Just Give Them the Screens (for Now). As my husband often tells me, “You can search for anything to tell you what you want to hear.” We all need some reassurance right now.

I also think about Wesley with his Pokeman and Lucca with her Royal High and wonder if part of our uncertainty in allowing our kids to dive into these digital worlds is a lack of familiarity? These are not the same worlds we entered as children. Give me Donkey Kong and Pac Man and I would be good to go! However, as you point out, Pac Man is lacking the complexity and collaboration and storytelling of current games. Wesley and Lucca, in their digital endeavors, grant us a chance to try to silence our internal dialogue to step back and observe. I teach a class on research methods for pre service and inservice English language arts teachers, where I ask them to step back from their teaching practice and notice and document what is happening more closely to inform their practice. This act of observation more often than not, leads teachers to slow down, reflect, and revise their teaching for the better. As teachers and as parents, the act of decentering our expertise, or admitting we are lacking any, is vulnerable and scary.

I have been sitting next to my twin 9-year-old sons as they navigate online school from home and one of the things that strikes me is how their classmates are using the chat space and time before and after the office Google Meet with their teachers to set up digital video gaming playdates. I heard one kid shout out from his little box on the screen this morning, “Who wants to meet up in Roblox after PE today?” I wonder how teachers and parents can take up these digital spaces our students and kids are diving into right now and blend them into the formal curriculum or or honor them in family conversation?

What if students could spend time designing avatars for their online school spaces and creating instructional videos to share their expertise (either digital or non) with one another? What if they got to draw and write and create new chapters or characters or worlds for the games they are playing in their free time during their class time? For kids who do not play these games, they could design and create ones that fit their interests and play, either digital or real time. There are teachers out there, many in the National Writing Project, doing this work like Joe Dillon from NWP sharing his work teaching high school students to write code for video games with Scalable Game Design and NWP Blog Radio’s blog radio show Addressing Skepticism Around Using Video Games for Learning

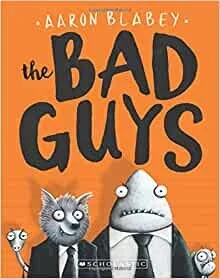

I also recognize the reading transition you describe Wesley facing in moving from picture books to chapter books. My twin boys experienced this as well and I didn’t know what to do until we discovered graphic novels! I brought home books like Dave Pilkey’s DogMan series and Aaron Blabey’s The Bad Guys series and Abby Hanlon’s Dory Fantasmagory and Nate Evan’s Tyrannosaurus Ralph and they started reading again. The mix of the visual and the textual on each page helped bridge the gap between the genres they had been experiencing (picture books) and the ones they were moving toward (chapter). I also see, from what you share about Wesley’s gaming, how video games do this too. These digital spaces allow kids to enact, build, and follow stories with characters and drama and story all with a sense of ownership and control.

Jessica Early, Professor of English at Arizona State University, is a scholar of English education and secondary literacy. She is the director of English Education and the Central Arizona Writing Project, a local site of the National Writing Project, at ASU. She began her career in the field of education as a high school English language arts teacher.

Liana Gamber-Thompson is Digital Project and Operations Manager at EdSurge, an award-winning education news organization that reports on the people, ideas and technologies that shape the future of learning. EdSurge is now part of the International Society for Technology in Education (ISTE). Previously, Liana was a researcher on youth and politics at USC, Community Manager at Connected Camps, and Program Associate at the National Writing Project. She is co-author of By Any Media Necessary: The New Youth Activism and holds a Ph.D. in Sociology.