Crisis in the Direct Market: A Virtual Roundtable (1 of 5)

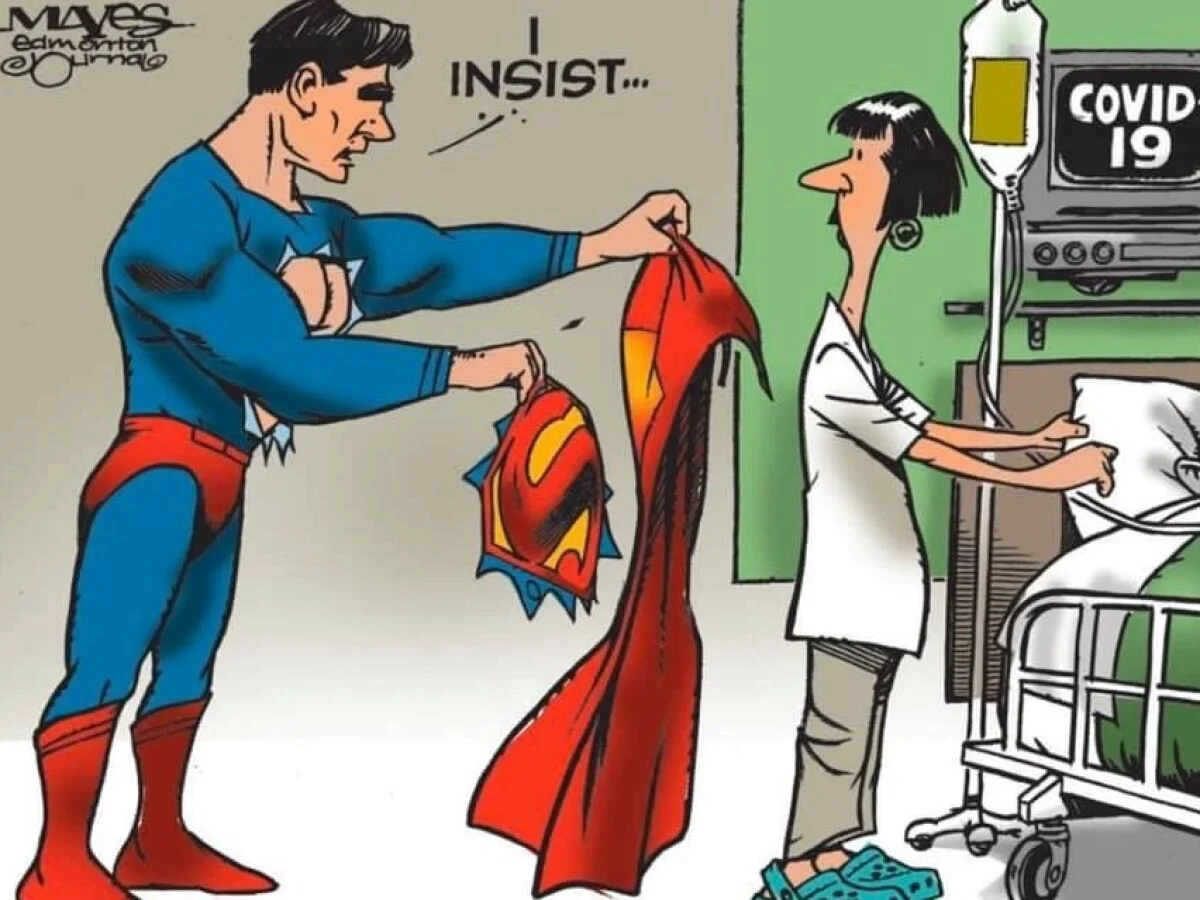

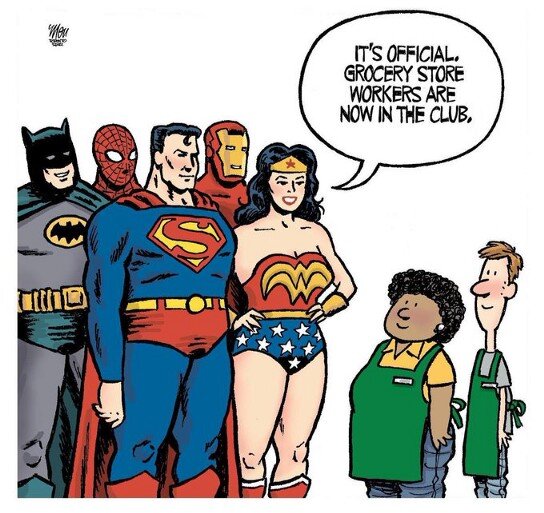

/Last week, we brought you three installments focused on the consequences of the coronavirus pandemic on the distribution of US comics. These were ‘Comics, Covid, and Capitalism,: A Brief History of the Direct Market’ by William Proctor, and ‘Is There a Way For Comics to Move Forward During COVID-19?’ by Todd Allen in two parts (here and here). This week on Confessions of an Aca-Fan , we have a virtual round-table featuring Proctor and Allen, who are joined by Shawna Kidman (UC San Diego) and Phillip Vaughan (University of Dundee) who have been discussing the implications of the current ‘pause’ on the circulation of US comics, possible solutions, and the impact of Diamond Distribution’s monopoly on the market. During the conversation, more news filtered through about decisions and key shifts, so it was a productive time to be engaged in the topic, and we hope readers think so too. You will see our usual panoply of images peppered throughout, but on this occasion, we wanted to highlight some of the art and imagery being shared online which are anchored to the theme of coronavirus, superheroes, comics, and more. It is quite moving to see what superheroes mean to so many people during times of crisis (‘crisis’ being a common motif for DC Comics).

US Comics & The Direct Market: A Virtual Round-Table (1 of 5)

Todd Allen, Shawna Kidman, William Proctor and Phillip Vaughan

WP

I’m from the UK, so my experience was a little different to the US system. As a child of the 1980s, I was unaware that we were witnessing the death throes of an entire industry as shelves were brimming with titles for both boys and girls, many of which had started in the British Comics renaissance of the early 1970s. Girls comics from Mandy and Jinty to Jackie and Misty. Boys’ comics from Battleand Warlord to The Beano, and The Dandy(and, of course, 2000AD). Today, the only survivors are The Beano, 2000AD, Judge Dredd: The Megazine, and the war comic, Commando, while a glut of franchise comics have replaced the (often radical content) of the 1970s and 80s, the majority of them relying on crappy free-gifts to attract children’s gimlet gazes. US superhero comics were available, naturally, but their arrival on British shores was not as timely as in America. Many times, we would hunt for the next issue of The Amazing Spider-Man, only to find that it was either missing or that an even earlier issue was released retroactively. Jumble sales were one of the ways we might find missing issues, but until the Direct Market, superhero material was difficult to find in chronological terms. I have heard that US comics were often used as ballast on ships at the time, and that issues were shipped out-of-order, if at all. Of course, we had annuals that we would receive every Christmas, but until the rise of specialty comic retailers, superhero comics didn’t rule the roost. This could simply be my own experience, however, as Marvel had a UK imprint during the 80s, but I didn’t engage that much with the content until much later (although I did regularly purchase Transformers, which was published by Marvel UK). Maybe I’m misremembering (which is entirely possible!). What is interesting is that during the current lockdown, I’m still receiving my 2000AD, Judge Dredd: The Megazine, Rebellion’s new series of old British comic titles (with all-new material. I have purchased the latest issues of Commando on eBay, and I even bought The Beano at the supermarket the other day. Why is this? I think Philip Vaughan will be able to answer this best.

PV

Much like Billy, my early memories were getting my comics from the local newsagents. I have vague memories of the early 1970’s, and getting some pocket money to go to the shops to buy sweets and comics. The choice of publications seemed endless, and 20p could go a long way! I distinctly remember buying the Marvel UK version of Star Wars Weekly, the comic adaptation of the film for 10p from the newsagents at the bottom of my street (in 1978, yes we actually had to wait for this in the UK!). It was somewhat disappointingly printed in black and white. This was supplemented by a weekly delivery of The Beano and The Dandy, humour comics from local Dundee comics powerhouse DC Thomson. These comics were delivered with my parents' local newspaper, The Dundee Courier. This gave me early exposure to comics as a medium. So newsagents, and to a lesser extent, supermarkets were stacked with plenty of comics which included British classics like The New Eagle, Tiger, Roy of the Rovers, Victor, Warlord, Commando and of course 2000AD. I would not graduate to the more adult 2000AD until around 1984. Back to Marvel UK, and they had the reprint market pretty much sewn up. I was aware of a few titles, all of which reprinted the US comics, but in black and white. Again these were freely available in newsagents. But things were starting to change. A turning point for me was the UK reprints of both Transformers and Secret Wars. The Transformers comic produced by Marvel UK was a clever blend of full-colour US reprint material and freshly commissioned UK strips by top British talent. Secret Wars was the start of ‘event’ comics, and by the time it moved onto ‘Secret Wars II’, crossover comics were well and truly underway in the US. We were lucky that we got the crossover issues pretty much provided for us in one comic, to a certain extent! Again these publications were readily available and accessible at the local shops. But I started to notice one-off copies of Marvel and DC comics appearing in certain newsagents. They would usually have a COMAG sticker on them, were on import, and generally were sporadic issues of popular titles like X-Men, The Amazing Spider-man, The Incredible Hulk, Superman and Batman. I was amazed to find out though that these could be ordered to the newsagent, along with my regular UK comics! This was a revelation. Plus the cover price, whilst higher than UK comics, was not too prohibitive (40p if my mind serves me right). At this point, I didn't even know what the direct market in the US was, as we had a pretty good system here in the UK and I assumed it would be similar in other countries. This system UK hinged on the ‘Sale or Return’ philosophy of comics publishers; the retailers took no risk on the comics they received.

The biggest change to my comic buying habit though started in 1989, when I learned that there was a dedicated comic shop housed within an indoor market here in Dundee. This ‘shop’ was called ‘The Black Hole’ and it operated pretty much like an american comic retailer, as far as I could tell. There was a listing guide, and you could tick off what you wanted from a large list of US publishers including Marvel, DC, and smaller publishers like Dark Horse. This indeed was a game changer for me. I did not know it at the time, but my comics colleague at the University of Dundee, Chris Murray, would also frequent this establishment! The main difference in this set-up was that the stock could not be returned, comics which were not collected became back-issue stock. A burden to the retailer really.

So, what does this tell us about the different systems between the US and the UK? My observation here during the lockdown, is that, as of yet, the distribution has not been affected much at all. WHSmiths, the biggest high street provider of magazines and comics has shut down a number of its stores (hopefully temporarily), however you can still get the comics which are still being published (such as The Beano, 2000AD, Judge Dredd Megazine, Commando and even some of the Panini Marvel/DC reprints) from the larger supermarkets that are still open during the crisis. From an outsider's point of view, the comics industry in the US is in crisis, with direct market retailers shutting down, some for good, and many creators being told by the publishers to put their ‘pencils down’. In the UK, freelance creators are still being commissioned as per usual. We also seem to operate a more robust subscription model. I have been a subscriber to 2000AD/Judge Dredd Megazine for over 15 years. So far the deliveries and issues have been uninterrupted. I am unsure why the subscription route has not been taken in the US, is it to do with issues over printing, or distribution? The Diamond monopoly was always a problem waiting to happen, and this has exposed how precarious the US system really is.

I have not even touched upon digital distribution. There is obviously a resistance to this from most ‘bricks and mortar’ retailers, which I totally understand, however the comics industry is way behind innovations in other mediums such as streaming TV/Film services, iTunes/Spotify music distribution and even book distribution via Kindle etc. Digital comics and the interfaces designed to view them have just not captured the imagination of most comics readers. This does mean that if the printed material cannot be distributed, then the entire industry grinds to a halt. Most continuing US comics are in limbo right now, and I do hope they survive this hiatus, but it seems there was no contingency plan whatsoever, and this is a shame for the retailers, publishers, readers and creators alike. No one really wins here.

WP

I think it’s worth exploring further if a US subscription model of the sort we have in the UK would have made all the difference. Is the primary reason for not doing this anything to do with Diamond’s monopoly? I’m thinking that a subscription service would effectively cut Diamond out of at least some of their distribution power? I suppose subscriptions would usually be arranged through the publishers rather than the distributor, thus providing alternative circuits that maybe Diamond would push back on to maintain their grip on the industry. Perhaps Todd Allen has some thoughts on this.

TA

The decline of subscription services over the years have probably been a combination of a few things. If you go back and look at the house ads in American comics of the 1970s, you'll see plenty of ads for subscriptions, often full page ads and usually with a discount involved. Buy two and get the third free, that sort of thing. As the Direct Market started to take hold in the 80s, I think towards the end of the 80s, those subscriptions offers got phased out. Direct Market retailers can be extremely possessive about the comic market and generally complain any time a new market opens or if someone outside the DM is offering a discount (the driving reason why new issue releases in digital are at print list price), so I can’t imagine that retailers weren’t complaining about subscription discounts. On the publisher side, as the business started to move towards non-returnable sales to the Direct Market and away from advertising as a larger revenue stream, I suspect the profit and effort of processing discounted subscriptions may have been less appealing and been a factor in it being discontinued. I can tell you that when Marvel decided to cancel all the secondary Spider-Man titles in ‘08 and instead release Amazing Spider-Man three times a month, they offered a substantial discount to anyone who wanted to subscribe. I want to say it was 30% or 40%. The retailers screamed so loud, you’d have thought someone had come into their individual stores and robbed them at gunpoint. And from the perspective of those retailers, that’s what had happened. Until the collected editions started picking up steam in the bookstores, the DM retailers were the only game in town for the publishers and they guarded that status like a jealous god for as long as they could. For single issues, they’re still the only game in town. Subscriptions are a textbook example of channel conflict between retail and manufacturing. I used to use it as an example when I was an eBusiness professor because it was such a no-shades-of-grey case study.

For the collector side of things, let me start with my anecdotal experience with subscriptions in the mid-80s. In 1984, I was living in a small rural town and didn’t yet have access to the Direct Market. DC was starting to launch some DM-only titles like the “Baxter” (better paper) editions of New Teen Titans and Legion of Superheroes. The only way I could get New Teen Titans was a subscription and I’m not sure if there was much of a discount on it at the time. I still remember having to do a lot of convincing over the price of a subscription, but that could have been because those Baxter books were so much more expensive than the regular titles. And around this time Marvel started reprinting their Doctor Who comics from Doctor Who Weekly/Monthly… again, DM-only, Baxter format. That one was a bundled discount and I want to say I also had subscriptions to Avengers and X-Men. I think perhaps my Grandmother got me that. Here’s the thing about subscriptions - back in the ‘80s (and I would assume at any time leading up to the 80s), subscriptions sounded a lot more normal to adults than going to a store that sold only comics and was frequently in a dodgy neighborhood. And if there was a discount attached to the subscription, well that was what “normal” magazines did and they were saving money.

The downside to this, and my experience seemed to be typical, was a number of inconveniences. First off, you never knew how beat up a comic would be by the time it arrived. Pure mint wasn’t likely, but sometimes you’d get near mint. Every once in a while, you’d get an issue that was absolutely mangled and you might want to be extra gentle while reading it, which wasn’t cool. Every now and again, an issue would fail to show up. Which could be a royal pain with serialized stories and not always easy to replace because of timing. And timing was part of the inconvenience of subscriptions. You weren’t always sure when it was going to show up. My recollections may not be precise after all these years, but as I remember it, Direct Market comics would show up one or two weeks before the newsstand editions and then the subscription copies would arrive another week or two after the newsstand. So if the mail (or perhaps the processing of subscriptions) was running a little slow, you could be a full issue behind and by the time you were sure they’d forgotten to send you an issue, it might still be available - or worse, you could get charged extra for a back issue.

Which is to say, reading copies only and you’d best not be in a hurry to read it. If you were a collector, it wasn’t the best system. I recall my mother being mystified that I was getting them later than the newsstand. Whatever Better Homes & Gardens type magazine she subscribed to arrived at the same time or earlier, so I’m thinking the comics publishers didn’t put the same attention to subscription as the glossy magazine publishers did. Then again, comics were never ad revenue-driven like the glossies.

When I finally got access to the DM, and particularly when I was able to drive myself to the shop, I transitioned out of subscriptions. More timely, ultimately more reliable and I didn’t have any mangled copies unless I chose to buy a mangled copy.

As the US market shrank and become more of a collector market and less of a reader market, the subscriptions became less viable. They were never really intended for collectors.

SK

Even with all of the resistance and problems you describe here, it's surprising to me that a large-scale subscription service or digital-based distributor hasn't stepped in (against the will of both Diamond and the retailers) to remake the entire market. (ComiXology is doing this on some level, but it hasn’t actually changed fundamentals or upset existing infrastructure). That’s not true for every other media business, with companies like Spotify, Netflix, Amazon, Steam (the list goes on and on), wreaking havoc on retailers big and small, and undermining established distribution companies with a lot more capital and power than Diamond has ever had. And remember that Netflix and Amazon both started selling physical media products, but in a way that was streamlined, affordable for consumers, utilized the mail system (which alas, may now be at risk…), and served fans very well. Why has there been no interloper in this business? Perhaps it's just not a big enough market to attract investment and interest?

Regardless, readers have shown considerable loyalty to both the physical product and the physical stores they buy them in. Those spaces provide a sense of community, as do comic book conventions. This is a face-to-face, touch-the-product, gather together, kind of business. Perhaps that has been its armor for all these years, its protection against a tech takeover. Which is why this current crisis is so worrisome and might also have the potential to upend the current system. Even once the economy "reopens" people are very likely going to want to avoid public spaces as much as possible, and large gatherings and conventions are unlikely to come back at all, at least for the next 12-18 months. That could mean a kind of rupture in the system and could be, as all of you note, particularly bad for retailers. I would say that the possible demise of Diamond could be a kind of silver lining here, but I just don't know what might emerge in its place.

Crisis or not, I think another way of thinking about this is asking where change emanates from--who the likely instigators will be and how that might impact the medium's future. Will it be from outsiders? Investors buying up parts of the business on the cheap? Or from within? From small-scale innovators with big ideas? Or established powerhouses with lots of capital? Perhaps Amazon/ComiXology will become a more aggressive presence and move into print? When the industry faced trouble in the 1950s, it was the big players, the center of the established industry--DC, Archie, Dell--who took control and dictated what the business would look like in the future. They took over distribution and they crafted the Code; everyone else just had to follow along with their (rather narrow) vision. In the 1970s, though, it was the Underground and indie publishers who brought change by introducing the direct market. Once they proved that it worked and pointed the medium in a new direction, DC and Marvel adopted it, and the current system was born (for better and worse, depending on the decade or the issue). At this point, DC and Marvel are not in a position to innovate. They are beholden to their parent companies who have much bigger fish to fry. And retailers and small publishers will be struggling just to survive. So who is likely to lead the way in this time of crisis?

The truth is, as a historian, I don’t feel like I can offer a great deal of insight into the short term impact of this crisis or the possible resolutions. Instead, I find myself thinking about the long term trajectories of the business. Where was comic book publishing heading two months ago, and how does Covid-19 impact that? Does it just amplify and/or hasten a transformation that was already underway? Or does it actually change the industry’s course, and set it on a new path forward?

WP

Great questions, Shawna! I think your point about whether the pandemic is amplifying or hastening a transformation, or transition, that had already started is worth delving into. I did my PhD on reboots (which I’m currently retconning into a monograph) and I charted the term itself, its etymology, its first uses as a way to describe superhero comics that wiped the slate clean of continuity in order to begin again from scratch, mainly in the quest for that fabled demographic—the new reader. But I also aimed to historicize the economics of the industry from its heyday at its inception (the Golden Age), its resurgence in the late 50s (the Silver Age), its downturn in the 70s and 80s, before the Direct Market emerged and (seemingly) solved many problems. So, the cycle of boom and bust interests me, but also the way in which reboots, and other associated “strategies of regeneration” (event-comics, retcons, relaunches, generic refreshes etc) have become mobilized more and more as the decades passed. (As an aside, I also aim to establish conceptual distinctions between these strategies as many journalists and academics use the terms interchangeably, which is of course a discussion for another day). Todd emphasizes the litany of relaunches in the 2010s early on in his excellent book The Economics of Digital Comics, and I think it’s worth exploring here in response to Shawna’s queries as it indicates just how fragile the market already was prior to the pandemic.

In fact, it’s probably fair to say that since at least 2005, the big two have found it necessary to head from event-series to event-series, and relaunch to retcon to reboot: Infinite Crisis, Final Crisis, Flashpoint, ‘The New 52,’ Marvel Now, All-New Marvel Now, Convergence, Rebirth, Doomsday Clock, etc. As Todd points out, there have been gains in some cases following relaunches, but these gains tend to drop off significantly (hence, requiring another sales generator). After The New 52—or as I saw older fans calling it at the time, ‘The Ewww 52’—DC did overtake Marvel for a time, but then the lower-charting titles ended up being culled, and sales declined. As we know, new number ones always sell more—that old speculator myth is to blame; that number ones fetch a higher profit margin later in the day, an absurd notion when we’re talking about books that have high-print runs. So the constant renumbering and relaunching indicates an industry in crisis. It was nine years between the conclusion of Crisis on Infinite Earths in 1985-86 and the next attempt at rebooting the universe in 1994 with Zero Hour: Crisis in Time—which didn’t reboot the universe at all, but certainly led to the reboot of The Legion of Superheroes (which incidentally was the first time the term reboot was used to describe a media franchise beginning again from scratch). Julius Schwartz said, “every ten years, the universe needs an enema,” but what we’re seeing in the 21st Century is an almost constant, if inconsistent, shaking up their respective lines on an annual basis. Of course, this has also been criticized by fans, some of whom complain about “event-fatigue,” and the symptoms of this hit Marvel hardest of all when they published Civil War II in 2016, and sales started to decline as each issue arrived. I would suggest that rather than boom and bust, we are witnessing micro-booms and micro-busts on an almost continuous basis (Todd may have additional thoughts on this). Marvel’s ‘flood the zone’ strategy has largely backfired. Comic store owner Brian Hibbs claimed that the industry “is on its knees” early in 2019 (so well in advance of COVID). He said:

"National sales are very poor – there are comics in the national top 100 that aren’t even selling twenty thousand copies. A significant number of stores have closed — perhaps as many as 10% of outlets," Hibbs said. "Want a clear and current example of Marvel’s preposterous 'flood the zone' strategy? War of the Realms is supposed to be their major Q2 project in 2019, but in the first month alone they’re asking us to buy into TWO issues of the series being released with no sales data, as well as FOUR different tie-in-mini-series. All six of these comics (which are built around a six-issue storyline) will require final orders from us before we’ve sold a single comic to an actual reader. Is there anyone in this room thinks that this is good? That this is sustainable? That this will sell more comics to more readers? That this will sell any copies to people who aren’t already on board Marvel’s periodicals already?"

My local comic book retailer is often up-in-arms about the overproduction of books, his chagrin centered on the fact that, in his mind, the publishers won’t listen to retailers or readers. In fact, the main reason that I have stopped buying floppies over the past couple of years—it’s like an addiction, I needed to wean myself off—is that I cannot condone the amount of money I was spending to keep up-to-date. At one point, it was over £200 per month. And then 95% of what I read wasn’t great, either. So I’m a trade guy now, more or less, and will pick up books that have been reviewed well by fans and reviewers that I trust. So well done to DC and Marvel for forcing my hand (and maybe others too, if sales are to be believed). So in a nutshell, I would say that you’re right to ask if the pandemic has hastened what was occuring at any rate (although my more cynical self would argue that it wouldn’t matter much as there seems to be a power struggle between retailers, publishers, and Diamond). I hear that Jim Lee is auctioning off sketches, with proceeds going into a fund to support retailers on the cusp of collapse. Perhaps I’m being unkind, but this is not as altruistic as it might seem. As Chief Creative Officer for DC Comics, he is well aware that losing retailers means losing profit centers for books (there’s that cynical self again! I’m a comfortable Marxist, so I tend to look on the darker side of capitalist enterprises).

One of Jim Lee’s sketches for auction: Stephanie Brown as Batgirl

In your book, Comic Books Incorporated, you show how licensing overtook publishing in the 1970s, Shawna. Obviously, this situation has accelerated in the 21st Century since Bryan Singer’s X-Men and Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man raked it in at the box office—and let’s not forget, DVD sales that make more money by a wide margin than cinemas per se (which is also changing with streaming etc.) Do you think that comic books have been on the endangered species list since the 1970s, Shawna? Are comic books more a Research and Development portfolio for blockbuster films, TV series, and other transmedia expressions, as Dennis O’Neil complained a while back (and academics like Derek Johnson, Will Brooker, and others)?

TA

Lots to unpack here, so let’s take it in order.

On the lack of a digital distributor coming in, that’s an incredibly complicated topic. I’ve been down the startup path a couple times, personally, so I can speak with experience here.

If you want to have a comic *book* digital distribution startup, you need a LOT of money. Tech staff is not cheap and a lot of the people you want will live in expensive cities. SF, NYC and LA do not make for a low payroll, nor does tech. You’re going to need to spend a LOT on advertising. Some of the publishers are going to demand some upfront money before content is handed over.

A lot of the deep-pocketed Venture Capital firms absolutely do not get content plays. Particularly in San Francisco. That’s my theory on why Transmedia has never taken off up here: too much emphasis on engineering. This is compounded by needing to compete with Amazon, which a lot of VCs are very reluctant to do. That’s in turn compounded by Amazon having Marvel on an exclusive contract. It makes it more difficult to raise the big money.

If you go for the smaller money, what you’re likely to hear is “well, can’t you build out this little part of it and then we’ll see how it’s doing in six months?”

That’s actually the most self-destructive thing you can do. We’ve seen what launching with an incomplete set of publishers and a shoestring budget looks like and it simply hasn’t worked.

If you look at the webcomics world, WebToons has made a lot of noise by launching with a selection of established Manga/Manhwa and building audiences for new material around that, along with some pre-existing webcomics. If you look at Tapas, they operated off the same template.

If you want to play in the comic book world and you don’t have DC or Marvel to be your primary traffic driver, you’re going to need a couple years of runway and a marketing budget to grow that audience.

Really, comics are unusual in exactly how small a community it is. Whether it’s print or digital, there are so many exclusive deals you just don’t see in other types of publishing. It’s great for the entity holding the exclusive, but it’s terrible for competition and innovation.

It also doesn’t happen that there have been some spectacular crash and burns in this space. When I was with Aerbook, we specifically had investors point at their huge disappointment with Graphic.ly, which would be formally dissolving a few months later. Some of the wells have been poisoned, on top of it being a content play and on top of competing with Amazon.

There will be another player. Honestly, most of the publishers want one. Nobody likely being trapped in one and a publisher, whose identity I’m going to protect in this instance, once told me “we traded in Diamond for Amazon.” The question is how long that’s going to take to happen.

Now, all that said, a new player wouldn’t change anything if the publishers won’t release the books and I do think releasing serialized single issues when most of the retail channel has been forced to close the doors will cause more long term problems that it fixes. If you’re a publisher, you shouldn’t want to kill your primary channel. You should want to growing all your channels and becoming less dependent on a single one.

Alas, long term planning has NOT been a hallmark of comics publishing in a very long time. Things tend to be about grabbing cash as quickly as possible. And really, if the quarantine is slow to lift and/or we have a repeat in the Fall, short term survival is going to be the only priority for a lot of people. This is uncharted territory.

With the explosion of low circulation titles, you’ve got a couple things going on.

Historically, DC and Marvel (especially Marvel) have been known to flood the shelves to keep shelf space away from smaller players. You used to hear a LOT of complaints about this going back to the 90s. That’s not always going to be the case today, but there may be a kernal of that in the current situation.

What’s happening now seems to be publishers deciding they can keep the lights on more easily if they have 30 low selling titles, than trying to get 10 titles to sell large amounts.

It’s a little easier to describe this for the indie publisher. Indie publishers have a hard time getting over 10K in sales for a single issue. For that matter, 5K copies is a victory for a lot of them. That’s just what the market has been dictating for the last decade or so. If a publisher bundles their printing to get the unit cost down... If the publisher prints overseas in some cases, to get the unit cost down a little more… If the publisher’s page rates are low enough… you add all this up and suddenly the publisher is able to see some minor profit on titles that sell 3K-4K. And if you have the editorial capacity to publish enough of these smaller titles, that sliver of profit adds up and you keep the lights on.

What many of the indie publishers found was that the market would support a lot more 3K titles than anyone had previously supposed.

DC and Marvel, particularly Marvel, are just doing this with higher profile titles. Still, a 12K circulation book for Marvel is a lot more like a 3K circulation book for an indie. It’s how they’re making their quarterly numbers. And make no mistake about it, Marvel is a business that emphasizes their numbers.

The truly ironic thing here is that this publishing model works a lot better for digital than brick and mortar retail. In digital, you have infinite shelf space. In digital, the shop is paying a royalty on what sells, not buying issues on a non-returnable basis and hoping they sell, tying up working capital with that gamble.

This has evolved into the current reality where more and more stores are ceasing to order the entire DC and Marvel lines for the shelf. A lot of these titles are in-store subscription only. Without a shelf presence, these titles will have a very large problem gaining new readers and will be more susceptible to reader attrition. It’s usually a death sentence and if you look at it from the perspective of how someone browsing in a shop would find such titles, it’s no wonder that it’s a revolving door for these small titles. The mechanics exist to extract cash from the big fish who have in-store subscriptions for as long as they’ll tolerate the title and then throw a new one at them. And, of course, to issue a cornucopia of variant covers for the speculators for that new #1 when the replacement series launches.

Is this healthy? Not really. But it’s kept the lights on for the publishers up and down the sales chart.

This system can work for retailers if they have enough large selling titles (like how Batman used to sell, and the indie friendly shops really miss Saga), then those cash cows can mitigate the risk of stocking smaller titles for the shelves. Which is to say the retailer is making enough on Batman that it doesn’t matter if a couple issues of a third tier Spider-Man spin-off and a couple indie titles didn’t sell through this month. Big selling cash cows create the fudge factor for a store to have a complete line.

This is one of the reason why I’ve always looked at the sales charts in terms of sales bands. It tells you how healthy the retail side of things is.

Would dropping the number of titles published increase the circulation of the remaining titles? For DC and Marvel, yes. That seems likely and it might solve some of the problems of the retailers. The thing is, I’m not convinced it would mean more money for DC and Marvel and they’d have to sell that dip in operating income to corporate, were it the case.

For indies, I’m not sure whether you’d see a particularly drastic change or not. There are a lot of niche audiences aggregated in independent comics and you’d need to look at the individual segments. Would it change things enough to help retailers? I’m really not sure how big a difference that would make, past the retailers stocking a larger percentage of titles. You’d need to have a serious conversation about that with the 250-350 stores that are heavily invested in independent comics.

Todd Allen is the author of Economics of Digital Comics. He covered the comic book industry for over a decade reporting for Publishers Weekly, Chicago Tribune, The Beat and Comic Book Resources. As a contributing editor to The Beat, his work has been nominated for an Eisner and named to TIME’s Top 25 blogs of 2015. He was admitted to the Mystery Writers of America for the Division and Rush webcomic. He taught eBusiness in the Arts, Entertainment & Media Management department of Columbia College Chicago and has consulting on digital topics for organizations like American Medical Association, National PTA, McDonald’s, Sears, TransUnion and Navistar.

Dr Shawna Kidman is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Communication at UC San Diego, specializing in media industries. I write and teach about broadcast and cable history, streaming content and digital distribution, copyright law, media audiences, and contemporary issues related to pop culture and society. My newly released history of the comic book industry explains why comics are ubiquitous in Hollywood, and how they came to take over corporate multimedia production of the 21st century. Covering 80 years of history, I show how many current trends in the media business—like transmedia storytelling, the cultivation of fans, niche distribution models, and creative financial structuring—have roots in the comic business. As a result, even though comic books themselves have a relatively minuscule audience, and have suffered declining sales for decades, the form and its marquee brands and characters continue to gain in global prominence and popularity.

Dr William Proctor is Principal Lecturer in Comics, Film & Transmedia at Bournemouth University, UK. He has published on an assortment of topics related to popular culture, and is the co-editor on Transmedia Earth: Global Convergence Cultures (with Dr Matthew Freeman, 2018 for Routledge), and the award-winning Disney’s Star Wars: Forces of Production, Promotion and Reception (with Dr Richard McCulloch, 2019 for University of Iowa Press). William is currently working a history of comic book and film reboots for Palgrave Macmillan titled: Reboot Culture: Comics, Film, Transmedia.

Phillip Vaughan is a Senior Lecturer and Programme Director of the MDes in Comics & Graphic Novels at the University of Dundee. He has worked on productions with the BBC, Sony, DC Comics, Warner Bros, EIDOS, Jim Henson and Bear Grylls. He also has credits on published work such as Braveheart, Farscape, Star Trek, Wallace and Gromit, Teletubbies, Tom & Jerry, Commando and Superman. He is the editor of the UniVerse line of comics publications and also the Art Director of Dundee Comics Creative Space and the Scottish Centre for Comics Studies.