Comics, COVID and Capitalism: A Brief History of the Direct Market

/Comics, COVID and Capitalism

By William Proctor

Never has the term “these are unprecedented times” become such a cliché so swiftly. As the global death toll continues to climb on a daily basis, the coronavirus pandemic shows no signs of letting up, plummeting the world into a genuine crisis that we have not seen for generations. As much as COVID-19 infects our citizens and our families, it has also spread virulently into the corporate organs of the economic body, with global neoliberal capitalism confronted by as perfect an enemy that it has ever faced. Since at least January 2020, it has become clear to many that the pandemic has exposed numerous weaknesses within the arteries of capitalism, its veins and arteries struggling to pump nutrients to its most vital organs. In a sense, the pandemic has exposed the capitalist system as a fragile, diseased thing. In the context of all this turbulence, turmoil and tragedy, it is perhaps very much a ‘first-world problem’ to think about the commercial shock-waves rippling throughout the comic book industry. Yet it could most certainly be argued that examining the current distribution model for US comics, undergirded as it is by one major corporation—Diamond Comics Distributors—may provide insights into the impact of coronavirus on the stark economic realities that we are now facing, also allowing for a teasing out of the problems and pitfalls with the distribution system as it currently stands; an unfair, inequitable, and monopolistic system that may have, to some extent, ‘saved’ comics during the 1980s and ‘90s, but has over time grown increasingly problematic, to say the least. To most comic fans, retailers and scholars, the history is well-known, but it is worth offering a very brief history of what is known as The Direct Market. Prior to the Direct Market, comics were distributed to news-stands and news-agents, in the same way that magazines were (and in many cases, continue to be). Some of us will fondly remember spinner racks in newsagents and Mom and Pop stores, shelves buckling under the weight of so many four-color treasures. New-stand distribution, however, ended up severely cramping the commercial potential of the comics medium. As Shawna Kidman emphasizes in Comic Book Incorporated (2019), the market during the 1950s and 60s may have seemed in rude health, publishing in excess of 500 hundred comics each month, but the market became strained by too much content that the news-stands simply did not have the shelf-space to carry, not by a long chalk (the average being 65 in Kidman’s account). There was also “an oversupply problem with physical and financial repercussions, reports of entrenched anticompetitive practices, and souring relationships between distributors and retailers along delivery routes. Demand was also in critical decline” (Kidman 2019, 49).

Like all good media histories, Kidman expertly punctures more than a few myths in her book, perhaps the most notable being the impact that Fredric Wertham’s anti-comics crusade had on the industry. Although not the only genre in his rifle-sight, Wertham attacked superheroes for various reasons. In his view, Batman comics promoted homosexuality due to the living arrangements at Wayne Manor, with Bruce, Dick Grayson and Alfred participating in a gay ménage-a-trois (of course, as Will Brooker has shown, .Batman was open to gay readings very early on).

Moreover, Superman was a “symbol of violent race superiority” who “undermines the authority and dignity of the ordinary man and woman in the minds of children,” and moreover, unfairly made children believe a man could fly. Wonder Woman was little more than “a veritable lesbian recruitment poster.” However, the DC Trinity—Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman—continued to be published throughout the so-called ‘comic book scare,’ and as we know, it was crime and horror comics that came under the close scrutiny of US senators, leading to the collapse of E.C Comics (and by extension, the self-regulatory Comics Code). It was the senators that highlighted the crime and horror genres as cause for concern, not Wertham, who worried more about ‘jungle comics’ and, to a lesser extent, superheroes, as Kidman highlights.

Editor Julius Schwartz successfully revived the superhero genre in the 1950s with reboots of The Flash, Green Lantern, The Atom, and Hawkman, giving birth to the so-called Silver Age in turn. In 1961, the publication of Fantastic Four #1 and the ascendancy of Marvel Comics began chipping away at DC’s market hegemony. Yet by the time Marvel eventually overtook DC as market-leaders in 1971, the same issues related to news-stand distribution came back to the fore. Sales were declining across the industry, but DC felt the brunt of market-forces more than Marvel—who has been saved by Star Wars, according to Jim Shooter—and ended the decade on the ropes. Prices went up, sales declined, distribution halted for a time due to horrendous storms across the East-Coast, and recession began to bite. New DC editor Jenette Kahn’s company-wide initiative, The DC Explosion, failed so dramatically that it has become known as ‘The DC Implosion’ in fan and industry circles. It was also in the 1970s that revenue from licensing outstripped publishing for the first time, and DC’s new corporate masters, Warner Communications, saw comics more as an IP farm for other endeavors, especially film and TV. As Kidman points out, comics became “a loss leader for Warner’s other entertainment subsidiaries,'' and domestic publishing began to lose money. Enter the Direct Market.

In many ways, the Direct Market was inspired by the way in which underground Adult Comix circumvented news-stand distribution, their wares being sold mainly in head-shops (probably by necessity as news-stands wouldn’t carry Adult Comix due to their seditious nature). Established by comic-con organizer Phil Seuling, the Direct Market would largely do away with news-stand distribution, triggering the rise of specialty comic book stores that continue to dominate the market today. As a result, the American comic book landscape changed dramatically in the 1970s and ‘80s (although it wouldn’t be until the early 1990s before the new system completely did away with news-stand distribution).

It may be true that the Direct Market would prove to be a nostrum for the struggling industry, but over time, it expanded into a monopoly, one that would arguably create the largest burden for retailers, not publishers. This would have a knock-on effect for the smallest, independent retailers most of all. Prior to the Direct Market, publishers sold their fleet of titles to news-stands and newsagents on a ‘sale-or-return’ basis, meaning that publishers agreed to ‘buy back’ unsold items, which worked very well during the boom years in the 1940s when over 70% of print runs were sold, yet became unsustainable as readership declined. In the Direct Market system, retailers do not have the luxury of the sale-or-return safety net: if titles didn’t sell, then retailers would be left to foot the bill. I have witnessed the impact of this model on small, independent outlets, such as Paradox Comics where I live in Bournemouth, UK. Its owner Andy Hine often expresses how tough it is to order the right number of comics, which titles, and how many. Of course, he can order the titles for those readers who have a regular pull-list, but knowing how many to order for the shelves so people can pop in and pick up a title is almost impossible to determine. With so many relaunches and reboots in recent years, it is a dizzying task to know the best route to take if Andy is left with comics that he can’t sell nor return. While large corporate franchises such as Forbidden Planet may be able to absorb the costs of mass ordering, independent retailers like Andy cannot do the same.

This situation has led to a significant contraction of the number of comics retailers in the decades since the Direct Market was established, lending weight to the naked fact that even superhero comics are less a form of popular culture nowadays than an insular subcultural ghetto (despite the genre appearing to be as healthy as ever with the proliferation of blockbuster films and TV shows dominating the landscape). As former Vice President of Product Development for Crossgen Entertainment, Tony Panaccio, explains in Todd Allen’s The Economics of Digital Comics (2014):

“In 1992, there were about 10,000 retail specialty shops that made up what we called The Direct Market…[in 2014], that number is reduced dramatically lower and somewhat in dispute. Promoters of the industry claim that there are as many as 3,500 in operation [in 2004]. After three years of canvassing, via phone, Internet and direct-in-person contact, [we] were able to ascertain the existence of only a little more than 2,000 such Direct Market specialty shops for comics last year” (2003).

Three of the largest distributors in the 1980s were Capital City, Heroes World, and Diamond Distributors. In 1994, Marvel acquired Heroes World so it could use it as its exclusive distributor but as written by Alex Hearn for New Statesmen, this

“landgrab led to every other publisher to attempt the same thing, but by the end of the next year, it was clear that the diseconomies of scale that that fragmentation introduced were unsustainable. Distributors started to fold, until just one, Diamond, was left. When an editorial initiative in early 1997 failed for Marvel, they signed up with Diamond we well, guaranteeing one company a stranglehold on the industry.”

In 1997, Diamond’s position as “the sole source of most new comics products to comics specialty shops” saw the company investigated by the U.S Justice Department (DOJ) for alleged antitrust violations and market monopolization. However, on November 6 2000, the DOJ concluded its investigation, claiming that “legal actions because of allegations of monopolistic practices are unwarranted,” the reason being that publishing is a much larger universe than comic books, thus Diamond did not benefit from a monopoly on book distribution per se. Tony Panacchio expressed his discontent with this decision, again captured by Todd Allen:

“In my mind, Diamond is one of the worst cases of monopoly in American publishing, and the resulting power and influence wielded by Diamond in the marketplace is unfair and illegal. It is fundamentally unjust that this criminal conduct is allowed to continue while thousands of retailers, thousands of creators and dozens of publishers locked outside the premier vendor club suffer under a system that was constructed solely for the purpose of entrenching and rewarding a select minority […] Diamond’s primary business model is to shrink the comics industry down to its lowest common denominator and squeeze out any potential competition for its premier publishers.”

Although Todd Allen stresses that Panacchio’s view “is an extreme one,” he also states that there is “at least circumstantial evidence to take this viewpoint seriously.” And given what has happened more recently to comics publishing during the pandemic, I strongly believe that Diamond’s iron-fisted grip on the industry has now become counter-intuitive; and perhaps that’s not a bad thing.

That being said, there have been rumblings that the Direct Market has been under pressure to shift its model in recent years. On the website Pipeline Comics, Augie De Blieck Jr wrote in 2018, that we were in the midst of a “retail apocalypse,” that the Direct Market “as it exists today is doomed,” that comics publishing is not as profitable a venture as it was during the medium’s heyday (and that’s being diplomatic).

“there’s too little profit in selling $2.99 or $3.99 comics, with too few buyers who want to pay that much for a monthly comic [or as the case may be, bi-monthly, or even weekly]. With those razor thin margins, who’s getting paid? The retailers, who get nearly half the money from every comic sold, but still can’t sell enough to stay alive? The distributor who, if it wasn’t effectively a monopoly and didn’t ship ‘The Walking Dead’ trades, might as well be dead already? The publishers, who have big fancy offices in expensive real estate markets and have come to rely on blockbuster publishing stunts and short-term insanity like variant covers to artificially boost sales numbers to keep their quarterly earnings looking for their parent companies?”

Good questions to ask, for sure, but questions that have become much more marked in the time of COVID-19. As the US and the UK headed in national lockdown, it swiftly became clear that Diamond’s monopoly would bite the comics industry where it hurts the most: the cash nexus. How would readers obtain their comics? Would there be a wholesale shift to digital publication, a strategy that would leave retailers with no product to sell? Writing for The Daily Beast, Asher Albein suggests that the industry faces an existential crisis that they have never seen before:

“World War II couldn’t do it. An industry crash in the 1990s couldn’t do it. Now, for the first time in the history of the medium, monthly comics are grinding to a halt due to the novel coronavirus pandemic […] last month, Diamond Comics Distributors—the monopoly that supplies monthly comics to reatilers in the United States and Britain—announced that it was refusing to accept new product from comics’ largest publishers, including Marvel, DC, Image, and Boom Studios. ‘Product distributed by Diamond and slated for an on-sale date of April 1stor later will not be shipped to retailers until further notice,’ Diamond chairman and CEO Steve Geppi said in a statement. ‘Our freight networks are feeling the strain and already experiencing delays, while our distribution centers in New York, California, and Pennsylvania were all closed late last week,’ Geppi’s statement continued. ‘Our home office in Maryland instituted a work from home policy, and experts say that we can expect further closures. Therefore my only logical conclusion is to cease the distribution of new weekly product until there is greater clarity on the progress made toward stemming the spread of this disease’”.

On the one hand, Geppi is right to heed the advice of medical experts (I’m looking at you Messrs Trump and Johnson). Yet on the other, the fact that Diamond remain in situ as the only distributor in operation for an entire industry demonstrates how troublesome the current model is. Of course, even with more competition and more distributors, the situation would surely be the same. COVID-19 doesn’t discriminate between business models, regardless of monopolistic practices. But like many of our infrastructures—political, cultural, medical, as well as economic—the pandemic is running riot, burning through whatever foundations exist, cutting down the best laid plans of mice, men and corporate chiefs—although to be blunt, there doesn’t appear to have been any contingency plans whatsoever, best laid or otherwise (I’m still looking at you Trump and Johnson). Yes, the pandemic has caught everyone off guard, granted, but did our governments and corporations believe that market-forces would protect us all from the anarchy of nature? It would appear so on the strength of evidence.

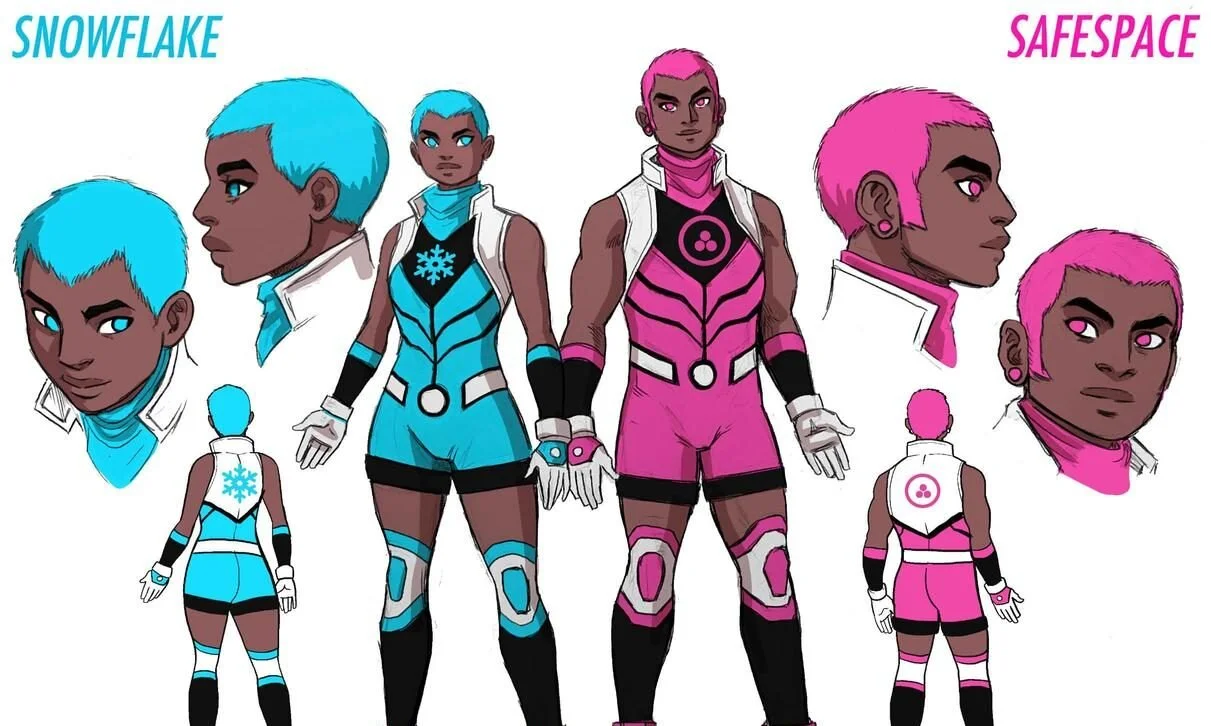

It wouldn’t be the digital age without a few bare-knuckle scrapes on social media between creators and fans, some of whom have been mocking new series, Marvel’s New Warriors (which, to be honest, I initially thought was a parody comic, but as it turns out, it’s a superhero title for the woke generation, complete with characters called Snowflake and Safespace). To be sure, I’m glad Marvel are thinking of ways to diversify its character population further, but this is so on-the-nose that, as I said, it seems like a piss-take.

But it is interesting that some comics creators on social media have been claiming that that the industry has been through downturns like this in the past as the medium has historically cycled through boom and bust periods at certain junctures. I would argue, however, that the industry has not faced a crisis of this magnitude before (and that includes Crisis on Infinite Earths, Zero Hour: Crisis in Time, Infinite Crisis, Identity Crisis, Final Crisis, Heroes in Crisis, and all the rest of the crises that are don’t have Crisis in the title). Although superheroes remain the dominant genre, comic books belong to a much broader medium, and in the 1950s, the biggest seller was not superheroes, but Dell’s Disney comics. More than this, the comic book market is not as stable as it once was nor has it been for over twenty years, perhaps even longer. More egregiously, Diamond released news about the distribution pause not by contacting retailers first and foremost, but by apparently leaking it to Bleeding Cool. Owner of Grumpy Old Man’s Comics in Seattle, Alan LaMont, said that:

“For Diamond to leak this out to Bleeding Cool and other news outlets without first contacting the retailers is highly irresponsible and shows the overall lack of respect Diamond has towards its retailers in general, if in fact they did.”

Whether or not this is accurate is difficult to ascertain, but other retailers have repeatedly said that communication between Diamond, and the big two, DC and Marvel, such as Ryan Seymour of Comic Town in Columbus, Ohio, who explained that:

“The lack of transparency and candor from Diamond and the big two really is mind-boggling. This change could be a result of their chosen printer companies closing down. Maybe it is a financial thing, where Diamond cannot cover their expenses or that publishers are not extending any credit?”

While I first shrugged off the idea that a corporate monolith like Diamond may be struggling in economic terms, news emerged on 13thApril that the company would be furloughing some of its staff:

"As you know, COVID-19 is having a dramatic impact on businesses around the globe and unfortunately, Diamond is no exception. As a result, we have made the difficult decision to furlough some employees. This was not a decision we made lightly, and we only do so to protect our company's financial future and preserve jobs. We have taken several steps already to mitigate our financial exposure including delaying payment to publishers, extending vendor payment terms and significantly reducing executive compensation. It is our goal that, on the other side of this crisis, our furloughed employees will return to their roles."

I can’t help but think that a company as large and profitable as Diamond could weather the current crisis, but I won’t pretend to be an expert in economic mathematics nor business studies. But it seems to be as clear-as-crystal that the people who will suffer the most during the pandemic are the workers, not the executives. I would also add that Diamond may indeed enjoy a monopoly regardless of the decision of the US Department of Justice, but the companies and creators have a role to play too. I guess we’ll have to wait and see how things turn out, but more and more people seem to be watching the watchmen nowadays.

Even as I write this, the situation is changing. DC have announced that they’ll be shipping new comics soon via other distributors, perhaps firing the first warning shots in the ‘Crisis on Distribution War's’ Event coming soon.

Over a number of instalments, four of us will be discussing the Direct Market, the impact of the pandemic on the comics industry, possible solutions and contingencies, as well as what the future may hold the current distribution system post-Crisis (he says optimistically). We’ll also be getting into the differences between the US and UK distribution models as, perhaps surprising to many, most UK comics continue to be published during the lockdown. Join Todd Allen, Shawna Kidman, Philip Vaughan and myself to find out why!

We’re watching the watchmen too.

Dr William Proctor is Principal Lecturer in Comics, Film & Transmedia at Bournemouth University, UK. He has published on an assortment of topics related to popular culture, and is the co-editor on Transmedia Earth: Global Convergence Cultures (with Dr Matthew Freeman, 2018 for Routledge), and the award-winning Disney’s Star Wars: Forces of Production, Promotion and Reception (with Dr Richard McCulloch, 2019 for University of Iowa Press)).