Tracing Scottish Comics History (1 of 3) by Chris Murray

/I’m fascinated by Scottish comics. This should come as no surprise. I was born and raised in Dundee, the home of DC Thomson, publisher of The Dandy and The Beano, and countless others. The indie Scottish comics scene is vibrant, and Scotland can boast of industry legends like Grant Morrison, Frank Quitely, Mark Millar, Alan Grant, Cam Kennedy, Eddie Campbell, Ian Kennedy… the list goes on and on. Also, I teach and research comics at the University of Dundee, which provides many wonderful opportunities to meet and collaborate with the wealth of Scottish comics talent, and through our classes, and initiatives like Dundee Comics Creative Space and Ink Pot studio, to help support the next generation of comics creators and scholars. But the thing that really fascinates me is the all but forgotten history of Scottish comics.

Comics publisher and historian John McShane has made a case for the Glasgow Looking Glass (1825) as the world’s first comic, and whether or not that holds true, he has certainly put this long overlooked periodical back on the map (Fig. 1).[1] Likewise, over the last several years I have been keen to shine a light on some neglected corners of Scottish comics history, researching the smaller comics publishers, and particularly, trying to trace some of the actual locations of defunct publishers, printers and studios. There is an element of detective work here, which is hugely enjoyable, but there’s also frustration that comes from the fact that some of this information is extremely hard to come by, however, a story is slowly starting to emerge about Scottish comics publishing beyond the well-known story of DC Thomson. Apart from the Glasgow Looking Glass there were many illustrated magazines employing cartoonists, especially in Dundee and Glasgow, in the nineteenth century and well into the early part of the twentieth century. Also, several small Scottish publishers emerged in the 1930s and 40s, such as Glasgow’s Cartoon Arts Productions, Foldes Press, which was initially based in Edinburgh before being bought by Manchester-based World Distributors Ltd, and Dundee’s Valentine & Sons. A considerable volume of comics emerged from these publishers, in addition to the huge output of DC Thomson, who had an in-house comic art department, but also utilised an extensive network of freelancers. Moreover, this industry was supported by a number of private art studios. The Scottish comics industry is more varied and complex than has been appreciated, and this creative economy has not yet been properly mapped or understood. Here I would like to outline some of these aspects of this industry, and the physical traces that it has left behind.

Fig. 1 Glasgow Looking Glass, Vol. 1, No.1 (John Watson, June 11th 1825).

Livingstone and Strathmore Studios (Dundee) and Mallard Features (Glasgow)

The brothers Jock and William (Bill) McCail came to Dundee from Hartlepool to work for DCT in the 1920s, but fell out of favour for political reasons and went to work for Amalgamated Press and Swan in London the 1930s and 1940s. The McCail’s also set up art studios in Dundee and Glasgow in the 1940s, which were mainly run by Bill, and the Dundee studios were co-run with Len Fullerton. The Dundee workshop was established in 1942 and was initially called Livingstone Studios, but then became Strathmore Studios, and was located in the High Street. It then moved to nearby Commercial Street. The Glasgow workshop was called Mallard Features Studios and Bill used it to combine his interests in comics and nature illustration, and particularly horses, for which he was well-known. This was seen in The Round-Up (1948), a superhero/cowboy mash-up starring Quicksilver, The Wonderman of the West, which was produced for the Children’s Press in Glasgow (Fig. 2).[1] These studios were instrumental in supporting freelance work in Scottish comics, and gave several artists crucial training.

Fig. 2: The Round Up by William McCail (Mallard Features/The Children’s Press, Glasgow, 1948)

The McCail studio in Dundee High Street was based in a building, now demolished, that was famously the headquarters of General Monck when he laid siege to the city in 1651. This building was demolished in the 1960s when the Overate area of the city centre was being remodelled (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3: Centre-Left, The building known as Monck’s Headquarters in the Overgate area of the city centre.

The studio was home to comics artists who were based at the McCail studios included Len Fullteron, a comics artists who, like Bill McCail, was also a celebrated nature artist; Sydney Jordan, a Dundonian who went on to create the popular science fiction newspaper strip Jeff Hawke; Sam Fair, a Dundonian artist who had contributed to The Dandy in the early years and throughout the war; and Colin Andrew, another Dundonian who worked as a junior artist in the Dundee studio at a young age and then went on to work for King-Ganteaume studios, producing art for Len Miller and Son, and then later working on The Eagle and TV Century 21 in the 1960s. Though the building is long gone, a ghostly trace of it remains. The statue of Desperate Dan now strides purposefully through the city centre, and towards the shopping centre where the building once stood, now the site of a Primark store (Fig. 4). The beloved Desperate Dan statue, designed by artists Tony and Susie Morrow, has become an iconic part of the city. It is commonplace to see tourist posing for photographs, and comics students also always pose with Dan at Graduation. The University Chancellor may officially confer all the degrees with a pat on the head from the University cap, but Comics Studies students only really graduate once Dan has done his part, doffing them on the head with a rolled up copy of The Dandy (Fig. 5 and 6). Also, upon hearing that The Dandy would cease publication I had to console Dan, or more properly, he consoled me (Fig. 7).

Fig. 4: Desperate Dan and Primark, High Street, Dundee, 2019.

Fig. 5: Comics students graduate at Desperate Dan statue, 2016.

Fig. 6: Comics student Megan Sinclair being graduated by Dan, 2015.

Fig. 7: Dan consoles Chris as The Dandy ceases publication in 2012.

The Desperate Dan statue is also sited very close to New Inn Entry, where the illustrated periodical, The City Echo, was published in 1907, in the tradition of the Piper O’ Dundee and The Wasp, late nineteenth century periodicals which featured many cartoons and comics artists. This is also short walk away from Meadowside, which is dominated by the DC Thomson building, often referred to as ‘Thomson Tower’, or ‘The Fun Factory’ (Fig. 8). Also nearby is the old Leng building, which housed the John Leng and Co, Ltd, the great rival of DC Thomson before the companies merged (Fig. 9). Leng employed the first cartoonist contracted to a newspaper, Martin Anderson.[1] I walk past these places on an almost daily basis, and can feel the history of Dundee’s comics. This extends from the celebrated and still thriving comics publishing industry based in the city to the all but forgotten and lost places associated with comics production. It is notable that DC Thomson has long maintained offices in London, and re the only publisher still located on Fleet Steet, which was once the heard of the publishing industry (Fig. 10). I confess that the thrill of finding and researching these places has given me something of a bug for finding more places associated with comics history. And there was yet more Dundee comics history to uncover.

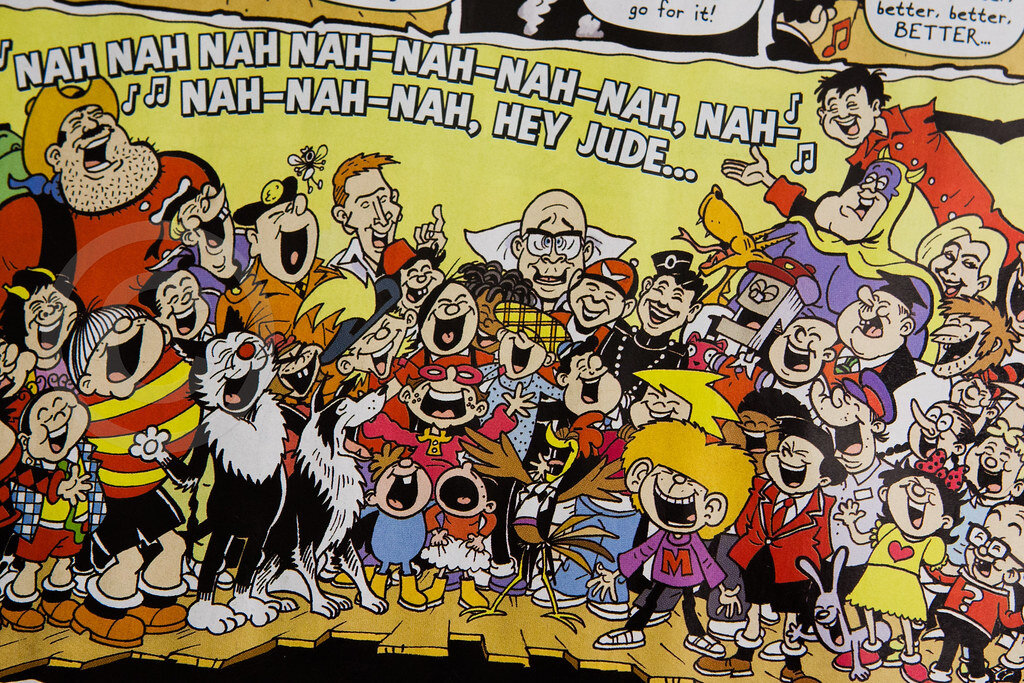

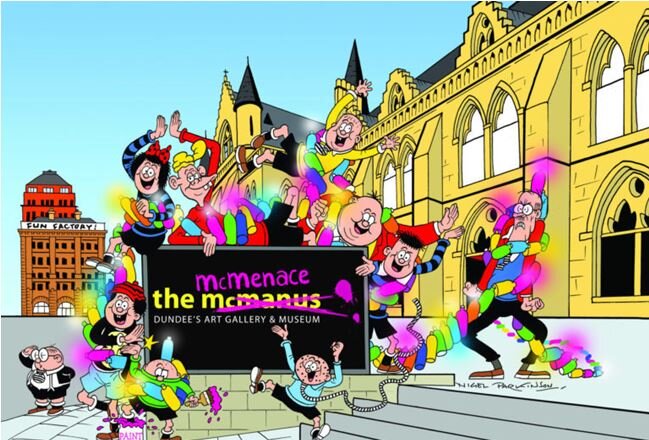

Fig. 8: DC Thomson’s ‘Fun Factory’ at Meadowside, Dundee, and McMenace exhibition at McManus Art Gallery and Museum, artwork by Nigel Parkinson, 2018. Copyright DC Thomson.

Fig. 9: John Leng and Co Ltd, Bank Street, Dundee.

Fig. 10 DC Thomson offices on Fleet Street, London.

Notes

[1] Matthew Jarron, Independent and Individualist: Art in Dundee 1867-1924 (Dundee: Abertay Historical Society, 2015), p.125.

[2] Chris Murray, The British Superhero (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2017).

[3] John McShane, ‘Through a Glass, Darkly: A Revisionist History of Comics’, in The Drouth #23 (Glasgow: The Scottish Arts Council, 2007).

Bio

Professor Christopher Murray is Chair of Comics Studies at the University of Dundee. He runs the MLitt in Comics and Graphic Novels (https://www.dundee.ac.uk/postgraduate/comics-graphic-novels-mlitt) and co-edits Studies in Comics (https://www.intellectbooks.com/studies-in-comics). He researches British Comics, and is author of The British Superhero (University Press of Mississippi, 2017) and Comicsopolis – A History of Comics in Dundee (Abertay Historical Society, 2020). Murray is director of The Scottish Centre for Comics Studies and Dundee Comics Creative Space, and is editor if UniVerse Comics. He has written several comics, including a number of public information comics on healthcare and science communication themes.

The ‘Remembering UK Comics’ series is curated and edited by William Proctor and Julia Round.