What Science Fiction Media Gets Wrong About Facial Recognition

/This is the final in a series of blog posts created by students in my PhD seminar on Public Intellectuals. I hope you have enjoyed the range of new voices and perspectives this series brought to this space.

What Science Fiction Media Gets Wrong About Facial Recognition

by Mehitabel Glenhaber

If you’re a theater-goer in the 21st century, you know how the AI surveillance dystopia story goes. The government has robotic eyes everywhere, tracking your every move with security cameras, and drones. Nothing escapes the watchful gaze of an computer system, which monitors your identity with face recognition and retina scans. Shady government agents sit in control rooms full of shiny blue screens, vigilantly watching thousands of video feeds. Tom Cruise, probably, is a fugitive on the run, but all the odds are against him.

Every day, it seems that our world gets a little closer to this dystopia that we see so often on the screen. Police departments all around the US have deals with clearview.ai, a startup that sells face recognition software trained on personal photos posted to social media. HireVue hucksters face-recognition algorithms to help companies decide who to hire, based on whose face a computer thinks looks trustworthy. Software companies and computer science labs try to convince us that computer systems can determine someone’s health, emotional status, or even sexual orientation, just from one picture of them.

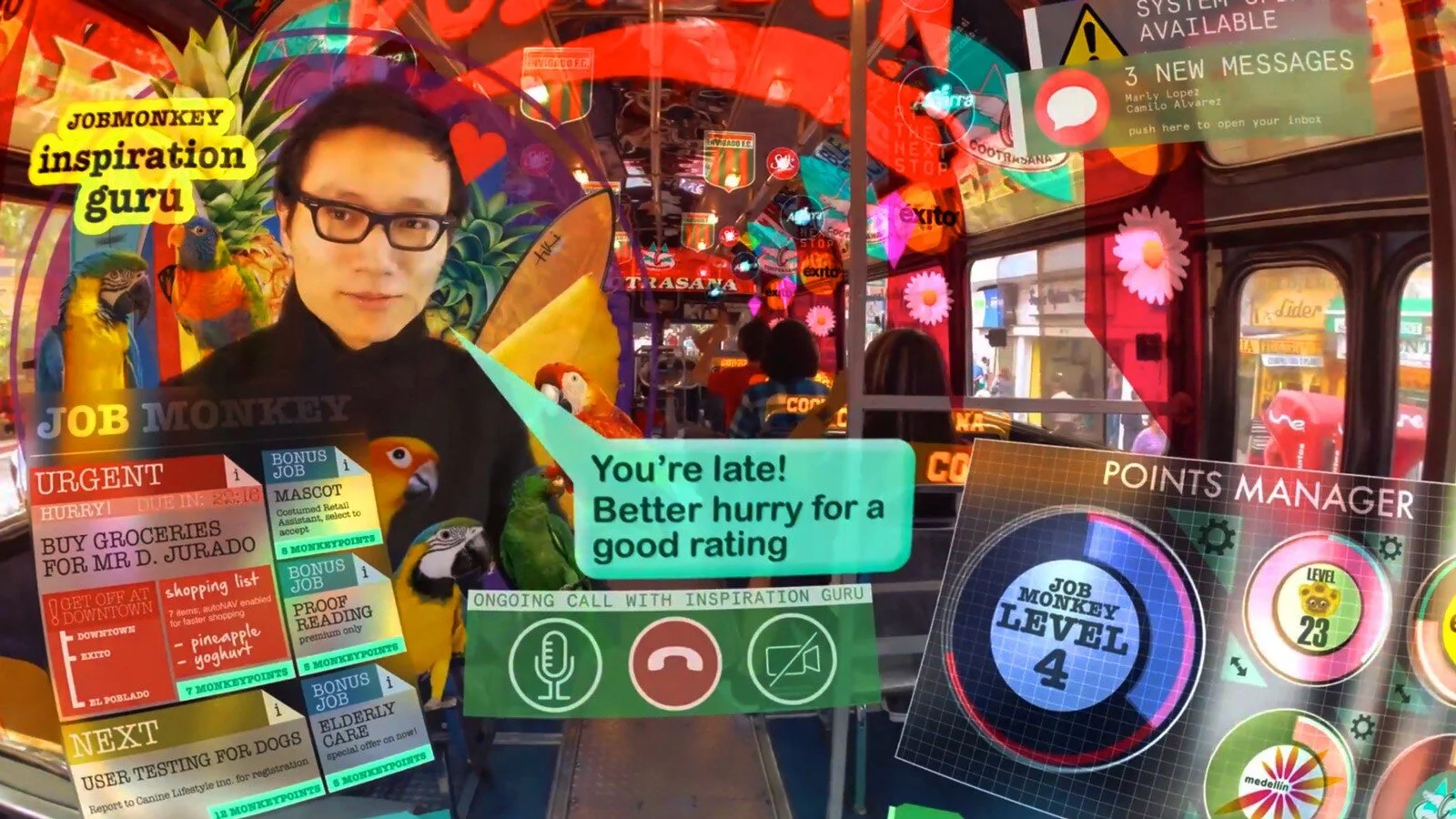

In fact, in the past couple years, we’ve seen an explosion of articles comparing the current state of tech to famous sci-fi dystopias: 1984, Minority Report, Blade Runner, Terminator, and Robocop. This makes sense, because sci-fi can be a useful tool for making sense of the role of technology in our society and understanding the risks and stakes of AI based surveillance systems. Sci-fi can predict, or even influence the development of real-world tech. For instance, when face recognition technology showed up in the James Bond film A View To Kill in 1985, Robert Wallace, the then Director of Technical Services Staff at the CIA, claims to have gotten a phone call from the higher-ups asking “do you have one of those?” and then “How long will it take you to make it?” An acquaintance of mine who works at a tech startup in San Francisco once told me a story about their office screening the dystopian film Hyper-Reality. The next day, they got a message from their boss which read “I wonder if we can turn this nightmarish vision into a fun reality! :)” When real-world tech developers are treating dystopias as inspiration boards, maybe it’s not crazy to try and use these films to understand where the world is headed.

Keiichi Matsuda’s nightmarish vision in Hyper-Reality, which I hope doesn’t become any kind of reality

But dystopian sci-fi can also mislead us about the future, or put our fears in the wrong places. Sci-fi narratives produced by Hollywood often give us a narrow picture: they show us only one set of dystopian tropes, and explore how members of only particular groups might be affected. In my own research, I look at depictions of facial recognition in science fiction film. There’s a lot of things that these films got right about the reality we live in now: Facial recognition everywhere is a huge violation of privacy. AI systems are scary because they’re inhumanly rigid, and they don’t care about you personally. Facial recognition is becoming a frightening tool for oppressive governments. But there’s also a few big things that these films get wrong – ways the tropes in these films don’t capture the whole picture. So let’s go into a few of them!

Yes! Even the Pixar film Coco has face recognition in it!

#1 – Who owns facial recognition?

When facial recognition in sci-fi films is used by humans, and not autonomous robots, it’s almost always used by a totalitarian, oppressive government that and uses it to surveill its citizens. Whether it’s John Anderton in Minority Reporttrying to hide from the precognitive police without his retina print giving him away, or Robocop using his cyborg memory to identify mugshots of a suspect, it’s usually government law enforcement using the technology in these films.

Government control of face recognition is very real concern in the world today! A lot of the people we see adopting facial recognition are official law enforcement officials: it’s now used by the TSA in airports, in local police departments, and by ICE to hunt down and deport undocumented immigrants. But a lot of what makes facial recognition so frightening in the real world, that these films often leave out, is that facial recognition software is produced by privately owned companies. These companies are getting rich off of government surveillance – in the article I linked above, for instance, ICE payed clearview.ai $224,000 dollars for their services. Being privately owned also means that, even when these companies sell their services to the government, their software is proprietary – it’s often a secret black box that even government agencies can’t take a peek inside. While sci-fi films prepared us well to imagine a world where facial recognition is used by a restrictive government to oppress the population, we also have to be prepared for the opposite possibility: that corporations are playing fast and loose with this technology, with a dangerous lack of regulation.

To it’s credit, Robocop does actually get into some of what is so scary about private contractors selling tech to law enforcement – that it lets private corporations decide who laws get enforced on, and who they don’t.

#2 – What is facial recognition being used for?

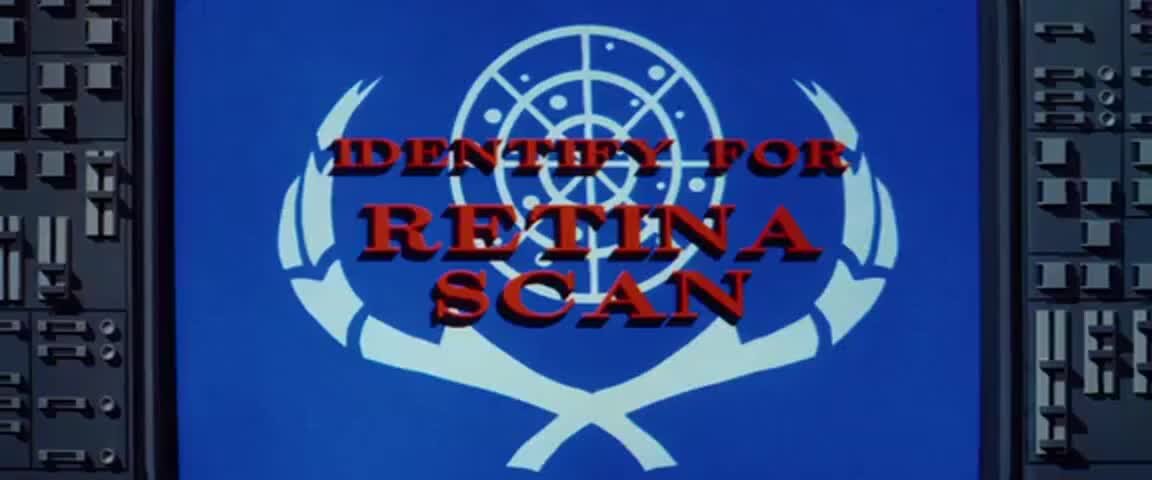

In Hollywood films, facial recognition is almost always being used to identify individuals, for security purposes. Sometimes the technology is part of a high-tech, retina-scan activated lock, like we’ve seen in Star Trek: Wrath of Khanor The Avengers franchise. Or sometimes it’s part of a sinister omnipresent surveillance network. In all these cases though, the point of facial recognition is to use an image of one person’s face to confirm that person’s identity. You’ve gotta admit, a camera zooming in and sketching a red box around a character’s face or eyeball, and their name rolling in monospace ticker tape on the screen is a great visual. But this one particular use-case doesn’t cover all the ways that facial recognition is being used today. We don’t see uses of facial recognition that happen on the secret back-end of websites, or in research labs.

Captain Kirk accessing top-secret information with a retina scan in The Wrath Of Khan (1982) was a genre establishing scene which wowed many fans in the 1980s and established the trope of facial recognition being used on high-tech safes.

Most patents for facial recognition these days aren’t actually about identifying individuals or creating security systems, they’re about using facial recognition to classify people: letting AI use faces to decide who’s a good hire and who isn’t, who’s a criminal and who isn’t. A group of computer scientists in 2017 even created a facial recognition algorithm which can supposedly identify if someone is gay or not – just based on their face. Facial recognition systems are also used to classify and judge behavior. Recently, there’s been a lot of controversy around remote proctoring softwares like Proctorio and ProctorU, which schools have been requiring students to subject themselves to in order to take remote tests during the covid-19 pandemic. And the Tokyo metro even uses a facial recognition system to grade employees smiles.

Facial recognition is also integrated into a variety of other places: when Twitter crops the previews of photos your post, when snapchat filters put bunny ears on your face, when deepfakes algorithms replace a face in a video with another face. If we only focus on the narrow view of facial recognition used a system to identify individuals, we risk missing the full breadth of ways this technology is used, and the possible benefits or dangers associated with each of those uses. While films might give us the sense that facial recognition is easy to define and ban, the reality is that the boundaries of this technology are not clear, and it’s a more complicated question.

#3 - How accurate is facial recognition?

On the silver screen, the scary thing about facial recognition technology, and AI in general, is that they are inescapably accurate. The Terminator, in Judgment Day (2009), is terrifying because he’s coming to get you, there’s no way to fool him – his robot eyes can identify you from half a mile away. In films about facial recognition, we never see the AI mess up – or, when it does, it’s only because characters went to extreme lengths to avoid it. In Minority Report, the only way that John Anderton can avoid being identified by a futuristic retina-scanning system is to literally remove his own eyeballs.

You can run, but you can’t hide.

However, when I read what technology studies scholars are writing about facial recognition, the thing that really scares me about it is that it messes up all the time. As Joy Buolamwini’s work shows, face recognition systems are actually terrible at telling black people apart. Some facial recognition systems don’t even recognize black faces as faces. Os Keyeshas also written about how facial recognition systems have no idea how to deal with queer and trans people, and constantly misgender them. Facial recognition systems are only as good as the data they’re trained on – and if mostly cis white male programmers use their own faces to test these systems, we end up with systems which are awful at identifying everyone else.

Like all AI systems, facial recognition systems can encode the biases of their creators. We already know that AI systems for filtering through candidate’s resumes discriminate against female candidates and people of color. And we already know that predictive policing algorithms perpetuate bias against black and latinx folks. So we shouldn’t expect facial recognition systems to be any better. The remote proctoring softwares I mentioned above have already created problems for neuroatypical students with autism or ADHD, or even women with long hair, since it interprets these student’s natural tics as cheating behaviors. Films about facial recognition are certainly right that AI systems are frighteningly inflexible – there’s no way to reason with them, and they can’t be sympathetic to your personal situation. But instead of worrying about our lives being governed by deadly accurate machines, maybe we should be more worried about the alternative dystopia where these systems are wrong all the time, but we continue to put faith in them.

#4 – Who is the target of facial recognition?

Seriously? This movie’s supposed to be set in Washington DC?? A city that is currently 45.5% black??

In Hollywood surveillance dystopia films, the lone rebel protagonist on the run from an oppressive government is almost always a straight white man. This is not particularly unusual or unexpected – most Hollywood studio executives are straight white men, and they tend to make movies about straight white men. But in addition to just being bad representation, films which only tell this kind of story perpetuate an unfortunate trend in surveillance studies of straight white men only caring about surveillance when they can see themselves as the victims of it.

Surveillance studies has, historically, not talked about race – which is pretty inexcusable, given that race is such a big factor in who gets surveilled. Influential writers in surveillance studies have often been white men, and have often regarded surveillance dystopias such as “the panopticon” or 1984 as a hypothetical scary future which might affect them. But something that they’ve ignored is that the kind of constant scrutiny, judgment, and oppression which are 1984 or Minority Report to white men are just current lived realities for people of color. People of color are already watched in stores, and have credit score checks run on them all the time. They are hassled by the police constantly, and are murdered by cops at a much higher rate than white people. Queer folks, also, especially queer and trans people of color, constantly have their gender presentation scrutinized, and judged, and are also often the subjects of police violence. As Brian Merchant writes, dystopian literature can “allo[w] white viewers to cosplay as the oppressed, without actually interrogating in any meaningful way what oppression might actually entail or who gets oppressed and why.”

Given everything I’ve said in the last section about how algorithms in general discriminate against black people, women, and queer folks, how facial recognition systems already fail when it comes to these groups, we should be very worried about what wider adoption of facial recognition technologies is going to mean for these groups in particular. But we don’t see them being subject to facial recognition technology in movies. I can’t think of any films where an algorithm falsely identifies a black person as a criminal or denies a trans character access to healthcare. But in the real world, if we’re headed towards a surveillance dystopia, straight white men probably won’t be the main victims of it.

A comment I get a lot from my (often relatively privileged) friends when I try to warn them about the dangers of face recognition and surveillance is “sure, it sounds bad, but I guess I just don’t care that much about my own data, it doesn’t personally creep me out to know the government’s spying on me.” This individualistic view of data privacy makes a lot of sense in a world where movies tell you that the main thing that’d be scary about surveillance is if you personally had to go on the run from a surveillance state. But if you’re reading this, especially if you’re a straight white man, I want to say to you: don’t be scared of facial recognition collecting data on you because of what it’s going to do to you. Be scared of it collecting data on you because of how that data’s going to be used against your queer, black, or latinx neighbors.

As I said before, sci-fi can be a useful tool for envisioning and understanding how new technologies might affect our society. These films are completely correct that face recognition systems can be worryingly cold and inflexible, and can be employed by governments as tools of oppression. But images from these films might also blind us to another possible dystopia we could be headed towards: one where we put extreme faith in corporations which make huge amounts of money employing faulty and biased algorithms which discriminate against people of color, women, and trans people in all sectors of society. I don’t know exactly what a film which captured all these complexities of the problem would look like – though I’m still holding out for the 21st century north-by-northwest-esque thriller about a person who has to go on the run after they’re mis-classified as a Most Wanted criminal by a facial recognition algorithm. But until films like this exist, we need to think about how these existing films might create blind spots for us, even as they warn us about dystopia.