Endings, Beginnings, Transitions: Star Wars in the Disney Era (Part 2 of 3) by Will Brooker and William Proctor

/Proctor

What are your thoughts on TROS, and the Disney-era of Star Wars more generally?

Brooker

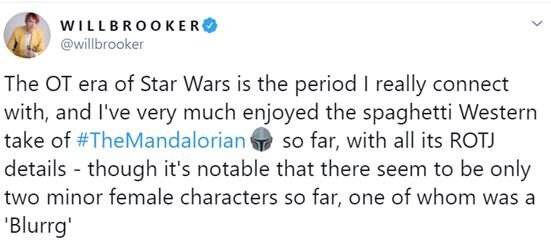

First, I should note that I hadn’t seen Anita Sarkeesian’s tweet about The Mandalorian, but I made what seems a very similar observation myself after watching the first episode in November.

I don’t think quantitative approaches to popular culture give us the full picture -- a movie that stars almost entirely women, in which female voices are heard far more often than men, could still be misogynistic -- but I feel they can provide a useful starting point for further discussion. The Bechdel Test was surely never intended as a serious analytical tool, but it nevertheless prompts valuable debate. Since the first episode, The Mandalorian has introduced more female characters, most notably former shocktrooper Cara Dune, played by former MMA fighter Gina Carano. I would personally find it more interesting to consider the fact that Gina Carano is clearly a very strong woman, with visible muscle and broad shoulders, and the way her physicality disrupts the conventional representations of women’s bodies that we see in, for instance, the Marvel Cinematic Universe, where even the ‘strong’ superheroines like Captain Marvel and Black Widow tend to be more toned and slim than Carano. So to my mind, it is worth asking what role women play in the narrative, what they say, how they look and what relationship they have to other characters, rather than just how many there are of them. But I’m certain Anita Sarkeesian would agree that adding up numbers and presenting the total is a way to make a clear and striking initial point, rather than a final argument. Far too much has been made of her tweet, I suggest, which she says she wrote when she was tired, and in which she asked a question rather than making a statement. Note that I didn’t get thousands of abusive replies to my tweet saying almost exactly the same thing, and that isn’t just because she has many more followers than me.

As for The Rise of Skywalker, I hardly know where to start. I saw it twice during the opening week and it’s the most disappointing Star Wars movie I have experienced since The Phantom Menace twenty years ago. Despite its poor critical reception, there seems an overall consensus that it was trying to provide ‘fan service’, which to me prompts the question: which fans is this movie serving?

To an extent, there are rewards for fans who like the Original Trilogy best; a glimpse of Bespin, the return of Palpatine and Lando (and Solo), and Chewbacca’s long-awaited medal. And I can understand the argument that J.J. Abrams was trying to -- misguidedly, in my opinion -- appease the vocal minority who complained about Rose Tico, by marginalising her character so dramatically in this movie. I’ve seen the movie satirised as ‘Written and Directed By Reddit’, implying, I think, that it met the demands of white, straight, conservative fanboys.

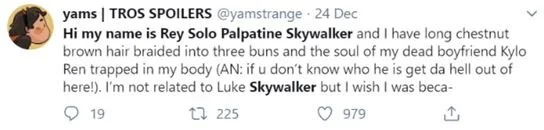

On the other hand, while it does seem that Abrams deliberately rejected key characters, ideas and narrative prompts -- such as Rey’s parents being ‘nobodies’ -- set up by Rian Johnson in The Last Jedi, he also continued the love-hate dynamic between Rey and Kylo Ren that was only really established in the previous episode, and made use of the flexible Force powers such as the telepathic FaceTime that had played such a role in their troubled romance under Johnson’s direction. Another popular online satire implies, in contrast to the ‘directed by Reddit’ image, that The Rise of Skywalker is fanfic in the mould of the notoriously bad Harry Potter story ‘My Immortal’, and presumably aimed mostly at teenage girls.

So I think critics have a tendency to use the term ‘fans’ without considering that there are many, many conflicting factions of Star Wars fandom -- there have been at least since The Phantom Menace, which I documented back in the day, and no doubt the divisions and debates go back to the late 1970s, though they would be a lot harder to track prior to the internet. It’s equally lazy -- I agree with you here -- for journalists and other commentators to claim that negative response to The Last Jedi was primarily due to racist, sexist fans who disliked the focus on characters like Rose; while I don’t agree with your suggestion that people with bigoted views can be dismissed simply as ‘trolls’’, which implies mischievous provocation for the sake of it, I think there were, again, multiple groups of viewers who were disappointed with Rian Johnson’s film for various and diverse reasons.

Anyway, my objections to The Last Skywalker were primarily due to what I saw as its inconsistency, lack of logic and the gaping, glaring plot holes, which shattered my engagement and enjoyment. It’s telling that there are so many lists of questions about this movie online, some of them presenting a hundred issues: they overlap, but each list finds different problems to raise. It would be tedious for me to present all of my own, but they start right with the opening crawl and continue to the last shot. Why would Palpatine send out a taunting message about his return if his new fleet is a secret which it takes elite agents and spies to uncover, in the film’s second scene? (And why are we being told in text about such a massive upheaval to the galaxy, the titular ‘star wars’ and the ongoing storyline, which has apparently shifted onto an entirely different track since the end of the previous episode?) How are we supposed to know that the opening sequence of Ren defeating a small army of extras was set on Mustafar, and that his opponents were Vader cultists? The information was only given in surrounding paratexts, rather than as part of the film itself. Why, for that matter, would Vader have kept a ‘Wayfinder’ to the Sith planet Exogol in the wilderness of Mustafar, and what was the agenda of the cultists: to protect it for eternity? In that second scene, why does Poe argue with Rey that she should have been on the mission with them to recover information from the Imperial spy? He’s supposedly the Resistance’s best pilot, and he had Finn as a gunner; there was no hand to hand combat or Force ability involved, so why would a Jedi have been of more use on the ship than training back at the base? Jumping ahead, why would the address of the second Wayfinder have been inscribed on a Sith dagger decades ago, and how could its hilt be reliably used as a guide to the precise location of the Wayfinder on the wreck of the Death Star? Why do Poe’s companions react with such scandalised shock to his past as a spice runner, when it’s a carbon copy of Han Solo’s history, and they treated him with awed respect in The Force Awakens? How do Rey and Kylo’s telepathic communications allow them to see each other and touch objects around the other person, but not to detect their location? When they fight, with Kylo on Kijimi and Rey on the Imperial craft, would they each look, to an observer, as if they’re ducking, dodging and swinging sabers alone? I’m happy for films to portray uncanny powers, but I think there must be some rules and logic even to magic, or it becomes a hand-waving, anything-goes free for all.

And skipping all my objections about Palpatine family history, why would it would be appropriate in the final scene for Rey to pay tribute to the Skywalkers on Tatooine? Luke was deeply unhappy there and couldn’t wait to leave. Anakin was a slave who witnessed the murder of his mother there; his violent revenge was part of his turn to the Dark Side. Leia’s only time on Tatooine was spent as the prisoner of Jabba the Hutt. Why, lastly, is the Lars homestead so pristine, like a heritage site? When we last saw it, it was scorched by a Stormtrooper raid, apparently half destroyed. I like nostalgic callbacks, but they must make some sense.

It is possible that a third or fourth viewing would clear up some of these puzzles for me. It is very likely that Abrams could explain his intention in interviews, the way he did with the mystery about what Finn wanted to tell Rey during the entire movie. I don’t doubt that the Star Wars Visual Dictionary would fill in the details for me, the way it does with the minor character Beaumont Kin, apparently a professor in the Star Wars universe and an expert in Sith History. And I expect some spin-off novel, or comic, or Disney+ series, will come along to justify or retcon the more glaring errors.

But I don’t think I should really have to see a space fantasy blockbuster movie more than twice to make sense of it and be satisfied by its plot and characterisation, and I certainly don’t think I should have to read a Visual Dictionary or a spin-off novel, or watch another TV show, or seek out interviews with the director, to get the full picture. I think that’s a sign of a bad movie, frankly. Because I was so regularly jolted out of the film, I found it very hard to become invested in the heroes and their missions, which involved a complicated and mostly-pointless series of secondary missions and fetch quests; so while they kept insisting earnestly to each other that this was their last chance, this was what they’d been fighting for, this was the one shot they couldn’t fail and so on, none of the emotion felt properly earned to me, and the flat, expository dialogue didn’t help. My only real enjoyment came from the performance of Adam Driver, who I think transcended the material -- his incorporation of Han Solo mannerisms in his final, almost silent scenes was remarkable -- and is leagues above almost everyone else in the cast.

So overall, while I’m glad a new generation has clearly gained a great deal of pleasure from the sequels, and I’ve enjoyed the world-building, spectacle and adventure to an extent, I am starting to secretly wonder if it would have been better to leave the Star Wars movies as they were, before both prequels and sequels. That makes me sound very much like a nostalgic, veteran purist, or worse, conservative and reactionary, but it’s surely clear that neither of the trilogies produced since 1999 has been anything like as successful -- not commercially, but critically and I’d suggest, aesthetically.

The new film started me wondering, in fact, whether Star Wars has always been this bad; whether all the movies, right back to 1977, have nonsensical, convoluted plots that don’t make sense when you look twice at them, plus cheesy dialogue and poor acting. I’d have to revisit and reconsider them properly to make sure. I think the Original Trilogy is actually admirably simple and direct though from start to finish, though, and that it tends to avoid the faults of The Rise of Skywalker. As a final anecdote, I clicked on a clip recently, linked from someone’s tweet, and watched Leia explaining to Han that Luke is her brother, as Han reacts with surprise and relief: I was caught up immediately in the moment, and the performances seemed subtle and intelligent. And that’s a brief scene from my least favourite part of my least favourite movie in the Original Trilogy. I don’t think it’s just nostalgia and memories of my childhood that makes those movies work for me.

Proctor

Personally, I think the Bechdel Test is perfectly fine to spark conversations, especially in class-room situations, but as an academic methodology, it is not only useless, but emphatically absurd. It was never intended as a rigorous scholarly instrument, its origins coming from two-pages within a comic book (by Alice Bechdel, hence the name). I feel very strongly about this, as you can probably tell! There are many films that pass the ‘test’ that have been criticised for misogyny, from Fifty Shades of Grey to Charlie’s Angels (2001), while The Hurt Locker fails to meet the grade, even though it’s directed by Kathyrn Bigelow. Quantitative bean-counting of this nature tells us little to nothing, and I strongly believe it has no place in academic study.

I think you’re right about the original trilogy. It’s quite a simple story, which is not to say it’s simplistic, and in no way is it as convoluted nor as baffling as the recent sequels. I wonder if the state of blockbuster cinema these days is much more focused on spectacle than narrative, generally speaking. Although that accusation has been levelled at blockbusters since at least the 1970s, I can’t help thinking that films like Jaws, E.T, The Goonies,The Lost Boys, Ghostbusters, the Indiana Jones films, and others, were more successful as stories as well as SFX vehicles. Like you, I don’t think this is simply nostalgia for my childhood. The Rise of Skywalker is an example of bad storytelling, one albeit decorated superfluously with costly SFX, I’d argue. Character arcs are left dangling and incomplete. For all the positives that came with John Boyega’s Finn in The Force Awakens, he has almost zero character development in The Last Jedi and The Rise of Skywalker; and as you rightly point out, Kelly Sue Tran’s Rose Tico is unceremoniously sidelined for much of TROS, which has sparked a hashtag protest since the film’s theatrical release (#RoseTicoDeservedBetter). Moreover, calls for a Disney+ series focused on Rose are currently making the rounds on social media and in entertainment journalism.

I also saw TROS twice in as many days, and it will be my last, for all of the reasons you illustrate. It’s not worth repeating the same criticisms here, but I’d like to add that I was less cynical when the news surfaced that a new trilogy would be entering pre-production in 2012, that I am now. Overall, the sequel trilogy is at best a missed opportunity, and at worst, a flagrant disregard for the so-called Skywalker Saga. It undermines the victory in Return of the Jedi in many ways, and dilutes the tragedy of Anakin Skywalker. Not that I’m arguing that the prequels are ‘better,’ not by a long chalk. In fact, one of the reasons why I was ‘cautiously optimistic’, as with many Star Wars fans at the time—captured in an article I wrote for Participations—where I partly drew on your methodology in your Using the Force: Creativity, Community and Star Wars Fans—was precisely because George Lucas would no longer be involved, and that Disney would surely hire seasoned writers and directors to continue the story in a new, inventive way. It’s all very well having The Empire Strikes Back scribe Lawrence Kasdan return to co-write The Force Awakens, but as I said above, Abrams has proved that he’s not a good writer, even in collaboration. Hiring Chris Terrio to co-write TROS seems an odd choice to me, too. He hardly has an exceptional track record, having written Batman Vs Superman: Dawn of Justice, and the more risible Justice League movie (although to give Terrio his due, he also wrote Ben Affleck’s Argo, which was based on Tony Mendez’s The Master of Disguise).

So, I would argue that the sequel trilogy does not, as Disney disingenuously announced in promotional discourses for TROS, finally end the Skywalker Saga satisfactorily. It’s not as if Return of the Jedi left dangling plot threads: the Empire is defeated, Luke confronts Vader and the Emperor, and Vader sacrifices himself to save his son and bring balance to the force (as prophesied in the prequels). Palpatine being somehow ‘alive’ in TROS feels to me like a retcon too far (although it’s worth pointing out that the Star Wars Expanded Universe [EU] of novels and comics featured the Emperor returning as a clone in Dark Empire, so there is at least some precedent).

(For readers unfamiliar with transmedia Star Wars, the EU included stories told in the aftermath of Return of the Jedi, since Timothy Zahn’s Heir to the Empire was published in 1991, that is, before it was removed from all levels of canon by Lucasfilm in 2014 to clear the slate for the sequel trilogy.)

Indeed, Lucas himself claimed many times that the saga was now over. I realize that Lucas feels mistreated by Disney: he was meant to be the ‘keeper of the flame,’ and gave them detailed treatments of what would have been his sequel trilogy (which I admit doesn’t align with his comments about the saga being finite and complete, but Lucas has been a notorious editor of established history).

For that article, I interviewed fans and scholar fans, including Henry Jenkins, who said that:

The best news contained within the announcement may be that George Lucas himself is stepping back from direct control over the future of the franchise. After the first trilogy was created...he [Lucas] lost the capacity for self- censorship and thus put every idea that caught his fancy, good and bad, on the screen or elsewhere into the franchise. And as this happened, he became increasingly embattled with his fans, refusing to bow to popular pressure in any form, and reading it more or less as the same thing as pressure from the studios, that is, as a compromise to his own artistic vision...There could be no way forward for Star Wars as long as Lucas remained at the helm.

I also interviewed one Professor Will Brooker! Lucas is ‘a bad artist’ you stated, and ‘he shows bad artistic taste…it is a shame he has been allowed to exercise it so freely.’

I now wonder what the sequel trilogy would have been like if Lucas’ treatments weren’t discarded so quickly. Disney claimed that they wanted to produce something that tapped directly into the original trilogy’s aesthetic to address the prequel ‘bashers,’ while Lucas was all for expanding the imaginary world with something radically different. (Say what you will about the prequels, they certainly involved massive amounts of world-building, even if the story was not articulated as well as one would expect.) The Empire Strikes Back remains the firm favourite for many fans, but it was based on Lucas’ treatment, then written by Lawrence Kasdan and Leigh Brackett (and directed by Irwin Kershner). I can’t help but imagine that the sequel trilogy as outlined by Lucas, but written and directed by veteran creators, might have been more interesting and innovative than what Disney gave us. Viewing TFA, TLJ, and TROS as a unity— especially when joined with the original trilogy and the prequels—lacks narrative logic and causality, and jars with what has been established in Star Wars canon. Again, the lack of editorial governance and coordination has created an enormous narrative mess.

I did enjoy some elements of the sequel trilogy, nevertheless. As expected, the SFX are dazzling. I thought that The Force Awakens managed to successfully tap into the original trilogy's aesthetic, and it was exuberant and energetic, for the most part. I was completely on-board in fact until the moment when one of the rebels commented on Starkiller Base with, ‘it’s another Death Star,’ only for an image to demonstrate that the former is simply MUCH BIGGER than the latter (which works perhaps as a metaphor for the size-and-scope of blockbuster cinema in the 21st Century).

I enjoyed the more diverse cast, while also remembering that Lucasfilm would not be so progressively-minded if diversity didn’t sell, and that hiring ethnic minorities does not necessarily mean that representation is automatically serviced and box-ticked. I am indebted to Kristin Warner for her theory of ‘plastic representation,’ meaning ‘a combination of synthetic elements put together and shaped to look like meaningful imagery, but which can only approximate depth and substance because ultimately it is hollow and cannot survive close scrutiny.’ I would certainly argue that John Boyega’s Finn is an example of this ‘plastic representation,’ especially in TROS.

I also like Daisy Ridley’s Rey, but Adam Driver is by far the stand-out actor here. I was bothered when Rey kissed Kylo/ Ben once he resurrected her from the dead—I’m even irritated typing that—as it seemed ad hoc and without the necessary foreshadowing. Was that to appease Reylo fan shippers? And to address your point about fan service, which fans are being ‘serviced’ per se, as you ask? I can’t see that Disney would seek to appeal to the minor corpus of anti-PC, reactionary audiences—that’s an abysmal business model for blockbuster Hollywood to invoke, I’d argue. You can’t please all the people all of the time, as the adage goes, and there’s no way to satisfy every Star Wars fan. You’re right, of course, that there is no such thing as a singular Star Wars fandom, nor has there ever been (we could be speaking about fan cultures in general here). As I have written elsewhere,

“Star Wars fandom isn’t ‘broken’ nor is it’ fractured’—as an abstract concept that cannot be quantified substantively or entirely, fandom has never been in a state of unity from which it might be broken and in need of repair…what seems to be surprising to many critics and fans is that The Last Jedi might be loved and hated simultaneously, but by different kinds of fans.”

The idea of fan ‘community’ is one that has been criticised by Matt Hills, among others. As Hills writes, ‘media fandom cannot be viewed as a coherent culture or community,’ and as such, we may need to approach contemporary fandom not as a singular or coherent “culture” (if we ever really could) but rather as a network of networks, or a loose affiliation of sub-subcultures, all specializing in different modes of fan activity.’

These nuances and insights simply do not exist in fan and/ or journalistic discourses, both of which generally view fan cultures as homogeneous and Utopian, until they’re splintered and shattered by disagreement.

It is worth noting too that Star Wars has been spark and kinder for political debate since 1977, where critics and audiences had their knives out for the first film, especially regarding the representation of race (or lack thereof). Raymond St Jacques critiqued the film in the Los Angeles Times for ‘the terrible realization that black people (or any ethnic minority for that matter) shall not exist in the galactic space empires of the future.’ Jacques goes on to accuse Lucas as ‘worse than any racist’ for not acknowledging ethnic minorities, especially black people.

I would like to add that I didn’t mean to imply that bigoted voices should be dismissed as the work of trolls, but that these voices are a minor contingent of Star Wars fandom that have been over-amplified by journalists, while other more progressive actors that have been overwhelmingly pushing back against reactionary scripts are almost sidelined completely. One thing is impossible to determine, in my view, is whether these voices are legitimate Star Wars fans, trolls, or an anti-PC brigade out to aggressively attack what they view as social justice pop culture. In a chapter I’ve written recently for Henry Jenkins, Sangita Shresthova and Gabriel Peters-Lazaro’s Popular Culture and the Civic Imagination: Case Studies of Creative Social Change, titled ‘Rebel Yell: The Metapolitics of Equality and Diversity in Disney’s Star Wars,’ which will be published in February 2020 for New York University Press, I discuss the way in which the so-called alt-right have mobilized discourses of boycotting and anti-progressive rhetorics through a strategy that Matthew Lyons describes as ‘metapolitics.’ In essence, this strategy is less about attacking political institutions directly, and more concerned with upending contemporary artefacts of popular culture that is deemed, in their eyes, too progressive, and too politically-correct (if I’m being diplomatic). Many websites, like Return of Kings, are largely ideological containers for hate speech, for sexist, misogynist, homophobic, transphobic, and general reactionary screeds that might be described as Neo-Nazi. Yet the only way these minor contingents are given valuable oxygen, and as clear evidence that Star Wars fandom has been overtaken by right-wing agents, is through mainstream reproduction and recirculation, while progressive ideological currents are given little concentrated attention in comparison.

I have been misrepresented on this matter in academic discourse, even though I have been very cautious and careful not to suggest that there are no racist, sexist, or reactionary fans. I always say unequivocally that they’re easy to find if one goes looking. My concern is that journalists tend to jump on—and at times, manufacture—controversy, in the pursuit of more readers and more clicks. More concerning is the way that some academics have effectively re-produced press discourse without doing the required empirical work necessary to check the veracity and validity of journalistic accounts, be that professional, pro-am, or fan-oriented. And in this era of fake news, or what Claire Wardle has called ‘information pollution’ to avoid associations with Donald Trump, it is more crucial than ever to ensure that journalism is fact-checked, even when coming out of entertainment spheres.

To return to Disney’s Star Wars, it is noteworthy that there will apparently be a cessation of cinematic material for a while, although precisely how long isn’t yet known. Rumors abound, of course, the most interesting one being that Keanu Reeves is in talks to lead a new Jedi-focused trilogy based on The Knights of the Old Republic video-game and comic book (although not necessarily a straightforward adaptation). Until we learn more, Disney is putting all eggs in the streaming basket, with a second season of The Mandalorian coming in 2020, and two new series, one based on Cassian Andor from Rogue One, and one that has Ewan McGregor reprise his role as Obi-Wan Kenobi. Despite Bob Iger’s insistence that audiences have grown tired of Star Wars for the moment, Disney+ seems to be top of Lucasfilm’s priorities for now. We’ll no doubt see the return of Star Wars on the big screen in a couple of years or so, I reckon. There too much profit to be mined from blockbuster cinema to send it into cultural hibernation for much longer, but for the moment, the future of live-action Star Wars is on TV. Perhaps that’s for the best considering how well The Mandalorian has been received.

Will Brooker is Professor of Film and Cultural Studies and Head of the Film and Television Department at Kingston University, London. Professor Brooker’s work primarily studies popular cinema within its cultural context, situating it historically and in relation to surrounding forms such as literature, comic books, video games, television and journalism. In addition to the numerous essays and articles on film and fan culture that he has published, his books include Why Bowie Matters (2019), Forever Stardust: David Bowie across the Universe (2017), Star Wars (2009), Alice’s adventures: Lewis Carroll in popular culture (2004), Using the Force: Creativity, Community and Star Wars Fans (2002), and the edited anthologies The Blade Runner Experience (2004) and The Audience Studies Reader (2003). He is also a leading academic expert on Batman and the author/editor of several books on the topic, including Batman Unmasked (2000) Hunting the Dark Knight (2012), Many More Lives of the Batman (2015).

William Proctor is Principal Lecturer in Film and Transmedia at Bournemouth University. He is co-editor on the books, Global Convergence Cultures: Transmedia Earth (with Matthew Freeman, for Routledge 2018), and Disney’s Star Wars: Forces of Production, Promotion and Reception (with Richard McCulloch, for University of Iowa Press, 2019). William is a leading expert on reboots, and is currently writing a monograph on the topic for Palgrave titled Reboot Culture: Comics, Film, Transmedia. He has published on a wide-range of topics, including Star Wars, Batman, James Bond, Stephen King, and more.