Participatory Politics in an Age of Crisis: Henry Jenkins & Nico Carpentier (Part I)

/Henry

We launched this conversation about “Participatory Politics in an Age of Crisis”, in part, as a way of celebrating our own decade long conversations around these issues within the Civic Paths research group and the Youth and Participatory Politics Network. In particular, I wanted to direct attention to the paperback publication of our book, By Any Media Necessary: The New Youth Activism. But, clearly, the topic struck a responsive chord, allowing us to bring together participants who wanted to share their own insights about the ways debates on participatory politics are playing out in many different national contexts and across multiple disciplines. And the series has brought forward a range of literature that might speak to these issues.

In my opening remarks for what is the closing exchange in this series, I want to share some of my own current thinking about the issues the political moment in the United States raises for our understanding of the potentials of participatory politics. I am delighted to have as my conversant, Nico Carpentier, with whom I had another generative exchange some years ago.

This fall, when I was at the U.S. Library of Congress, I stumbled onto a largely forgotten book, George Huszar’s Practical Implications of Democracy (1945). Today, our popular memories see the 1940s as a golden age for civic engagement in America. The Second World War brought the United States together around a common cause -- to overcome fascism, to make the world safe for democracy -- and returning home, the “Greatest Generation” sought to build a stronger, more affluent, more forward-thinking country. These were the “good old days” in many of today’s narratives of civic decline. But, writing in the post-war period, political scientist George B. Huszar, worried that the nation might soon experience the kind of “disintegration” of democratic culture which enabled the rise of dictators in Europe and Japan. And this was because democracy had become a thing of words rather than actions. Huszar writes, “Democracy is something you do; not something you talk about. It is more than a form of government, or an attitude or opinion. It is participation.” (xiii)

Huszar made a core distinction between “talk-democracy” and “do-democracy,” arguing that democracy should be embedded into the practices of everyday life. Talk-Democracy, he suggests, is often top-down, as people consent to being governed by people who are all too ready to tell us what to do. But, “Do-Democracy” emerges from “creative participation by intelligent human beings in the ongoing process of society.” He concluded “The problem of democracy is not merely how to obtain consent, but also, how to create opportunities for participation and a determination to participate.” (13) His goal was to create “warm, personal, satisfying human relationships that develop when men join together in groups” that are empowered to take meaningful action on decisions that directly impact their lives (17).

Looking backwards, scholars of civic engagement, such as Robert Putnam (2000), point to the bowling leagues, garden clubs, Parent-Teacher Associations, and other civic organizations as helping to foster a sense of neighborliness and meaningful participation during this post-war era which they argue has been lost in more recent years. Huszar embraces similar groups, particularly those like the PTA which work together to solve shared problems: “The problem-centered-group is democratic in structure; it leads to the preservation of the integrity of the individual, nourishes his productive powers, and encourages participation. This structure is flexible, informal, stimulating and creative, with participant leadership. In contrast, the authoritarian social structure is rigid, formal, regimented, hierarchical, noncreative, and frustrating to the individual, with ‘leadership’ from the top down.” (26) Though largely forgotten today, Huszar’s concepts of “talk-democracy” and “do-democracy” have enormous relevance for our own time, where many are similarly worried about the disintegration of core democratic institutions and practices, the breakdown of civic ties within local communities, and a decline in our sense that there is any common ground to be identified amidst the sharp ideological divides between the country’s two competing political parties.

To be clear, Huszar’s “problem-centered groups” can only move forward with a great deal of talking, exchanging ideas, identifying shared values, swapping stories, forging shared vocabularies, proposing solutions, and debating the merits of different plans. But, he sees such talk as emerging among equals who understand themselves as empowered to participate, who are encouraged to contribute, and who have some expectation that their ideas will be respected by the others in their community. In a community with strong civic engagement, these problem-centered discussions may spill over into their everyday interactions -- at the barbers, at the hairdressing salon, at the grocery store, at the bowling alley, in the taxi cab, at the coffee shop and tavern (to cite classic examples of civic spaces). Through such exchanges, we accumulate social capital and learn to respect each other as vital members of a shared community. Contemporary political theorist Peter Dahlgren (2009) makes a similar point: “The looseness, open-endedness of everyday talk, its creativity, its potential for empathy and affective elements, are indispensable resources and preconditions for the vitality of democratic politics.” (90)

His idea that civic dialogues paves the way for democratic politics is only partially true. Core distinctions between civics and politics often get elided. The civic represents the shared beliefs and values, the underlying trust, which makes collective action possible, while the political encapsulates struggles over power within the decision-making process. In a well functioning civic culture, people may disagree, fight hard for what they believe in, and then accept each other back as neighbors, because there is a core democratic infrastructure which allows us to resolve conflicts and agree to disagree so that we may continue to live side by side within a particular community. Sociologist Nina Eliasoph (1998) describes the ways we increasingly avoid politics as a topic in our everyday conversations with people we care about, fearing that political disagreements have become too divisive and that the heated disagreements may fray social ties in the absence of shared civic commitments. Because we lack such mutual understandings, the community fails to come back together again, wounds do not heal, in the wake of elections and other political events. Rather than developing the basis for a shared understandings, we end up locked in a permanent culture war. Here, the political destroys the exchanges which enable the civic to persist and it is in that sense that talk-democracy may ultimately result in a loss of civic agency. Right now, around the world, democracy needs our help.

I never bought the idea that shifts in the technological infrastructure would, in and of themselves, lead in some inevitable way to a more democratic culture. For me, it has always been about how we use these communication capacities to enhance our civic and political lives. Technology offers us a set of resources and a new opportunity to renew struggles over who can speak, who can be heard, and what voices have impact on our everyday decision-making processes. Every day, I see new reasons for optimism about the potentials of participatory politics -- the ways the Parkland kids have had at shifting the ground around the gun control debate, a topic I recently wrote about with my PhD student Rogelio Lopez for The Brown Journal of World Affairs) or the ways that Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (AOC) has revitalized our political rhetoric (about which I will say more later) and everyday, I see more reasons to be worried about the state of the civic culture in my country -- as the practices or rhetoric of participatory politics are being deployed in destructive, anti-social, reactionary and even fascistic manners. I have never claimed that participation would always yield progressive results but my own optimism is more and more challenged by the prospect that we have expanded opportunities for grassroots participation without expanding or at least preserving civic norms and ethics. I had always assumed there would be a transitional period as access to the means of media production and circulation expanded and people figured out how to use those opportunities towards their own ends. I had supposed that a set of shared norms and ethical commitments would emerge as various subcommunities and subcultures experimented with alternative means of resolving conflicts and working towards shared goals. I had hoped that the expansion of voices would be included into a more diverse public sphere. So, how do we strengthen our shared understanding of the civic?

My own current research initiatives have centered around the concept of the civic imagination, looking at the ways shared cultural resources and the intersubjective sharing of our aspirations, values, hopes, and dreams, may contribute to the creation and sustaining of shared civic norms. By civic imagination, I mean the stories we tell ourselves about our past, present, and future, as we seek to address some core functions of a democratic culture. We need to use our shared imaginations in order to:

● Describe what a better world might look like and thus define our goals for social change

● Recognize ourselves as civic agents capable of helping to change the world

● Identifying how we relate to a community of others who share common needs and interests and feeling solidarity with those whose experiences and perspectives differ from our own

● Developing models of social change that can shape our plans of action

● Sustaining (in the case of the most marginalized or oppressed groups) a struggle for respect, dignitiy, freedom, equality, before we have experienced them directly.

My research team has generated two upcoming books which encourage deeper reflection around the concept of the civic imagination: Popular Culture and the Civic Imagination: Case Studies of Creative Social Change and Practicing Futures: A Civic Imagination Action Handbook. Our interest in the Civic Imagination started with By Any Media Necessary when we described the frustration expressed by many young activists who felt that the vernacular of American politics was failing their generation, not offering access to first time voters who were not already inside the political process, devolving into off-putting displays of partisanship at the expense of the shared public good, and dampening and dulling the civic imagination. We found that many of these young activists were drawn to cultural and educational mechanisms for social change and that many of them sought new vernaculars of political speech which drew upon popular culture.

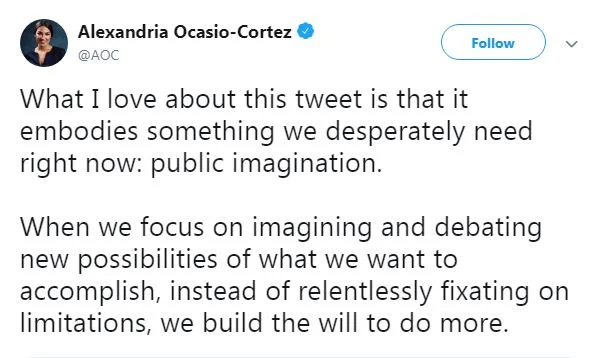

If AOC did not exist, we would probably have to invent her, since she so fully embodies the new kinds of political leadership required to speak to this new generation of citizens and activists. She has directly addressed the concept of the civic imagination in a recent tweet:

As I travel across America, I often hear youth excitement about AOC. She seems to be offering new genres and vernaculars of political speech and new models of civic participation.

Consider, for example, this video where AOC joins up with Elizabeth Warren to discuss the ending of Game of Thrones and in the process, to call attention to the ways popular media narratives might provide an opening for discussions of popular feminism and misogyny. Political leaders of previous generation often only discuss popular culture within a cultural war frame which sees cult media content as causing social problems rather than as offering a space where people can reflect on gender or racial equality. Here, AOC and Warren position themselves as fellow fans of a cult media franchise, seeing themselves as within and not outside or above popular culture, and this helps foster shared identities with their young supporters. Here, AOC is also lending her credibility to another female politician, who has sometimes been perceived as a bit cold and policy wonky.

AOC frequently draws on the vernacular of popular culture to frame her policies, for example, borrowing metaphors from game shows in order to stage a public hearing concerned with campaign finance reform.

We might understand the underlying logic of the Green New Deal, of which AOC has been a major advocate, as similar to that of speculative fiction: much as Stephen Duncombe has described earlier utopian writing as providing a provocation for critical reflection, the Green New Deal is an aspirational framework meant to start discussion around how we take more decisive action in order to address climate exchange. The particulars of the framework are less important, the details have not yet been fully hammered out, but the mere existence of a document which dares to dream differently, which asks us to imagine what another path forward might look like, pulls us away from complacency and towards efforts to address these long-standing and deepening problems in our environment.

Almost every day, AOC generates a new video which she hopes will become compelling content for her supporters to actively circulate through their social media networks. Here we see a segment of a congressional hearing where she seeks to educate the public about the differences between nonracism and antiracism and the consequences of white privilege.

Here, she creates her own dance video to thumb her nose at her conservative critics.

These acts of circulation strengthen and expand her network of support, and they encourage her followers to continuously monitor political developments and take rapid low-demand, high-impact action to address urgent problems. Often, when I write about participatory politics, I am considering grassroots, bottom-up, models, yet AOC offers us an example of what participatory leadership looks like, how political figures can use their exposure and their power to foster a more participatory model of political life. No wonder she speaks so powerfully to younger Americans of diverse backgrounds. She seems to embody so much of what we learned in researching By Any Media Necessary.

All of this leads me to a question that has been hovering around the edges of our two month long collective conversation -- Is there such a thing as “bad participation? Nico Carpentier’s model offers one answer, as I understand it: he sets a high bar for what counts as participation, which remains an ideal rather than a fully achieved reality. Participation requires an equal distribution of decision-making power amongst all participants. My own work seeks to describe opportunities for participation across different institutions, communities, practices, infrastructures, as we transition towards, struggle for, negotiate around the hopes for a more participatory culture. Participation in Nico’s sense is something we imperfectly achieve at best. Mine speaks of varying degrees of participation. Indeed, I recently suggested an approach that asks of any given instance the following:

Participation in what? How do the participants understand their own participation -- as part of a public, a market, an audience, a fandom, etc.? To what degree do they identify as part of a community or network which is larger than the individual? This focus on collective life sets a theory of participatory culture at odds with many critical accounts of neoliberalism which emphasize more individualized and privatized conceptions of public life.

Participation for whom and with whom? Who is included and who is excluded? What mechanisms of exclusion and marginalization persist despite the increased opportunities for participation?

Participation towards what ends? What are our participatory activities trying to build? What do we hope to achieve in working together?

Participation under what terms? What constraints are imposed by the technological, economic, political, and legal systems within which we operate?

Participation to what degree? -- What are the limits on the power that comes from a more participatory culture?

How we address these questions helps us to map the continuum of different degrees and kinds of participation. And it invites us to consider how these different forms of participation impact each other. Participation for some groups may come at the expense of others. Participation may even have as its goals banding together to restrict or disrupt the participation of others. Here, we might think about the kinds of troll groups that Whitney Phillips has documented or the ways that Russian hackers have sought to build on cultural divides in American culture or for that matter, the way some alt-right groups have hoped to insure the festering of these cultural divides in order to identify and recruit disaffected/angry white guys to rally behind their cause.

Building on this framework, a simple response would be to say that bad participation comes at the expense of others, that bad participation seeks to deny others dignity and the right to have a meaningful voice in the decisions that impact their lives. Bad participation seeks to shut down participation rather than to advance it. Such a definition starts from a free speech imperative -- the best way to deal with bad speech is through more speech. It does not address the desire for safe spaces, necessarily, where it may be important to expel or punish some agents in order to create a zone where others feel free to speak and maintain hope that their contributions will be appropriately valued. Are there circumstances where excluding some bad actors from participation is the best or only way to insure more equitable participation for everyone else?

Nico, what are you thinking about these days?

______________

Henry Jenkins is the Provost's Professor of Communication, Journalism, Cinematic Arts, and Education at the University of Southern California. He is the author or editor of twenty books on various aspects of media and popular culture. He is perhaps best known for Textual Poachers: Television Fans and Participatory Culture and Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. He is celebrating the paperback publication of By Any Media Necessary: The New Youth Activism, of which he is co-author. His forthcoming books include Popular Culture and the Civic Imagination: Case Studies in Creative Social Change (which he co-edited with Sangita Shresthova and Gabriel Peters-Lazaro), Participatory Culture: Interviews, and Comics and Stuff.