Participatory Politics in an Age of Crisis: Mark Deuze and Derek Johnson (Part II)

/Mark

One of the key stories behind Brexit may very well be the deplorable failure of (or frustration with) participatory politics. What happens when people can truly participate directly in the decision-making process of political institutions (and, alternatively, in the creative process of media institutions)? It opens up the process to all kinds of (more or less) sophisticated manipulation online, by actors not even necessarily involved nor physically co-present. In our lives as lived in media - which perspective is at the heart of my teaching and research (see Deuze, 2012) - we can participate anytime, anyplace, anywhere (based on the ‘Martini media’ principle, as once articulated by the BBC in its strategy for the 21st century). So can anyone else - and that makes us, as well as the process we participate in, extremely vulnerable. In other words: these processes need (long-term) care, monitoring, support, investment - something clearly absent from the Brexit process, as it tends to be lacking in many of the media industry’s attempts to harness the creativity and participation of its audiences.

A second issue affecting participatory politics is the distinction once made by Michael Schudson between informed and informational citizens. The age-old ideal of an informed citizenry that will rationally make up its mind once in the voting booth (or is rational and deliberate about all its participations in public life) has always been somewhat of a puzzling concept - as people are generally not particularly rational, and even if they are, their rationality is deeply emotional, biased, shaped by subjective experience. Schudson furthermore suggests that being informed is of little use if the citizen is not empowered to do something with that information - beyond voting once in a while. We may lament the cacophony of voices online, but at least people express themselves. And the conflict-ridden, highly antagonistic space that speech online occupies perhaps comes rather close to the ideal - voiced by Chantal Mouffe - of an agonistic public sphere, where consensus is not the ideal, but rather the truly plural exchange of difference is. To paraphrase Mouffe: the institutional process - democratic, political, industrial, or otherwise - should create the conditions for conflict to find its expression in agonistic terms, avoiding that it becomes antagonistic.

Participatory politics is premised on this notion of an informational citizenry - people that do not become citizens when called on to do so by the system, but because they are compelled to do so through meaningful acts of participation (on the local, regional, national or even international level) - in and through media. Where I see this ideal fail, in the specific context of the Brexit example, is that the ‘media logic’ of journalism and institutional politics - amplified by the ‘platform logic’ of Google, Facebook and others with their algorithms and interfaces intent on the quantity, not quality of engagement - tends to reify antagonism (between the UK and the EU, between Leavers and Remainers), and does not invest in a plurality of voices. Both the UK government and the EU furthermore fail to create truly meaningful platforms for participation and engagement for citizens to express themselves about the process. Overall, all of this just seems such a waste of an opportunity.

Derek

I think your point about how the institutions of journalism reify antagonism is particular apt, and I see that same challenge in the work I do to understand the struggles over the reproduction of entertainment content. At the end of the day, I am still most fundamentally interested in understanding industry and the institutions of (re)production. I am inspired and awed by work that my colleague Lori Kido Lopez does to make sense of activist communities, and while I hope to add to that in some small way, I think the real insights I have to offer contribute to a critical media industry studies that can make sense of how institutions respond to, manage, and even incorporate these activist voices.

In that sense, the antagonism that I see in my work between the activist participation of communities invested in a politics of popular feminism versus that of men’s rights activists or fandoms informed by the discourses of popular misogyny is not quite a struggle that industry must face on two fronts. Instead, it is grist for the mill of a franchise management logic built on multiplicity, where each opposing viewpoint in this antagonism might be served by parallel spin-off products. When Sony produced a female-led reboot of Ghostbusters, many detractors saw it as a “ruination” of a cherished past in which men sat at the privileged center of that story, engaging in all manner of participatory (but also sexist and racist) practice to make their objections heard. Sony’s assurances that it would produce other male-focused Ghostbusters product in parallel and succession to that film demonstrate not so much the power of these would-be activists to effect change so much as their value in the existing frameworks of niche marketing and product extension upon which industry decisions are made. The antagonism of participatory politics doesn’t have to produce real industry change if it is held in tension as a form of differentiated product marketing. This activism doesn’t produce change, it supports more product.

These terms of antagonism have always been useful to me. One of the first things I ever published figured fan antagonism (“fantagonism”) not just as a conflict between competing communities of interest, but also as a site of institutional management.

Mark

This is fascinating, Derek - and to me a clear sign that it is in best interest of the industry (as it generally operates) not to bring a plurality of voices into conversation with each other, nor to nurture any such encounter. Instead, profit is made out of market segmentation, pigeonholing people into to communities that can effectively be monetized. The same process works in politics. I am not advocating, nor expecting a politics or media industry policy of consensus, but simply find it regrettable that neither institution seems to be willing to embrace bringing people together with the risk that those people may truly be different and experience (each other’s) difference. I’d be interested in your work on how media professionals can really work together with and through different fan communities, and develop new creative practices, products and services in the process. Is there a ‘third way’, perhaps? One that could also inform the political process?

Derek

I share your ambivalence about appearing to endorse a model of consensus, but I still find Joseph Turow’s distinction between “society-making” and “segment-making” media to be a particularly useful way of thinking about the way that the institutions of politics and entertainment both have embraced a politics of division that sees the world as a series of distinct niches to be served through narrowcast appeals. None of that should lead us to believe that broadcasting was ever “inclusive” or that we simply need to return to some nostalgic past when we all watched and read the same things. But it does remind us that these institutions don’t have to work this way--as “natural” as these market divisions may seem, they are historically and socially constructed, and we absolutely could imagine other ways for institutions to operate in ways that encourage dialogue, interaction, and resistance to boundaries.

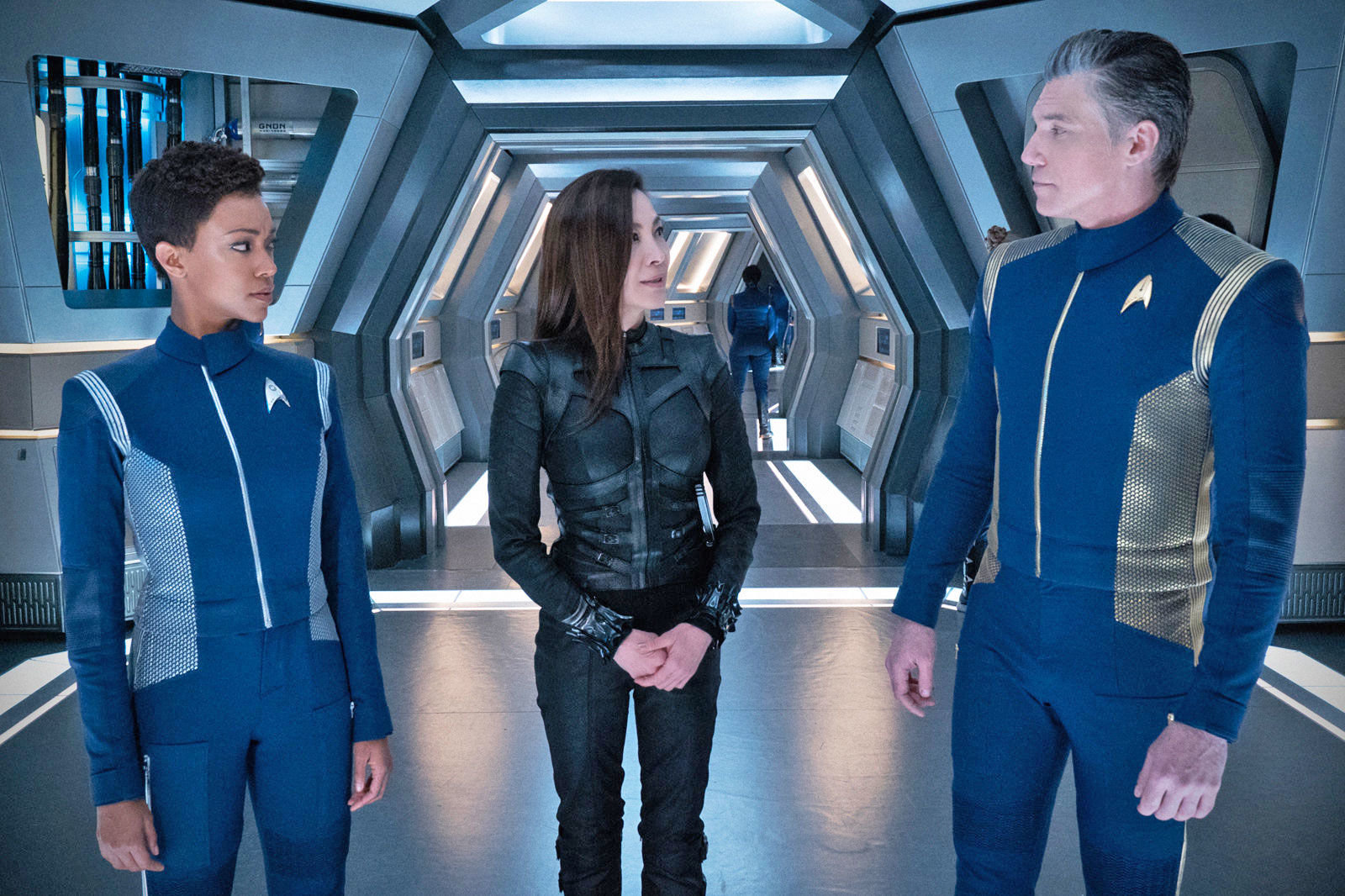

This is definitely a great opportunity to develop new practices, products, and services as you say, but unfortunately I think it is hard to find support for those new possibilities in institutions that embrace segmentation as commonsense. There is most certainly a recognition of the economic value to be gained in nurturing a greater plurality of voices in the production of entertainment content. Just recent, CBS announced plans to create a Global Franchise Group for the Star Trek franchise, which seems to exist specifically to find new ways of building the brand and connecting with audiences (particularly for a franchise that’s typically struggled to find international success). In his position at the helm of the franchise, Alex Kurtzman claimed that this initiative was aimed at “broadening ‘Star Trek’s’ brand reach by amplifying its core values globally: empowerment, inclusion, imagination, and above all, the exceptional storytelling that’s inspired generations of fans.” This is all hype of the most hyperbolic sort, of course, but I think it’s notable that corporations like CBS look to broaden their appeals and see things like empowerment and inclusion as part of that mandate. But to deliver that empowerment and inclusion, it’s more likely than not that the spin-off strategies at the heart of franchise management will be used to create separate silos so that the same brand can appeal to different people in different ways. Inclusion doesn’t necessarily mean sharing in the same things--it can operate by separate-but-equal principles.

The problem isn’t just a top down one of how industry marketing works; it’s also how some fans and other participatory consumers experience and feel those appeals and develop a sense of exclusive ownership over particular cultural experiences. There’s a zero sum game effect in play, where if someone else is now being served or newly recognized by the entertainment industries, someone who was already in the privileged position of market visibility feels like they have now lost something. It’s not just that the institutions struggle to see other ways of thinking, but also that everyday consumers have their own investments in ideas about who media entertainment is and is not “for,” using their power to participate in the policing of these boundaries.

I feel like you asked a question inviting me to be more hopeful and I dropped a lot more pessimism on our plate. I don’t mean to suggest that these institutions aren’t trying to find a third way: I want to give Disney/Lucasfilm some credit for decisions with Star Wars that seem committed (regardless of backlash) to foregrounding new voices and perspectives in the main, shared story of the franchise rather than creating spaces for “inclusivity” on the margins (in terms of characters and story, perhaps; behind-the-scenes is a whole other story). But even under the same Disney corporate umbrella, Marvel Studios’ efforts at inclusivity frequently depend on a logic of bounded separation (where individual films service different kinds of diversity). So I think there’s a lot more thinking to be done here, and I wonder, then, if you see any clearer path to a “third way” than I do? Or perhaps more broadly, what do you think is necessary to support real change in these institutional contexts?

Mark

What I particularly appreciate in these examples you share, is the insight that a true commitment to diversity (with its attendant conflicts) is not anathema to the inner workings of multinational corporations. At the same time, independent, small-scale, local or minority media and groups are not necessarily more inclusive or plural simply because their primary logic does not tend to be one of profit. The same goes for a national and local politics.

The most recent research project I have been working on with my dear friend and colleague Tamara Witschge (University of Groningen) is called ‘Beyond Journalism’: a series of case studies involving fieldwork among 20+ journalism startups in 11 countries (including Colombia, Italy, Uganda, and Canada, to name a few). A book documenting this project is published by Polity Press in November 2019. One thing we have learned from this, is not that that upstarts, newcomers, younglings, entrepreneurs, and innovators necessarily have better, more inclusive or democratic ideas of what (good) journalism is. In fact: most of these newsworkers talk about the profession in similar, quite traditional (and ideological) ways as their counterparts safely employed in the newsrooms of corporate titles like the New York Times or the BBC. However, what is quite clear is that all of them do something quite different with these values and ideas. What journalism is to them in terms of practice is incredibly diverse and multiperspectival - both in terms of content and regarding format, interface, audience relationship, and business design. This teaches me, once more, that the core values and idea(l)s of a company or political party - or indeed any institution do not necessarily lead to ‘one’ way of doing things. The challenge is to image other ways of doing journalism (and politics).

Tamara Witschge is documenting her ongoing work in this area - exploring the boundaries of journalism, embracing its true potential for diversity - among other places in the online network Journalism Elsewhere. We are also involved with the journalist initiative Multiple Journalism, mapping inspiring ways and places of journalism all over the world. Ultimately, I find that what a possible ‘third way’ of doing participatory politics and media work boils down to is: relationships, and more specifically: the ways in which we invest, nurture, explore, allow for, and embrace relationships. Between colleagues (often separated by employment status, freelance or contracted), between politicians and constituencies, between media professionals and amateurs, between makers and users, and so on. We read so much about the failure or lackluster appeal of interactivity in politics and journalism, but do not appreciate how a true ‘engagement’ (to use a term co-opted by marketers) generally only comes to fruition after significant investment (of a material, but also and perhaps primarily immaterial nature: time, energy, emotions, respect, so on and so forth).

When I was working on the Media Work (Polity Press 2007), Managing Media Work (Sage, 2011) and more recently the Making Media (Amsterdam University Press, 2019) books, I was always inspired by the ways in which the digital games industry engaged with its fans and audiences. I would tell media professionals in other industries to take their cues from game studios who significantly invested in their communities of gamers. Some studios still do a stellar job in this respect (Amsterdam-based Guerilla Games, responsible for the breakaway hit Horizon Zero Dawn, is a good example). I remember Henry Jenkins talking about the show creators of Lost as another example of this. Do you see currency in this approach?

Derek

Absolutely. I see that institutional commitment to supporting this feeling of shared engagement and community across professionals and fans in the work I have done to consider how The LEGO Group cultivates relationships with its fan--particularly adult fans who are surplus audiences in the strictest sense of the company’s core target market, but whom LEGO still hopes to engage in meaningful ways. In fact, in exchange for some access I was granted, I had agreed to share my findings with LEGO before finalizing the manuscript for Transgenerational Media Industries, and I learned that some of the analytical frameworks I used had not adequately acknowledged their felt sense of commitment to building genuine relationships with their consumers. Using a term that each of us has embraced in our work, I had written about the ways in which LEGO “manages” their adult consumers, and the company took issue with this on the basis that this term stood in opposition to the efforts being made to cultivate engagement with audiences, listening and collaboration more freely in ways the top-down language of management obscures. As much as I think these relationships can be a form of management, I understood where they were coming from and tried to acknowledge these values a little more in my revisions, because that kind of corporate value certainly seems better than ones based in control or discipline.

That said, as much as we can see and encourage these attempts to communicate and build relationships with fans and consumers more broadly, I think it matters who is being listened to and what relations are being supported through these bridges of communication. The alt-right groups that I have studied have loosely attempted to organize boycotts of film franchises and studios that they see as complicit in the rise of popular feminism, and I’m quite satisfied to see the media industries ignore them. But when some of the misogynist and racist discourses that circulate in these alt-right spaces diffuse into everyday forms of fandom, sometimes entertainment companies do listen and cite the resistance of “fans” and the potential for backlash as a reason not to pursue greater inclusivity. So I’m not sure that the willingness of media industries to listen and build relationships is enough. What also seems necessary to me is the need for relationships to be built across different fandoms and consumer groups, too. On the one hand, this could generate conversations that lead to empathy and recognition of others. On the other, fans communicating with one another across the lines of market segmentation by which media industries imagine them seems to me like it would have a lot of potential to challenge and disrupt those very industry constructions, rather than playing into them.

In talking about the potential for building relationships across the lines of social division, I wonder if we can see the questions we’re asking about both entertainment and politics intersecting in the case of Chris Evans, whose next post-Captain America project seems to be creating a political website aimed at putting multiple political viewpoints in dialogue with one another. I’ve been thinking a lot more generally about the ways Evans has used his association with that franchise to claim moral authority as a political actor/activist; but this project seems more broadly relevant to both our interests in that his stated aims are not to provide consensus, nor an echo-chamber for a single political niche, but instead a dialogue and relationship between multiple perspectives (potentially, our “third” path). Of course, it’s all very disappointingly limited, too, in that the aims of this new platform, at least so far, are described in the binary terms of getting “both” sides of an issue heard, rather than imagining a more diverse network of political participants. But this example seems to encapsulate a lot of what we’re identifying across politics and entertainment both. I don’t expect that this one website will change much, but in its aims I do see some possibilities.

Mark Deuze is Professor of Media Studies at the University of Amsterdam’s (UvA) Faculty of Humanities. From 2004 to 2013 he worked at Indiana University’s Department of Telecommunications in Bloomington, United States. Publications of his work include "Media Life" (2012, Polity Press), and most recently “Making Media” (January 2019; co-edited with Mirjam Prenger, Amsterdam University Press), and “Beyond Journalism” (November 2019; co-authored with Tamara Witschge, Polity Press). Weblog: deuze.blogspot.com. Twitter: @markdeuze. E-mail: mdeuze@uva.nl. He is also the bass player and singer of post-grunge band Skinflower.

Derek Johnson is Associate Professor of Media and Cultural Studies in the Department of Communication Arts at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He is the author of Transgenerational Media Industries: Adults, Children, and the Reproduction of Culture (Michigan, forthcoming 2019) and Media Franchising: Creative License and Collaboration in the Culture Industries (NYU, 2013). His other books include the edited volume From Networks to Netflix: A Guide to Changing Channels (Routledge, 2018) as well as the co-edited works Point of Sale: Analyzing Media Retail (Rutgers, forthcoming 2019), Making Media Work: Cultures of Management in the Entertainment Industries (NYU, 2014), and A Companion to Media Authorship (Wiley-Blackwell, 2013).