Remediating Comics for Cinema: An Interview with Drew Morton (Part Two)

/ As I read through your various examples across the book, it is clear that the concept of making a film look like a comic book means something different to different filmmakers, as comic-bookness gets conveyed through a range of different aspects of cinematic style. No one seems to try to capture every aspects of comics -- hard to know what that would even look like -- so what factors shape the choices of techniques to be foregrounded in any given adaptation?

As I read through your various examples across the book, it is clear that the concept of making a film look like a comic book means something different to different filmmakers, as comic-bookness gets conveyed through a range of different aspects of cinematic style. No one seems to try to capture every aspects of comics -- hard to know what that would even look like -- so what factors shape the choices of techniques to be foregrounded in any given adaptation?

That’s a great question and one that I could easily answer it by going the other way. What if a comic book artist wanted to make a “filmic” comic book? Would she produce a panel breakdown akin to the quick cutting and intellectual montage of Sergei Eisenstein or try to find a way to use splash pages like Jean Renoir or Jacques Tati might? I think of Chris Ware’s tribute to Yashiro Ozu’s Tokyo Story or even the fantastic graphic novelization of Alien by Archie Goodwin and Walt Simonson. The Ware piece pays tribute to Ozu’s knee-high framing, his use of reoccurring images, and the graphic simplicity of his images. In three images, we experience the profound loss of Tokyo Story - a husband loses his wife to the forward march of time and technological development in post-war Japan. Alien, on the other hand, uses an alternation between splash pages and complex multiframes with a fury of smaller panels to capture the varied temporal rhythms of Ridley Scott’s film - between the deliberate contemplation of the early scenes of the Nostromo to the more traditional “haunted house” sequences that come towards the end.

In short, I think the methods vary because the strengths, weaknesses, and preoccupations of the comics writers and artists vary. Most of the filmmakers seem to be asking themselves “What are the key characteristics of this comic?” Sometimes, the filmmakers in question are profoundly wrong in interpreting the source material. I think Frank Miller’s adaptation of The Spirit is a prime example. He has almost no interest in capturing Eisner’s style (the film looks more like Sin City than the graphically and tonally varied strips Eisner produced). While I think it’s naive to expect “faithfulness” from an adaptation in the way that term has come to be used (every narrative nook and cranny from the books must appear in the film), I think a general faithfulness to - in this case - the spirit of the work is what most filmmakers strive for and what most audience members expect (which brings us back to Nolan - it’s not as if his films were lambasted for not being “faithful”).

Often, remediation involves borrowing prestige from an older media form, such as the use of the leather bound book in the opening credits of film versions of literary adaptations. But in the case of comic book films, most of us would agree that the cinema has established a much higher cultural status than “graphic novels” have to date, and there’s often a hint of disdain in many of the quotes you provide here of the film’s producers when they discuss the story’s comic book origins or fan base. In this context, does stylistic remediation constitute a form of slumming it?

You’re exactly right - there is a cultural aspect to remediation as well. I think in the 1970s and 1980s, remediating style was viewed in relation to the 1960s Batman television show. The garish colors, the onomatopoeia, the canted angles all came from the comics. Will Brooker does a fantastic job in Batman Unmasked on tracing these aspects back to the 1960s comics, dispelling the scapegoating of the television program for introducing camp and baroque stylization to the “gritty” and “serious” world of Batman. But the legend became fact and the cultural legacy of that television show cast a long shadow over comic book movies. When you read about the production of Donner’s Superman, you can absolutely see that cultural prejudice against the comic book. The Salkinds and Richard Donner wanted to distance that project as far as possible from its “cartoon” origins, so they hired Oscar winners like Marlon Brando and Gene Hackman to star in it and trendy screenwriters like Mario Puzo and the team behind Bonnie and Clyde to write it.

But as graphic novels helped comics come to cultural prominence in the 1980s, I think that tide began to shift. It also helped that many of the directors brought on to do these projects are fans of the original texts and relish the opportunity to strike up collaborative relationships with the writers and artists while adapting the properties - folks like Guillermo del Toro, Robert Rodriguez, and Zack Snyder.

That being said, I think there’s a certain paradox now and Snyder’s evolution - if we want to call it that - is indicative of it. Films that remediate comics rely on a certain amount of familiarity with comic books and their form. If the readership isn’t there - as I mentioned in an earlier answer - what stylistic primer does the audience have to appreciate a film like Scott Pilgrim vs. the World? So these filmmakers are torn between making a film that represents their interests in the property and their affection for the artwork while balancing it with a budget overruns for such stylistic embellishments and walking that line between a niche and a wide audience. Notice that Snyder’s last two films - Man of Steel and Batman v Superman - look nothing like 300 or Watchmen. They’re pretty strongly in the “realistic,” “gritty,” and “serious” Nolan/Marvel camp. And there’s an aesthetic loss in serving the master of manageable budgets and appeasing a large audience - which is one of the main reasons I think so many contemporary comic book adaptations are visually boring. As fun as Guardians of the Galaxy and The Avengers are, I cannot remember one action sequence from those films with the vividness of the finale of 300 or the race sequences in Speed Racer. Although Ant-Man and Doctor Strange were certainly a step in the right direction!

Throughout, you distinguish transmedia style from transmedia storytelling, noting that the first constitutes “intertextual references” but not necessarily “narrative embellishment.” Can you say more about this distinction here? What do you see as the advantages of transmedia style? How might it be related to the concept of High Concept, as explored by Justin Wyatt?

Transmedia storytelling requires a certain experiential buy in from the audience. As you’ve noted, in order to fully grasp the Enter the Matrix video game, you have to have seen the first film. In order to understand some of the pivots and characters in the second film, you have to have played the game and watched The Animatrix. Stylistic remediation, on the other hand, can benefit from previous knowledge but does not require it to be comprehended or appreciated. This conflicts slightly with the answer I just gave when I said that Scott Pilgrim cannot be fully appreciated without previous knowledge of the comic book, but hear me out.

300 is a perfect example - Frank Miller’s comic was a bit of a niche title that lacked the visibility of his work with DC or Marvel. Yet, it outgrossed more than Batman Begins. In fact, aside from the first Men in Black film, it’s the only non-DC or Marvel adaptation in the top thirty grossing comic book adaptations (and remember, 300 was rated R - not PG-13). If you go back and look at reactions to 300, a lot of the energy and excitement around the film had to do with its visual style. Like The Matrix, Snyder found a aesthetically unique way to remediate Miller’s style and that provided the Warner Bros. marketing team with a striking visual hook - the sepia toned watercolored skies and the “flat” ink splatter blood effect. This is where you can see some overlap with Justin Wyatt - the idea that there’s a strong linkage between visual style and marketing in films made after the 1970s. The advantages of transmedia style are that it provides ammunition for the marketing departments to help rope in new viewers while appeasing fans of the books. It doesn’t alienate consumers the same way transmedia storytelling can, which makes folks feel like they have to do homework before coming into the room.

Yet, what makes 300 and Scott Pilgrim differ is the cost of their remediations. 300 cost $65 million, Scott Pilgrim was somewhere between $85 and $90 million (both without marketing costs accounted for). Essentially, 300 was a relatively niche comic book and the film and was budgeted accordingly (at the time, $65 million was about the average for a Hollywood film and $200-250 million is the average for a superhero film). The visual hook aided it in breaking through to a popular audience. Scott Pilgrim, on the other hand, was a niche comic book that ballooned well beyond the average for such a film. It also didn’t help that Universal showed the film for free, numerous times, throughout San Diego Comic-Con. Needless to say, the disadvantages to transmedia style are that it can be a costly investment (Universal spent $1.5 million just on comic book transitions for Ang Lee’s Hulk) that take budgets for smaller properties well beyond their ceiling faster than a speeding bullet.

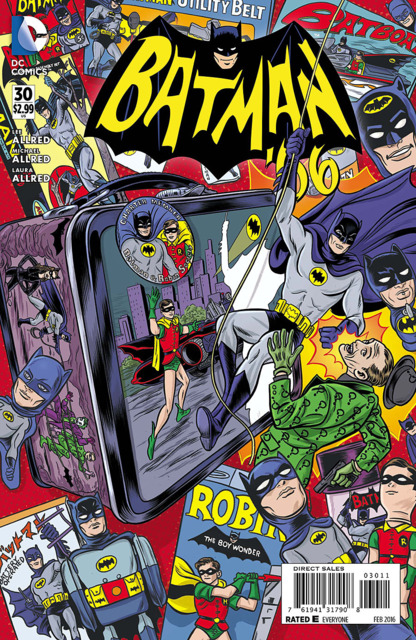

You use Batman 66 as an early example of stylistic remediation that has since been repudiated by many fans and critics as “camp,” a term which had a different cultural status in the 1960s than it does now. What do you make of the resurgence of interest in Batman ‘66 both through the comic series and the direct-to-video feature film recently released? One of many things that seems to be going on here is a re-engagement with the particular stylistic choices associated with the original, now being remediated back into comics.

Allow me to get a little autobiographical for just a moment. I was drawn to the Batman 66 series and film when I was a kid because of Tim Burton’s 1989 film. Yet, at the time, the series was relatively difficult for me to see. I think it ran on syndication on some local network. If memory serves, Will Brooker does a great job of tracing how DC distanced themselves from the property and suppressed it for decades because of its negative cultural stigmas. Now, they’ve recently changed direction. Needless to say, once the Burton films and the fantastic Animated Series took off, I spent a good period of my life planting my flag in the “Batman is grim and gritty! He’s serious - not campy!” trench.

Then we got “serious” Batman. We got him in the comics for at least 30 years. We’ve had him in the movies for the better part of 25 years. And you know what? I’m getting really bored with “serious” Batman. I awaited Batman v Superman with dread and the end result felt like I had been forced to drink the sourest of lemonades. I respect it to a certain extent for being so profoundly unpleasant, for linking Bruce Wayne to Trump (although that rings a whole lot differently now than it did last spring), and for focusing on the physical consequences of superhero action (the opening and the Scoot McNairy character), but it is not a film I look forward to re-visiting anytime soon. I never thought that after getting a Batman tattoo that I would be apathetic about an upcoming Batman film, but the DCU has gotten me there.

But you know what? I rewatched Batman 66 when the Blu-Ray release came out and bought the first couple issues of the comic. It’s not a flavor of Batman I want all the time, but it is a lot of fun because of its self-consciousness. The art of the comic, as you note, owns the dutch angles, onomatopoeia, cheesy puns, garish colors, and even the ben-day dot printing process that inspired the Pop Art movement that was evoked by the show. The variant cover galleries at the back of the trades are some of my favorite pieces of contemporary Batman art. They’re refreshing and I appreciate the multiplicity of Batman interpretations now. I think that’s why there has been a bit of a resurgence - something that was formerly forbidden or disavowed has made its way back into the cultural ecosystem at a time when every flavor of Batman has the same level of peatyness. Now if only we can get Warner Bros. to do a proper Blu-Ray release of Mask of the Phantasm and The Animated Series!