A New History of Laughter in China: An Interview with Christopher Rea (Part Two)

/Part of what brought us together was your recognition of some parallels between what I had written in What Made Pistachio Nuts? about the “new humor” in the American context in the early 20th century and the kinds of developments your book documents. So, could you say a bit more about the similarities and differences in terms of what was happening around jokes in American and China during this period? Ah, the “new humor”—same marketing strategy! In both cases, there’s this sense that the modern era calls for a new comedic sensibility. I see a lot of parallels, including in timing. Some jokes stand the test of time and are endlessly circulated. But, even as they make new conquests, jokes seem to have a built-in obsolescence factor. So we promise that this “new” one isn’t stale—actually, it just has to be new to you.

One major similarity is an increase in the volume of published jokes by several orders of magnitude. You have a rising tide of publications that lifts all literary boats, including humor’s humble sloops and dinghies. Writing jokes and amusing “filler” material for various periodicals became a means of livelihood. One writer, Zheng Yimei, was known to his colleagues as the Fill-in-the-Blank King, bubai dawang.

Another is that the rise of the periodical press overlapped with the popularity of a vaudeville culture of variety amusements. The Chinese word for magazine—zazhi, or “assorted records”—resonates with the new focus on miscellany in literary culture, and the choose-your-own-adventure ethos of the new amusement halls springing up in Shanghai, Hong Kong, and Singapore in the 1910s and 1920s. Funhouse mirror, floor one. Magicians, floor two. Comedians, floor three.

Finally, joke books, live performances, comic strips, slapstick films, and other forms of amusement became cheaper in the early twentieth century thanks in part to technological advances and urbanization, which created economies of scale. As it became cheaper, humor became more democratic.

As for differences, the main one was language. A new vernacular style of writing was just taking hold in the 1910s and 1920s, so you have humor collections appearing both in a written vernacular close to everyday speech, and in classical-style literary Chinese. The actual content of the jokes was not terribly different, though my impression—having not done a rigorous quantitative comparison—is that you find more puns in Chinese, a language of homophones.

Much of the debate about jokes in America had to do with their ties to a new commercial culture where the desire to make people laugh was divorced from the desire for moral instruction or critical commentary (or so the discourse of the period argued). Are these same criticisms directed against Chinese humorists and jokesters of this period? Why or why not?

In What Made Pistachio Nuts? you describe religious figures and members of the middle class decrying a new cultural force that would see any situation “thrown into the cauldron and cooked into some fashion of mirth.” Chinese critics voiced similar objections. One in the 1930s reminded advocates of “the so-called humor” that “laughter is like tobacco and alcohol: a little is a stimulant, but too much is narcotic.” China had just woken up from its dynastic lethargy—and now humor was putting it back to sleep.

Moral instruction (wen yi zai dao) and personal expression (shi yan zhi) are the two main writerly impulses—so says traditional Chinese literary theory. Either you set the world straight or you vent your own feelings. The moralists of the modern age weren’t just old fogies satirizing modern women in short skirts; you also have progressivists mocking their peers for wallowing in nostalgia for the glory days of the Ming dynasty instead of making revolution in the streets. So, yes, you see the same antagonism toward a new entertainment culture of pictorial magazines, comic strips, amusement halls, and movies. I would add that the “serious-minded” critics also often envied the entertainers’ commercial success.

There are many references here to “western jokes” being popular in China during this period and you also describe various ways Chinese jokes and other humor got exchanged across a diasporic community in the early 20th century. How might we understand humor and laughter as part of a larger set of cross-cultural exchanges during this period? It’s often said that humor is one of the hardest forms of cultural production to translate across national and linguistic barriers. So, what survived and what got lost through these exchanges?

“Laugh, and the world does not usually laugh with you, because the world generally fails to see just what there is to laugh about.” T.K. Chuan, an American-educated writer, also claimed that “it is not laughter that brings men together.” But he did so in an English-language Shanghai weekly, The China Critic, which played handmaiden to a humor craze in the 1930s, translating jokes back and forth with a Chinese-language humor magazine called The Analects Fortnightly. His colleague Lin Yutang, one of modern China’s most influential humorists, was more optimistic. On the eve of WWII, he facetiously suggested that if each nation were to send a representative humorist to a Peace Conference, all war plans would collapse because each would claim that it was all his own country’s fault.

Chinese humor was as internationalized as the Chinese press itself. Chinese humorists drew from any sources they could get their hands on. They read Tokyo Puck, Russian satirical plays, American comic strips like Mutt & Jeff (figure below) and Bringing Up Father, London’s Punch magazine. They translated Mark Twain and modeled magazines on The New Yorker. One Beijing-based periodical reprinted Chinese cartoons with translated French captions. Playwrights wrote comedies of manners channeling Wilde and Shaw. Filmmakers adapted Lady Windemere’s Fan and replicated gags from Buster Keaton.

A Chinese version of Mutt & Jeff in Shanghai’s Eastern Times Illustrated (ca. 1910s). Having cooled down on a hot day by strapping a block of ice to his head, A. Mutt is beaten by a sweaty companion when he dons gloves.

As for “western jokes,” that was often a lazy marketing device like “new jokes.” In the 1920s, one writer claimed that Chinese jokesters were cribbing from old dynastic joke collections, changing the names to foreign names, and passing them off as “western jokes.” But you do have lots of translation and bilingual humor, literary and pictorial (figure below).

Vermin make their home in the newly-established Republic, spoiling the fruit of earlier labors. From Shanghai’s The True Record (Mar. 1913)

My impression is that pictorial humor traveled wider and translated more easily than wordplay, but even still, China—then as now—had some remarkably talented translators who were able to bridge the language gap.

You have very interesting things to say in the book about the reception of slapstick comedies by Harold Lloyd and Charlie Chaplin in China and the ways they intersected with local slapstick traditions. Most of us know little to nothing about silent film comedy in China. Can you give us some glimpses into what was happening in Chinese cinema during this period and how it connected with the other kinds of humor you discuss?

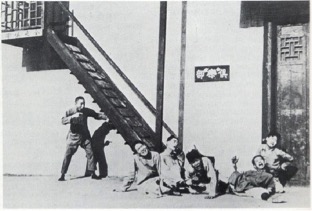

The earliest extant Chinese film we have today is a slapstick comedy called Laborer’s Love (aka, Romance of a Fruit Peddler, 1922) (figure below). That’s pretty late in terms of film history, global or Chinese. But it’s no accident that it’s a comedy, which were then popular worldwide, or that it’s so fascinated with trick photography and gadgets. As Xinyu Dong has shown, the film was responding to American films made just a year earlier, like Buster Keaton’s The Haunted House (1921), which also features a staircase that turns into a slide.

I show that trick camerawork in films like Laborer’s Love—such as a frame showing two images of a character dreaming of himself—can also be found in contemporaneous portrait photography. You could go to a studio and sit for a photograph in which you appear to be pouring yourself tea, driving yourself in a car, or begging yourself for money, thanks to the miracle of double exposure (figures below).

Trick photographs using double exposure, ca. 1910s-1920s. The top one (with watermark) is printed on a postcard. The bottom one features a teenaged Puyi, the recently-deposed last emperor of the Qing dynasty.

These novelty photographs had been around since the 19th century, but their reception in China was unique. For example, in the Confucian Analects the Master twice advises that it is better to ask of oneself (qiu ji) than to ask of others—so they called the money-begging photo a “self-beseeching photo” (qiu ji tu). It’s a consumer product that’s at once allegorical, playful, and ironic.

Lloyd and Chaplin were extremely popular in China. Their films screened regularly, and they were both written about extensively in movie magazines (figure below). The handsome, friendly Lonesome Luke character was especially popular; Dong points out that the Laborer in Laborer’s Love even puts on Luke-style glasses at one point. Lloyd’s popularity plummeted in 1929 due to the Chinatown stereotypes in his first talkie, Welcome Danger (1929). Wisely, he apologized, and the brouhaha died down.

Harold Lloyd on the cover of the first issue of Shanghai’s The Motion Picture Review (Jan. 1920)

Chaplin was revered as an “artist” and inspired local imitators as early as 1922 (figure below). His short visit to Shanghai in 1936 was a sensation. And by then, the Chinese film industry had been stable for about a decade, and you had actors specializing in comic roles, like the skinny Han Langen, who often paired with Liu Jiqun or Yin Xiucen as a Chinese Laurel and Hardy. Unfortunately, the 1937 Japanese invasion of Shanghai, where China’s film industry was centered, disrupted production for almost a decade.

The King of Comedy Visits Shanghai (1922), a Chinese production starring a British expatriate

Christopher Rea is an associate professor of Asian studies and director of the Centre for Chinese Research at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver. He is author of The Age of Irreverence: A New History of Laughter in China (California, 2015); editor of China’s Literary Cosmopolitans: Qian Zhongshu, Yang Jiang, and the World of Letters (Brill, 2015) and Humans, Beasts, and Ghosts: Stories and Essays by Qian Zhongshu (Columbia, 2011); and coeditor, with Nicolai Volland, of The Business of Culture: Cultural Entrepreneurs in China and Southeast Asia. He is currently translating, with Bruce Rusk, a Ming dynasty story collection called The Book of Swindles.