How I Spent My Summer Vacation (Part Three): England and Ireland

/England has always felt like a mother country to me -- not simply because (depending on who you ask) Jenkins is either an Irish or Welsh name, but also because Birmingham is the intellectual birthplace of the Cultural Studies tradition from which my work on participatory culture can claim its intellectual roots. So, while most of the other legs of the trip took me to places I had never been before, the British leg was a chance to reacquaint myself with old friends and especially to meet the next generation of British scholars who are working on fan studies or transmedia topics.

London

Our visit to London fell just about a month before the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee and a few months before the city would host the Summer Olympics. As this photograph of a British street scene suggests, she was already spruced up and flying her colors.

On May 15th, I delivered a talk about our forthcoming Spreadable Media book in the Regent’s Street Cinema, which has been hailed as the Birthplace of the British Cinema, since it was the location of the first public exhibition of motion pictures in London.

The talk was hosted by David Gauntlett, whose work on grassroots creativity I showcased on this blog not long ago. Gauntlett's critiques of media effects arguments had helped to inform my writings around the Columbine Shootings more than a decade earlier. We had corresponded off and on through the years but this was the first time we met in person. While the official video from the event has not yet been posted, someone in the audience captured and has posted the second part of the talk, including the question and answer session with the audience, and it will give you a good taste of how well Jenkins and Gauntlett played opposite each other. Here's a blogger's take on the event.

Immediately after the talk, I went backstage where I was interviewed by an Irish radio reporter, and you can again got some taste of the presentation from the version he shared through his podcast.

Nottingham

Cynthia and I then traveled by train to Robin Hood country -- Nottingham, for a conference, Contemporary Screen Narratives: Storytelling’s Digital and Industrial Contexts, which was organized by Anthony Smith. Jason Mittell and I were the two keynote speakers for the event. Jason gave a really provocative presentation, drawing on his current book project dealing with complex television narratives. In this case, he used Breaking Bad to elaborate a theory of television characters. Jason has been posting chapters from the book via Media Commons for feedback, and so you will find the text of his remarks here, and given the interest in my readership in all things transmedia, here’s a link to his chapter on transmedia entertainment, which discusses Lost and again, Breaking Bad. My own remarks centered around “Engagement, Participation, Play: The Value and Meaning of Transmedia Audiences,” and was a dry run of sorts for the presentation I gave at the Pompidou Center in Paris a week or so later. (Watch for video of the Paris version).

For me, the highlight of this event was getting to sample the rich strands of work on fandom, cult media, games, and transmedia entertainment being done by the emerging generation of British and European academics, many of whom were students of my many old friends here:

- Bethann Jones (Cardiff University), a contributor to our issue of Transformative Works and Culture, shared her perspectives on the fanmix as an emergingcreative practice: the fanmix is a compilation of songs (something like a mix tape) which is intended to explore the psychological journey of a particular character (or character relationship), sometimes inspired by a work of fan fiction, sometimes informed by the fan’s reading of an episode or the series as a whole.

- Matthew Freeman (University of Nottingham) provided an important historical corrective to a day heavily focused on contemporary transmedia experiments, exploring the kinds of commercial intertexts and paratexts constructed around Superman in the late 1930s and 1940s. For comic buffs, some of the examples used was familiar ground, but what made the talk exceptional was the ways he examined the specific industrial contexts of each of the production companies involved in developing Superman for comics, radio, live-action serials, and animation, and the contractual relations the publishers deployed to insure some degree of integrity and consistency across them.

- Aaron Calbreath-Frasieur (University of Nottingham) traced the history of meta-media and transmedia explorations by the Jim Henson Corporation and the Muppets franchise, suggesting the ways that our awareness of the characters and their personalities inform our response to their performances across multiple media platforms.

- Feride Cicekoglu, Digdem Sezen, and Tonguc Ibrahim Sezen (Istanbul University/Istanbul Bigli University) reflected on the ways transmedia could be deployed to generate civic awareness and political participation, including both examples from the highly topical Valley of the Wolves series for Turkish television and recent efforts to use alternate reality games for social change, such as the British Red Cross’s Traces of Hope and Play the New .

Sunderland

Our next stop was Sunderland, an industrial city in North East England. Sutherland is the home of British comic book artist and author, Bryan Talbott, whose graphic novel, Alice in Sunderland, will be the focus of a chapter in my planned Comics...and Stuff book project.

Reading Bryan Talbot’s Alice in Sunderland is an overwhelming experience -- not simply because of its epic scale whether judged by its 300 plus page length or by its historical scope, which traces the history of a town in Northwest England from the Age of Reptiles and the era of St. Bede through to the present moment. Talbot shows how Sunderland has functioned as a crossroads for many of the cultural currents that have shaped British history. But, even on the level of the single page, Sunderland is overwhelming because of the way that Talbot has built it up primarily through techniques borrowed from photocomics and especially through the use of collage.

Each page may feature dozens of images Talbot has collected from archives -- old photographs, documents, woodcuts, carved marble, stained-glass windows, film stills, cartoons, and printed books, all jockeying for our attention, each conveying separate bits of information relevant to the historical narrative he is developing, but each gaining far greater meaning when situated within the book’s gestalt. At the center of this narrative, as its title might suggest, is the story of Lewis Carroll, the author of Alice in Wonderland, who lived for a time in Sunderland and met Alice Liddell, his young muse, for whom his fairy story was dedicated. On the surface, the book can be read as an obsessive argument for the priority of Sunderland over Cambridge as the site from which to understand the origins of Carroll’s Wonderland. In the process of making such claims, Talbot goes further, linking Alice and Carroll to a much broader array of stories (from ancient mythology to music hall comedy) which have sprung from the same geographic and cultural roots.

Sunderland, thus, is a project in radical intertextuality, forging links between dispersed narratives drawn from both history and fiction, mapping them onto a highly localized geography. For all of its historical expansiveness, the core structure of the book is a tour, walking up and down the streets of Sunderland, pointing out various monuments and landmarks, and linking them into the emerging narrative of British history. And on yet another meta-level, Talbot is trying to link his own medium, comics, to a much broader history of artistic practices which combined words and pictures to construct narratives, including a consideration of Carroll’s relations with his illustrator John Tenniel, the Bayeux Tapestry, William Blake, and William Hogarth, as well as patches of many different comics genres.

Given the book’s focus on the local history and geography of Sunderland, I was eager to visit some of the depicted sites myself, and to try to get a better understanding of the context within which Talbot works. I was lucky to have established contact via email with Billy Proctor, a scholar of comics and popular narrative who is based in Sunderland, and through him, I made contact with Bryan and his wife, Mary, who invited us to pay them a visit. There, we shared thoughts about our shared fascination with vaudeville and music hall, and I got the chance to see some of the work in progress towards the next book in his Grandville series (which combines steampunk with the funny animal tradition).

While I was there, I found myself being interviewed for a documentary being produced about Talbot and his work (as well as by a local newspaper reporter eager to find out what would bring an “American visitor” to their city). The documentary producer Russell Wall has since shared with me this short film promoting Dotter of Her Father’s Eye. Dotter was Bryan’s first creative collaboration with his wife, Mary Talbot, a noted feminist scholar, who uses the graphic novel form to explore two father-daughter stories: the first is an autobiographical account of her troubled relationship with her father, a noted Joyce scholar, and the second is the account of Joyce’s relationship with his daughter, Lucia.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cXUKksNjR78&feature=youtu.be

And this video documents Talbot’s involvements to get young people more invested in the expressive potentials of comics as a medium.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X5t1Chy1sz4&feature=youtu.be

After our visit with the Talbots, Proctor and his colleague, John-Paul Green, took me on a brief, brisk walking tour of Sunderland on what had turned out to be a rainy, misty afternoon.

Here, you see a picture of Proctor and myself standing next to a Walrus sculpture which figures prominently in Alice: a stuffed walrus was brought back to England by Captain Joseph Wiggins (an associate of Carroll’s Uncle) and may have been the inspiration for the Walrus and the Carpenter.

Here are a few other stops along our walk, each of which plays a central role in the graphic novel:

The giant chess pieces in a children’s playground in Mowbray Park, which celebrates Carroll’s ties to the city

The Empire Music Hall, where such legendary British performers as Vesta Tilley, Guy Formby, and Sidney James once played.

The Statue of Jack Crawford, a British sailor, known as the “Hero of Camperdown,” who “nailed his colors to the mast” of the H.M.S. Venerable when it shattered during a battle with the Dutch.

Proctor, and his colleague Justin Battin, rode with us by train back to London, and we spent most of the trip totally geeking out about contemporary comics, science fiction, and fantasy franchises.

London (Round 2)

We were all going to attend the Symposium on Popular Media Cultures: Writing in the Margins and Reading Between the Lines, which was being hosted by the Center for Cultural and Creative Research at the University of Portsmouth and by Forbidden Planet, London’s best known comic book shop. The event was held in the Odeon Cinema near Covent Gardens.

Organized by Lincoln Geraghty, the conference brought together a who’s who of the top British academics working on cult media and fan cultures, including:

- Joanne Garde-Hanson and Kristyn Gorton speaking about the online reactions to Madonna as an aging female pop star

- Cornel Sandvoss examining the ways that reality television series, such as The Only Way is Essex and Made in Chelsea, played into the local imagination,

- Mark Jancovich tracing the initial critical response to the Val Lewton horror films,

- Stacey Abbott analyzing the title sequences for such series as American Horror Story and True Blood,

- Will Brooker exploring the construction of authorship around the Dark Knight trilogy,

- Matt Hills sharing insights about spoilers and “ontological security” within Doctor Who fandom,

- Roberta Pearson mapping a new project she is developing about the popular resurgence of interest in Sherlock Holmes.

My talk, “Beyond Poaching: From Resistant Audiences to Fan Activism,” sought to locate my current work on fan activism as a form of participatory politics in relation to much older debates about whether fan culture can serve as a springboard for “real political change”. Amusingly, during my talk, Will Brooker asked me a question proposed via Tweet from Alexis Lothian, one of my graduate students back at USC, a symptom of the number of friends and associates who were following some of these adventures online.

Here’s a picture of some of the participants, hanging out in a local pub, following the event.

Dublin

The following morning, Cynthia and I flew to Dublin, where I had been asked to speak at the Institute of International and European Affairs, a notable think tank which brings together business leaders, journalists, and policy leaders to discuss some of the challenges confronting the modern world. Here, I offered some critical perspectives on the ways “content” is being reshaped in the contemporary media environment. As I noted, the word, “content,” has classically been defined as “that which is contained,” as in the contents of a bottle or the table of contents of a book. But, a key characteristic of our current moment is that content (as defined by the “content industries”) is not contained, but rather content flows very fluidly across media platforms, across national borders, often shaped by unauthorized acts of circulation which intensify its meanings and may or may not increase its value.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aAffkJpYnPI&feature=player_embedded

Don’t miss the question and answer session which followed my talk, including some forceful challenges from business leaders and lawyers who felt threatened by the manipulations and appropriations of intellectual property I had depicted and by those eager to understand what Irish media makers might have to gain by embracing spreadable media.

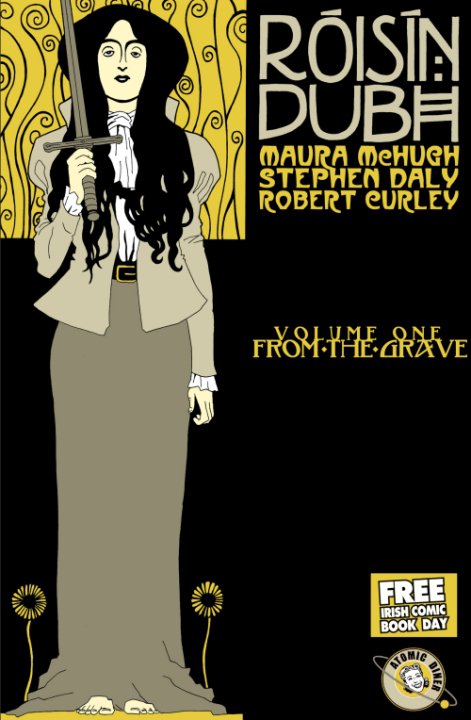

Earlier that day, I had wandered over to a comic book shop, near my hotel, which had a display of Irish comics in the window. When I brought an armful of titles to the cash register, I discovered that the owner of the shop, Robert Curley, wrote and published most of the books I was buying through his Atomic Diner imprint. I thoroughly enjoyed my purchases, which included Jennifer Wilde, a supernatural mystery set in Paris in the 1920s and involving the ghost of Oscar Wilde; Rossin Dubh, which is set in the world of Irish theater in the 1890s and involves the return of an ancient demonic force, Black Scorpion, a superhero saga set during the first world war; and the League of Volunteers, which created a team of superheros to reflect Ireland’s national identity. The writing is lively, the characters are well developed, the attempts to tap into local history, politics, and mythology are distinctive, and the artwork is compelling. Check out their website. http://www.atomicdiner.com/

Everywhere we looked in Dublin, we saw political posters, speaking to the ongoing debates around the European economic crisis and the austerity moves the government was seeking to impose. Needless to say, almost every conversation we had in Europe turned sooner or later to the current political moment. The fact that we were traveling to Greece near the end of our tour often raised graveyard humor, speculating about what currency the Greeks would be using by the time we reached there and whether it would still be part of the European Union. It became clear that much of Europe was unified behind at least one core idea – their anger towards German banks and institutions which they saw as seeking to impose their will on the other countries. This image offers a sample of the political signage debating these issues.

And this one reduces the debate to its most basic terms.

Cynthia and I spent many hours wandering around the streets of Dublin, and found ourselves utterly charmed by the city, its architecture, and its local culture.

Along the way, we visited the Trinity College Library to see the Book of Cells, a beautifully illuminated version of the Gospels produced by Celtic monks around 800 A.D., and regarded as one of the real treasures of the country’s cultural heritage.

Along the way, we visited the Trinity College Library to see the Book of Cells, a beautifully illuminated version of the Gospels produced by Celtic monks around 800 A.D., and regarded as one of the real treasures of the country’s cultural heritage.

Coming Soon: Paris!