Instead, Bethany’s feminine transhumanist experience is one of embodied joy, of emotion, and – notably – of calm oneness with the tides, a domain maintaining cultural associations to femininity, organicism, and nature. Nor is her experience strictly anthropocentric; she pursues avenues of relationality with other-than-human entities, exerting neither mastery nor violence over what she finds, but rather dwelling within them and responding with what we might see as a feminist ethics of care.

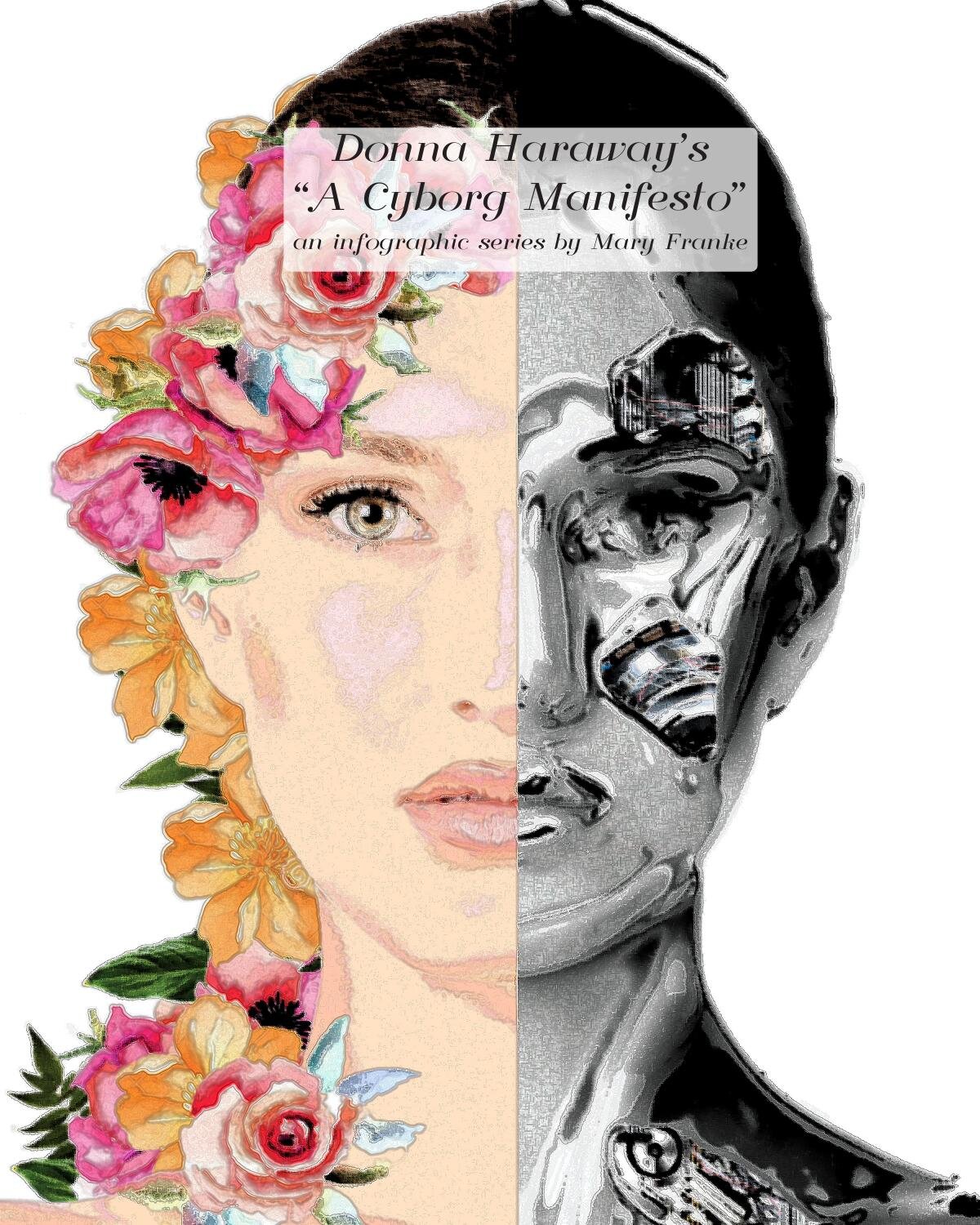

The “data” to which Bethany aspires cannot, therefore, be reduced to a brute overcoming of fleshly femininity in order to achieve Robocop-esque characteristics of masculine rationality, progress, and technoculture – the Extropian-inflected “techno-masculinist” transhumanism lambasted by Donna Haraway. Instead, it is posited as something organic and affective, sensual and deep, allowing her to inhabit several non-isomorphic and intersectional categories simultaneously yet without losing either her identity or her embodied materiality in the process.

This framing of a feminine-allied transhumanist transformation is reiterated in the closing scene of the final episode, in which the character of Edith Lyons is becoming one of the first subjects to upload their brain to the cloud. In the year 2034, she is living out the dream that Bethany was so admonished for coveting as a teenager. Edith muses upon the process slowly, ecstatically, as she lays in an airy laboratory:

“I’m not a piece of code. I’m not information. All these memories, they’re not just facts, they’re so much more than that. They’re my family. And my lover. They’re my mum, and my brother who died years ago. They’re love. That’s what I’m becoming now. Love. I am…love” (Years and Years E6).

Even as she participates in the extreme, fringe limits of transhumanism – that of relinquishing the body altogether and downloading the brain as code – Edith, too, rejects the overly masculinist undergirding of transhuman transformation as one grounded in logic, in violence, in sovereignty, in mastery, and in individualism.

As another figure of what we might term feminist transhumanism, she too emphasises relationality and symbiosis in her transformation, expressing a sprawling sense of interconnectedness, affect, care, and a profoundly feminine positionality that rejects reduction of memories into hard code and an attendant disavowal of the (feminine, subjective, natural) flesh.

Just as Russell T Davies prompts viewers to imagine slow changes in the ways we will culturally perceive biohacking and technological modifications in the future, so too do such scenes as this lead us to imagine a gradually developing future of transhumanist philosophy that is uncoupled from the cult of Elon Musk and Extropianism, transforming from “techno-masculinism of a self-caricaturing kind” to a relational philosophy embedded in a feminist ethics of care, radical political potential, and an intersectional formation of gendered subjectivity.

And yet even Bethany’s “fully integrated” feminist transhuman futurity, transplanted straight from science fiction as the image seems to be, may not be far off as one might expect. Today, when biohacking attempts are successful, they are often described in a language of expanded embodiment, of (extra)sensory pleasures, and of blissful interconnectedness that strongly recall Bethany’s own description of being transported “inside” a wave, a tide, or an electronic connection.

In a 2019 study, scholar London Brickley describes his encounter with Matt Henna, a lifelong science fiction fan and biohacker who had embedded neodymium (N52) magnets under the flesh of his fingers five years before. Brickley writes,

As the fingers healed and the nerves grew back around the magnetic strips embedded within, his sensitivity to the metal’s vibrating pull was becoming ever more acute. This new sense allowed him to communicate with the world around him in a whole new way, and he was learning to interpret its whispers. He can now sense when he is around power structures by how his nerves begin to hum. He can run his hand over his electronics and feel the boundaries of their presence, is even able to diagnose his laptop’s dying battery whenever the pulse of its heart starts to slow and skip a beat. He can sense the kind of electricity that is in the air. (10)

For Matt, as for Bethany, to be a biohacker – a transhuman, a cyborg, a human-machine hybrid – is not so much to uncouple mind from body, as to radically reimagine the entanglement between the two. Corporeal sensation and affect still reign supreme; for Matt as for Bethany, one can hardly say that the body is disposed of altogether. Instead, it becomes embroiled in a whole cacophony of more-than-human forces, structures, and networks to which our sensory capacities in their present form do not permit us access.

The body is not disavowed; it becomes something new. Brickley sharply articulates the nature of the shift, as he notes that the integration of mechanical parts into the organic body:

transforms the hacker into someone/something that no longer simply communicates with other human users through technology but communicates with other technology through the body. The classical digital paradigm of bodies communicating a message through a digital medium or screen…becomes inverted, as the communication now takes place between the pieces of electronic tech using the organic flesh as the medium of transport. (22)

The experience of Matt and other biohackers might therefore be approximated to a proto-iteration of the sort of feminist transhumanist transformation embodied by Bethany Lyons – a state in which transhumanist subjects will not yet have attained the status of pure data like Edith Lyons, but will still inhabit an embodiment far different to ours as we currently understand it. One will be able to live digitally through technological embodiment; to experience the rich textures and diffuse pleasures of a transversally interconnected more-than-human world, all the while without doing away with the sensations, consciousness, and phenomenology of the organic flesh, nor discarding its intersectional torques and gendered subjectivities.

Extrapolating from the underground practices of present-day transhumanist subcultures, to the queer techno-dystopian/techno-utopian future imagined by Russell T Davies, an examination of Bethany’s storyline in Years and Years thus permits one to reflect creatively and critically upon the future of biohacking, cyborg identities, and a speculative transhumanism that might be queer, feminist, and intersectional in scope rather than violently masculine; a feminist transhumanist turn that, indeed, might be upon us sooner than we expect.

Works Cited

Adams, Tim. “When man meets metal: rise of the transhumans.”Guardian, 29 Oct 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2017/oct/29/transhuman-bodyhacking-transspecies-cyborg. Accessed 21 Feb 2021.

Banbury, Tamara. “Where’s My Jet Pack? Online Communication Practices and Media Frames of the Emergent Voluntary Cyborg Subculture.” Unpublished MA Thesis, Carleton University, 2019. https://curve.carleton.ca/system/files/etd/387fa17a-003c-4dd9-a1bd-7fc3b8e27cc3/etd_pdf/12c315671b2bc4dbcbaec32c0c7f4aa0/banbury-wheresmyjetpackonlinecommunicationpractices.pdf. Accessed 26 Feb 2021.

Brickley, London. “Bodies Without Borders: The Sinews and Circuitry of ‘folklore’+.” Western Folklore, vol. 78, no. 1, 2019, pp. 5-19.

Cox, Lara. “Decolonial Queer Feminism in Donna Haraway’s ‘A Cyborg Manifesto’ (1985).” Paragraph, vol. 41, no. 3, 2018, pp. 317-332.

Davies, Russell T, creator. Years and Years. BBC and HBO, 2019.

Davies, Russell T. Screenplay of Years and Years, Episode 1. http://downloads.bbc.co.uk/writersroom/scripts/Years-and-Years-Ep1.pdf. Accessed 24 February 2021.

Delaney, Brigid. “Years and Years is riveting dystopian TV – and the worst show to watch right now.” The Guardian, 7 Apr 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2020/apr/07/years-and-years-is-riveting-dystopian-tv-and-the-worst-show-to-watch-right-now. Accessed 26 Feb 2021.

Ferrando, Francesca. “Is the post-human a post-woman? Cyborgs, robots, artificial intelligence and the futures of gender: a case study.” European Journal of Futures Research, vol. 2, no. 43, 2014, pp. 1-17.

Fuller, Steve, and Veronika Lipinska. “Transhumanism.” Social Epistemology Review and Reply Collective, vol. 3, no. 11, 2014, pp. 25-29.

Gane, Nicholas, and Donna Haraway. “When We Have Never Been Human, What Is To Be Done? Interview with Donna Haraway.” Theory, Culture & Society, vol. 23, no. 7-8, 2006, pp. 135-158.

Haraway, Donna. “A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century.” In Manifestly Harawayby Donna Haraway and Cary Wolfe, University of Minnesota Press, 2016, pp. 5-90.

Hayles, Katherine N. “Unfinished Work: From Cyborg to Cognisphere.” Theory, Culture & Society, vol. 23, no. 7-8, 2006, pp. 159-166.

Kafer, Alison. Feminist, Queer, Crip. Indiana University Press, 2013.

Oremus, Will. “Choose Your Own Sixth Sense: DIY superpowers for the cyborg on a budget.” Slate, 14 Mar 2013, https://slate.com/technology/2013/03/cyborgs-grinders-and-body-hackers-diy-tools-for-adding-sensory-perceptions.html. Accessed 22 Feb 2021.

Regis, Ed. “Meet the Extropians.” Wired, 1 Oct 1994, https://www.wired.com/1994/10/extropians/. Accessed 22 Feb 2021.

Renstrom, Joelle. “What Would It Mean for Humans to Become Data?” Slate, 30 Jul 2019, https://slate.com/technology/2019/07/years-and-years-finale-bethany-transhumanist.html#:~:text=Years%20and%20Years'%20transhumanist%20character%20demonstrates%20the%20conundrum,by%20merging%20human%20and%20machine.&text=In%20the%20premiere%20of%20the,scheduled%20a%20talk%20with%20them. Accessed 22 Feb 2021.

Rogers, Adam. “HBO’s Years and Years Unlocks Sci-Fi’s Ultimate Potential.” Wired, 11 Jul 2019, https://www.wired.com/story/review-years-and-years-hbo/. Accessed 26 Feb 2021.

Rothblatt, Martine. “Mind is Deeper Than Matter: Transgenderism, Transhumanism, and the Freedom of Form.” The Transhumanist Reader: Classical and Contemporary Essays on the Science, Technology, and Philosophy of the Human Future. Edited by Max More and Natasha Vita-More. Wiley & Sons, Inc, 2013, pp. 317-326.

Subba, Nikhil. “Elon Musk’s new co could allow uploading, downloading thoughts: Wall Street Journal.” Reuters, 27 Mar 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-musk-neuralink/elon-musks-new-co-could-allow-uploading-downloading-thoughts-wall-street-journal-idUSKBN16Y2GC. Accessed 21 Feb 2021.

“Years and Years: Series 1 (2019.)” Rotten Tomatoes, 2019,https://www.rottentomatoes.com/tv/years_and_years/s01. Accessed 26 Feb 2021.

[1]The terms “transhuman” and “posthuman” are often confused. While transhumanism refers to ideologies of human enhancement through science and technology, posthumanism is a philosophical praxis that critiques the Western intellectual traditions of humanism and anthropocentrism. Both transhumanism and posthumanism share a common interest in the ontological dimension of technology, but transhumanism is centred upon augmenting the human condition – while posthumanism is broadly invested in dismantling human exceptionalist discourse by drawing attention to humankind’s embroilment in an extensive network of relations with more-than-human entities, processes, and interlocutors.

Daisy Reid is a graduate student in Comparative Literature at the University of Southern California. Her research interests include speculative and science fictions, critical plant studies, posthumanism, (feminist) materialisms, and the Environmental Humanities. Her current work focuses on SF depictions of plant life and fungi in their manifold imbrications with issues of gender, sexuality, erotics, and desire.