Over the next few weeks, I am going to share several projects produced recently by my amazing USC students! Today, I am showcasing the work of Emilia Yang, who is a PhD candidate in the Media Arts = + Practice program in the USC Cinema School. Students in this program have to demonstrate cutting edge skills as media producers but also the capacity to think and write theoretically. My role in this program is to teach a course which combines media theory and history and is organized around issues of medium specificity. Yang chose to write her final paper exploring some of the issues raised by one of her own recent media projects, and I felt the paper was a great illustration of what is emerging from this innovative program. I was also interested, given last week's conference at MIT revisiting the original From Barbie to Mortal Kombat event, that she was engaging so productively with Marsha Kinder's Runaways and Brenda Laurel's Purple Moon games, both of which featured heavily at that event.

Downtown Browns: Interactive Web Series, Intersectionality and Intimacy

By Emilia Yang

The context of this work is the United States of America. 2016, the year in which Donald Trump ran for the presidency of the United States under a white supremacist, nationalist, racist, xenophobic and misogynistic campaign, and won. White supremacy and patriarchy have always been around, displaying racism and gender specific violence in all aspects of the US society, but the main focus of this essay is media. We are aware that these attitudes have characterized Hollywood ideologies since DW Griffith’s Birth of a Nation (1915). Various scholars have described, named and deconstructed the portrayal of women in film and various form of stereotyping of minorities in films¹. Recently, this imminent ideology has been made visible and contested in Internet popular culture under the hashtag #OscarsSoWhite, calling attention to the lack of representation on screen and behind the camera as well as the quality of the stories represented². Other forms of media such as television and videogames also show a systematic over-representation of males, white and adults and a systematic under-representation of other groups (Williams et all 2009).

Even though there have been valuable efforts to diversify Hollywood and other forms of media, as an academic, media creator, advocate for social justice, anti-discrimination and diversity (for lack of a better word), and latinx woman with an intersectional identity, I have tried to author media and media criticism about the things I want the most and experience the least, a type of media and analysis that centers marginalized minority groups and their experiences, questions dominant narratives through alternative voices, and sees the World with a historicized memory, informed by inequalities of power and knowledge.

For these reasons I allied with a team of radical women of color from various backgrounds and creative practices (game design, gaming, tactical media, documentary, social criticism) based in Los Angeles to produce an interactive series called Downtown Browns, winner of the “Diversity Challenge” organized by Tribeca Film Festival, Interlude and Games for Change. The three episodes series highlight the decisions faced by women of color in Los Angeles. Our themes were directly drawn from issues discussed during the presidential campaign. They are an homage to the families separated by deportations, to those vilified by islamophobia and to those who hit glass ceilings because of the color of the skin, highlighting their achievements (see section where we review some events that motivated each episode theme). Each episode follows a different storyline, showcasing a bright woman of color making their way through a unique situation as presented in the log line:

“Interactive decisions, mini-games, and perspective shifts are utilized to build an intimate understanding of the complex dynamics at play in city life”.

We took care of casting and writing diverse characters, and perhaps more importantly, we also made an active decision to try and build an all-women-of-color-crew, knowing that our collective sensibilities and experiences would strengthen the diversity of perspectives represented in the series.

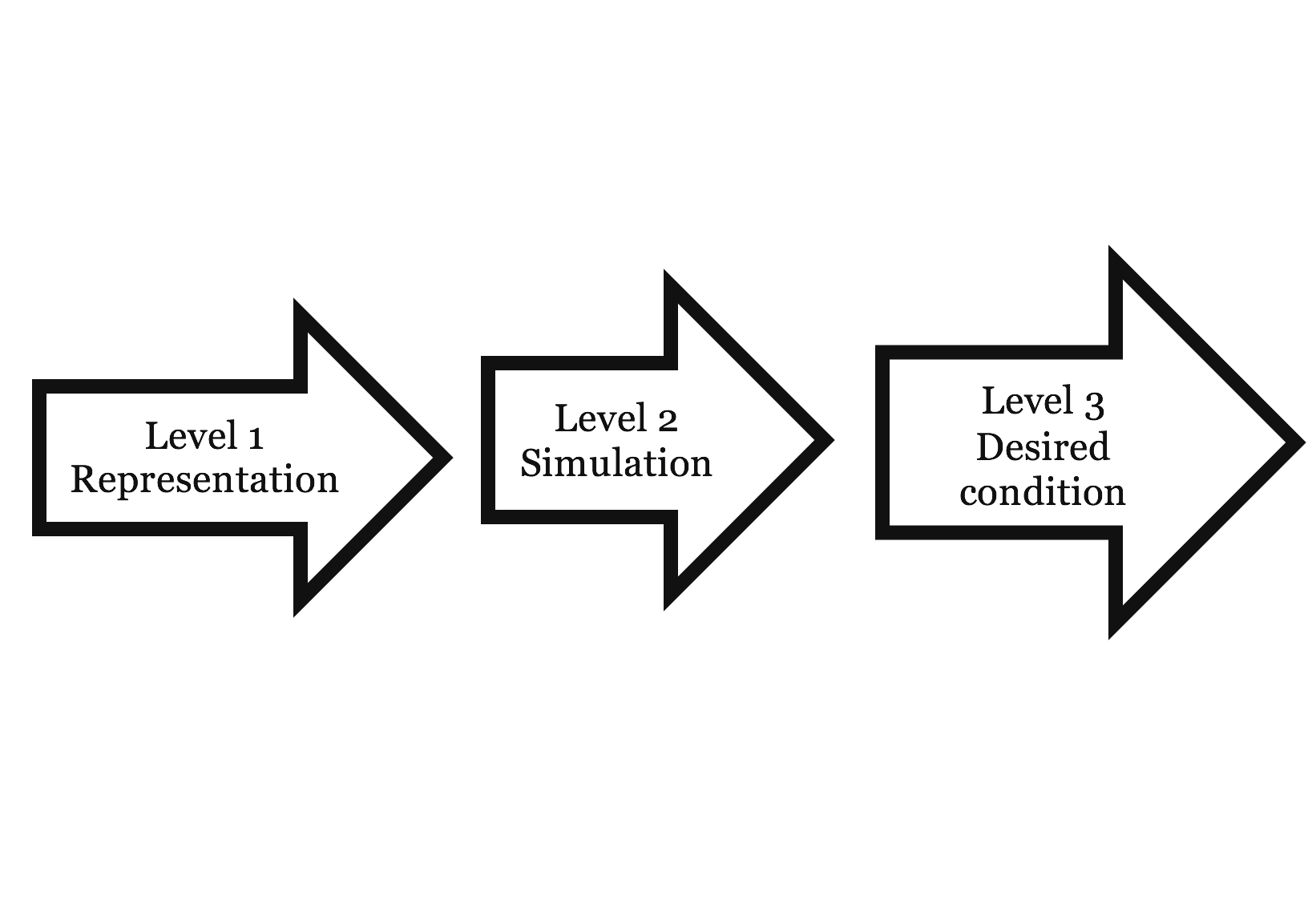

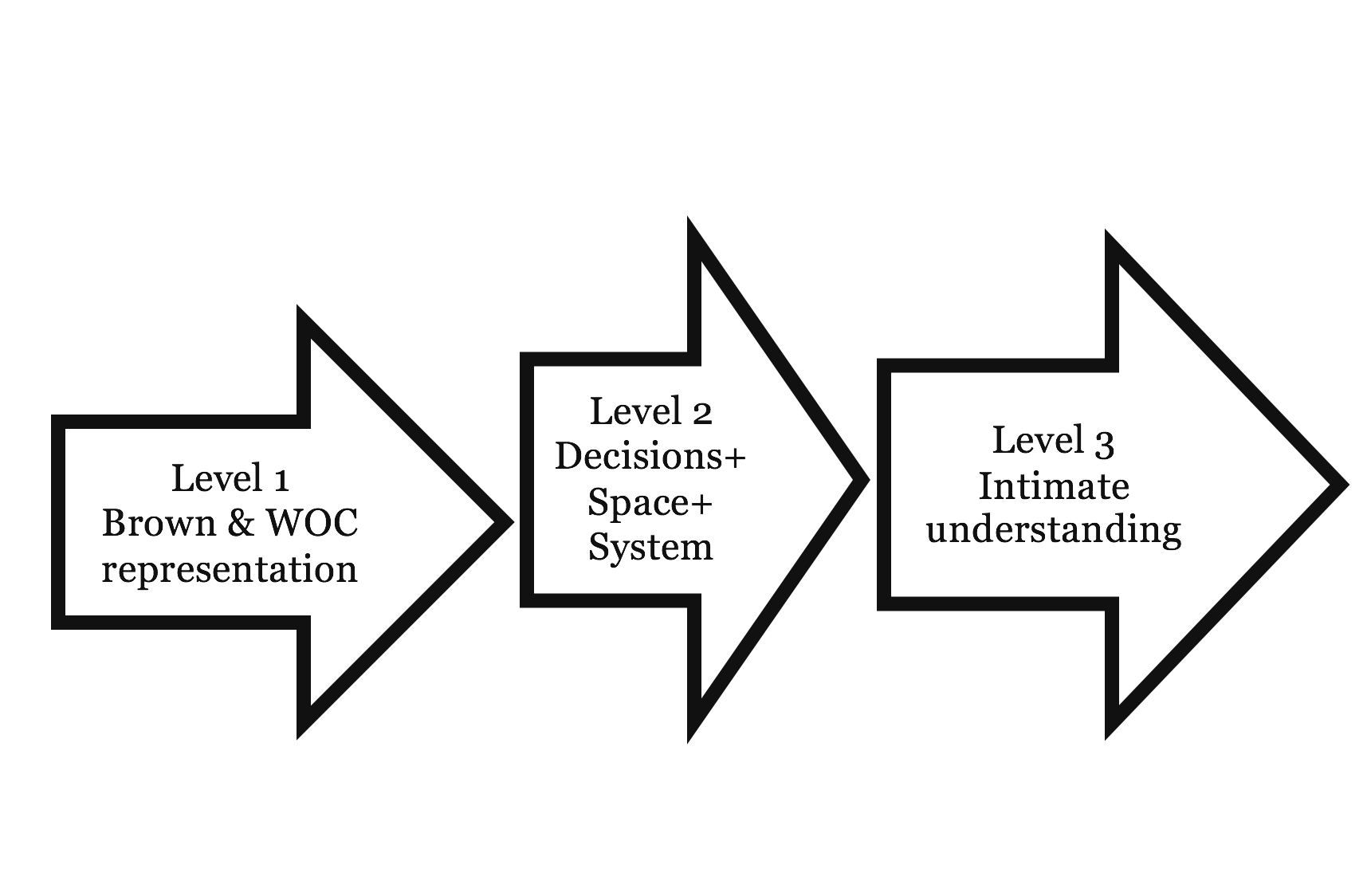

The main goal of the series was to produce a thoughtful interactive film experience that promotes intimacy and understanding with women of color. In this article I am interested in using the series as a way to discuss the potential of interactivity as a medium to accomplish this goal, and our thought process while crafting fictional representations of women of color. In order to accomplish that, I have set out in this paper to consider how to elaborate a critical analysis of interactive films that will simultaneously pay attention to what is represented in them, how they operate, and what they are intended to do. To develop this approach, I follow Gonzalo Frasca’s approach in Videogames of the Oppressed in which he states that simulation authors (game and toy designers) - and as I argue in this case interactive film makers - are ideologically responsible for the creation of three levels of evaluation. The ludus creator not only has to design the rules that make the simulation work (paidea rules), but also defines what is the ultimate goal of the game (ludus rules)³.

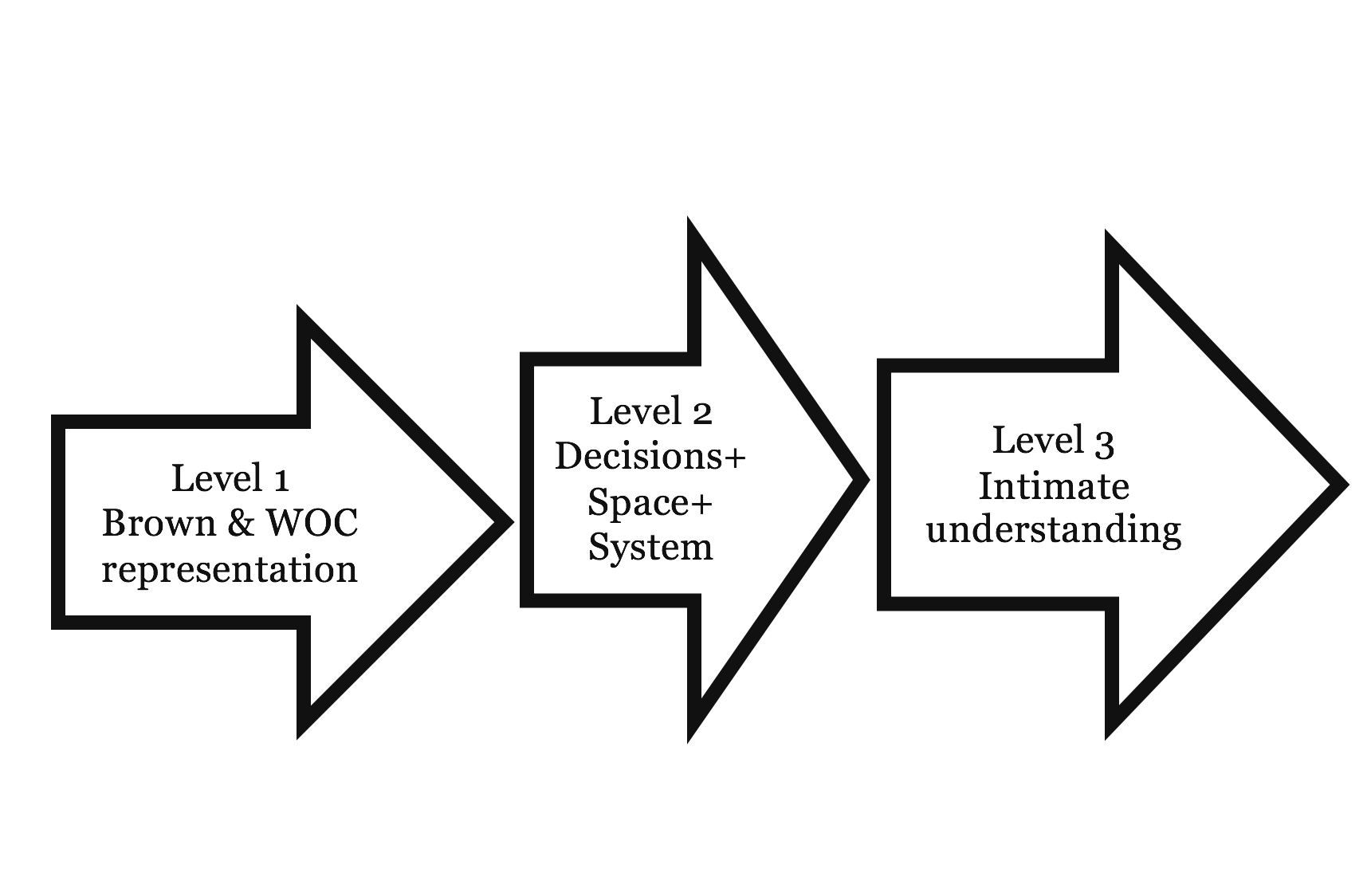

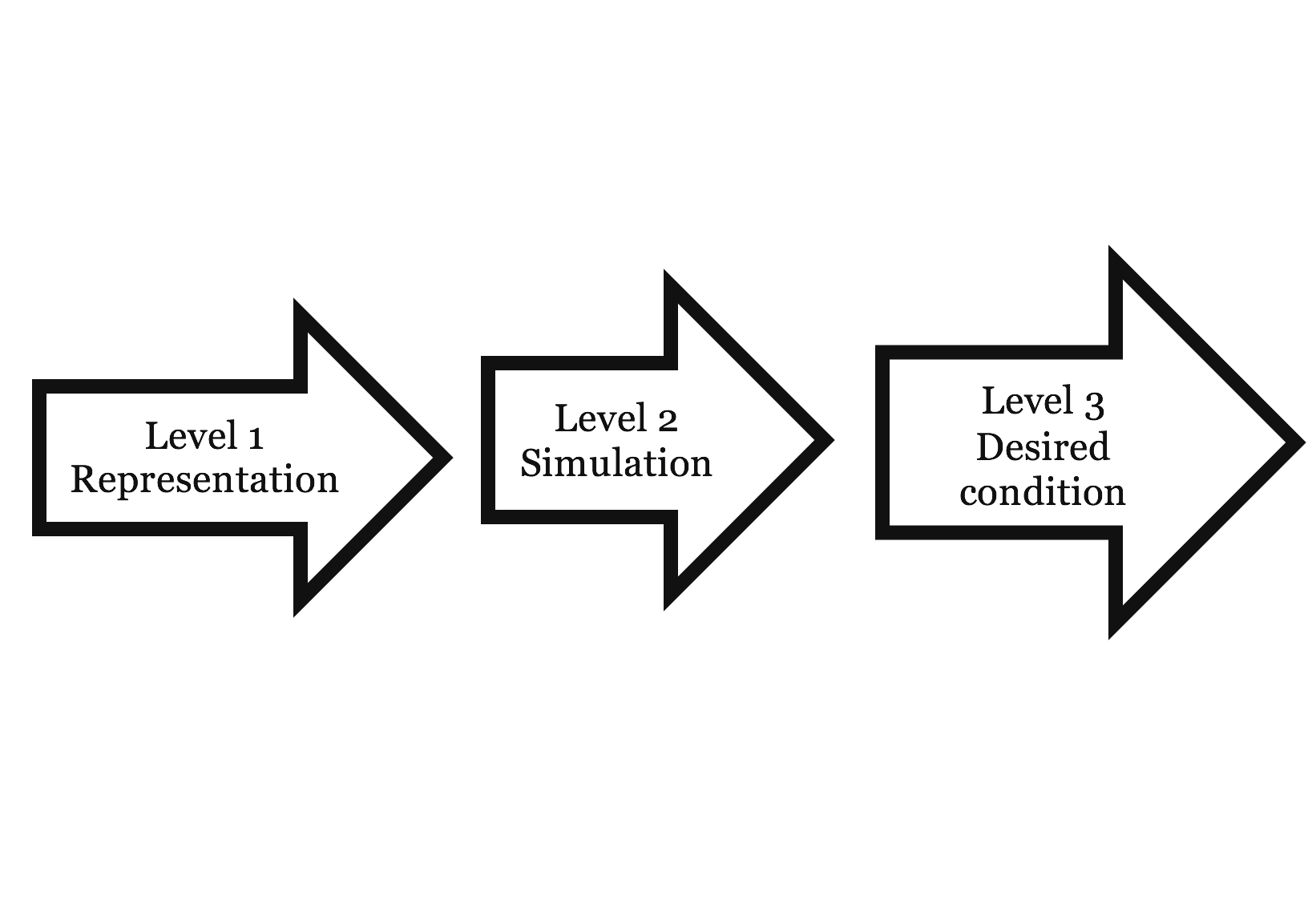

The first level is representational and Ludus incorporates two extra ideological levels. Level 1 - It is related to scripted actions, descriptions and settings and is shared with traditional storytellers.

Level 2 - It has to do with the rules of paidea, the rules that model the simulated system.

Level 3 - The third level is the ludus rule. It states what is the goal of the ludus and defines a winning, and therefore a desirable, condition (Frasca 2004:47).

Frasca uses these categories as a framework to analyze The Sims. In order to elaborate a critical analysis of Downtown Browns, framed as an interactive film series that shares characteristics with videogames, I will divide my analysis in these three levels, considering what the project represents, simulates and is intended to do. The first section discusses the motivations and implications of the use of the identity marker of ‘Brown’ as an overarching identity of women of color. I ask: What does it mean to use interactive media to explore the lives of women of color? How do you represent this complex association in a responsible way?

The second section discusses the simulations enabled by the medium. Here, I will attend to classic debates in game studies between agency and structure, focusing on how limiting the agency in the player achieves a double function in our case: to do a spatial exploration of the characters’ environment and to build an argument about structural issues. The third section discusses the desired condition (our goal), framed as the fostering of intimacy to construct an alliance with women of color. I articulate an argument on the role of ‘intimacy’, instead of the commonly deployed ‘empathy’ in media for social change, as a form of relationality that could foster consciousness raising with equal footing in the midst of antagonistic relations among races, classes, and genders. I sketch here a theory of intimacy as a form of proximity that requires identification, acknowledgment and allyship. Framed as a political gesture, I draw from political theorists to talk about this move. In a revised version of this essay, a fully historicized account of the emergence of the discourses of empathy around interactive media and intimacy in sociopolitical contexts discussed in the paper would be necessary. The purpose here is merely to outline what are potential fields of inquiry, and the potential benefits of thinking across them. Before I proceed, I will state the relationship between interactive film and videogames, as a justification for using video games theorizations to approach interactive film analysis.

Interactive film and games

Interactive media encompasses various forms of information display and storytelling, and usually refers to artifacts on digital systems that respond to users actions by presenting linked content such as text, moving image, animation, video, and audio. Interactive media has been theorized as a family of evolving forms of narrative media with previous mediums such as literature (Aarseth 1997) and theatre (Laurel 2014). Meadows defines interactive narrative as a time-based representation of character and action in which a reader can affect, choose or change the plot (Meadows 2002). Commonly known forms of interactive media are interactive narratives, websites, films, documentaries, video games, and virtual reality experiences.

Janet Murray in Hamlet on the Holodeck (1997) describes the computer as a medium that allows the expansion of storytelling towards new expressive possibilities. Her analysis covers video games along with other digital artifacts such as hypertext, web series and interactive chat characters. Even though many game critics are against the notion of lumping interactive films and games together (Adams 1995) since the hard rails of the plotting can overly constrain the ‘freedom, power, and self-expression’ associated with interactivity (Adams 1999 cited in Jenkins 2004) (Jenkins 2004), others state that the insistence on both similarities and differences between games and movies is growing shriller, in both popular press and cultural theory, as the convergence between these two forms increasingly appears inevitable (Kinder 2002:119).

The idea of interacting with media content, could be traced to the 1966’s Francois Truffo’s film version of Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, in which Linda interacts with the Family Theater, a TV program. We see her invited to participate with the prompt “Would you come play with us?”. Her answers to the questions the characters on the screen pose to her become part of their conversation. Even though this interaction is staged, it proves how the idea of interacting with the content we watch was already taking place at the time.

https://youtu.be/T0bVqgBSZHk?t=837

Fahrenheit 451 (1966)

The increase in the availability and use of video online in recent years has made it easier for creators to develop interactive films. An example of this is Eko, the platform in which Downtown Browns was developed. The company website describes their labor as “pioneering a new medium where viewers shape the story as it unfolds. The result is streaming digital interactive video that allows our viewers to affect, control, and influence narrative live-action entertainment.” As the description of Eko’s platform evokes, interactive film, in a choose-your-own-adventure film style, claim to give the audience an active role in the construction of the plot. I will further discuss this notion, and our use of agency, in the section on simulation. In the following section, I discuss why and how we are centering women of color in the series.

Level 1: Representing an intersectional approach of Brown articulation

Downtown Browns is part of a recent movement of media made by women of color of intersectional identities that have emerged in United States’ popular culture as diverse creators have had more access to tools and audiences. As Viola Davis stated, “the only thing that separates women of color from anyone else is opportunity” (Viola Davis, 2015). An inspiration to Downtown Browns and a common reference is The Mis-Adventures of Awkward Black Girl and Insecure, comedy web series created by and starring Issa Rae as J. Another similar series is Brown Girls, a web-series centered on the friendship between two women of color. In order to consider what it means to explore the lives of women of color through an interactive film, this section discusses what women of color theorists have said about the particularities of a shared subjectivity. It also considers the complexity and challenges we faced when trying to represent that subjectivity, highlighting bell hooks’ problematization of racial representations, a concern of being dressed up and dumbed down for mainstream consumption.

The articulation of a women of color subjectivity traces back the response to essentialism in white feminism, articulated by various of feminists of color delineated by Chela Sandoval, in her landmark essay “Third World Feminism in the US” (1991). Even though I believe most our team would call ourselves postcolonial feminists, in our current context we identify as women of color because the “peculiar brand of U.S. racism” (Alexander and Mohanty 1997) that characterizes our experience in this country. Sandoval sees women of color as embodying a type of ‘differential consciousness’ that engages other oppositional ideologies selectively and weaves “between and among them” in a tactical way (Sandoval 1991). Anzaldua identified this coalition as one of women who do not have the same culture, language, race or ideology, but are capable of having a collective struggle. She argued that the recognition, visibilization and mobilization of this tactical subjectivity, through writing and media creation, is a form of political work that inverts cultural norms.

Acting in similar fashion of both weaving, presenting and mediating the women of color subjectivity, the series presents itself as a collection of multiple intersectional consciousness: women, queer, Latinx, Middle Eastern and Black. This process is represented in the multi-diverse composition of our crew and through the development of our characters, Miranda, Fati and Yetunde as you get to know each character, their motivations in life, and their relationship with others and their cultural differences. Miranda, the protagonist of the first episode, is a smart Chicana who is accomplished in school. While exploring Miranda’s world you see many traces of latinx, and specifically Mexican-American (Xicana) culture. She talks about her economic struggle, her side job, her “quinces” dreams and the role of her family.

Fati is the protagonist of the second episode and she is a Middle Eastern Muslim nurse student who wears a headscarf, speaks Farsi, and loves music. Both of them speak in other languages sporadically, which we decided to use to place the viewer in a discomforting position.

Yetunde, our third protagonist, is a pop culture enthusiast, certified nerd, and young black queer woman who advocates for a social media safe space for WOC. Yetunde’s project is Queen.ly an app made specifically for women of color that both Miranda and Fati use in Episode 1 and 2.

This intersectionality allowed us to represent multiple levels of oppressions: state, cultural, professional and social (discriminatory encounters interactions between white and brown characters, and brown and brown characters across both genders). For example, Fati in episode two encounters a recent feminist (Trish) who is discerning how to help her because she considers she is “oppressed” by wearing her headscarf. We hear Trish comment: “I would love to talk to her about feminism, but where?” (See Fig. 6) Hearing Trish assume Fati is not a feminist, and has no choice but to follow traditions that are against her interests as a woman, demonstrates how an intersectional representation of women of color is required, since not all violence comes from men, but also from white women.

Furthermore, the series does not negate the violence that also exists within interactions between women of color, since Fati encounters another women of color, Tay, and Tay judges her (Fig 7). Anzaldúa has discussed solidarity within Xicana culture “To be close to other chicana is like looking on the mirror” (1987), as well as Audre Lorde in Sister Outsider in which she expresses that “the harshness and cruelty that may be present in black female interaction so that we can regard one another differently, an expression of that regard would be recognition, without hatred or envy” (1984).

In episode three, we also show how complicated relationships can be among people of color of different genders. When Yetunde talks to Darren, the other black person in the office, he thinks Yetunde “blames everything on being black,” which we characterize as "Mansplaining" 4 (See Fig. 8).

The representations of the three characters shows the nuances and the experiences that divide them from each other according to their own culture and gender specific intersectional identities; examining the incidents of intolerance, prejudice and denial of differences. We also expand and recognize their shared experience as social and systemic, trying to reframe experiences that are often perceived as isolated and individual. By doing this type of media, we are trying to bridge between the spaces we inhabit, while centering women of color, similar to the move made by this bridge we call home radical vision of transformation, in which Anzaldúa and Keating (2002) envision new forms of communities and practices inviting both women of color and white people to discuss their collective visions.

Remarkedly, we highlight bell hooks’ questioning the move to represent difference in mass culture. She states that if the desire for contact with the other -which she sees as rooted in the longing for pleasure from white culture- can act as a critical intervention that challenges and subverts racist domination is still an unrealised political possibility:

I talked to folks from various locations about whether they thought the focus on race, otherness, and difference in mass culture was challenging racism. There was an overall agreement that the message that acknowledgement and exploration of racial difference can be pleasurable represents a breakthrough, a challenge to white supremacy, to various systems of domination. The overriding fear is that cultural, ethnic, and racial differences will be continually commodified and offered up as new dishes to enhance the white palate- that the other will be eaten, consumed, and forgotten (1992).

hooks states that we cannot take these representations uncritically and I agree with her. We further attempt to address this by limiting the degree of agency we enable the users to have, which I will discuss in the next section.

Level 2: Simulating agency and structure

“A long time ago there were no toys and everyone was bored. Then they had TV, but they were bored again. They wanted control. So they invented video games”

(Kinder 2000).

It is a common misstatement that videogames are about user control. Janet Murray, talks about the agency granted by interactive media as the capacity of the medium to allow the user to perform actions that affect the represented characters, “the satisfying power to take meaningful action and see the results of our decisions and choices” (1997:24). For her, one of the main pleasures of digital artifacts is discovering the possibilities of the system through manipulation. Similarly, Laurel has stated that computers’ “interesting potential lay not in its ability to perform calculations but in its capacity to represent action in which the humans could participate” (Laurel 1993). Frasca (2004:38) cites Aarseth (1997) explaining that the manipulation of the system is not trivial since it requires that the player get engaged into a process of decision-making that will affect her experience of the system. For Frasca the process of manipulation is what renders possible the interpretation of the multiple facets of a simulation. The participative gamey aspect of the series, the rules of paideia allows for the user to simulate of agency via emotional choices, explore intersubjectivity through perspective switches, and the exploration of the main characters’ environments as spatialized storytelling. As I will develop in this section, it is only to demonstrate how little choice WOC have in most situations.

Simulating agency

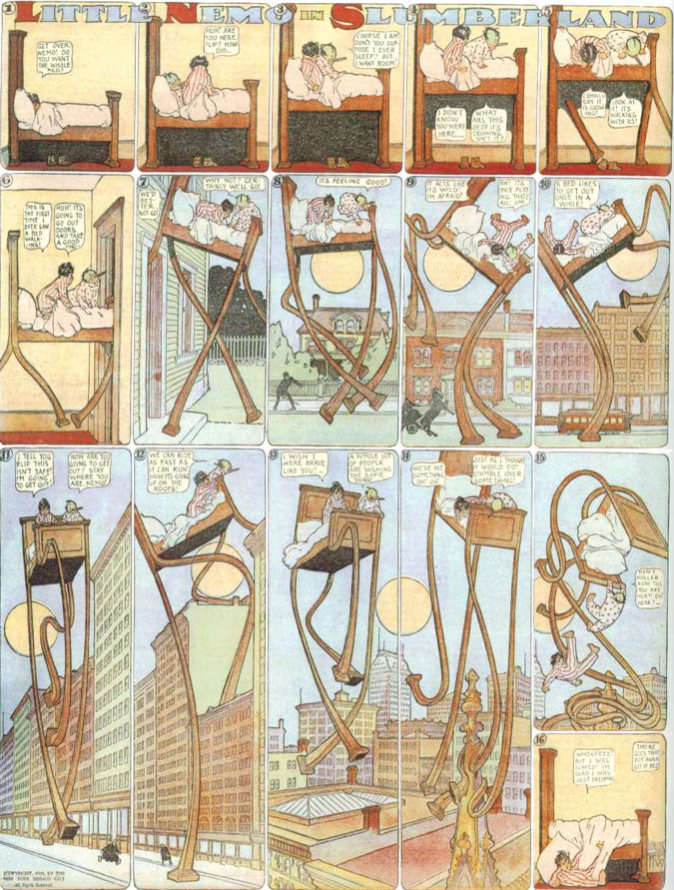

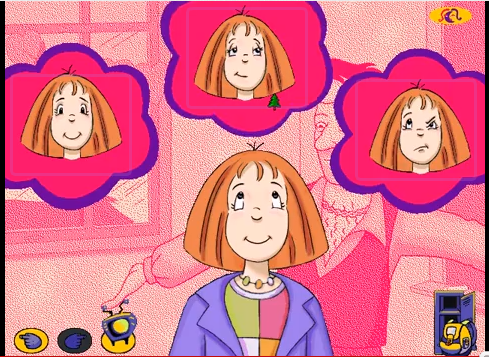

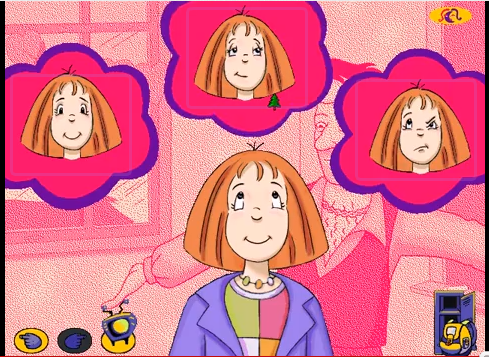

A common reference for our series, with similar interactive decisions, were Brenda Laurel’s Purple Moon games, built based on gender difference and self-construction. These charming experiences were part of the Games for Girls Movement that started more than 20 years ago and brought to the game studies discussions by Jenkins in From Barbie to Mortal Kombat: gender and computer games (2000). Tonia, our uniting force and co-creator, mentioned them in an interview as an inspiration and her first “girl game”. Purple Moon games portrayed a suburban white junior high girl’s experience that allowed players to choose the emotional states that Rockett, the main character would make in order to relate with others, framed as a friendship adventure (See Fig 9).

Similar to Purple Moon, episodes one and three of our series invite people who might not be familiar with the realities of women of color to participate in helping the character decide the emotional reactions they will have in the face of adversity as well as more mundane situations as they move through the day. In this sense, the series is pedagogical in that it was designed to be inviting for non women of color to approach our perspective and experiences. However, we are sensitive to how women of color are often expected to act as bridges and translators, bearing the responsibility of educating white America about systemic racism, misogyny and other forms of oppression. The series gives protagonists the choice to refuse bearing this burden at all times. As Donna Kate Rushin’s Bridge poem eloquently states “I'm sick of seeing and touching. Both sides of things. Sick of being the damn bridge for everybody” (1981). In episode three, Yetunde must decide at times whether to let things slide or to correct or confront people and their micro-agressions. At times, refusing to explain why something might be racist is the only way she can sustain her energy and focus on her goals.

Intersubjective experiences

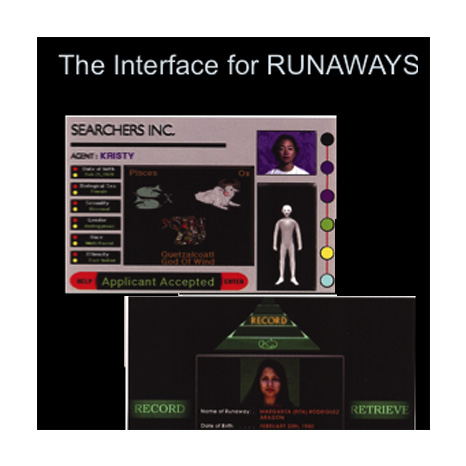

Marsha Kinder’s Runaways project is another relevant example, since it gave users the ability to select the identity of its avatar, which determined how other characters respond to it based on ethnic difference. The developers of this experience saw it as an opportunity to deal with the social consequences of these choices and the issue of stereotypes and gender play. The game placed you in the uncomfortable role of being treated as a stereotype and having other characters make all sorts of false assumptions about you (Kinder 2000) (See Fig. 10).

Downtown Browns does not allow user to customize their avatar, since for us an accurate representation of women of color is eminently needed, as represented in level one of this analysis, but we make use of switch of parallel perspectives in episode two (See Fig. 11) in order for people to understand how stereotyping weighs into discrimination in daily life. In this episode the user gets to hear what others are thinking of Fati, while they can also hear what Fati is thinking about them. There is almost no dialogue in Episode 2, but the internal dialogues show how some of the bystanders exotify, some sympathize, and others fear Fati, while she is missing her family or documenting her experience. Users choose which perspective prevails by curating their own personal experience of the film.

Spatialized storytelling

The series is also meant to be pleasurable experience for people of color who play them. Some of the interactive decisions allow POC to identify aspects of life as a women of color by exploring their space with things we find interesting, cool, necessary and aspirational (See Fig. 12). The interactive decisions in which the user gets to explore content in a spatialized way are a form of “environmental storytelling”, as described by Jenkins, “game designers don’t simply tell stories; they design worlds and sculpt spaces… and they fit within a much older tradition of spatial stories, which have often taken the form of hero’s odysseys, quest myths, or travel narratives” (2004). In this case the sheroes are women of color and you explore their closest intimate environments and you are able to identify specific things of their culture. Ian Bogost refers to this as “emotional vignettes” that characterize an experience and is often used to inspire empathy rather than advancing the narrative (2011). Later in the essay I will take issue with empathy.

Adding to the interactive decisions, the narrative branching structure offers multiple endings in each episode, but Downtown Browns refuses to offer happy endings in which characters singlehandedly make their own destinies. Instead, we are confronted with how, despite character’s reactions and decisions, the things that happen to them are mostly beyond their control as they respond to broader systemic problems in our society. This tackles issues like blaming WOC for their impossibility of advancing, “she is not working hard enough” or “why didn’t she just do this?” and focuses on understanding both their underlying motivations of WOC, the constant quickness needed to react in the different systems of discrimination that take place and whose role is it to call out racism.

Sherry Turkle, as cited by Frasca (2004), identifies three attitudes towards simulations: “simulation denial” which is a rejection of simulations because they offer a simplified view of the source system and “simulation resignation”, that accepts them because the system does not allow to modify them. However, Turkle imagines another possible kind of relationship, “it would take as its goal the development of simulations that actually help players challenge the model’s built-in assumptions. This new criticism would try to use simulation as a means of consciousness-raising. (Turkle 1995). Even though one is left with a feeling of impotence, by acknowledging that the system is unfair to each one of the characters we use simulation as a means of consciousness-raising. We tried to show the system whose core assumptions are not visible if you do not experience them as a WOC. Turkle states that understanding the assumptions that underlie simulation is a key element of political power. When simulations are sufficiently transparent, they open a space for questioning their assumptions.

Level 3: Desiring intimacy against empathy

“Flush yrself down the toilet if you think you’ve ‘learned empathy for trans women’ by playing dys4ia.”

Ann Anthropy on Twitter

Since our goal was to promote intimacy and understanding with women of color as a means of conscious rising (ludus rule), through accurate and positive representations as well as simulation by showing the system of oppression, I will make an argument for the reasoning behind our use of intimacy instead of empathy. First, I will define empathy and trace some of its philosophical underpinnings, then I will present how it has been used in games and how intersectional creators have challenged this notion. Finally, I will discuss how intimacy, as a process of feeling-with rather than feeling-for, serves as the purpose of conscious raising and bridging of cultures that we entail to do in the series.

Commonly understood, empathy “refers to the process of experiencing the world as others do, or at least as you think they do. To empathize with someone is to put yourself in her shoes, to feel her pain” (Bloom 2014). Empathy as part of identification traces back to Adam’s Smith and David Hume’s (1896) use of sympathy as a necessary mode of identification between people, predicated upon our ‘natural’ ability to read the signs of the other’s affect, in which they base many of their ideas of liberal governance. Others have elaborated in it’s role in the construction of various forms of power-relations, as a “technology of race and gender,” and its role in new evangelical social movements such as abolitionism and missionizing (Rai 2002). Some researchers see it as a physiological endeavour, ‘seeing like others’, others see it as an emotional one, ‘feeling like others’, and others see it as cognitive process, that entails ‘thinking like others’. Michael Bloom states that most of the discussion of the moral implications of empathy focuses on its emotional side. He also states that empathy it is not the only force that motivates kindness, and people naturally have less or more empathetic abilities, and that does not conflict with their sense of justice. He makes an argument for rational thinking instead of empathy since for him empathy is narrowed, biased and individual.

In the gaming world, the term “empathy game” refers to a speedily expanding genre of games “designed to inspire empathy in players” (D’Anastasio 2015), which in turn are part of a broader genre identified as “serious games” or “games for change”. News outlets and game conferences have covered their arrival on the market with enthusiasm and optimism (D’Anastasio 2015). This new category of games ranges different forms of interactive experiences, and supposedly are intended to make allies out of gamers, since they mostly focus on developers’ personal experiences, placing the player through the developers’ more difficult life milestones. D’Anastasio cites as examples of this are dys4ia an 8-bit flash game that Ann Anthropy made to evoke her experience with hormone therapy, and other such as Depression Quest. Anthropy, as stated in her tweet and blog posts, is now challenging the idea that a digital game can confer an understanding of her lived experience, marginalization, and personal struggle. She states that being an ally takes long work. Other game developers, such as Colleen Macklin, have discussed the perils of trying to convey empathy through games; because some games have shown through their mechanic that agency is all is needed for people to change their circumstances (Parkin 2016). Ian Bogost in How to do things with videogames devotes a chapter to empathy stating “one of the unique properties of videogames is their ability to put us in someone else’s shoes” (2011).

Bringing back hooks’ fear of “eating the other;” Downtown Browns seeks to promote another way of relating with us women of color, which requires the work of both groups’ people of color and white people, not just emotional tourism or empathetic arousal, nor calling again for centering the white dominant. Samia Nehrez (1991) as cited by hooks (1992) talks about how decolonization can only be complete when it is understood as a complex process that involves both the colonizer and the colonized. This reframing requires another type of labor, one that is not constituted in further displacement, and one that does not remove the body and consciousness of women of color of the frame, but bridges between our experience and others’ while acknowledging this bridging needs both sides.

Creating Downtown Browns allowed us to think, what would be a good form of encounter? We required to frame it as another form of identification and recognition that entails a more equal grounds. Empathy gives priority to the viewer, assuming that the other is in disadvantage. Even though in the series we share vulnerable situations and emotions, we do it with the acknowledgement that is under our own terms. Multiple times we have heard after people play the series, that they want to know what happens to the characters. Lauren Berlant states that intimacy “involves an aspiration for a narrative about something shared, a story about both oneself and others that will turn out in a particular way” (1998). In an intimate environment I am acknowledging you and allowing you to know me, but you have to do an active decision to value me, not talking for me, not try to think you have solutions for me. Only in those instances we can negotiate a shared space and shared life. Even though we are aware this might not always be the case.

As outlined in the introduction, I focused this essay on the potentials of interactive film as a critical medium and to craft an analysis that simultaneously pays attention to what is represented, simulated and hopefully accomplished. I trace historical references of brown articulation from radical women of color in the United States that inspired us, as well as historical uses of computer simulation for demonstrating experiences of others crafted by female creators as highlighted by De Laurel’s and Kinder’s work. Going back to the graphic I presented earlier of Frasca’s model, I map the relationship the series represent between form and content, simulation and experience, as well as the implicit theories about ideology, representation, identification, and interactivity that shaped the choices we made as creators.

Reading the graph the other way around from right to left, intimacy is fostered via the simulation of decisions women of color make, that allows others into our space and shows them how the system operates in relationship to our specific race, gender and sexualities, by conceiving a thoughtful representation of women of color’s multiple subjectivities. By opening these experiences and showing these spaces to other groups of people we hope we foster and intimate understanding, a shared story, an initial conversation about the negative and positive things we experience in U.S society. I leave the arrows as a continuum, since I must include the conversations and discourse (such as this) the series have allow us to have as part of its’ work. As Jeff Watson, theorist, maker and friend told me one day, “games and media are just a pretext for context”.

As I stated above, intersectional creators cannot promise and should not be interested in people inhabiting their subjectivities, nor should they try for dominant groups just to empathize, and neither should they take the burden all by themselves. Instead we should try to engage meaningfully with each other’s lives, invite other people of color and white people to walk with us, to be next to us, to be real allies. It is by listening, by working together to change the type of socializations imposed by media, by building solidarity and respecting difference that we will accomplish any progress or social change. I extend special thanks to Henry Jenkins’ thoughtful and constructive comments and to my Downtown Browns squad that with multiple conversations around these topics have challenged my thinking and approach to socio-political and cultural issues.

About the author

Emilia Yang is an activist, artist, and militant researcher. Her work has been interconnected with digital communications, performance, and public art. Her research focuses on participatory culture and its relationship to media, arts, and design. Yang is currently pursuing a PhD in Media Arts + Practice at the School of Cinematic Arts at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. She is interested in how transmedia storytelling and postcolonial new media practices can foster social change and civic engagement. Her art practice utilizes site-specific interactive installations, documentaries, fictions, games, performances, and urban interventions to engage participants in political action and discussion. She is a HASTAC 2015-2016 Scholar and member of Civic Paths at USC.

Footnotes

- (Mulvey, 1989; Hall 1997; hooks 1992, 1996, Kareithi, 2001; Wilson and Gutierrez 1985, Roman, 2000; Chavez, 2013, West, 1990 - the list is extensive).

- A 2016 University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) study found minorities remain underrepresented in Hollywood on every front (nearly 3 to 1 among film leads and directors) and that audiences are seeking diverse film and television content. McNary, Dave “Hollywood’s Diversity Problem Potentially Costs Industry Billions (Study)”.

- As cited by Frasca (2004:6), Caillois (1967) uses the term ludus, the Latin word for game, to describe games which rules are more complex. Paidea and ludus could be associated with the English terms “play” and “game”, respectively.

- Mansplaining is a portmanteau of the words man and explaining, defined as "to explain something to someone, typically a man to woman, in a manner regarded as condescending or patronizing".

References

Aarseth, Espen J. 1997. Cybertext: perspectives on ergodic literature. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

Adams, Ernest. 1999. “Three Problems For Interactive Storytellers.” Gamasutra, December 29, 1999.

-------------------1995. “The Challenge of the Interactive Movie.” Lecture at Computer Game Developers’ Conference. Designer Notebook Website. Retrieved December 12, 2016. http://www.designersnotebook.com/Lectures/Challenge/challenge.htm

Alarcon, Norma. 1981. ed. The Third Women. Bloomington: Third Women Press.

Alexander, M. Jacqui, and Chandra Talpade Mohanty. 2013. Feminist genealogies, colonial legacies, democratic futures. London: Routledge.

Rai, Amit. 2002. Rule of sympathy: Sentiment, race, and power, 1750-1850. New York: Palgrave.

Anzaldúa, Gloria. 1987. Borderlands: la frontera. California: Aunt Luke Book Company.

Anzaldúa, Gloria and Ana Louise Keating. 2002. eds. this bridge we call home: radical visions for transformation. New York: Routledge.

Berlant, Lauren. 1998. "Intimacy: A special issue." Critical Inquiry 24.2: 281-288. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bloom. 2014. Against Empathy. Boston Review. Retrieved December 12, 2016. http://bostonreview.net/forum/paul-bloom-against-empathy

Bogost, Ian. 2011. How to do things with videogames. Minnesota: U of Minnesota Press.

---------------2007. Persuasive games: The expressive power of videogames. Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Burke, Yoshiko. 2004. "From the Silver Screen to Cybercinema: Conceptions of Space in Interactive Narrative Design." Proceedings from FutureHistory: AIGA Design Education Conference. Retrieved from http://futurehistory.aiga.org/

Caillois, Roger. 1967. Les jeux et les hommes. Le masque et le vertige. Gallimard, Cher.

Cassell, Justine and Henry Jenkins. 2000. eds. From Barbie to Mortal Kombat: gender and computer games. Massachusetts: MIT press.

Chavez, Leo. 2013. The Latino threat: Constructing immigrants, citizens, and the nation. California: Stanford University Press.

Cherrie Moraga and Gloria Anzaldua.1981. This Bridge Called My Back: A Collection of Writings by Radical Women of Color. Massachussets: Persephone Press.

D’ Anastasio, “Why Video Games Can't Teach You Empathy”. Motherboard. Retrieved December 10th, 2016 http://motherboard.vice.com/read/empathy-games-dont-exist

Davis, Viola, Viola Davis makes Emmys history, dedicates incredible speech to women of color. Mashable, September 20, 2015. Accessed November 20, 2016, http://mashable.com/2015/09/20/viola-davis-emmy-best-actress-drama/

Downtown Browns Website Accessed November 20, 2016, http://downtownbrowns.weebly.com/

Eisenstein, Sergei. 1974. “Montage of Attractions,” Drama Review, 77-85.

Frasca, Gonzalo. 2004. Videogames of the Oppressed. Electronic book review, 3.

Hume, David. Treatise on Human Nature. 1896 [1739]. Liberty Fund.

Hill Collins, Patricia. 2004. Black sexual politics: African Americans, gender, and the new racism. Routledge.

hooks, bell. 1992. Black looks: Race and representation. Massachusetts: South End Press.

------------- 1982. Ain't I a Woman Black Women and Feminism. Massachusetts: South End Press.

Hull, Gloria, Patricia. Scott, and Barbara Smith. 1982. All the Blacks are men, all the women are White, but some of us are brave: Black women's studies. New York: Feminist Press.

Inclusion Conference. “Variety to Host Conference on Diversity and Inclusion in Hollywood” September 26, 2016. Accessed November 20, 2016 http://variety.com/2016/biz/news/variety-inclusion-conference-pharrell-williams-donna-langley-1201870256/

Jenkins, Henry. 2004. Game Design as Narrative Architecture. First Person. Massachusetts: MIT Press. Accessed November 20, 2016 http://www.electronicbookreview.com/thread/firstperson/lazzi-fair

Jenkins, Henry. 2016. Transforming Hollywood Diversifying Entertainment. Confessions of an Aca Fan. The official weblog of Henry Jenkins. June 22, 2016. Accessed November 20, 2016

http://henryjenkins.org/2016/06/save-the-date-transforming-hollywood-7-diversifying-entertainment-october-21.html

Kareithi, Peter. 2001. 'The white man's burden'-how global media empires continue to construct'difference': global narratives of race. Rhodes Journalism Review: Global narratives of race: racism and the media worldwide, (20), 6-9

Kinder, Marsha. 2000. An Interview with Marsha Kinder. In Cassell, J., & Jenkins, H. From Barbie to Mortal Kombat: gender and computer games. Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Kinder, Marsha. 2002. “Narrative equivocations between movies and games” The new media book. Edited by Han Darris. 119-32. London: British Film Institute.

Laurel, Brenda. 2013. Computers as theatre. Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley.

Ling, Amy. 1990. Between worlds: Women writers of Chinese ancestry. Oxford: Pergamon Press.

Lorde, Audre. 1984. Eye to eye: Black women, hatred, and anger. Sister outsider: Essays and speeches, 145-75. New York: The Crossing Press.

McNary, Dave. “Hollywood’s Diversity Problem Potentially Costs Industry Billions (Study)”, Variety, February, 25, 2016. Accessed November 20, 2016 http://variety.com/2016/film/news/hollywood-diversity-report-industry-losing-billions-1201714470/

Meadows, Mark Stephen. 2002. Pause & effect: the art of interactive narrative. London: Pearson Education.

Mulvey, Laura. 1989. "Visual pleasure and narrative cinema." Visual and other pleasures. 14-26. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Murray, Janet H. 1997. Hamlet on the Holodeck. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Nehrez, Samia. 1991. The Bounds of Race. Ithaca: Cornel University Press.

Parkin, Simon. 2016. The risk of games that seek to create empathy. Gamasutra. Retrieved December 12, 2016. http://www.gamasutra.com/view/news/268266/The_risk_of_games_that_seek_to_create_empathy.php

Roman, Ediberto. 2000. Who Exactly Is Living La Vida Loca: The Legal and Political Consequences of Latino-Latina Ethnic and Racial Stereotypes in Film and Other Media. J. Gender Race & Just., 4, 37.

Sandoval, Chela. 1991. "US third world feminism: The theory and method of oppositional consciousness in the postmodern world." Genders 10: 1-24. Texas: University of Texas Press.

Smith, Barbara. 1986. The Combahee River collective statement: Black feminist organizing in the seventies and eighties. Vol. 1. Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press.

SPLC Hatewatch, Southern Poverty Law Center Website. Accessed November 20, 2016, https://www.splcenter.org/hatewatch/2016/11/18/update-incidents-hateful-harassment-election-day-now-number-701

Turkle, Sherry.1995. Life on the Screen. Identity in the Age of the Internet. New York: Simon and Schuster.

West, Cornel. 1990. 'The New Cultural Politics of Difference." Russell Ferguson et al. (eds.), Out There: Marginalization and Contemporary Cultures. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Williams, Dimitri, and Nicole Martins, Mia Consalvo & James D. Ivory. 2009. The virtual census: Representations of gender, race and age in video games. New Media & Society, 11(5), 815-834. New York: Sage.

Wilson, Clint C. and Félix Gutiérrez.1985. Minorities and the Media. London: Sage Publications.