What Kinds of Difference Do Superheroes Make?: An Interview with Ramzi Fawaz (Part One)

/From time to time, I use this blog to showcase new books released as part of the Postmillenial Pop book series which Karen Tongson and I oversee for New York University Press. As always, we are interested in hearing from writers and scholars who are doing projects which fit within the flexible boundaries of this particular series -- we are looking for ground-breaking work on all aspects of popular media and culture, work that may explore themes anchored in the past but which always does so with an awareness of contemporary developments, especially those having to do with diversity and inclusion. Ramzi Fawaz fits our notion of Postmillenial Pop perfectly, and it's been a pleasure to work with him as he has developed and published his book, The New Mutants: Superheroes and the Radical Imagination. The book has been out for only a short while and it has already generated extraordinary responses. Here are just a few:

"A powerhouse one-of-a-kind book! By charting the radical transformations of the comic book superhero in the post-war period, Fawaz brings to light the extraordinary secret history of American Otherness. Truly fantastic."

—Junot Díaz, Pulitzer Prize winning author of The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao

"I have never encountered anyone--not Art Spiegelman, R. Crumb, Douglas Wolk, Stephen Burt, or even Michael Chabon--who has addressed himself to superheroes with Ramzi Fawaz's generosity of spirit and unsatisfiable critical fervor. In this book, one is caught up in the way in which we and the likes of Superman, the Fantastic Four, the X-Men, and the Silver Surfer share a common terrain of both history and imagination. All sorts of people will bring a long-nurtured, even fetishized familiarity to Fawaz's pages, and it won't survive--the most familiar stories are, here, radically, thrillingly new."

—Greil Marcus, author of Mystery Train: Images of America in Rock 'n' Roll Music

Here are just a few of the things I admire about this book: Fawaz knows his stuff -- he combines a fan's attention to the specifics of comics history with a scholar's bent for theoretical insights especially having to do with race, queerness, global politics, and otherness. He takes his comic-book superheroes on their own terms with the right mix of playfulness and seriousness. He believes the comics of the 1960s and 1970s matter -- in part because they offered alternative conceptions of masculinity, Americanness, and sexuality, that did not bubble up into the mainstream very many places in the popular and mass media of the era. They provide us with "memory traces" of a period of profound disruption and transition. He is not afraid to discuss the progressive and even radical potentials he sees within these larger-than-life stories, as well as to explore the ways that these graphic storytellers often compromised in their efforts to tell this stories through a commercial medium. And he sees the fans and the letters they wrote to the publishers as a kind of alternative public sphere, where people are willing to play with the possibilities for difference that these comics open up within their civic imagination.

All of this makes The New Mutants a lively read and perhaps one of the most provocative accounts of popular media I've seen in recent years. I strongly recommend this book, which has implications well beyond the emerging field of comics studies, since it represents such a great model for historically grounded ideological analysis of popular culture in all of its many variations.

As I've gotten to know the author better through our interactions around the book, I have come to value his passionate insights and challenging perspectives on popular media and the scope of his interests and expertise. What follows is a guide to how and why superhero stories matter and how and why we should integrate them more fully into our teaching and scholarship.

Why study superhero comics and especially why study superhero comics now?

At their core, superhero comic books tell stories about people gifted with extraordinary (and impossible) abilities who must contend with the question of what to do with those abilities: whether to use them to serve their own interests, to benefit others, to hide them altogether, or to forward a particular vision of progress, social change, or collective governance. These stories are fantasies in the sense that they explore bodily capacities—shapeshifting, controlling the weather, rapid healing, intangibility, super strength etc.—that humans do not actually have access to, in order to both take pleasure in the imaginative possibilities of expanded ability (which, let’s face it, is just plain old fun) and to meditate on what kinds of choices people make with the powers at their disposal.

Superhero comic books then, are a living archive of our collective fantasies about a number of concerns including the nature of power (its pleasures and dangers), the meaning of ethical action and collective good, visual pleasure in witnessing impossible abilities, and the capacity to change the world. In that sense, superhero comics have a lot to tell us about the underlying desires, dreams, and aspirations that have motivated the American imagination in the 20th century; tracing how superheroic fantasy changes over time gives us insight into larger transformations in what it is that Americans fantasize about, how they struggle over competing visions of the use of power and force, and how they use visual media like comics to creatively narrate alternatives to their own conditions of existence.

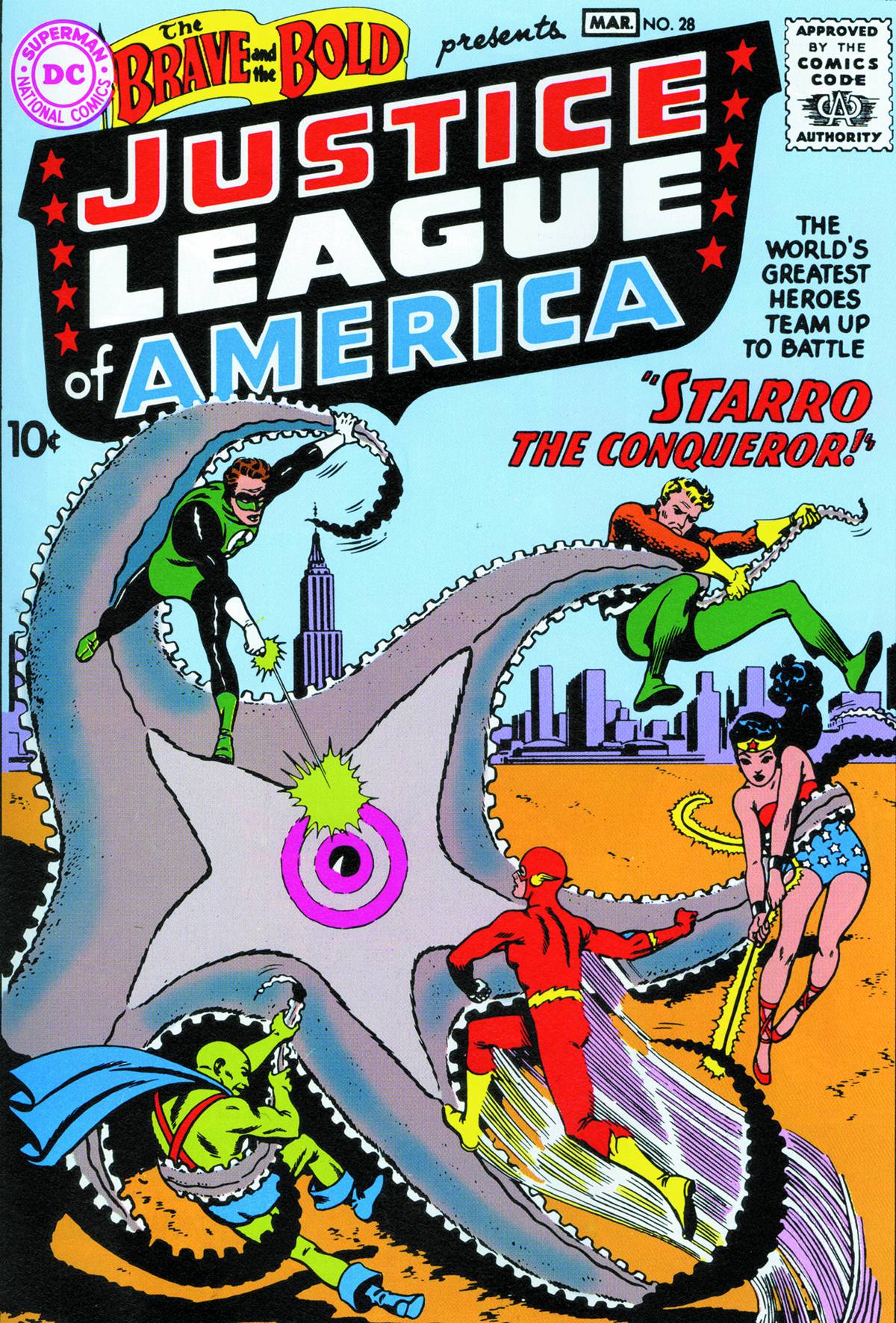

Take for example the rise of the superhero team in the 1960s compared to the popularity of singular crime-fighting heroes in the 1930s and 1940s. In the 1930s and 1940s, Americans through the Great Depression and a second World War were drawn to fantasy figures like Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, and Captain America who were gifted with exceptionally enhanced strength, speed, agility, and fighting power. These heroes used their abilities against a variety of threats to the American way of life including fascism, poverty, political corruption, and organized crime. At a moment when the twin pillars of Americanism—democracy and capitalism—were in terminal crisis, such visions of individual will power, strength, and invulnerability projected fantasies of control over one’s destiny in a world where individual Americans had lost the sense that their personal choices could make any difference in assuaging large-scale economic and political catastrophe.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, however, superhero teams—collectives of individual superheroes binding together to use their powers in the interest of global and intergalactic peacekeeping—became extremely popular; unlike the culture of bootstrap individualism celebrated in previous superhero stories, 1960s superhero comics were dominated by narratives of cooperation, shared deliberation about the nature of a common good, and collective action against threats to the survival of a variety of species throughout the cosmos. These comics tell us something about the shifting fantasies of power that Americans held across this period, including the increasing desire for new forms of collective life and innovative ways to imagine cooperative practices of global care and ethical action.

Neither the individualist superhero nor the superhero team were mere reflections of their times; rather they were extended creative meditations on what it would mean to enact, deploy, and inhabit different modes of power (whether individual will or collective action) at historical moments when those forms of power were in flux or just starting to emerge as genuine political possibilities: we might recall, for example, how in the late 1950s and early 1960s, global peacekeeping organizations like the United Nations and UNESCO, and egalitarian political movements like the Students for a Democratic Society, the Civil Rights Movement, and third world movements were beginning to provide models of what internationally oriented and democratic forms of governance could look like.

While comics reflected these realities, they also told epic tales of superheroic cooperation that unfolded over years of narrative storytelling, thereby producing extended explorations about what possibilities might unfold from the collective actions of formerly independent heroes; these stories necessarily projected a variety of possible outcomes to projects for global peace.

We should study superhero comics now because the fantasies they narrated and visualized throughout the 20th century have captured the imagination of almost every major American media outlet. While comic book characters and scenarios have appeared in a variety of American media forms since the 1960s (including the acclaimed Wonder Woman TV show, the Spider-Man and Super Friends Saturday morning cartoon shows, and the original Superman movies), starting in the late 1990s, that media influence has accelerated at an exceptional pace; even as Americans read less and less actual comics, they encounter superhero comic book characters with greater frequency and intensity in big-budget Hollywood films, web comics, video games, animated features, television series, toys and merchandise.

This suggests both the incredible durability of this particular fantasy figure, and its ability to do and mean different things in different media platforms. If for not other reason than its continued visibility and popularity, we should be curious about why this figure holds such a powerful sway over the American cultural imagination, and how its appearances in different formats accomplishes vastly differing kinds of work.

Your primary focus throughout the book is on superhero comics of the 1960s and 1970s. What’s changing about the genre during this period and why?

The 1960s and 1970s represented an extraordinary renaissance in superhero comic book production and creativity. The central creative transformation that helped catapult the superhero comic book to new heights of popularity was the intention reinvention of the superhero from a figure of white masculinity, individualism, and Americanism into a genetic and species outcast.

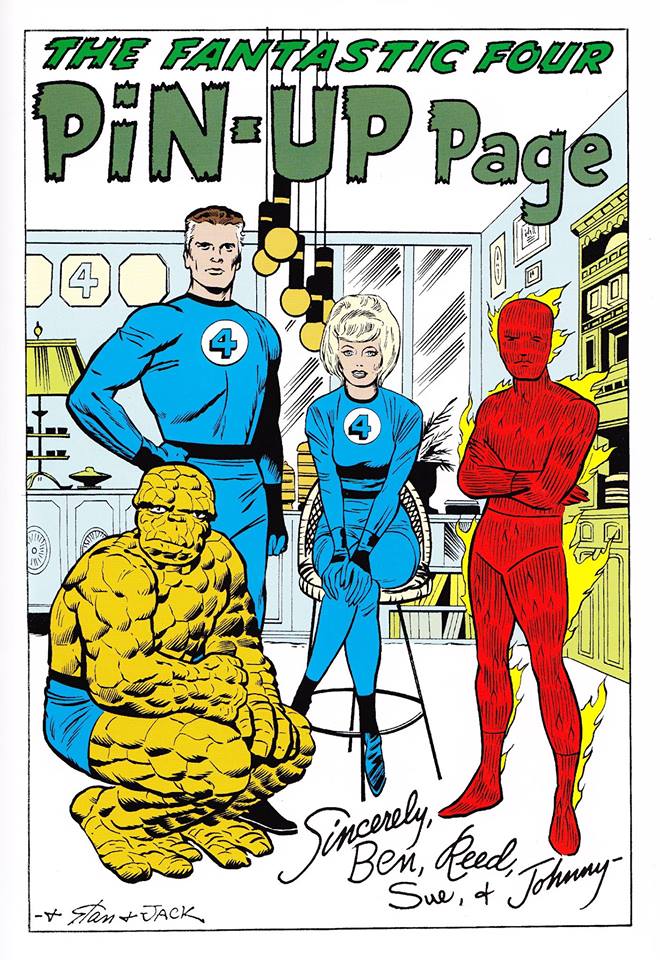

In this period, comic book creators began to introduce a new pantheon of heroic figures who comprised a generations of mutants, freaks, misfits, monsters, aliens, and cosmic beings who questioned all kinds of assumptions about what it meant to be an ordinary human, or to be an “exceptional” heroic being. These characters—like the molecularly transformed members of the Fantastic Four, or the mutant X-Men, heroes gifted with abilities due to a genetic evolution in their DNA—articulated the value of difference itself, rather than simply exceptional humanity. They modeled surprisingly complex strategies for negotiating a world filled with ever more diverse superheroes, human allies, alien species, and cosmic beings.

In my book, I argue that this creative shift radically altered the fundamental visual and narrative structures of superhero storytelling: this included the visual scaling upward of superhero comics from the local settings of inner city life (where characters like Superman and Batman traditionally fought urban crime) to a vast range of global and intergalactic locales where superheroes met unexpected allies and fellow travelers, encountered conflicts on distant worlds that echoed the internecine struggles of warring humans, and found ways of finding common cause with people unlike them.

In other words, comics in this period became visually more bombastic, colorful, and expansive in their scope, depicting superheroes traveling the world and the far reaches of space, uncharted civilizations, and even the infinitesimal world of molecules and atoms.

Simultaneously, comics in this period became more responsive to a new generation of young readers who were being influenced by the New Left, the counterculture, and the Civil Rights movements. These readers were savvy teenagers and young adults who sought out the pleasures of comic book fantasy both to be entertained and to see their burgeoning political values modeled and explored in their favorite imaginative stories. Through published letters to the editor, fan clubs, and comic book conventions, readers found new ways to communicate their values and aspirations to creators who engaged with, incorporated, and sometimes productively disagreed with readers’ worldviews. Ultimately, this meant that 1960s and 1970s superhero comics were the product of complex negotiations between creators and readers, rather than merely the creative invention of a single author or creative team.

You discuss the political project of postwar superhero comics as a kind of “world-making.” What do you mean by world-making and how does this concept help us to understand the ways that such comic books might contribute to fostering public discussions around core issues of their times?

I use the term “world-making” to describe acts of creative innovation—including the imaginative invention of fictional characters and stories, and the development of new aesthetic techniques—that facilitate the formation of social bonds, networks, or interactions in the everyday world. In this way, I see world-making as the site where creative or imaginative labor comes into contact with the work of forging solidarities, affinities, and connections in the social realm.

I borrow the term from the fields of science fiction studies and queer theory: in science fiction studies, world-making (often used interchangeably with the term world-building) is understood as the creative work that goes into forming a fully functioning, internally coherent fictional world with its own rules, values, logics, and flow. In this understanding, world-making is a kind of loving attention to the richness, detail, and complexity of a social system that one has imagined into being.

In queer theory, a variety of thinkers like José Muñoz, Lauren Berlant, and Michael Warner, have used world-making to describe the creative and gutsy ways that sexual minorities have invented cultural practices—from drag performance, to camp, to underground sex cultures, to artists’ salons—that allow them to find community and belonging within a larger dominant culture that denigrates and despises them. In this sense, world-making is understood as involving strategies of social survival that allow one to flourish among others who similarly do not fit into the prescribed logics of a homophobic, sexist, and racist society.

In The New Mutants, I deploy world-making in such a way as to link these two senses of the term. I seek to gain leverage on the ways that the creative development of fictional fantasy worlds can contribute to the production of everyday intimate bonds that produce spaces of social possibility for marginalized and outcast people.

This understanding of world-making helps us grasp how superhero comic books of the 1960s and after produced expansive creative worlds (or fictional “universes”) populated by misfit and outcast characters who’s exploits galvanized a generation of readers to forge substantive social investments in the content of comics and their collective reading practices. Superhero comics readers in this period had the opportunity to write to creators (and potentially have their letters published in monthly letters columns appearing at the end of individual issues), respond to one another’s published letters, convene in fan clubs, collaboratively produce fan zines discussing their viewpoints and investments in various series and characters, and potentially join the comic book writing and drawing community.

The creative worlds that comic book companies like Marvel and DC produced in the 1960s then, actively helped forge a social network devoted to exploring the cultural and political ramifications of the stories they were telling; readers of these stories often thought of themselves as outsiders or maladjusts to the norms of American society, not only in their sense of being fans of a denigrated popular media like comics, but also for some, in their attachment to the egalitarian and democratic ideals espoused by so many of their favorite comics. World-making accurately describes this phenomenon and allows us to gain a better understanding of the ways that fictional or fantasy storytelling shapes social life.

Ramzi Fawaz is Assistant Professor of English and Affiliate Faculty in the Department of Women's, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at UW Madison. His first book, The New Mutants: Superheroes and the Radical Imagination of American Comics won the Center for Lesbian and Gay Studies Fellowship Award for best first book in LGBT Studies.