Damanhur

I suspect this "eco-society" in the mountains of Northern Italy will be unknown to most of my readers, but it created a certain amount of "alarm" and "concern" for some of the Italians involved in planning other stages of the trip. Domahur is an alternative society, founded on environmental and spiritual principles, in the 1975. Unlike many of the other "utopian" communities of that era, it still survives, even thrives, despite a reputation for secrecy and some public misperceptions which link it to "demon worship," a charge which carries weight in a culture that is so deeply rooted in Catholicism. I was invited to visit Damanhur by Betsy Pool, a veteran of the American media industries, who came to this community several years ago with her husband and her daughter. Pool has been asked by the community to help tell their story to the world, and she has increasingly been drawn into current discussions around games-based learning and transmedia storytelling, reaching out to a number of key thinkers in this space, and inviting them to visit Northern Italy and explore possible collaborations.

The first thing we felt when we arrived in Damanhur was an enormous sense of community: much about this society is co-operative. Many, though not all, of the residents live in group arrangements and give a certain amount of time and work each week to the betterment of their community. As you walk through the community, you can see and feel how deeply these people care about each other's well-being, how connected they are to each other's lives, and how much they believe in what they are doing. Everywhere you look, you see signs of the community's commitment to a kind of participatory culture, one where each person is encouraged to be creative and share what they create with the people they care about. We saw paintings, sculpture, architecture, fashion, food, gardening, and farming, all treated as artistic endeavors. We certainly saw signs of people who were still learning how to create and trying their hands at crafts which were unfamiliar to them, but at the same time, we were impressed by the overall high quality of accomplishment the Damahurians had achieved in their respective crafts. At the same time, there was a commitment to protecting the environment, which has led the group to experiment with advanced techniques that allow them to create a more sustainable lifestyle.

This commitment to creativity is perhaps most fully expressed through the religious life of this community. We were taken on a tour of the Temples of Humankind. The Temples are a remarkable accomplishment -- more than 8,500 cubic meters on five different levels, linked by hundreds of meters of corridors, all carved out of the inside of a mountain. On first entering this space, you are overwhelmed by its scale, by the incredible attention to detail, by the craftsmanship, and by the colors and textures which constitute this built environment.

As the guides showed us this space, I was impressed by how deeply they have thought through the core elements of their belief system.

In many ways, this is perhaps the fullest realization I've seen yet of what Joseph Campbell once called Creative Mythology. You get some taste of what it's like to visit the Temple when you watch this video we found on YouTube.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SNWQFNGtHdw

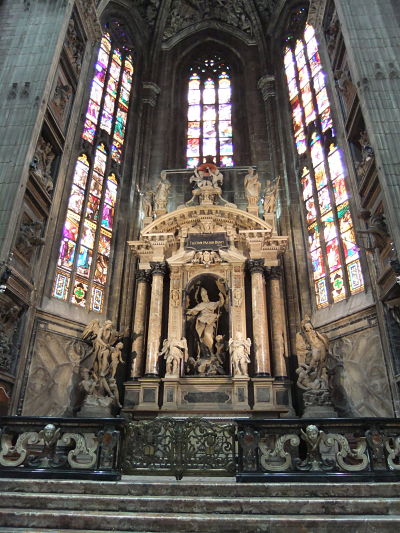

One room in the Temple, the Labryrinth, is devoted to what they see as the many faces of God, with stain glass windows paying their respects to Hades, Aphrodite, Amaterasu, Anahita, Arvisura, Anubis, Astarte, Athena, Balder, Baster, Brahma, Bran, Brigit, Buddha, Christ, Cybel, Enlil, Ganesh, Gaia, Judaism, Horus, Huhuetecotl, Islam, Manitou, Marduk, Mithra, Osiris, Pele, Persephone, Poseidon, Pan, Ra, Sin, Tengri, Thoth, and Unkulu Unkulu, that is, Gods from many corners of the Earth and from many different historic civilizations.

At the same time, there are attempts to incorporate the lived experiences and shared memories of the local people into this larger representation of their belief system, so that the residents create their own self-representations, through a range of media, and place them inside the shared spiritual space. The personal and collective stories of the community, especially the faces of its founding members, are woven into the stain glass windows and murals, suggesting the links between their lives and core values or beliefs of the Damanhuran people.

On a personal level, I was delighted to find the dandelion as an important artistic motif running through the Temple's design: the dandelion also functions as a core metaphor in Spreadable Media, and it was around this same time we were working with NYU to develop a cover design which features the Dandilion as a model for dispersion and circulation.

The Damahurans embrace what they call "estoricism," a particular understanding of the spiritual world, which I find difficult to explain, even though they were generous in seeking to explain its core beliefs to us and answering our many questions. They feel strong connections, for example, with the people of Atlantis, and many of the motifs in their art take inspiration from those bonds. We attended, for example, a shared ritual where members of the community gather each month to consult the Oracles, amongst dancing and drum-beating. I am tempted to say that I am too much a rationalist to share their beliefs, though I value the creative processes through which they seek to share their insights with the world. Yet, they would not see these beliefs as "anti-rationalist," often using terms like "science" to describe their "research" into the metaphysical realm, and they claim to have developed "technologies" which allow them to communicate with other times and with the plant world.

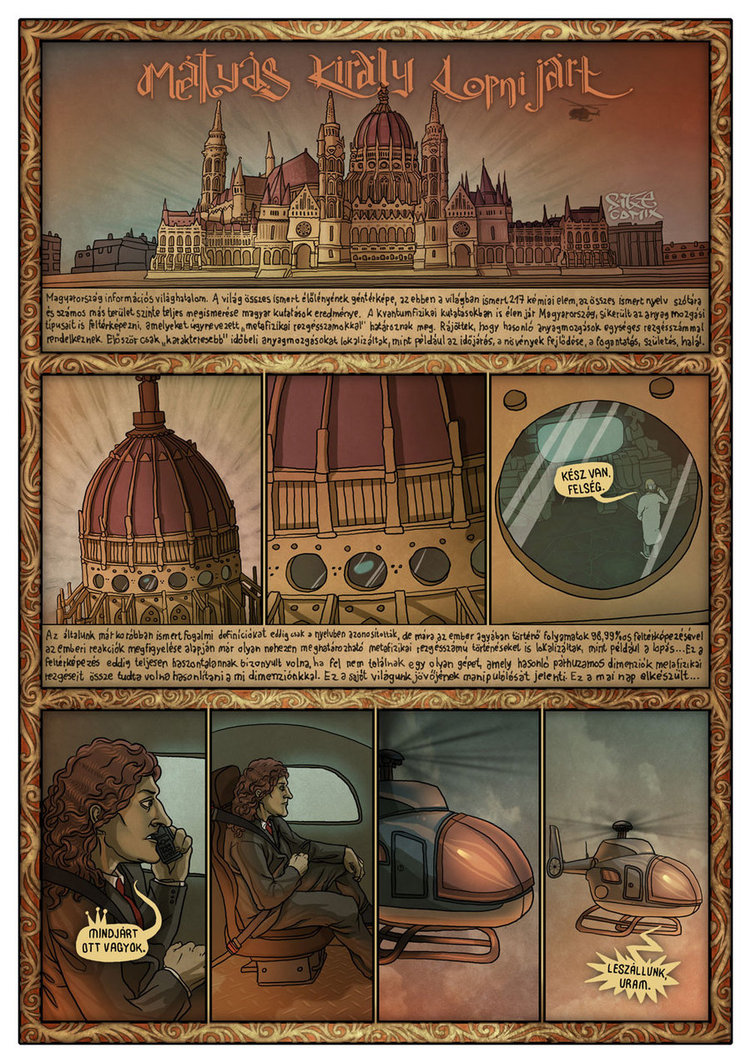

These beliefs, some of which are ancient in origin, co-exist easily with a pretty open attitude towards contemporary technologies. It is not a closed community: people come and go freely, and there were plenty of examples of outside media throughout the living spaces of the homes which I visited. Young people often leave the community to explore the outside world and many return, choosing to live here. Despite some reputation for secrecy, Damanhur is not an enclave, but rather the community's homes, public buildings, and farms intermingle with other local residents who do not share their beliefs. Betsy and her fellow community members are quite knowledgeable about current developments in digital media theory and they are committed to using state of the art techniques to share their narratives with the world. Indeed, any effort to create Damahuran transmedia experiences will build on the foundation of other public outreach projects, which have included picture books and graphic novels seeking to explain their understanding of the universe.

Many of the core texts that have defined transmedia -- from The Matrix and Star Wars to Lost -- have had mythological themes, have drawn their core plot structures from Joseph Campbell, and many of them have tapped into strands of "esoteric" philosophy, so perhaps the world is ready for a transmedia franchise which presents the Damanhurian mythology and which helps us to embrace some of the core values -- creativity, religious tolerance, diversity, community, and concern for the natural world -- which are part of a way of living here.

It was an amazing experience to spend my birthday in Damanhur, learning more about this remarkable culture, and getting to know some of the community members. Betsy and her family were nice enough to prepare a birthday dinner for me, including a traditional Italian cake, which consisted more or less entirely of icing.

Turin

The following day, Peppino Ortoleva, a distinguished Italian media scholar, took us on a walking tour of Turin and shared a delightful lunch with us talking about the state of research on popular culture in Italy. For me, the highlight of this tour was a visit to Il Museo Nazionale del Cinema, the national museum of cinema, whose displays about early and silent cinema Ortoleva has helped to curate . Among the collection's more spectacular holdings is the statue of Moloch, created for the 1914 Giovanni Pastrone epic, Cabiria, which was considered to have been a primary influence on D.W. Griffith's Intolerance and which established Italy as a major creative force in the silent film era.

In Los Angeles, they have recently built a shopping mall which lovingly recreates the giant elephants from Intolerance, but here, in Turin, they have preserved the original statue which was so central to the film's iconography.

The museum does not simply present artifacts from world film history, with a strong focus on the accomplishments of Italian cinema, but it also seeks to interpret the experience of film genres and film going into a series of evocative environments -- ranging from a Western saloon to a mad scientist's laboratory.

The museum becomes a totally immersive environment that provokes strong emotional responses in visitors, very different from the contemplative distance we associate with more traditional museums. One certainly comes away with a deeper appreciation of film history, but the lesson is delivered with such showmanship that this has instantly become one of my favorite museums.

The museum becomes a totally immersive environment that provokes strong emotional responses in visitors, very different from the contemplative distance we associate with more traditional museums. One certainly comes away with a deeper appreciation of film history, but the lesson is delivered with such showmanship that this has instantly become one of my favorite museums.

Afterwards, I shared a public lecture at the Circolo die Lettori about new media literacies and the value of play in educational practice, which seemed to be heavily attended by area teachers. My respondents included Peppino Juan Carlos De Martin (computer science professor at Politecnico engineering school and a commentator on web/computer subjects in national newspaper La Stampa, based in Torino), and Aldo Grasso (TV critic of II courier, Italy’s main newspaper, who teaches media at Catholic University in Milan).

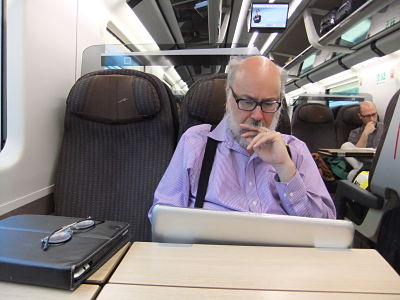

And then we raced to catch a train which took us to Milan. Here, Cynthia caught an image of me, true to form, working on the train.

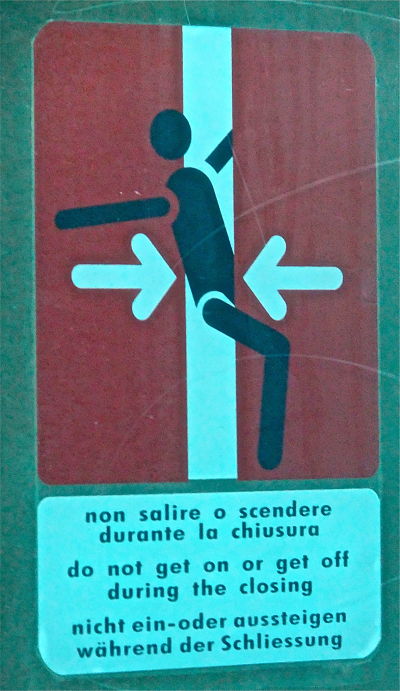

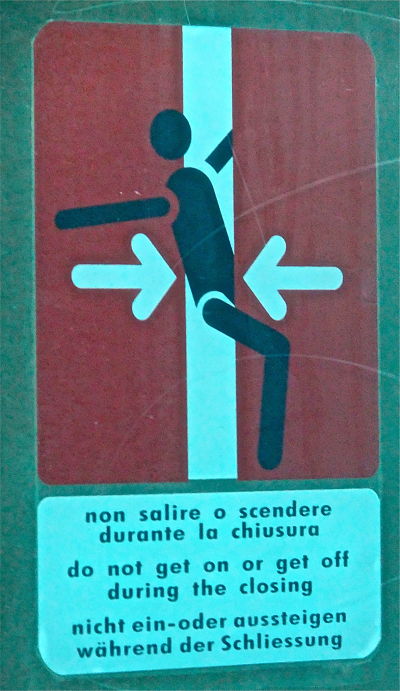

And from that same train trip, here's another entry in my series focused on the Slapstick imagery found on European warning signs.

Gotta hurt!

Milan

In Milan, I gave three public lectures in two days:

First, I spoke to the Italian Scientific Society on Media Education’s national conference. What made this talk especially memorable was that they had brought in a class of local high school students who seemed especially engaged by my discussion of new media and education. At one point, I asked the audience who knew about Invisible Children's Kony 2012 video: all of the students shot their hands instantly, while a surprisingly few of the adults in the audience raised theirs. The young people seemed very proud to be more connected to what was happening in the world than their teachers had been, and I had a wonderful time talking with the students afterwords. They had even brought a video production team to interview me for their school newscast, suggesting that the school was finding good ways to integrate their media literacy skills into the classroom activities.

Second, I spoke to graduate students and industry professionals at Bocconi University, an event organized by the U.S. Embassy in Milan, and hosted by Paola Dubini.

Third, I was one of the invited speakers at Media City: New Spaces, New Aesthetics, an international seminar promoted by Triennale di Milano and curated by Francesco Casetti. The event sought to balance excitement about the ways that new media has enhanced our experiences of living in urban environments ("media makes cities easier to inhabit, more beautiful to see, more intense to share, and more complex to understand") with some skepticism about the ways that smart cites "respond to new needs when they provide a system of surveillance or when they inspect our bodies or when they grant control from distance." Most of the other speakers I heard took this more critical perspective, discussing new forms of "boredom" which emerged as people were subjected to public media which over-rode their ability to enjoy private contemplation or interpersonal conversation as they traveled through public spaces, such as train stations or described in pretty negative terms what happens when the public sought to reclaim spaces of shared celebration in areas controlled and dominated by commercial interests.

My own talk, "From 'Bowling Alone' to 'The New Urban Mechanics': Redesigning the Civic Ecology," took a somewhat more optimistic perspective, describing a range of different models of civic participation and engagement reflected in recent experiments in civic media developed through the Annenberg Innovation Lab, MIT's Center for Civic Media, and the City of Boston's Office for New Urban Mechanics. I organized the projects in terms of data aggregation, information exchange, civic engagement, and collective deliberation. My abstract sums up the key idea: "As we move to think about the future of the city as the locus of a new civic ecology, there has been a tendency to concentrate on notions of information access and transmission to the exclusion of attention to the affective and ritual dimensions of connectivity and mobility.....He examines the ways information technologies may not only support the public sphere but may also offer us a way to reclaim the roles played by the coffee house, the bowling alley, the town pagent, or the carnival, all previous rituals and locations as much or more invested in creating strong social ties as they were to ensuring rational and informed discourse." The following videos showcase some of the projects I identified across my rather rapid tour of current experiments in civic media.

Projects from The Annenberg School of Communications and Journalism

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Sw1DabyLJAs&feature=player_embedded

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8QSYp0dUxx8&feature=player_embedded

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V0dpDw7SJFU&feature=player_embedded

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lUT-cVpevGE&feature=player_embedded

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vL5utjMK8Us&feature=player_embedded

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mn29ZCarhd8&feature=player_embedded

Projects from the MIT Center for Civic Media

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lh_uhaGnqW4&feature=player_embedded

Here's another project developed by Audubon Dougherty, a former Comparative Media Studies student.

Afterwards, Cynthia and I had dinner with Will Straw (McGill University), who has been doing some work on the construction of popular memory online, which has informed some of my recent writings. So, we had a great conversation about zines, obscure forms of print culture, and collecting, all topics I hope to be spending more time thinking about as I get deeper into my new Comics project.

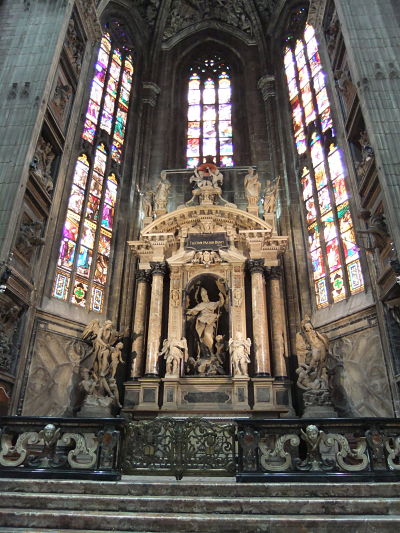

While I was spending my days giving talks, meeting with academics, and giving interviews, Cynthia had a chance to explore Milan. For example, her sightseeing took her to The Duomo, the great 14th century Cathedral, which has been described as the "heart" of this great renaissance city.

Here, you see a detail from the 1562 statue of St. Bartholomew Martyr, which is noted for its depiction of a man who was completely flayed alive, and carries his skin around draped over his shoulder . This sculpture's fascination with muscular and bone structure suggests the role the biological sciences was starting to play in the creative imagination of this period.

Here, we see a monument at the Palazzo Marino erected in the 19th century to honor Leonardo Da Vinci, who did many of his greatest artworks in Milan. The Palazzo is near the Scala, Milan's historic opera house, another key stop on Cynthia's tour.

That evening, Cynthia took me back out to walk at dusk along the outskirts of the Sforza Castle. The Castle/Fort was constructed in the 15th and 16th century during a period when Milan was under Spanish domination. By this point in the trip, Cynthia and I were both deep into reading George R. R. Martin's Game of Thrones series, and thus, we were really fascinating with the heraldic trappings here.

As you can see, this particular castle embraced the image of the snake as central to its identity (again, allowing us to make certain fannish connections with the House of Slytherin in the Harry Potter novels).

It can be hard to make the snake an heroic or even a menacing figure, given all of the negative connotations that often surround reptiles in western culture, but somehow, the castle did a pretty good job of pulling it off.

And Cynthia fell for some stray cats who made their home amidst the ruins and rubble of the castle.

It had to happen. We had been joking the whole trip that we were keeping a "Rock Star" schedule. People had suggested that we print up t-shirts to sell at my talks listing the full route of the tour. I had been comparing notes with my friend, MC Lars, who was doing an honest-to-goodness rock (well, nerd core) tour of Europe over this same period. And every stop along the way, we kept noticing that Bruce Springstein had either just given or was just about to give a concert. Well, we ended up in the same city, Milan, at the same time, but Bruce didn't call me.

VENICE

Venice is exotic, beautiful, romantic, historical, and above all, wet.

We arrived by train from Milan and immediately had to take a water taxi to get to our hotel. I had passed through Venice on the way to the Pordonone Film Festival almost two decades ago and had been scheming to get back ever since; this was Cynthia's first trip, and I think we both became immediate fans of the city, its history, its culture, and its waterways.

For me, a key pilgrimage for this trip was to see the Bridge of Sighs. Historically, the bridge connected the Palace of the Doge's Palace with the prison, so convicted prisoners would cross the bridge and catch their last glimpse of the world outside before being shoved into a dark, dank hole for many years to come. Lord Byron gave the bridge its name and along with it, bestowed a kind of romantic aura around this space. The bridge figures prominently for example in George Roy Hill's A Little Romance, a personal favorite of mine, where two young lovers runaway from their parents in Paris and make their way to Venice where they want above all to cement their romance by kissing underneath the Bridge of Sighs at twilight. So, here, you see me standing in front of the Bridge of Sighs.

And this photograph is taken on the Bridge looking out at the canals below, more or less what the prisoners might have glimpsed as they crossed.

Leave the myth of the Bridge of Sighs aside, the Dodge's Palace represents one of the most epic spaces I have ever visited. It does seem to be full of people who have fallen out of their clothing at the most inappropriate or awkward moments. We had fun imagining the flirtation which might be taking place between the male and female statues who have stood and looked each other across the courtyard for many centuries now.

Inside the palace, outside the men's room, we also saw what was perhaps my favorite example of slapstick signage on the entire trip. Sorry for an image which may be NSFW but it is also hanging in a very public space at the Castle.

There's no attempt here to use euphemisms to explain the functions of this room, which should be clear to anyone in any language. But, I can't help but think that the rush this guy is experiencing is a bit life-threatening in its intensity, which is why it seems to me that this sign belongs alongside the other warning signs I've been featuring here.

While sitting in a cafe near St. Mark's Basilica, we observed a grand procession of priests and worshippers, full of pomp and circumstance.

For Cynthia, who has trained as a glassblower, a key pilgrimage was to the Island of Morino, which for many centuries, has been home of the some of the greatest glass-makers in the world. While glass-blowers from all over come to Morino in hopes of learning more about their crafts, the island's secrets are fiercely protected. It was not hard to find examples here of fine craftsmanship, though it was also not hard to find lots and lots of cheap knockoffs, aimed at the growing herds of tourists who are finding their way to the Island.

I was intrigued to see these figurines of Charlie Chaplin and Jackie Coogan from The Kid (1921). I knew, of course, that Chaplin had left a strong cultural influence on Europe, but I was consistently surprised at how often we encountered Chaplin iconography as we moved across the continent. And more often than not, it was this film, more than Modern Times or City Lights, which was being evoked, suggesting something about the European understanding of the Little Tramp.

Venice was a great city to people-watch, and here are two wonderful images which Cynthia captured of children at play.

I've shared several times through this blog some of the great candy shops we encountered in Europe. What can I say! I have a major sweet tooth. One shop in Venice had turned the sculpting and paint of marzipan into an art form and we had to buy one of the little fish you see in this image to take home and enjoy in our hotel room.

I've shared several times through this blog some of the great candy shops we encountered in Europe. What can I say! I have a major sweet tooth. One shop in Venice had turned the sculpting and paint of marzipan into an art form and we had to buy one of the little fish you see in this image to take home and enjoy in our hotel room.

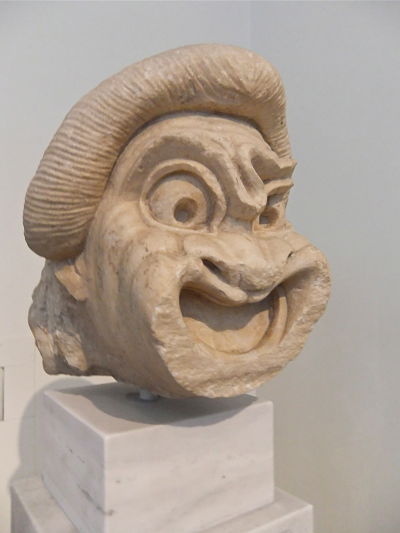

And of course, Venice is strongly associated in the public imagination with carnival, especially with the elaborately decorated masks which people wear to the festivities.

If these images seem a bit random, it is in part because we took Venice easy. We wandered around the streets, looking in windows, watching boats on the canals, sampling local food, drinking wine, and sleeping late. After the intense speaking schedule of the previous few weeks, it was great to have some time to re-energize.

LUCERNE

From Venice, we flew to Zurich, Switzerland, and then, took a train to Lucerne, where I would be speaking at a conference focusing on Social Media and Participatory Storytelling. The event, which included artists, intellectuals, and industry people, was organized, in part, by Kurt Reinhard, whose documentary series on the Future of Storytelling was spotlighted on my blog a few years ago. The conference has set up a Vimeo channel which showcases the proceedings. My talk featured here was the only one presented in English. Lucerne is in the German-speaking region of Switzerland.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jNzVnDJbPGQ

Interestingly, as we got ready to travel to the talk, I spotted some Kony 2012 graffiti spray painted at the base of a distinctly Swiss fountain, an interesting signpost given how often that campaign surfaced in my talks across Europe.

The conference was held in the basement of the building which housed the Bourbaki Panorama. Created in the 19th century, the panorama is a 360 degree painting which depicts an incident during the Franco- Prussian War of 1870-71, where the defeated French General Charles Denis Bourbaki sought refuge in Switzerland and was greeted warmly by the ever-neutral but ever welcoming Swiss people. This incident gave rise to the modern Red Cross. Visitors stand in the center of the painting, which extends via sculpture into the physical space. Such panoramas were a widespread phenomenon in the 19th century all over the world. I grew up visiting the Cyclorama in Atlanta which is from about this same period and depicts the Battle of Atlanta. But, these works have gradually disappeared or been destroyed, so I was happy to get a chance to visit this one. Historically, these paintings might be incorporated into elaborate performance pieces, where plays with light and sound might intensify the drama.

Given a few hours before we needed to head back to the train, we spent some time exploring the waterfront. Those are the Swiss Alps you see in the background.

There was a large bank of swans, more than I had ever seen at one place in my life, who swam the waters and wallowed on the shore. Behind them here, you see the Chapel Bridge, a wooden structure whose origins date back to the 14th century. The Chapel Bridge spans the Reuss, a body of water which eventually contributes to the Rhine in Germany.

This stone lion honors the Swiss mercenaries who served the French royal family and who were massacred during the French revolution.

Coming Soon: Germany, Czech Republic, and Hungary